EURODOLLARS Marvin Goodfriend

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eurocurrency Contracts

RS - IV-5 Eurocurrency Contracts Futures Contracts, FRAs, & Options Eurocurrency Futures • Eurocurrency time deposit Euro-zzz: The currency of denomination of the zzz instrument is not the official currency of the country where the zzz instrument is traded. Example: Euro-deposit (zzz = a deposit) A Mexican firm deposits USD in a Mexican bank. This deposit qualifies as a Eurodollar deposit. ¶ The interest rate paid on Eurocurrency deposits is called LIBOR. Eurodeposits tend to be short-term: 1 or 7 days; or 1, 3, or 6 months. 1 RS - IV-5 Typical Eurodeposit instruments: Time deposit: Non-negotiable, registered instrument. Certificate of deposit: Negotiable and often bearer. Note I: Eurocurrency deposits are direct obligations of commercial banks accepting the deposits and are not guaranteed by any government. They are low-risk investments, but Eurodollar deposits are not risk-free. Note II: Eurocurrency deposits play a major role in the international capital market. They serve as a benchmark interest rate for corporate funding. • Eurocurrency time deposits are the underlying asset in Eurodollar currency futures. • Eurocurrency futures contract A Eurocurrency futures contract calls for the delivery of a 3-mo Eurocurrency time USD 1M deposit at a given interest rate (LIBOR). Similar to any other futures a trader can go long (a promise to make a future 3-mo deposit) or short (a promise to take a future 3-mo. loan). With Eurocurrency futures, a trader can go: - Long: Assuring a yield for a future USD 1M 3-mo deposit - Short: Assuring a borrowing rate for a future USD 1M 3-mo loan. -

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the Post-Cold War Era

ARTICLES THE EUROPEAN BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT AND THE POST-COLD WAR ERA JoHN LINARELLi* 1. INTRODUCTION The end of the Cold War has brought many new challen- ges to the world. Yet, the post-Cold War era possesses a few characteristics which are strangely reminiscent of times preceding World War II. Prior to World War I1, and before the rise of communism in Central and Eastern Europe, the West was viewed as a potential source of the means for modernization and technological progress.1 Cooperation with the West was an important part of the economic policies of Peter the Great as well as Lenin.2 "Look to the West" policies were also followed in Japan, during the Meiji era, and were attempted by late 19th century Qing dynastic rulers and the Republican government in China.3 The purely political and economic characteristics of the West, * Partner, Braverman & Linarelli; Adjunct Professor, Georgetown University Law Center and the Catholic University Columbus School of Law. I find myself in the habit of thanking Peter Fox, Partner, Mallesons Stephen Jaques and Adjunct Professor, Georgetown University Law Center, for his encouragement and guidance. His insights have proven invaluable. See Kazimierz Grzybowski, The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance and the European Community, 84 AM. J. IN'L L. 284, 284 (1990). 2See id. 3 See James V. Feinerman, Japanese Success, Chinese Failure: Law and Development in the Nineteenth Century (unpublished manuscript, on file with the author). (373) Published by Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository, 2014 374 U. Pa. J. Int'l Bus. L. [Vol. -

Modelling Australian Dollar Volatility at Multiple Horizons with High-Frequency Data

risks Article Modelling Australian Dollar Volatility at Multiple Horizons with High-Frequency Data Long Hai Vo 1,2 and Duc Hong Vo 3,* 1 Economics Department, Business School, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Finance, Banking and Business Administration, Quy Nhon University, Binh Dinh 560000, Vietnam 3 Business and Economics Research Group, Ho Chi Minh City Open University, Ho Chi Minh City 7000, Vietnam * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 July 2020; Accepted: 17 August 2020; Published: 26 August 2020 Abstract: Long-range dependency of the volatility of exchange-rate time series plays a crucial role in the evaluation of exchange-rate risks, in particular for the commodity currencies. The Australian dollar is currently holding the fifth rank in the global top 10 most frequently traded currencies. The popularity of the Aussie dollar among currency traders belongs to the so-called three G’s—Geology, Geography and Government policy. The Australian economy is largely driven by commodities. The strength of the Australian dollar is counter-cyclical relative to other currencies and ties proximately to the geographical, commercial linkage with Asia and the commodity cycle. As such, we consider that the Australian dollar presents strong characteristics of the commodity currency. In this study, we provide an examination of the Australian dollar–US dollar rates. For the period from 18:05, 7th August 2019 to 9:25, 16th September 2019 with a total of 8481 observations, a wavelet-based approach that allows for modelling long-memory characteristics of this currency pair at different trading horizons is used in our analysis. -

