Different Characterization of M. Butterfly in Play and the Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index of Authors

Index of Authors Abel, Richard 19, 20, 134, 135, 136, Alexander, David 441 Andre, Marle 92 Aros (= Alfred Rosenthal) 196, 225, 173 Alexander, lohn 274 Andres, Eduard P. 81 244, 249, 250 Abel, Viktor 400 Alexander, Scott 242, 325 Andrew, Geoff 4, 12, 176, 261,292 Aros, Andrew A. 9 Abercrombie, Nicholas 446 Alexander, William 73 Andrew, 1. Dudley 136, 246, 280, Aroseff, A. 155 Aberdeen, l.A. 183 Alexowitz, Myriam 292 330, 337, 367, 368 Arpe, Verner 4 Aberly, Rache! 233 Alfonsi, Laurence 315 Andrew, Paul 280 Arrabal, Fernando 202 About, Claude 318 Alkin, Glyn 393 Andrews, Bart 438 Arriens, Klaus 76 Abramson, Albert 436 Allan, Angela 6 Andrews, Nigel 306 Arrowsmith, William 201 Abusch, Alexander 121 Allan, Elkan 6 Andreychuk, Ed 38 Arroyo, lose 55 Achard, Maurice 245 Allan, Robin 227 Andriopoulos, Stefan 18 Arvidson, Linda 14 Achenbach, Michael 131 Allan, Sean 122 Andritzky, Christoph 429 Arzooni, Ora G. 165 Achternbusch, Herbert 195 Allardt-Nostitz, Felicitas 311 Anfang, Günther 414 Ascher, Steven 375 Ackbar, Abbas 325 Allen, Don 314 Ang, Ien 441, 446 Ash, Rene 1. 387 Acker, Ally 340 Allen, Jeanne Thomas 291 Angelopoulos, Theodoros 200 Ashbrook, lohn 220 Ackerknecht, Erwin 10, 415, 420 Allen, lerry C. 316 Angelucci, Gianfranco 238 Ashbury, Roy 193 Ackerman, Forrest }. 40, 42 Allen, Michael 249 Anger, Cedric 137 Ashby, lustine 144 Acre, Hector 279 Allen, Miriam Marx 277 Anger, Kenneth 169 Ashley, Leonard R.N. 46 Adair, Gilbert 5, 50, 328 Allen, Richard 254, 348, 370, 372 Angst-Nowik, Doris ll8 Asmus, Hans-Werner 7 Adam, Gerhard 58, 352 Allen, Robert C. -

M. Butterfly As Total Theatre

M. Butterfly as Total Theatre Mª Isabel Seguro Gómez Universitat de Barcelona [email protected] Abstract The aim of this article is to analyse David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly from the perspective of a semiotics on theatre, following the work of Elaine Aston and George Savona (1991). The reason for such an approach is that Hwang’s play has mostly been analysed as a critique of the interconnections between imperialism and sexism, neglecting its theatricality. My argument is that the theatrical techniques used by the playwright are also a fundamental aspect to be considered in the deconstruction of the Orient and the Other. In a 1988 interview, David Henry Hwang expressed what could be considered as his manifest on theatre whilst M. Butterfly was still being performed with great commercial success on Broadway:1 I am generally interested in ways to create total theatre, theatre which utilizes whatever the medium has to offer to create an effect—just to keep an audience interested—whether there’s dance or music or opera or comedy. All these things are very theatrical, even makeup changes and costumes—possibly because I grew up in a generation which isn’t that acquainted with theatre. For theatre to hold my interest, it needs to pull out all its stops and take advantage of everything it has— what it can do better than film and television. So it’s very important for me to exploit those elements.… (1989a: 152-53) From this perspective, I would like to analyse the theatricality of M. Butterfly as an aspect of the play to which, traditionally, not much attention has been paid to as to its content and plot. -

