Cliffhangers and Sequels: Stories, Serials, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Summer 2019 Vol.21, No.3 Screenwriter Film | Television | Radio | Digital Media

CANADIAN CANADA $7 SUMMER 2019 VOL.21, NO.3 SCREENWRITER FILM | TELEVISION | RADIO | DIGITAL MEDIA A Rock Star in the Writers’ Room: Bringing Jann Arden to the small screen Crafting Canadian Horror Stories — and why we’re so good at it Celebrating the 23rd annual WGC Screenwriting Awards Emily Andras How she turned PM40011669 Wynonna Earp into a fan phenomenon Congratulations to Emily Andras of SPACE’s Wynonna Earp, Sarah Dodd of CTV’s Cardinal, and all of the other 2019 WGC Screenwriting Award winners. Proud to support Canada’s creative community. CANADIAN SCREENWRITER The journal of the Writers Guild of Canada Vol. 21 No. 3 Summer 2019 ISSN 1481-6253 Publication Mail Agreement Number 400-11669 Publisher Maureen Parker Editor Tom Villemaire [email protected] Contents Director of Communications Lana Castleman Cover Editorial Advisory Board There’s #NoChill When it Comes Michael Amo to Emily Andras’s Wynonna Earp 6 Michael MacLennan How 2019’s WGC Showrunner Award winner Emily Susin Nielsen Andras and her room built a fan and social media Simon Racioppa phenomenon — and why they’re itching to get back in Rachel Langer the saddle for Wynonna’s fourth season. President Dennis Heaton (Pacific) By Li Robbins Councillors Michael Amo (Atlantic) Features Mark Ellis (Central) What Would Jann Do? 12 Marsha Greene (Central) That’s exactly the question co-creators Leah Gauthier Alex Levine (Central) and Jennica Harper asked when it came time to craft a Anne-Marie Perrotta (Quebec) heightened (and hilarious) fictional version of Canadian Andrew Wreggitt (Western) icon Jann Arden’s life for the small screen. -

Foregrounding Narrative Production in Serial Fiction Publishing

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2017 To Start, Continue, and Conclude: Foregrounding Narrative Production in Serial Fiction Publishing Gabriel E. Romaguera University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Romaguera, Gabriel E., "To Start, Continue, and Conclude: Foregrounding Narrative Production in Serial Fiction Publishing" (2017). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 619. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/619 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TO START, CONTINUE, AND CONCLUDE: FOREGROUNDING NARRATIVE PRODUCTION IN SERIAL FICTION PUBLISHING BY GABRIEL E. ROMAGUERA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2017 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF Gabriel E. Romaguera APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Valerie Karno Carolyn Betensky Ian Reyes Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2017 Abstract This dissertation explores the author-text-reader relationship throughout the publication of works of serial fiction in different media. Following Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of authorial autonomy within the fields of cultural production, I trace the outside influence that nonauthorial agents infuse into the narrative production of the serialized. To further delve into the economic factors and media standards that encompass serial publishing, I incorporate David Hesmondhalgh’s study of market forces, originally used to supplement Bourdieu’s analysis of fields. -

Orange County Board of Commissioners Agenda Business

Orange County Board of Commissioners Agenda Business Meeting Note: Background Material December 10, 2019 on all abstracts 7:00 p.m. available in the Southern Human Services Center Clerk’s Office 2501 Homestead Road Chapel Hill, NC 27514 Compliance with the “Americans with Disabilities Act” - Interpreter services and/or special sound equipment are available on request. Call the County Clerk’s Office at (919) 245-2130. If you are disabled and need assistance with reasonable accommodations, contact the ADA Coordinator in the County Manager’s Office at (919) 245-2300 or TDD# 919-644-3045. 1. Additions or Changes to the Agenda PUBLIC CHARGE The Board of Commissioners pledges its respect to all present. The Board asks those attending this meeting to conduct themselves in a respectful, courteous manner toward each other, county staff and the commissioners. At any time should a member of the Board or the public fail to observe this charge, the Chair will take steps to restore order and decorum. Should it become impossible to restore order and continue the meeting, the Chair will recess the meeting until such time that a genuine commitment to this public charge is observed. The BOCC asks that all electronic devices such as cell phones, pagers, and computers should please be turned off or set to silent/vibrate. Please be kind to everyone. Arts Moment – Andrea Selch joined the board of Carolina Wren Press 2001, after the publication of her poetry chapbook, Succory, which was #2 in the Carolina Wren Press poetry chapbook series. She has an MFA from UNC-Greensboro, and a PhD from Duke University, where she taught creative writing from 1999 until 2003. -

