Chris Palma on Google Book Search at the Text & Academic Authors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intro to Google for the Hill

Introduction to A company built on search Our mission Google’s mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful. As a first step to fulfilling this mission, Google’s founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin developed a new approach to online search that took root in a Stanford University dorm room and quickly spread to information seekers around the globe. The Google search engine is an easy-to-use, free service that consistently returns relevant results in a fraction of a second. What we do Google is more than a search engine. We also offer Gmail, maps, personal blogging, and web-based word processing products to name just a few. YouTube, the popular online video service, is part of Google as well. Most of Google’s services are free, so how do we make money? Much of Google’s revenue comes through our AdWords advertising program, which allows businesses to place small “sponsored links” alongside our search results. Prices for these ads are set by competitive auctions for every search term where advertisers want their ads to appear. We don’t sell placement in the search results themselves, or allow people to pay for a higher ranking there. In addition, website managers and publishers take advantage of our AdSense advertising program to deliver ads on their sites. This program generates billions of dollars in revenue each year for hundreds of thousands of websites, and is a major source of funding for the free content available across the web. Google also offers enterprise versions of our consumer products for businesses, organizations, and government entities. -

Recaptcha: Human-Based Character Recognition Via Web Security

REPORTS on September 12, 2008 and blogs. For example, CAPTCHAs prevent www.sciencemag.org reCAPTCHA: Human-Based Character ticket scalpers from using computer programs to buy large numbers of concert tickets, only to re Recognition via Web Security Measures sell them at an inflated price. Sites such as Gmail and Yahoo Mail use CAPTCHAs to stop spam Luis von Ahn,* Benjamin Maurer, Colin McMillen, David Abraham, Manuel Blum mers from obtaining millions of free e mail accounts, which they would use to send spam CAPTCHAs (Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart) are e mail. Downloaded from widespread security measures on the World Wide Web that prevent automated programs from According to our estimates, humans around abusing online services. They do so by asking humans to perform a task that computers cannot yet the world type more than 100 million CAPTCHAs perform, such as deciphering distorted characters. Our research explored whether such human every day (see supporting online text), in each case effort can be channeled into a useful purpose: helping to digitize old printed material by asking spending a few seconds typing the distorted char users to decipher scanned words from books that computerized optical character recognition failed acters. In aggregate, this amounts to hundreds of to recognize. We showed that this method can transcribe text with a word accuracy exceeding 99%, thousands of human hours per day. We report on matching the guarantee of professional human transcribers. Our apparatus is deployed in more an experiment that attempts to make positive use than 40,000 Web sites and has transcribed over 440 million words. -

1592213370-Monetize.Pdf

Table of Contents 1. Online Monetization: How to Turn Your Following into Cash 1.1 What is monetization? 1.2 How to monetize your website, blog, or social media channel 1.3 Does a monetization formula exist? Chapter 1 Takeaways 2. How to Monetize Your Blog The Right Way 2.1 Why should you start monetizing with your blog? 2.2 How to earn money from blogging 2.3 How to transform your blog visitors into loyal fans 2.4 Blog monetization tools you should know about Chapter 2 Takeaways 3. Facebook Monetization: The What, Why, Where, and How 3.1 How Facebook monetization works 3.2 Facebook monetization strategies Chapter 3 Takeaways 4. How to monetize your Instagram following 4.1 Before you go chasing that Instagram money... 4.2 The four main ways you can earn money on Instagram 4.3 Instagram monetization tools 4.4 Ideas to make money on Instagram Chapter 4 Takeaways 5. Monetizing a YouTube Brand Without Ads 5.1 How to monetize Youtube videos without Adsense 5.2 Essential Youtube monetization tools 5.3 Factors that determine your channel’s long-term success Chapter 5 Takeaways 1. Online Monetization: How to Turn Your Following into Cash 5 Stop me if you’ve heard this one before. Jenn, a customer service agent at a car leasing company, is fed up with her job. Her pay’s lousy, she’s on edge with customers yelling at her over the phone all day (they actually treat her worse in person), and her boss ignores all her suggestions, even though she knows he could make her job a lot less stressful. -

