Utimmunohistochemical Detection of the Alternate Ink4a-Encoded

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Retinoblastoma Tumor-Suppressor Gene, the Exception That Proves the Rule

Oncogene (2006) 25, 5233–5243 & 2006 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9232/06 $30.00 www.nature.com/onc REVIEW The retinoblastoma tumor-suppressor gene, the exception that proves the rule DW Goodrich Department of Pharmacology & Therapeutics, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY, USA The retinoblastoma tumor-suppressor gene (Rb1)is transmission of one mutationally inactivated Rb1 allele centrally important in cancer research. Mutational and loss of the remaining wild-type allele in somatic inactivation of Rb1 causes the pediatric cancer retino- retinal cells. Hence hereditary retinoblastoma typically blastoma, while deregulation ofthe pathway in which it has an earlier onset and a greater number of tumor foci functions is common in most types of human cancer. The than sporadic retinoblastoma where both Rb1 alleles Rb1-encoded protein (pRb) is well known as a general cell must be inactivated in somatic retinal cells. To this day, cycle regulator, and this activity is critical for pRb- Rb1 remains an exception among cancer-associated mediated tumor suppression. The main focus of this genes in that its mutation is apparently both necessary review, however, is on more recent evidence demonstrating and sufficient, or at least rate limiting, for the genesis of the existence ofadditional, cell type-specific pRb func- a human cancer. The simple genetics of retinoblastoma tions in cellular differentiation and survival. These has spawned the hope that a complete molecular additional functions are relevant to carcinogenesis sug- understanding of the Rb1-encoded protein (pRb) would gesting that the net effect of Rb1 loss on the behavior of lead to deeper insight into the processes of neoplastic resulting tumors is highly dependent on biological context. -

DNA Microarrays (Gene Chips) and Cancer

DNA Microarrays (Gene Chips) and Cancer Cancer Education Project University of Rochester DNA Microarrays (Gene Chips) and Cancer http://www.biosci.utexas.edu/graduate/plantbio/images/spot/microarray.jpg http://www.affymetrix.com Part 1 Gene Expression and Cancer Nucleus Proteins DNA RNA Cell membrane All your cells have the same DNA Sperm Embryo Egg Fertilized Egg - Zygote How do cells that have the same DNA (genes) end up having different structures and functions? DNA in the nucleus Genes Different genes are turned on in different cells. DIFFERENTIAL GENE EXPRESSION GENE EXPRESSION (Genes are “on”) Transcription Translation DNA mRNA protein cell structure (Gene) and function Converts the DNA (gene) code into cell structure and function Differential Gene Expression Different genes Different genes are turned on in different cells make different mRNA’s Differential Gene Expression Different genes are turned Different genes Different mRNA’s on in different cells make different mRNA’s make different Proteins An example of differential gene expression White blood cell Stem Cell Platelet Red blood cell Bone marrow stem cells differentiate into specialized blood cells because different genes are expressed during development. Normal Differential Gene Expression Genes mRNA mRNA Expression of different genes results in the cell developing into a red blood cell or a white blood cell Cancer and Differential Gene Expression mRNA Genes But some times….. Mutations can lead to CANCER CELL some genes being Abnormal gene expression more or less may result -