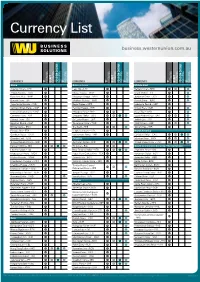

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

U.S. Government Printing Office Style Manual, 2008

U.S. Government Printing Offi ce Style Manual An official guide to the form and style of Federal Government printing 2008 PPreliminary-CD.inddreliminary-CD.indd i 33/4/09/4/09 110:18:040:18:04 AAMM Production and Distribution Notes Th is publication was typeset electronically using Helvetica and Minion Pro typefaces. It was printed using vegetable oil-based ink on recycled paper containing 30% post consumer waste. Th e GPO Style Manual will be distributed to libraries in the Federal Depository Library Program. To fi nd a depository library near you, please go to the Federal depository library directory at http://catalog.gpo.gov/fdlpdir/public.jsp. Th e electronic text of this publication is available for public use free of charge at http://www.gpoaccess.gov/stylemanual/index.html. Use of ISBN Prefi x Th is is the offi cial U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identifi ed to certify its authenticity. ISBN 978–0–16–081813–4 is for U.S. Government Printing Offi ce offi cial editions only. Th e Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Offi ce requests that any re- printed edition be labeled clearly as a copy of the authentic work, and that a new ISBN be assigned. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 978-0-16-081813-4 (CD) II PPreliminary-CD.inddreliminary-CD.indd iiii 33/4/09/4/09 110:18:050:18:05 AAMM THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE STYLE MANUAL IS PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTION AND AUTHORITY OF THE PUBLIC PRINTER OF THE UNITED STATES Robert C. -

History of the International Monetary System and Its Potential Reformulation

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-2010 History of the international monetary system and its potential reformulation Catherine Ardra Karczmarczyk University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Part of the Economic History Commons, Economic Policy Commons, and the Political Economy Commons Recommended Citation Karczmarczyk, Catherine Ardra, "History of the international monetary system and its potential reformulation" (2010). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1341 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. History of the International Monetary System and its Potential Reformulation Catherine A. Karczmarczyk Honors Thesis Project Dr. Anthony Nownes and Dr. Anne Mayhew 02 May 2010 Karczmarczyk 2 HISTORY OF THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY SYSTEM AND ITS POTENTIAL REFORMATION Introduction The year 1252 marked the minting of the very first gold coin in Western Europe since Roman times. Since this landmark, the international monetary system has evolved and transformed itself into the modern system that we use today. The modern system has its roots beginning in the 19th century. In this thesis I explore four main ideas related to this history. First is the evolution of the international monetary system. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

The Eurocurrency Market and the Recycling of Petrodollars

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Supplement to NBER Report Fifteen Volume Author/Editor: Raymond F. Mikesell Volume Publisher: NBER Volume ISBN: Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/mike75-1 Conference Date: Publication Date: October 1975 Chapter Title: The Eurocurrency Market and the Recycling of Petrodollars Chapter Author(s): Raymond F. Mikesell Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c4216 Chapter pages in book: (p. 1 - 7) october 1975 15 NATIONAL BUREAU REPORT supernent The Eurocurrency Market and the Recycling of Petrodollars by RaymondF. Mikesell NationalBureau of Economic Research, Inc., and University of Oregon I.. NATIONAL BUREAU OF. ECONOMIC RESEARCH, INC. NEW YORK; N.Y. 10016 National Bureau Report and supplements thereto have been exempted from the rulesgoverning submissionof manuscriptsto, and critical reviewby, the Board of Directorsof the National Bureau. Each issue, however, is reviewed and accepted for publication by a standing committee of the Board. Copyright©1975 byNational Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America THE EUROCURRENCY MARKET AND THE RECYCLING OF PETRODOLLARS l)y RaymondF. Mikesell National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. and University of Oregon Following the 1973 quadrupling of. oil asset holders throughout the world can ad- prices, the oil producing countries began to just their portfolio holdings in a variety of invest a substantial portion of their sur- currencies without having to deal with for- pluses in the Eurocurrency market. As a eign banks, and the U.S. and foreign resi- result new interest was sparked in the role dents can receive interest on dollar deposits of the Eurocurrency market in international with a maturity of less than thirty days, finance. -

New France (Ca

New France (ca. 1600-1770) Trade silver, beaver, eighteenth century Manufactured in Europe and North America for trade with the Native peoples, trade silver came in many forms, including ear bobs, rings, brooches, gorgets, pendants, and animal shapes. According to Adam Shortt,5 the great France, double tournois, 1610 Canadian economic historian, the first regular Originally valued at 2 deniers, the system of exchange in Canada involving Europeans copper “double tournois” was shipped to New France in large quantities during occurred in Tadoussac in the early seventeenth the early 1600s to meet the colony’s century. Here, French traders bartered each year need for low-denomination coins. with the Montagnais people (also known as the Innu), trading weapons, cloth, food, silver items, and tobacco for animal pelts, especially those of the beaver. Because of the risks associated with In 1608, Samuel de Champlain founded transporting gold and silver (specie) across the the first colonial settlement at Quebec on the Atlantic, and to attract and retain fresh supplies of St. Lawrence River. The one universally accepted coin, coins were given a higher value in the French medium of exchange in the infant colony naturally colonies in Canada than in France. In 1664, became the beaver pelt, although wheat and moose this premium was set at one-eighth but was skins were also employed as legal tender. As the subsequently increased. In 1680, monnoye du pays colony expanded, and its economic and financial was given a value one-third higher than monnoye needs became more complex, coins from France de France, a valuation that held until 1717 when the came to be widely used. -