Google Adsense Fuels Growth for Android- Focused Site

Google AdSense Case Study Google AdSense fuels growth for Android- focused site About elandroidelibre • elandoidelibre.com • Based in Madrid • Blog about the Android operating system “We regard AdSense as an essential tool that’s helping us to set up more blogs, take on more staff, and earn more revenue.” — Paolo Álvarez, administrator and editor. elandroidelibre.com (“the free Android”) is a leading Spanish-language blog about the Android operating system, featuring news, reviews, games and other apps for Android smartphone users. Launched in 2009, it now employs six people and attracts 6.5 million visits each month. Since the outset, Google AdSense has accounted for around 40 per cent of its income. Administrator and editor Paolo Álvarez says: “I was attracted to AdSense because it was simple and effective. I began using it right from the start, and even though I wasn’t an expert, I could see that it worked.” He’s highly satisfied with the quality and relevance of the ads appearing on his site, and says the 300 x 250 Medium Rectangle and the 728 x 90 Leaderboard formats work particularly well. Álvarez uses Google AdSense reports and Google Analytics to analyse the return on the site and gain a better understanding of the kind of visitors it attracts: for example 30 per cent of traffic and income comes from mobile devices. He has also begun using Google’s free ad serving solution, DoubleClick for Publishers, allowing him to manage his online advertising more effectively and segment traffic from different countries. He plans to continue improving the quality and quantity of content in the future. -

Modern Competences on the International Labor Market

Associate Professor Adam Jabło ński Head of Scientific Institute of Management WSB University in Pozna ń, Faculty in Chorzów, POLAND 6th International Week 3rd to 7th June 2019 in Viana do Castelo, Portugal ERASMUS+ training opportunities for students: a gateway to the International Labor Market Adam Jabło ński is an Associate Professor in WSB University in Poznan Faculty in Chorzow, e-mail: [email protected] . He is also President of the Board of a reputable management consulting company “OTTIMA plus” Ltd. of Katowice , and Vice-President of the “Southern Railway Cluster” Association of Katowice , which supports development in railway transport and the transfer of innovation, as well as cooperation with European railway clusters (as a member of the European Railway Clusters Initiative). He holds a postdoctoral degree in Economic Sciences , specializing in Management Science . Having worked as a management consultant since 1997, he has broadened his experience and expertise through co-operation with a number of leading companies in Poland and abroad. Adam Jabło ński is the author of a variety of studies and business analyses on business models, value management, risk management, the balanced scorecard and corporate social responsibility. He has also written and co-written several monographs and over 100 scientific articles in the field of management. Adam’s academic interests focus on the issues of modern and efficient business model design, including Sustainable Business Models and the principles of company value building strategy that includes the rules of Corporate Social Responsibility. Plan of Presentation: 1. Introduction to modern competences on the International Labor Market. -

Broadband Video Advertising 101

BROADBAND VIDEO ADVERTISING 101 The web audience’s eyes are already on broadband THE ADVERTISING CHALLENGES OF video, making the player and the surrounding areas the ONLINE PUBLISHERS perfect real estate for advertising. This paper focuses on what publishers need to know about online advertising in Why put advertising on your broadband video? When order to meet their business goals and adapt as the online video plays on a site, the user’s attention is largely drawn advertising environment shifts. away from other content areas on the page and is focused on the video. The player, therefore, is a premium spot for advertising, and this inventory space commands a premium price. But adding advertising to your online video involves a lot of moving parts and many decisions. You need to consider the following: • What types and placements of ads do you want? • How do you count the ads that are viewed? • How do you ensure that the right ad gets shown to the right viewer? Luckily, there are many vendors that can help publishers fill up inventory, manage their campaigns, and get as much revenue from their real estate as possible. This paper focuses on the online advertising needs of the publisher and the services that can help them meet their advertising goals. THE VIDEO PLATFORM COMCASTTECHNOLOGYSOLUTIONS.COM | 800.844.1776 | © 2017 COMCAST TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS ONLINE VIDEO ADS: THE BASICS AD TYPES You have many choices in how you combine ads with your content. The best ads are whatever engages your consumers, keeps them on your site, and makes them click. -