Fandom, Fan Fiction and the Creative Mind ~Masterthesis Human Aspects of Information Technology~ Tilburg University

Fandom, fan fiction and the creative mind ~Masterthesis Human Aspects of Information Technology~ Tilburg University Peter Güldenpfennig ANR: 438352 Supervisors: dr. A.M. Backus Prof. dr. O.M. Heynders Fandom, fan fiction and the creative mind Peter Güldenpfennig ANR: 438352 HAIT Master Thesis series nr. 11-010 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION SCIENCES, MASTER TRACK HUMAN ASPECTS OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY, AT THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES OF TILBURG UNIVERSITY Thesis committee: [Dr. A.M. Backus] [Prof. dr. O.M. Heynders] Tilburg University Faculty of Humanities Department of Communication and Information Sciences Tilburg center for Cognition and Communication (TiCC) Tilburg, The Netherlands September 2011 Table of contents Introduction..........................................................................................................................................2 1. From fanzine to online-fiction, a short history of modern fandom..................................................5 1.1 Early fandom, the 1930's...........................................................................................................5 1.2 The start of media fandom, the 1960's and 1970's.....................................................................6 1.3 Spreading of media fandom and crossover, the 1980's..............................................................7 1.4 Fandom and the rise of the internet, online in the 1990's towards the new millennium............9 -

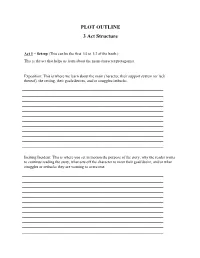

YES Plot Outline (Pdf)

PLOT OUTLINE 3 Act Structure Act 1 – Set-up (This can be the first 1/4 to 1/3 of the book.) This is the act that helps us learn about the main character/protagonist. Exposition: This is where we learn about the main character, their support system (or lack thereof), the setting, their goals/desires, and/or struggles/setbacks. Inciting Incident: This is where you set in motion the purpose of the story, why the reader wants to continue reading the story, what sets off the character to meet their goal/desire, and/or what struggles or setbacks they are wanting to overcome. Plot Point One: Setting the plot in a new direction. Meeting a bump in the road. FIRST PLOT TWIST! Act 2 – Confrontation (This can be the middle 1/3 to 1/2 of the book.) This act is meant to show us how the protagonist is able/unable to deal with the setbacks and complications that surface. This is an emotional journey for the protagonist. Rising Action(s): The small obstacles (and hopefully their resolutions) and a complication (or two) that could be serious/dangerous is introduced. Midpoint: This is where the protagonist’s world crashes down and makes them feel as if they have hit rock bottom (emotionally, physically, financially, morally, etc.). The DARK MOMENT! Plot Point Two: Another new direction. Another bump in the road. SECOND PLOT TWIST! Act 3 – Resolution (This can be the last 1/4 to 1/3 of the book.) This act is meant to show the resolution between the protagonist and the antagonist. -