Mitosis Vs. Meiosis

Mitosis vs. Meiosis In order for organisms to continue growing and/or replace cells that are dead or beyond repair, cells must replicate, or make identical copies of themselves. In order to do this and maintain the proper number of chromosomes, the cells of eukaryotes must undergo mitosis to divide up their DNA. The dividing of the DNA ensures that both the “old” cell (parent cell) and the “new” cells (daughter cells) have the same genetic makeup and both will be diploid, or containing the same number of chromosomes as the parent cell. For reproduction of an organism to occur, the original parent cell will undergo Meiosis to create 4 new daughter cells with a slightly different genetic makeup in order to ensure genetic diversity when fertilization occurs. The four daughter cells will be haploid, or containing half the number of chromosomes as the parent cell. The difference between the two processes is that mitosis occurs in non-reproductive cells, or somatic cells, and meiosis occurs in the cells that participate in sexual reproduction, or germ cells. The Somatic Cell Cycle (Mitosis) The somatic cell cycle consists of 3 phases: interphase, m phase, and cytokinesis. 1. Interphase: Interphase is considered the non-dividing phase of the cell cycle. It is not a part of the actual process of mitosis, but it readies the cell for mitosis. It is made up of 3 sub-phases: • G1 Phase: In G1, the cell is growing. In most organisms, the majority of the cell’s life span is spent in G1. • S Phase: In each human somatic cell, there are 23 pairs of chromosomes; one chromosome comes from the mother and one comes from the father. -

P14ARF Inhibits Human Glioblastoma–Induced Angiogenesis by Upregulating the Expression of TIMP3

P14ARF inhibits human glioblastoma–induced angiogenesis by upregulating the expression of TIMP3 Abdessamad Zerrouqi, … , Daniel J. Brat, Erwin G. Van Meir J Clin Invest. 2012;122(4):1283-1295. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI38596. Research Article Oncology Malignant gliomas are the most common and the most lethal primary brain tumors in adults. Among malignant gliomas, 60%–80% show loss of P14ARF tumor suppressor activity due to somatic alterations of the INK4A/ARF genetic locus. The tumor suppressor activity of P14ARF is in part a result of its ability to prevent the degradation of P53 by binding to and sequestering HDM2. However, the subsequent finding of P14ARF loss in conjunction with TP53 gene loss in some tumors suggests the protein may have other P53-independent tumor suppressor functions. Here, we report what we believe to be a novel tumor suppressor function for P14ARF as an inhibitor of tumor-induced angiogenesis. We found that P14ARF mediates antiangiogenic effects by upregulating expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase–3 (TIMP3) in a P53-independent fashion. Mechanistically, this regulation occurred at the gene transcription level and was controlled by HDM2-SP1 interplay, where P14ARF relieved a dominant negative interaction of HDM2 with SP1. P14ARF-induced expression of TIMP3 inhibited endothelial cell migration and vessel formation in response to angiogenic stimuli produced by cancer cells. The discovery of this angiogenesis regulatory pathway may provide new insights into P53-independent P14ARF tumor-suppressive mechanisms that have implications for the development of novel therapies directed at tumors and other diseases characterized by vascular pathology. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/38596/pdf Research article P14ARF inhibits human glioblastoma–induced angiogenesis by upregulating the expression of TIMP3 Abdessamad Zerrouqi,1 Beata Pyrzynska,1,2 Maria Febbraio,3 Daniel J. -

Review Article PTEN Gene: a Model for Genetic Diseases in Dermatology

The Scientific World Journal Volume 2012, Article ID 252457, 8 pages The cientificWorldJOURNAL doi:10.1100/2012/252457 Review Article PTEN Gene: A Model for Genetic Diseases in Dermatology Corrado Romano1 and Carmelo Schepis2 1 Unit of Pediatrics and Medical Genetics, I.R.C.C.S. Associazione Oasi Maria Santissima, 94018 Troina, Italy 2 Unit of Dermatology, I.R.C.C.S. Associazione Oasi Maria Santissima, 94018 Troina, Italy Correspondence should be addressed to Carmelo Schepis, [email protected] Received 19 October 2011; Accepted 4 January 2012 Academic Editors: G. Vecchio and H. Zitzelsberger Copyright © 2012 C. Romano and C. Schepis. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. PTEN gene is considered one of the most mutated tumor suppressor genes in human cancer, and it’s likely to become the first one in the near future. Since 1997, its involvement in tumor suppression has smoothly increased, up to the current importance. Germline mutations of PTEN cause the PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS), which include the past-called Cowden, Bannayan- Riley-Ruvalcaba, Proteus, Proteus-like, and Lhermitte-Duclos syndromes. Somatic mutations of PTEN have been observed in glioblastoma, prostate cancer, and brest cancer cell lines, quoting only the first tissues where the involvement has been proven. The negative regulation of cell interactions with the extracellular matrix could be the way PTEN phosphatase acts as a tumor suppressor. PTEN gene plays an essential role in human development. A recent model sees PTEN function as a stepwise gradation, which can be impaired not only by heterozygous mutations and homozygous losses, but also by other molecular mechanisms, such as transcriptional regression, epigenetic silencing, regulation by microRNAs, posttranslational modification, and aberrant localization. -