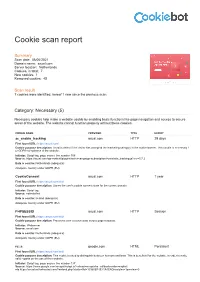

Cookie Scan Report

Cookie scan report Summary Scan date: 08/06/2021 Domain name: axual.com Server location: Netherlands Cookies, in total: 7 New cookies: 1 Removed cookies: 45 Scan result 7 cookies were identified, hereof 1 new since the previous scan. Category: Necessary (5) Necessary cookies help make a website usable by enabling basic functions like page navigation and access to secure areas of the website. The website cannot function properly without these cookies. COOKIE NAME PROVIDER TYPE EXPIRY ac_enable_tracking axual.com HTTP 29 days First found URL: https://axual.com/ Cookie purpose description: Used to detect if the visitor has accepted the marketing category in the cookie banner. This cookie is necessary f or GDPR-compliance of the website. Initiator: Script tag, page source line number 508 Source: https://axual.com/wp-content/plugins/activecampaign-subscription-forms/site_tracking.js?ver=5.7.2 Data is sent to: Netherlands (adequate) Adequate country under GDPR (EU) CookieConsent axual.com HTTP 1 year First found URL: https://axual.com/trial/ Cookie purpose description: Stores the user's cookie consent state for the current domain Initiator: Script tag Source: notinstalled Data is sent to: Ireland (adequate) Adequate country under GDPR (EU) PHPSESSID axual.com HTTP Session First found URL: https://axual.com/trial/ Cookie purpose description: Preserves user session state across page requests. Initiator: Webserver Source: axual.com Data is sent to: Netherlands (adequate) Adequate country under GDPR (EU) rc::a google.com HTML Persistent First found URL: https://axual.com/trial/ Cookie purpose description: This cookie is used to distinguish between humans and bots. -

Artificial Intelligence, Big Data and Cloud Computing 144

Digital Business and Electronic Digital Business Models StrategyCommerceProcess Instruments Strategy, Business Models and Technology Lecture Material Lecture Material Prof. Dr. Bernd W. Wirtz Chair for Information & Communication Management German University of Administrative Sciences Speyer Freiherr-vom-Stein-Straße 2 DE - 67346 Speyer- Email: [email protected] Prof. Dr. Bernd W. Wirtz Chair for Information & Communication Management German University of Administrative Sciences Speyer Freiherr-vom-Stein-Straße 2 DE - 67346 Speyer- Email: [email protected] © Bernd W. Wirtz | Digital Business and Electronic Commerce | May 2021 – Page 1 Table of Contents I Page Part I - Introduction 4 Chapter 1: Foundations of Digital Business 5 Chapter 2: Mobile Business 29 Chapter 3: Social Media Business 46 Chapter 4: Digital Government 68 Part II – Technology, Digital Markets and Digital Business Models 96 Chapter 5: Digital Business Technology and Regulation 97 Chapter 6: Internet of Things 127 Chapter 7: Artificial Intelligence, Big Data and Cloud Computing 144 Chapter 8: Digital Platforms, Sharing Economy and Crowd Strategies 170 Chapter 9: Digital Ecosystem, Disintermediation and Disruption 184 Chapter 10: Digital B2C Business Models 197 © Bernd W. Wirtz | Digital Business and Electronic Commerce | May 2021 – Page 2 Table of Contents II Page Chapter 11: Digital B2B Business Models 224 Part III – Digital Strategy, Digital Organization and E-commerce 239 Chapter 12: Digital Business Strategy 241 Chapter 13: Digital Transformation and Digital Organization 277 Chapter 14: Digital Marketing and Electronic Commerce 296 Chapter 15: Digital Procurement 342 Chapter 16: Digital Business Implementation 368 Part IV – Digital Case Studies 376 Chapter 17: Google/Alphabet Case Study 377 Chapter 18: Selected Digital Case Studies 392 Chapter 19: The Digital Future: A Brief Outlook 405 © Bernd W. -

Ei-Report-2013.Pdf

Economic Impact United States 2013 Stavroulla Kokkinis, Athina Kohilas, Stella Koukides, Andrea Ploutis, Co-owners The Lucky Knot Alexandria,1 Virginia The web is working for American businesses. And Google is helping. Google’s mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful. Making it easy for businesses to find potential customers and for those customers to find what they’re looking for is an important part of that mission. Our tools help to connect business owners and customers, whether they’re around the corner or across the world from each other. Through our search and advertising programs, businesses find customers, publishers earn money from their online content and non-profits get donations and volunteers. These tools are how we make money, and they’re how millions of businesses do, too. This report details Google’s economic impact in the U.S., including state-by-state numbers of advertisers, publishers, and non-profits who use Google every day. It also includes stories of the real business owners behind those numbers. They are examples of businesses across the country that are using the web, and Google, to succeed online. Google was a small business when our mission was created. We are proud to share the tools that led to our success with other businesses that want to grow and thrive in this digital age. Sincerely, Jim Lecinski Vice President, Customer Solutions 2 Economic Impact | United States 2013 Nationwide Report Randy Gayner, Founder & Owner Glacier Guides West Glacier, Montana The web is working for American The Internet is where business is done businesses. -

