The Past, Present, and Future of Javascript Where We’Ve Been, Where We Are, and What Lies Ahead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interaction Between Web Browsers and Script Engines

IT 12 058 Examensarbete 45 hp November 2012 Interaction between web browsers and script engines Xiaoyu Zhuang Institutionen för informationsteknologi Department of Information Technology Abstract Interaction between web browser and the script engine Xiaoyu Zhuang Teknisk- naturvetenskaplig fakultet UTH-enheten Web browser plays an important part of internet experience and JavaScript is the most popular programming language as a client side script to build an active and Besöksadress: advance end user experience. The script engine which executes JavaScript needs to Ångströmlaboratoriet Lägerhyddsvägen 1 interact with web browser to get access to its DOM elements and other host objects. Hus 4, Plan 0 Browser from host side needs to initialize the script engine and dispatch script source code to the engine side. Postadress: This thesis studies the interaction between the script engine and its host browser. Box 536 751 21 Uppsala The shell where the engine address to make calls towards outside is called hosting layer. This report mainly discussed what operations could appear in this layer and Telefon: designed testing cases to validate if the browser is robust and reliable regarding 018 – 471 30 03 hosting operations. Telefax: 018 – 471 30 00 Hemsida: http://www.teknat.uu.se/student Handledare: Elena Boris Ämnesgranskare: Justin Pearson Examinator: Lisa Kaati IT 12 058 Tryckt av: Reprocentralen ITC Contents 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................ -

Extending Basic Block Versioning with Typed Object Shapes

Extending Basic Block Versioning with Typed Object Shapes Maxime Chevalier-Boisvert Marc Feeley DIRO, Universite´ de Montreal,´ Quebec, Canada DIRO, Universite´ de Montreal,´ Quebec, Canada [email protected] [email protected] Categories and Subject Descriptors D.3.4 [Programming Lan- Basic Block Versioning (BBV) [7] is a Just-In-Time (JIT) com- guages]: Processors—compilers, optimization, code generation, pilation strategy which allows rapid and effective generation of run-time environments type-specialized machine code without a separate type analy- sis pass or complex speculative optimization and deoptimization Keywords Just-In-Time Compilation, Dynamic Language, Opti- strategies (Section 2.4). However, BBV, as previously introduced, mization, Object Oriented, JavaScript is inefficient in its handling of object property types. The first contribution of this paper is the extension of BBV with Abstract typed object shapes (Section 3.1), object descriptors which encode type information about object properties. Type meta-information Typical JavaScript (JS) programs feature a large number of object associated with object properties then becomes available at prop- property accesses. Hence, fast property reads and writes are cru- erty reads. This allows eliminating run-time type tests dependent on cial for good performance. Unfortunately, many (often redundant) object property accesses. The target of method calls is also known dynamic checks are implied in each property access and the seman- in most cases. tic complexity of JS makes it difficult to optimize away these tests The second contribution of this paper is a further extension through program analysis. of BBV with shape propagation (Section 3.3), the propagation We introduce two techniques to effectively eliminate a large and specialization of code based on object shapes. -

Machine Learning in the Browser

Machine Learning in the Browser The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:38811507 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Machine Learning in the Browser a thesis presented by Tomas Reimers to The Department of Computer Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the subject of Computer Science Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts March 2017 Contents 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Background . .3 1.2 Motivation . .4 1.2.1 Privacy . .4 1.2.2 Unavailable Server . .4 1.2.3 Simple, Self-Contained Demos . .5 1.3 Challenges . .5 1.3.1 Performance . .5 1.3.2 Poor Generality . .7 1.3.3 Manual Implementation in JavaScript . .7 2 The TensorFlow Architecture 7 2.1 TensorFlow's API . .7 2.2 TensorFlow's Implementation . .9 2.3 Portability . .9 3 Compiling TensorFlow into JavaScript 10 3.1 Motivation to Compile . 10 3.2 Background on Emscripten . 10 3.2.1 Build Process . 12 3.2.2 Dependencies . 12 3.2.3 Bitness Assumptions . 13 3.2.4 Concurrency Model . 13 3.3 Experiences . 14 4 Results 15 4.1 Benchmarks . 15 4.2 Library Size . 16 4.3 WebAssembly . 17 5 Developer Experience 17 5.1 Universal Graph Runner . -