More on Narrative Closure

Journal of Literary Semantics 2016; 45(1): 21–48 Tobias Klauk, Tilmann Köppe* and Edgar Onea More on narrative closure DOI 10.1515/jls-2016-0003 Abstract: In this article, we shall contribute to the theory of narrative closure. In pre-theoretical terms, a narrative features closure if it has an ending. We start by giving a general introduction into the closure phenomenon. Next, we offer a reconstruction of Noël Carroll’s (2007. Narrative closure. Philosophical Studies 135.1–15) erotetic account of narrative closure, according to which a narrative exhibits closure (roughly) if readers have a “feeling of finality” which in turn is based on the judgment that the presiding macro questions posed by the plot of the narrative get answered. We then discuss a number of questions raised by Carroll’s account, namely whether a definition of “narrative closure” based on his account is either too inclusive or too exclusive; whether narrative closure is a property of narratives or of plots; whether narrative closure comes in grades; whether “narrative closure” is a restrictive notion; and whether “narrative closure” should be ascribed online (incrementally) or on the basis of all- things-considered ex post interpretations. Our answers to these questions are couched in terms of refined definitions, for this allows us to keep track of the progress and facilitates comparisons between the different proposals developed. Finally, we offer a definition of “narrative closure” that summarizes our amend- ments to Carroll’s theory. Keywords: narrative closure, plot, Carroll, erotetic, finality 1 Introduction Some narratives have an ending, others don’t. -

TNHA Curriculum Planning Document Subject: English Year: 10

TNHA Curriculum Planning Document Subject: English Year: 10 Autumn 1 Autumn 2 Spring 1 Spring 2 Summer 1 Summer 2 Subject Literature Paper 2 – Literature Paper 2 – A Literature Paper 1 – Literature Paper 1 - Literature Paper 1 – Literature Paper 1 – Content A Christmas Carol Christmas Carol An Inspector Calls An Inspector Calls Power & Conflict Poetry Power & Conflict Poetry by Charles Dickens by Charles Dickens by J.B. Priestley by J.B. Priestley Anthology by various Anthology by various Exam Poets Poets Board: AQA Language Paper 1 - Language Paper 1 – Language Paper 2 - Language Paper 2 - Language Paper 1 - Language Paper 1 – Section A Section B Section A Section B Section A Section B MOCKS - Language Literary Authorial Intention Authorial Intention Authorial Intention Authorial Intention Authorial Intention Authorial Intention Concepts Character Character Character Character Poem Poem Form – Novel Form – Novel Form – Play Form – Play Form Form Narrative Structure Narrative Structure Narrative Structure Narrative Structure Structure Structure Reader Theory – Reader Theory – Refer Reader Theory – Refer to Reader Theory – Reader Theory Reader Theory Refer to Literary to Literary Concept Literary Concept Booklet Refer to Literary Romanticism – Refer to Romanticism – Refer to Concept Booklet Booklet Concept Booklet Literary Concept Booklet Literary Concept Booklet Ideas in 4. Politics Ideas & 4. Politics Ideas & 4. Politics Ideas & 4. Politics Ideas & 1. Culture & Identity 1. Culture & Identity Context / Economic Systems Economic Systems Economic Systems Economic Systems 2. Empire & Colonialism 2. Empire & Colonialism 5. Prejudice & 5. Prejudice & 5. Prejudice & 5. Prejudice & 3. Personal Identity 3. Personal Identity Cultural Discrimination Discrimination Discrimination Discrimination Capital 7. Social Class 7. Social Class 7. -

Cinema with Lots of Screens? 3

Match the types of films with the phrases that are most likely to describe them. a thriller a romantic comedy an animated film a sci-fi film a horror film a costume drama 1. An all-action movie with great stunts and a real cliffhanger of an ending that will have you on the edge of your seat. 2. Set on a star cruiser in the distant future, this film has great special effects. 3. A hilarious new film, about two unlikely lovers, which will have you laughing out loud. 4. Based on a novel by Jane Austen, this new adaptation by William Jones has been filmed on location at Harewood House in Hampshire. 5. A fantastic new computer-generated cartoon, featuring the voice of Eddie Murphy as the donkey. 6. This new film will scare you to death. Now match the words in italics in the descriptions to the definitions below. 1. exciting 2. not filmed in a studio 3. the story comes from (a novel) 4. dangerous action sequences like car chases or people falling from skyscrapers 5. amazing, impossible visual sequences, often created by computers 6. changing a novel to a film screenplay 7. where the story takes place 8. exciting end – you want to know what happens © Macmillan Publishers Ltd 2005 Downloaded from the vocabulary section in www.onestopenglish.com Use the words below to answer the questions. the latest release the soundtrack a trailer the credits a multiplex the rushes the titles a screen test 1. What do you call the songs and background music to a film? 2. -