The Miss Saigon Controversy

The Miss Saigon Controversy In 1990, theatre producer Cameron Mackintosh brought the musical Miss Saigon to Broadway following a highly successful run in London. Based on the opera Madame Butterfly, Miss Saigon takes place during the Vietnam War and focuses on a romance between an American soldier and a Vietnamese orphan named Kim. In the musical, Kim is forced to work at ‘Dreamland,’ a seedy bar owned by the half-French, half-Vietnamese character ‘the Engineer.’ The production was highly anticipated, generating millions of dollars in ticket sales before it had even opened. Controversy erupted, however, when producers revealed that Jonathan Pryce, a white British actor, would reprise his role as the Eurasian ‘Engineer.’ Asian American actor B.D. Wong argued that by casting a white actor in a role written for an Asian actor, the production supported the practice of “yellow-face.” Similar to “blackface” minstrel shows of the 19th and 20th centuries, “yellow-face” productions cast non-Asians in roles written for Asians, often relying on physical and cultural stereotypes to make broad comments about identity. Wong asked his union, Actors’ Equity Association, to “force Cameron Mackintosh and future producers to cast their productions with racial authenticity.” Actors’ Equity Association initially agreed and refused to let Pryce perform: “Equity believes the casting of Mr. Pryce as a Eurasian to be especially insensitive and an affront to the Asian community.” Moreover, many argued that the casting of Pryce further limited already scarce professional opportunities for Asian American actors. Frank Rich of The New York Times disagreed, sharply criticizing the union for prioritizing politics over talent: “A producer's job is to present the best show he can, and Mr. -

Fantasy, Narcissism and David Henry Hwang's M. Butterfly

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 554 Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research (ICHSSR 2021) Fantasy, Narcissism and David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly Shu-Yuan Chang1 1School of Foreign Languages, Zhaoqing University, Zhaoqing 526061, China *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly deconstructs Giacomo Puccini’s Madame Butterfly by entwining a fact happened in 1986 — a French diplomat Bernard Bouriscot who has a multi-year affair with a Chinese man disguised as a woman. Hwang displays how cultural imperialism and the stereotype of the Asian persona through the protagonist Gallimard who unconsciously perceives superiority of Western power over Eastern weakness, and the Western colonial male over the Asian female. Gallimard falls in love with the Chinese actress Song Liling to whom he projects his fantasy of a “perfect woman” without noticing the fact Song Liling is a man and a spy. His relationship with Song can be interpreted by concept of the Other in Western concept. This study discusses how Gallimard in M. Butterfly reflects the “Narcissus myth”, how “Othered self” and “selfed Other” work upon him as well as how Song, as a man, satisfies his Western superiority to the power of control and fantasy to an Oriental woman. Keywords: Cultural imperialism, Stereotype of the Asian persona, Superiority, Fantasy, Narcissus myth, The Other concluded that the diplomat [Bouriscot] must have fallen 1. INTRODUCTION in love not with a person but with a fantasy stereotype” When it comes to the issue of the East and the West, [1]. -

From M. Butterfly to Madame Butterfly 從《蝴蝶君》到《蝴蝶夫人》: 逆寫帝國後殖民理論

Writing Back to the Empire: From M. Butterfly to Madame Butterfly 從《蝴蝶君》到《蝴蝶夫人》: 逆寫帝國後殖民理論 Presented in FILLM International Congress Re-imagining Language and Literature for the 21st Century at Assumption University, Bangkok, Thailand. August 18-23, 2002 Cecilia Hsueh Chen Liu 劉雪珍 English Department 英文系 Fu Jen University, Taiwan 輔仁大學 Abstract Keywords: parody 諧擬,travestism 性別反串、扮/變裝, hegemony 霸權, Dialogism 對話論,Bakhtinian concept 巴赫汀理論,Eurocentric ideology 歐洲中心論,colonial mimicry 殖民模仿,simulacrum 擬像, post-colonial theory 後殖民理論 Most critical concerns of David Henry Hwang's M. Butterfly center around the issues of gender, identity, ethnicity, theatricality, and subversions of the binary oppositions such as West vs. East, Male vs. Female, Master vs. Slave, Victor vs. Victim, Colonizer vs. Colonized, Reality vs. Fantasy, Mind vs. Body and so on. It is agreed that Hwang successfully parodies Madame Butterfly by means of transvestism and transformation of western male into the critical butterfly. The transformation of the characters, either Gallimard or Song, demonstrates the dynamics or ambivalence or destabilization of gender, identity and culture politics. Bakhtinian concept of dialogism is used to expound the textuality and meaning of the play, while Gransci’s hegemony is cited to describe the western cultural leadership. Edward Said’s Orientalism is applied to explain the Eurocentric ideology as well as misconception. Kathryn Remen makes good use of Michel Foucault’s concepts of discipline and punishment and presents a convincing case of reading M. Butterfly as “the theatre of punishment” in which we, Gallimard’s ideal audience, align ourselves with the punishing power and witness our prisoner Gallimard’s death penalty for his over-indulgence in the fantasy of the perfect woman. -