Lightweight Django USING REST, WEBSOCKETS & BACKBONE

Lightweight Django USING REST, WEBSOCKETS & BACKBONE Julia Elman & Mark Lavin Lightweight Django LightweightDjango How can you take advantage of the Django framework to integrate complex “A great resource for client-side interactions and real-time features into your web applications? going beyond traditional Through a series of rapid application development projects, this hands-on book shows experienced Django developers how to include REST APIs, apps and learning how WebSockets, and client-side MVC frameworks such as Backbone.js into Django can power the new or existing projects. backend of single-page Learn how to make the most of Django’s decoupled design by choosing web applications.” the components you need to build the lightweight applications you want. —Aymeric Augustin Once you finish this book, you’ll know how to build single-page applications Django core developer, CTO, oscaro.com that respond to interactions in real time. If you’re familiar with Python and JavaScript, you’re good to go. “Such a good idea—I think this will lower the barrier ■ Learn a lightweight approach for starting a new Django project of entry for developers ■ Break reusable applications into smaller services that even more… the more communicate with one another I read, the more excited ■ Create a static, rapid prototyping site as a scaffold for websites and applications I am!” —Barbara Shaurette ■ Build a REST API with django-rest-framework Python Developer, Cox Media Group ■ Learn how to use Django with the Backbone.js MVC framework ■ Create a single-page web application on top of your REST API Lightweight ■ Integrate real-time features with WebSockets and the Tornado networking library ■ Use the book’s code-driven examples in your own projects Julia Elman, a frontend developer and tech education advocate, started learning Django in 2008 while working at World Online. -

Defensive Javascript Building and Verifying Secure Web Components

Defensive JavaScript Building and Verifying Secure Web Components Karthikeyan Bhargavan1, Antoine Delignat-Lavaud1, and Sergio Maffeis2 1 INRIA Paris-Rocquencourt, France 2 Imperial College London, UK Abstract. Defensive JavaScript (DJS) is a typed subset of JavaScript that guarantees that the functional behavior of a program cannot be tampered with even if it is loaded by and executed within a malicious environment under the control of the attacker. As such, DJS is ideal for writing JavaScript security components, such as bookmarklets, single sign-on widgets, and cryptographic libraries, that may be loaded within untrusted web pages alongside unknown scripts from arbitrary third par- ties. We present a tutorial of the DJS language along with motivations for its design. We show how to program security components in DJS, how to verify their defensiveness using the DJS typechecker, and how to analyze their security properties automatically using ProVerif. 1 Introduction Since the advent of asynchronous web applications, popularly called AJAX or Web 2.0, JavaScript has become the predominant programming language for client-side web applications. JavaScript programs are widely deployed as scripts in web pages, but also as small storable snippets called bookmarklets, as down- loadable web apps,1 and as plugins or extensions to popular browsers.2 Main- stream browsers compete with each other in providing convenient APIs and fast JavaScript execution engines. More recently, Javascript is being used to program smartphone and desktop applications3, and also cloud-based server ap- plications,4 so that now programmers can use the same idioms and libraries to write and deploy a variety of client- and server-side programs. -

Webcl for Hardware-Accelerated Web Applications

WebCL for Hardware-Accelerated Web Applications Won Jeon, Tasneem Brutch, and Simon Gibbs What is WebCL? • WebCL is a JavaScript binding to OpenCL. • WebCL enables significant acceleration of compute-intensive web applications. • WebCL currently being standardized by Khronos. 2 tizen.org Contents • Introduction – Motivation and goals – OpenCL • WebCL – Demos – Programming WebCL – Samsung’s Prototype: implementation & performance • Standardization – Khronos WebCL Working Group – WebCL robustness and security – Standardization status • Conclusion – Summary and Resources 3 tizen.org Motivation • New mobile apps with high compute demands: – augmented reality – video processing – computational photography – 3D games 4 tizen.org Motivation… • GPU offers improved FLOPS and FLOPS/watt as compared to CPU. FLOPS/ GPU watt CPU year 5 tizen.org Motivation… • Web-centric platforms 6 tizen.org OpenCL: Overview • Features – C-based cross-platform programming interface – Kernels: subset of ISO C99 with language extensions – Run-time or build-time compilation of kernels – Well-defined numerical accuracy (IEEE 754 rounding with specified maximum error) – Rich set of built-in functions: cross, dot, sin, cos, pow, log … 7 tizen.org OpenCL: Platform Model • A host is connected to one or more OpenCL devices • OpenCL device – A collection of one or more compute units (~ cores) – A compute unit is composed of one or more processing elements (~ threads) – Processing elements execute code as SIMD or SPMD 8 tizen.org OpenCL: Execution Model • Kernel – Basic unit -