The Social and Literary Relevance of Comic Books

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Filip Hatala We Live in a Society: The Social and Literary Relevance of Comic Books Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Christopher Adam Rance, M.A. 2020 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. Filip Hatala I would hereby like to thank my supervisor Christopher Adam Rance, M.A. for his patience, time and helpful input. I would also like to thank my family and friends who have supported me all throughout these 5 years of my bachelor’s studies. Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 6 1 History of Superhero Comics: The Golden Age and Superman ........................................... 8 1.1 The Caped Crusader in the Night .................................................................................... 9 1.2 World War II and the Super Soldier .............................................................................. 11 1.3 Social Norms Change and a Wonder Arrives ................................................................ 13 1.4 World War II and the Great Depression Come to an End, but the Golden Age Continues. ..................................................................................................................... 15 2 The Cold War Picks up Steam, as Gold Turns to Silver .................................................... -

Writing Creative Nonfiction Course Guidebook

Topic Literature Subtopic & Language Writing Writing Creative Nonfiction Course Guidebook Professor Tilar J. Mazzeo Colby College PUBLISHED BY: THE GREAT COURSES Corporate Headquarters 4840 Westfi elds Boulevard, Suite 500 Chantilly, Virginia 20151-2299 Phone: 1-800-832-2412 Fax: 703-378-3819 www.thegreatcourses.com Copyright © The Teaching Company, 2012 Printed in the United States of America This book is in copyright. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of The Teaching Company. Tilar J. Mazzeo, Ph.D. Clara C. Piper Professor of English Colby College rofessor Tilar J. Mazzeo is the New York Times best-selling author of The Widow PClicquot: The Story of a Champagne Empire and the Woman Who Ruled It,the story of the rst international businesswoman in history, and The Secret of Chanel No. 5: The Intimate History of the World’s Most Famous Perfume. The Widow Clicquot won the 2008 Gourmand Award for the best book of wine literature published in the United States. Professor Mazzeo holds a Ph.D. in English and teaches British and European literature at Colby College, where she is the Clara C. Piper Professor of English. She has been the Jenny McKean Moore Writer-in-Residence at The George Washington University, and her writing on creative non ction techniques has appeared in recent collections such as Now Write! Nonfi ction: Memoir, Journalism, and Creative Nonfi ction Exercises from Today’s Best Writers. -

The Crossover Phenomenon in Young Adult Literature

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors College 2012 The Crossover Phenomenon in Young Adult Literature Keri Jo Carroll Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/honors_theses Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons THE CROSSOVER PHENOMENON IN YOUNG ADULT LITERATURE (TITLE) BY KERI JO CARROLL UNDERGRADUATE THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF UNDERGRADUATE DEPARTMENTAL HONORS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH, ALONG WITH THE HONORS COLLEGE, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 2012 YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS UNDERGRADUATE THESIS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THE THESIS REQUIREMENT FOR UNDERGRADUATE DEPARTMENTAL HONORS ;).1 a,pri I lc!J 12- DATE THESIS ADVISOR G � I 2_ ;z -7 G'-' DATE Carroll 1 Introduction Growing up as a child of the nineties, I was smack dab in the middle of one of the biggest movements in literature in recent years, and I had no idea it was going on. When I was nine, a humble book titled Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone (which I will refer to hereafter as simply Harry Potter) was released and I, being the fickle pre-adolescent that I was, did not immediately like it. A few months later, whether it was because I decided to give it another chance or the media frenzysurrounding the book forced me to reconsider my initial judgment, I pick up Harry Potter again and the rest is, as they say, history. I was about to go on one of the most exciting and ground-breaking rides in not just children's literature but all literature, without even knowing it.