Wnt-Independent and Wnt-Dependent Effects of APC Loss on the Chemotherapeutic Response

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Wnt-Independent and Wnt-Dependent Effects of APC Loss on the Chemotherapeutic Response Casey D. Stefanski 1,2 and Jenifer R. Prosperi 1,2,3,* 1 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46617, USA; [email protected] 2 Mike and Josie Harper Cancer Research Institute, South Bend, IN 46617, USA 3 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Indiana University School of Medicine-South Bend, South Bend, IN 46617, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-574-631-4002 Received: 30 September 2020; Accepted: 20 October 2020; Published: 22 October 2020 Abstract: Resistance to chemotherapy occurs through mechanisms within the epithelial tumor cells or through interactions with components of the tumor microenvironment (TME). Chemoresistance and the development of recurrent tumors are two of the leading factors of cancer-related deaths. The Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC) tumor suppressor is lost in many different cancers, including colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer, and its loss correlates with a decreased overall survival in cancer patients. While APC is commonly known for its role as a negative regulator of the WNT pathway, APC has numerous binding partners and functional roles. Through APC’s interactions with DNA repair proteins, DNA replication proteins, tubulin, and other components, recent evidence has shown that APC regulates the chemotherapy response in cancer cells. In this review article, we provide an overview of some of the cellular processes in which APC participates and how they impact chemoresistance through both epithelial- and TME-derived mechanisms. Keywords: adenomatous polyposis coli; chemoresistance; WNT signaling 1. -

Teacher Background on P53 Tumor Suppressor Protein

Cancer Lab p53 – Teacher Background on p53 Tumor Suppressor Protein Note: The Teacher Background Section is meant to provide information for the teacher about the topic and is tied very closely to the PowerPoint slide show. For greater understanding, the teacher may want to play the slide show as he/she reads the background section. For the students, the slide show can be used in its entirety or can be edited as necessary for a given class. What Is p53 and Where Is the Gene Located? While commonly known as p53, the official name of this gene is Tumor Protein p53 and its official symbol is TP53. TheTP53 gene codes for the TP53 (p53) protein which acts as a tumor suppressor and works in response to DNA damage to orchestrate the repair of damaged DNA. If the DNA cannot be repaired, the p53 protein prevents the cell from dividing and signals it to undergo apoptosis (programmed cell death). The name p53 is due to protein’s 53 kilo-Dalton molecular mass. The gene which codes for this protein is located on the short (p) arm of chromosome 17 at position 13.1 (17p13.1). The gene begins at base pair 7,571,719 and ends at base pair 7, 590,862 making it 19,143 base pairs long. (1, 2) What Does the p53 Gene Look Like When Translated Into Protein? The TP53 gene has 11 exons and a very large 10 kb intron between exons 1 and 2. In humans, exon 1 is non-coding and it has been shown that this region could form a stable stem-loop structure which binds tightly to normal p53 but not to mutant p53 proteins. -