A Trusted Mechanised Javascript Specification

A Trusted Mechanised JavaScript Specification Martin Bodin Arthur Charguéraud Daniele Filaretti Inria & ENS Lyon Inria & LRI, Université Paris Sud, CNRS Imperial College London [email protected] [email protected] d.fi[email protected] Philippa Gardner Sergio Maffeis Daiva Naudžiunien¯ e˙ Imperial College London Imperial College London Imperial College London [email protected] sergio.maff[email protected] [email protected] Alan Schmitt Gareth Smith Inria Imperial College London [email protected] [email protected] Abstract sation was crucial. Client code that works on some of the main JavaScript is the most widely used web language for client-side ap- browsers, and not others, is not useful. The first official standard plications. Whilst the development of JavaScript was initially just appeared in 1997. Now we have ECMAScript 3 (ES3, 1999) and led by implementation, there is now increasing momentum behind ECMAScript 5 (ES5, 2009), supported by all browsers. There is the ECMA standardisation process. The time is ripe for a formal, increasing momentum behind the ECMA standardisation process, mechanised specification of JavaScript, to clarify ambiguities in the with plans for ES6 and 7 well under way. ECMA standards, to serve as a trusted reference for high-level lan- JavaScript is the only language supported natively by all major guage compilation and JavaScript implementations, and to provide web browsers. Programs written for the browser are either writ- a platform for high-assurance proofs of language properties. ten directly in JavaScript, or in other languages which compile to We present JSCert, a formalisation of the current ECMA stan- JavaScript. -

DHTML Effects in HTML Generated from DITA

DHTML Effects in HTML Generated from DITA XML to PDF by RenderX XEP XSL-FO Formatter, visit us at http://www.renderx.com/ 2 | OpenTopic | TOC Contents DHTML Effects in HTML Generated from DITA............................................................3 XML to PDF by RenderX XEP XSL-FO Formatter, visit us at http://www.renderx.com/ OpenTopic | DHTML Effects in HTML Generated from DITA | 3 DHTML Effects in HTML Generated from DITA This topic describes an approach to creating expanding text and other DHTML effects in HTML-based output generated from DITA content. It is common for Help systems to use layering techniques to limit the amount of information presented to the reader. The reader chooses to view the information by clicking on a link. Most layering techniques, including expanding text, dropdown text and popup text, are implemented using Dynamic HTML. Overview The DITA Open Toolkit HTML transformations do not provide for layering effects. However, some changes to the XSL-T files, and the use of outputclassmetadata in the DITA topic content, along with some judicious use of JavaScript and CSS, can deliver these layering effects. Authoring Example In the following example illustrating the technique, a note element is to output as dropdown text, where the note label is used to toggle the display of the note text. The note element is simply marked up with an outputclass distinct attribute value (in this case, hw_expansion). < note outputclass="hw_expansion" type="note">Text of the note</note> Without any modification, the DITA OT will transform the note element to a paragraph element with a CSS class of the outputclass value. -

Onclick Event-Handler

App Dev Stefano Balietti Center for European Social Science Research at Mannheim University (MZES) Alfred-Weber Institute of Economics at Heidelberg University @balietti | stefanobalietti.com | @nodegameorg | nodegame.org Building Digital Skills: 5-14 May 2021, University of Luzern Goals of the Seminar: 1. Writing and understanding asynchronous code: event- listeners, remote functions invocation. 2. Basic front-end development: HTML, JavaScript, CSS, debugging front-end code. 3. Introduction to front-end frameworks: jQuery and Bootstrap 4. Introduction to back-end development: NodeJS Express server, RESTful API, Heroku cloud. Outputs of the Seminar: 1. Web app: in NodeJS/Express. 2. Chrome extensions: architecture and examples. 3. Behavioral experiment/survey: nodeGame framework. 4. Mobile development: hybrid apps with Apache Cordova, intro to Ionic Framework, progressive apps (PWA). Your Instructor: Stefano Balietti http://stefanobalietti.com Currently • Fellow in Sociology Mannheim Center for European Social Research (MZES) • Postdoc at the Alfred Weber Institute of Economics at Heidelberg University Previously o Microsoft Research - Computational Social Science New York City o Postdoc Network Science Institute, Northeastern University o Fellow IQSS, Harvard University o PhD, Postdoc, Computational Social Science, ETH Zurich My Methodology Interface of computer science, sociology, and economics Agent- Social Network Based Analysis Models Machine Learning for Optimal Experimental Experimental Methods Design Building Platforms Patterns -