Foreign Exchange Markets and Exchange Rates

Salvatore c14.tex V2 - 10/18/2012 1:15 P.M. Page 423 Foreign Exchange Markets chapter and Exchange Rates LEARNING GOALS: After reading this chapter, you should be able to: • Understand the meaning and functions of the foreign exchange market • Know what the spot, forward, cross, and effective exchange rates are • Understand the meaning of foreign exchange risks, hedging, speculation, and interest arbitrage 14.1 Introduction The foreign exchange market is the market in which individuals, firms, and banks buy and sell foreign currencies or foreign exchange. The foreign exchange market for any currency—say, the U.S. dollar—is comprised of all the locations (such as London, Paris, Zurich, Frankfurt, Singapore, Hong Kong, Tokyo, and New York) where dollars are bought and sold for other currencies. These different monetary centers are connected electronically and are in constant contact with one another, thus forming a single international foreign exchange market. Section 14.2 examines the functions of foreign exchange markets. Section 14.3 defines foreign exchange rates and arbitrage, and examines the relationship between the exchange rate and the nation’s balance of payments. Section 14.4 defines spot and forward rates and discusses foreign exchange swaps, futures, and options. Section 14.5 then deals with foreign exchange risks, hedging, and spec- ulation. Section 14.6 examines uncovered and covered interest arbitrage, as well as the efficiency of the foreign exchange market. Finally, Section 14.7 deals with the Eurocurrency, Eurobond, and Euronote markets. In the appendix, we derive the formula for the precise calculation of the covered interest arbitrage margin. -

How One Dollar Grew Over Time

MFS ADVISOR EDGESM INVESTING BASICS How One Dollar Grew Over Time mfs.com Stocks — historically, a good place for long-term investors Worldwide Despite the many national and international crises throughout the past 30 years, COVID-19 investing in stocks has kept investors on track in pursuing their long-term goals. pandemic N. Korea STOCK defies $21.11 world with missile testing Oil prices Oil prices War plunge at record to 5-year with Iraq levels 9/11 begins Looming US low Y2K terrorist S&P 500 and “Fiscal Cliff” concerns attacks Hurricanes Dow fall to crisis on US Corporate Katrina and 10-year lows Wilma Dow Asian accounting breaks economic scandals President turmoil US BONDS 5000, $5.53 Bush Soviet market signs Union “too high” CASH NAFTA $2.14 collapses INFLATION $1 $1.95 1/91 1/96 1/01 1/06 1/11 1/16 12/20 Source: SPAR, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Important risk considerations MARKET SEGMENT REPRESENTED BY IMPORTANT RISK CONSIDERATIONS Stocks Standard & Poor’s 500 Stock Index1 Stocks: Common stocks generally provide an opportunity for more capital appreciation than fixed-income investments US Bonds Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index2 but are also subject to greater market fluctuations. US Bonds and Cash: Corporate bonds, US Treasury bills, and US Cash FTSE 3-month Treasury Bill Index3 government bonds fluctuate in value, but if held to maturity, offer a fixed rate of return and a fixed principal value. Inflation Consumer Price Index4 Keep in mind that all investments, including mutual funds, carry a certain amount of risk including the possible loss of the principal amount invested. -

Reforming the International Monetary System: from Roosevelt to Reagan

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 384 560 SO 025 006 AUTHOR Hormats, Robert D. TITLE Reforming the International Monetary System: From Roosevelt to Reagan. Headline Series No. 281. INSTITUTION Foreign Policy Association, New York, N.Y. REPORT NO ISBN-0-87124-113-7; ISSN-0017-8780 PUB DATE Jun 87 NOTE 84p. AVAILABLE FROM Foreign Policy Association, 729 Seventh Avenue, New fork, NY 10019 ($5.95). PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Banking; Economic Change; Economics; *Finance Reform; Financial Policy; Financial Problems; *Foreign Policy; Higher Education; International Cooperation; *International Organizations; International Programs; *International Relations; International Studies; *International Trade; *Monetary Systems; Money Management; Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS *International Monetary Fund; Reagan (Ronald); Roosevelt (Franklin D) ABSTRACT This book examines the changed, and .anging, international monetary system.It describes how the system has evolved under nine Presidents, from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Ronald Reagan. It also discusses the broader evolution of the world economy during this period, including the trade and investment issues to which international monetary policy is closely linked. The subjects are predominantly international but have a major impact on domestic economies. These international effects are why they should be of concern to most people. The dollar is viewed as both a national and an international money. The International Monetary Fund (IMF)is viewed as