Interaction of Cdc2 and Rum1 Regulates Start and S-Phase in Fission Yeast

Journal of Cell Science 108, 3285-3294 (1995) 3285 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1995 JCS8905 Interaction of cdc2 and rum1 regulates Start and S-phase in fission yeast Karim Labib1,2,3, Sergio Moreno3 and Paul Nurse1,2,* 1ICRF Cell Cycle Laboratory, Department of Biochemistry, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX1 1QU, UK 2ICRF, PO Box 123, Lincolns Inn Fields, London WC2A 3PX, UK 3Instituto de Microbiologia-Bioquimica, CSIC/Universidad de Salamanca, Edificio Departamental, Campus Miguel de Unamuno, 37007 Salamanca, Spain *Author for correspondence SUMMARY The p34cdc2 kinase is essential for progression past Start in rum1, can disrupt the dependency of S-phase upon mitosis, the G1 phase of the fission yeast cell cycle, and also acts in resulting in an extra round of S-phase in the absence of G2 to promote mitotic entry. Whilst very little is known mitosis. We show that cdc2 and rum1 interact in this about the G1 function of cdc2, the rum1 gene has recently process, and describe dominant cdc2 mutants causing been shown to encode an important regulator of Start in multiple rounds of S-phase in the absence of mitosis. We fission yeast, and a model for rum1 function suggests that suggest that interaction of rum1 and cdc2 regulates Start, it inhibits p34cdc2 activity. Here we present genetic data and this interaction is important for the regulation of S- cdc2 suggesting that rum1 maintains p34 in a pre-Start G1 phase within the cell cycle. form, inhibiting its activity until the cell achieves the critical mass required for Start, and find that in the absence of rum1 p34cdc2 has increased Start activity in vivo. -

The Cell Cycle & Mitosis

The Cell Cycle & Mitosis Cell Growth The Cell Cycle is G1 phase ___________________________________ _______________________________ During the Cell Cycle, a cell ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Anaphase Cell Division ___________________________________ Mitosis M phase M ___________________________________ S phase replication DNA Interphase Interphase is ___________________________ ___________________________________ G2 phase Interphase is divided into three phases: ___, ___, & ___ G1 Phase S Phase G2 Phase The G1 phase is a period of The S phase replicates During the G2 phase, many of activity in which cells _______ ________________and the organelles and molecules ____________________ synthesizes _______ molecules. required for ____________ __________ Cells will When DNA replication is ___________________ _______________ and completed, _____________ When G2 is completed, the cell is synthesize new ___________ ____________________ ready to enter the ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Mitosis are divided into four phases: _____________, ______________, _____________, & _____________ Below are cells in two different phases of the cell cycle, fill in the blanks using the word bank: Chromatin Nuclear Envelope Chromosome Sister Chromatids Nucleolus Spinder Fiber Centrosome Centrioles 5.._________ 1.__________ v 6..__________ 2.__________ 7.__________ 3.__________ 8..__________ 4.__________ v The Cell Cycle & Mitosis Microscope Lab: -

Label the Parts of the Cell Cycle Diagram and Briefly Describe What Is Happening: a B C D E F G H I J 1) Chromosomes Move To

Label the parts of the cell cycle diagram and briefly describe what is happening: A Interphase - cell is growing and preparing for division. B G1 - growth and normal cell function C S - DNA replication D G2 - growth, preparation for division, duplicate organelles E Prophase - nuclear envelope dissolves, mitotic apparatus set up, DNA condenses. F Metaphase - chromosome line up in center G Anaphase - sister chromatids separate and are pulled to poles of cell. H Telophase - nuclei reform, DNA relaxes into chromatin, cleaveage furrow or cell plate forms I Mitosis - nuclear division J Cytokinesis - the rest of the cell divides 1) Chromosomes move to the middle of the cell during what phase? 2) What are sister chromatids? 3) What holds the chromatids together? 4) When do the sister chromatids separate? 5) During which phase do chromosomes first become visible? 6) During which phase does the cleavage furrow start forming? 7) What is another name for mitosis? 8) What is the structure that breaks the spindle fiber into 2? 9) What makes up the mitotic apparatus? 10) Complete the table by checking the correct column for each statement. Statement Interphase Mitosis Cell growth occurs Nuclear division occurs Chromosomes are finishing moving into separate daughter cells. Normal functions occur Chromosomes are duplicated DNA synthesis occurs Cytoplasm divides immediately after this period Mitochondria and other organelles are made. The Animal Cell Cycle – Phases are out of order 11) Which cell is in metaphase? 12) Cells A and F show an early and late stage of the same phase of mitosis. What phase is it? 13) In cell A, what is the structure labeled X? 14) In cell F, what is the structure labeled Y? 15) Which cell is not in a phase of mitosis? 16) A new membrane is forming in B. -