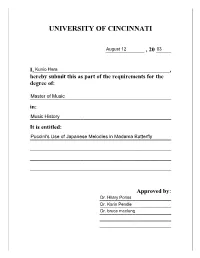

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ PUCCINI’S USE OF JAPANESE MELODIES IN MADAMA BUTTERFLY A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Kunio Hara B.M., University of Cincinnati, 2000 Committee Chair: Dr. Hilary Poriss ABSTRACT One of the more striking aspects of exoticism in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly is the extent to which the composer incorporated Japanese musical material in his score. From the earliest discussion of the work, musicologists have identified many Japanese melodies and musical characteristics that Puccini used in this work. Some have argued that this approach indicates Puccini’s preoccupation with creating an authentic Japanese setting within his opera; others have maintained that Puccini wanted to produce an exotic atmosphere -

Madame Butterfly Source Material

MADAMA BUTTERFLY SOURCE MATERIAL THE EVOLUTION OF MADAME BUTTERFLY The story of Madama Butterfly, Pucciniʼs beloved opera of the young Japanese geisha doomed to an unhappy end, still fascinates the public today. However, much like the life cycle of the butterfly, the story of Madama Butterfly underwent considerable transformation over time before the opera emerging in its present form. The beginnings of the opera can be traced back to a tabloid-like story of a young woman with a broken heart in Japan. At the turn of the 19th century, with the opening of Japan in 1894 by Commodore Matthew Perry, the publicʼs fascination with all things Japanese – japonisme - was evident in popular culture. American writer John Luther Longʼs short story, Madame Butterfly, was first published in the January 1898 issue of Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine. The author was purported inspired by a true story relayed to him by his sister, the wife of a missionary living in Nagasaki. However, French author Pierre Loti's popular semi- autobiographical novel, Madame Chrysanthème, first published in1887, also has a very similar storyline of a Japanese geisha who marries a naval officer named Pierre. Lotiʼs novel even inspired an 1893 opera version by Charles Messager. Longʼs later version of the story has the notable addition of the suicide attempt by Cho- Cho-San after her abandonment by the selfish Lieutenant Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton. At the climax of Longʼs 18-page version, Suzuki thwarts the heroineʼs suicide attempt. At the key moment, Suzuki makes Trouble, the child of Butterfly and Pinkerton cry, and Cho-Cho-San realizes that she must care for her child. -

Not So Silent: Women in Cinema Before Sound Stockholm Studies in Film History 1

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Not so Silent: Women in Cinema before Sound Stockholm Studies in Film History 1 Not so Silent Women in Cinema before Sound Edited by Sofia Bull and Astrid Söderbergh Widding ©Sofia Bull, Astrid Söderbergh Widding and Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis, Stockholm 2010 Cover page design by Bart van der Gaag. Original photograph of Alice Terry. ISBN 978-91-86071-40-0 Printed in Sweden by US-AB, Stockholm 2010. Distributor eddy.se ab, Visby, Sweden. Acknowledgements Producing a proceedings volume is always a collective enterprise. First and foremost, we wish to thank all the contributors to the fifth Women and the Silent Screen conference in Stockholm 2008, who have taken the trouble to turn their papers into articles and submitted them to review for this proceed- ings volume. Margareta Fathli, secretary of the Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis, de- serves a particular mention for her engagement in establishing the new series Stockholm Studies in Film History; an ideal framework for this publication. A particular thanks goes to Lawrence Webb, who has copy–edited the book with a seemingly never–ending patience. We also owe many thanks to Bart van der Gaag for making the cover as well as for invaluable assistance in the production process. Finally, we are most grateful to the Holger and Thyra Lauritzen Foundation for a generous grant, as well as to the Department of Cinema Studies which has also contributed generously to funding this volume. Stockholm 30 April 2010 Sofia Bull & Astrid Söderbergh Widding 5 Contributors Marcela de Souza Amaral is Professor at UFF (Universidade Federal Fluminense––UFF) in Brazil since 2006. -