Introduction to Scalable Vector Graphics

Introduction to Scalable Vector Graphics Presented by developerWorks, your source for great tutorials ibm.com/developerWorks Table of Contents If you're viewing this document online, you can click any of the topics below to link directly to that section. 1. Introduction.............................................................. 2 2. What is SVG?........................................................... 4 3. Basic shapes............................................................ 10 4. Definitions and groups................................................. 16 5. Painting .................................................................. 21 6. Coordinates and transformations.................................... 32 7. Paths ..................................................................... 38 8. Text ....................................................................... 46 9. Animation and interactivity............................................ 51 10. Summary............................................................... 55 Introduction to Scalable Vector Graphics Page 1 of 56 ibm.com/developerWorks Presented by developerWorks, your source for great tutorials Section 1. Introduction Should I take this tutorial? This tutorial assists developers who want to understand the concepts behind Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) in order to build them, either as static documents, or as dynamically generated content. XML experience is not required, but a familiarity with at least one tagging language (such as HTML) will be useful. For basic XML -

Typescript-Handbook.Pdf

This copy of the TypeScript handbook was created on Monday, September 27, 2021 against commit 519269 with TypeScript 4.4. Table of Contents The TypeScript Handbook Your first step to learn TypeScript The Basics Step one in learning TypeScript: The basic types. Everyday Types The language primitives. Understand how TypeScript uses JavaScript knowledge Narrowing to reduce the amount of type syntax in your projects. More on Functions Learn about how Functions work in TypeScript. How TypeScript describes the shapes of JavaScript Object Types objects. An overview of the ways in which you can create more Creating Types from Types types from existing types. Generics Types which take parameters Keyof Type Operator Using the keyof operator in type contexts. Typeof Type Operator Using the typeof operator in type contexts. Indexed Access Types Using Type['a'] syntax to access a subset of a type. Create types which act like if statements in the type Conditional Types system. Mapped Types Generating types by re-using an existing type. Generating mapping types which change properties via Template Literal Types template literal strings. Classes How classes work in TypeScript How JavaScript handles communicating across file Modules boundaries. The TypeScript Handbook About this Handbook Over 20 years after its introduction to the programming community, JavaScript is now one of the most widespread cross-platform languages ever created. Starting as a small scripting language for adding trivial interactivity to webpages, JavaScript has grown to be a language of choice for both frontend and backend applications of every size. While the size, scope, and complexity of programs written in JavaScript has grown exponentially, the ability of the JavaScript language to express the relationships between different units of code has not. -

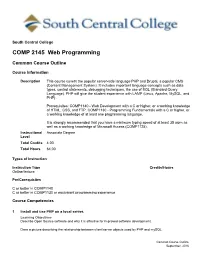

COMP 2145 Web Programming

South Central College COMP 2145 Web Programming Common Course Outline Course Information Description This course covers the popular server-side language PHP and Drupal, a popular CMS (Content Management System). It includes important language concepts such as data types, control statements, debugging techniques, the use of SQL (Standard Query Language). PHP will give the student experience with LAMP (Linux, Apache, MySQL, and PHP) . Prerequisites: COMP1140 - Web Development with a C or higher, or a working knowledge of HTML, CSS, and FTP. COMP1130 - Programming Fundamentals with a C or higher, or a working knowledge of at least one programming language. It is strongly recommended that you have a minimum typing speed of at least 35 wpm as well as a working knowledge of Microsoft Access (COMP1125). Instructional Associate Degree Level Total Credits 4.00 Total Hours 64.00 Types of Instruction Instruction Type Credits/Hours Online/lecture Pre/Corequisites C or better in COMP1140 C or better in COMP1130 or equivalent programming experience Course Competencies 1 Install and use PHP on a local server. Learning Objectives Describe Open Source software and why it is effective for improved software development. Draw a picture describing the relationship between client/server objects used by PHP and mySQL. Common Course Outline September, 2016 Install PHP and mySQL and an Apache web server. Write a simple test program using PHP on the local server (http://localhost/ ) Establish a working environment for PHP web page development. Use variables, constants, and environment variables in a PHP program. 2 Utilize HTML forms and PHP to get information from the user.