List, Describe, Diagram, and Identify the Stages of Meiosis

Meiosis and Sexual Life Cycles Objective # 1 In this topic we will examine a second type of cell division used by eukaryotic List, describe, diagram, and cells: meiosis. identify the stages of meiosis. In addition, we will see how the 2 types of eukaryotic cell division, mitosis and meiosis, are involved in transmitting genetic information from one generation to the next during eukaryotic life cycles. 1 2 Objective 1 Objective 1 Overview of meiosis in a cell where 2N = 6 Only diploid cells can divide by meiosis. We will examine the stages of meiosis in DNA duplication a diploid cell where 2N = 6 during interphase Meiosis involves 2 consecutive cell divisions. Since the DNA is duplicated Meiosis II only prior to the first division, the final result is 4 haploid cells: Meiosis I 3 After meiosis I the cells are haploid. 4 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Prophase I: ¾ Chromosomes condense. Because of replication during interphase, each chromosome consists of 2 sister chromatids joined by a centromere. ¾ Synapsis – the 2 members of each homologous pair of chromosomes line up side-by-side to form a tetrad consisting of 4 chromatids: 5 6 1 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Prophase I: ¾ During synapsis, sometimes there is an exchange of homologous parts between non-sister chromatids. This exchange is called crossing over. 7 8 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis (2N=6) Prophase I: ¾ the spindle apparatus begins to form. ¾ the nuclear membrane breaks down: Prophase I 9 10 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, 4 Possible Metaphase I Arrangements: Metaphase I: ¾ chromosomes line up along the equatorial plate in pairs, i.e. -

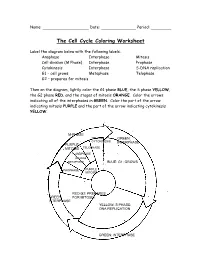

The Cell Cycle Coloring Worksheet

Name: Date: Period: The Cell Cycle Coloring Worksheet Label the diagram below with the following labels: Anaphase Interphase Mitosis Cell division (M Phase) Interphase Prophase Cytokinesis Interphase S-DNA replication G1 – cell grows Metaphase Telophase G2 – prepares for mitosis Then on the diagram, lightly color the G1 phase BLUE, the S phase YELLOW, the G2 phase RED, and the stages of mitosis ORANGE. Color the arrows indicating all of the interphases in GREEN. Color the part of the arrow indicating mitosis PURPLE and the part of the arrow indicating cytokinesis YELLOW. M-PHASE YELLOW: GREEN: CYTOKINESIS INTERPHASE PURPLE: TELOPHASE MITOSIS ANAPHASE ORANGE METAPHASE BLUE: G1: GROWS PROPHASE PURPLE MITOSIS RED:G2: PREPARES GREEN: FOR MITOSIS INTERPHASE YELLOW: S PHASE: DNA REPLICATION GREEN: INTERPHASE Use the diagram and your notes to answer the following questions. 1. What is a series of events that cells go through as they grow and divide? CELL CYCLE 2. What is the longest stage of the cell cycle called? INTERPHASE 3. During what stage does the G1, S, and G2 phases happen? INTERPHASE 4. During what phase of the cell cycle does mitosis and cytokinesis occur? M-PHASE 5. During what phase of the cell cycle does cell division occur? MITOSIS 6. During what phase of the cell cycle is DNA replicated? S-PHASE 7. During what phase of the cell cycle does the cell grow? G1,G2 8. During what phase of the cell cycle does the cell prepare for mitosis? G2 9. How many stages are there in mitosis? 4 10. Put the following stages of mitosis in order: anaphase, prophase, metaphase, and telophase.