Larry Page Developing the Largest Corporate Foundation in Every Successful Company Must Face: As Google Word.” the United States

LOWE —continued from front flap— Praise for $19.95 USA/$23.95 CAN In addition to examining Google’s breakthrough business strategies and new business models— In many ways, Google is the prototype of a which have transformed online advertising G and changed the way we look at corporate successful twenty-fi rst-century company. It uses responsibility and employee relations——Lowe Google technology in new ways to make information universally accessible; promotes a corporate explains why Google may be a harbinger of o 5]]UZS SPEAKS culture that encourages creativity among its where corporate America is headed. She also A>3/9A addresses controversies surrounding Google, such o employees; and takes its role as a corporate citizen as copyright infringement, antitrust concerns, and “It’s not hard to see that Google is a phenomenal company....At Secrets of the World’s Greatest Billionaire Entrepreneurs, very seriously, investing in green initiatives and personal privacy and poses the question almost Geico, we pay these guys a whole lot of money for this and that key g Sergey Brin and Larry Page developing the largest corporate foundation in every successful company must face: as Google word.” the United States. grows, can it hold on to its entrepreneurial spirit as —Warren Buffett l well as its informal motto, “Don’t do evil”? e Following in the footsteps of Warren Buffett “Google rocks. It raised my perceived IQ by about 20 points.” Speaks and Jack Welch Speaks——which contain a SPEAKS What started out as a university research project —Wes Boyd conversational style that successfully captures the conducted by Sergey Brin and Larry Page has President of Moveon.Org essence of these business leaders—Google Speaks ended up revolutionizing the world we live in. -

David Balto There Can Be Little Question That Internet Search Has

Internet Search Competition: Where is the Beef? David Balto1 There can be little question that Internet search has revolutionized how we live, communicate, learn and engage in commerce. Internet search gives hundreds of millions of people access to a wealth of information heretofore unattainable. Barriers to information and communication have fallen as the Internet has become the great marketplace of ideas and commerce. Internet search must be organized as any information system. Search providers all have developed sophisticated algorithms to try to determine relevancy and order information in a timely fashion. Some firms have suggested that search is being misused as a competitive weapon. The target du jour is Google. Google‘s critics have crystallized allegations of anticompetitive conduct under the banner of ―Search Neutrality.‖2 While the allegations take many forms, they boil down to three complaints. First, it is alleged that Google has penalized certain types of websites in its search results rather than basing its results on some objective, universal concept of relevance (if there is such a thing). Second, Google‘s critics allege that Google unfairly favors its own content in its search results as part of its Universal Search. Lastly, Google‘s critics challenge Google‘s transparency with respect to its algorithm and ranking standards. The European Commission decided to give the Search Neutrality arguments more legs, as it announced on November 30, 2010 that it has opened a formal investigation of Google‘s business practices pertaining -

Search the Full Text of Books and Discover New Ones

Search the full text of books and discover new ones With Google Book Search, you can quickly search the full text of books, from the first word on the first page to the last word in the final chapter. Find the perfect books for your purposes or discover ones you never even knew existed. Book Search works like web search Try a search on Google Book Search (http://books.google.com) or on Google.com. When we find a book whose content contains a match for your search terms, we’ll link to it in your search results. Browse books online Clicking on a book result, you’ll be able to see everything from a few short excerpts to the entire book, depending on a few different factors. • Full view: If we’ve determined that a book is out of copyright or the publisher or rightsholder has given us permission, you’ll be able to page through the entire book from start to finish. • Limited preview: If the publisher or author has provided the book through the Google Books Partner Program, you’ll be able to preview sample pages – typically about 20% of the book. • Snippet view: If a book is under copyright and the publisher or author is not part of the Partner Program, you’ll find bibliographic about the book and a few snippets of text from the book, showing your search term in context. • No preview available: For books where we’re unable to show snippets, you’ll see only bibliographic information. Search within the book Once you a find a title of interest, you can search within the book.