Madama Butterfly

Madama Butterfly PRODUCTION INFORMATION Music: Giacomo Puccini Text (Italian): Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica World Premiere: Milan, La Scala February 17, 1904 Final Dress Rehearsal Date: Monday, January 13, 2014 Note: the following times are approximate Act I: 10:30am – 11:30am Intermission (Lunch): 11:30am – 12:00pm Act II, Part 1: 12:00pm – 1:00pm Intermission: 1:00pm – 1:25pm Act II, Part 2: 1:25pm – 2:00pm Cast: Cio-Cio-San Amanda Echalaz Suzuki Elizabeth DeShong Pinkerton Bryan Hymel Sharpless Scott Hendricks Production Team: Conductor Philippe Auguin Production Anthony Minghella Director and Choreographer Carolyn Choa Set Designer Michael Levine Costume Designer Han Feng Lighting Designer Peter Mumford Puppetry Blind Summit Theatre 2 Table of Contents Production Information 2 An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials 4 Meet the Characters 5 The Story of Madama Butterfly Synopsis 6 Guiding Questions 8 The History of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly 9 Guided Listening Dovunque al mondo lo Yankee… 13 Cio-Cio-San 15 Vogliatemi bene 17 Un bel dì 19 Yamadori, ancor le pene 20 Addio, fiorito asil 22 Con onor muore 24 Madama Butterfly Resources About the Composer 26 Exoticism and Opera 29 Online Resources 32 Additional Resources The Emergence of Opera 34 Metropolitan Opera House Facts 38 Reflections after the Opera 40 A Guide to Voice Parts and Families of the Orchestra 41 Glossary 42 References Works Consulted 46 3 An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials The goal of Pathways for Understanding materials is to provide multiple “pathways” for learning about a specific opera as well as the operatic art form, and to allow teachers to create lessons that work best for their particular teaching style, subject area, and class of students. -

Madama Butterfly Composed By: Giacomo Puccini

Presents Madama Butterfly Composed by: Giacomo Puccini A Japanese Tragedy in Two Acts Study Guide 2018-2019 Season Please join us in thanking the generous sponsors of the Education and Outreach Activities of Virginia Opera: Alexandria Commission for the Arts ARTSFAIRFAX Chesapeake Fine Arts Commission Chesterfield County City of Norfolk CultureWorks Dominion Energy Franklin-Southampton Charities Fredericksburg Festival for the Performing Arts Herndon Foundation Henrico Education Fund National Endowment for the Arts Newport News Arts Commission Northern Piedmont Community Foundation Portsmouth Museum and Fine Arts Commission R.E.B. Foundation Richard S. Reynolds Foundation Suffolk Fine Arts Commission Virginia Beach Arts & Humanities Commission Virginia Commission for the Arts Wells Fargo Foundation Williamsburg Area Arts Commission York County Arts Commission Virginia Opera extends sincere thanks to the Woodlands Retirement Community (Fairfax, VA) as the inaugural donor to Virginia Opera’s newest funding initiative, Adopt-A-School, by which corporate, foundation, group and individual donors can help share the magic and beauty of live opera with underserved children. For more information, contact Cecelia Schieve at [email protected] 1 Table of Contents Premiere 2 Cast of Characters 2 Plot Synopsis and Musical Highlights 3 Historical Background 6 A Short History of Opera 10 The Operatic Voice 12 Opera Production 14 Discussion Questions 16 2 Premiere Teatro alla Scala, Milan, on 17 February 1904 (revised version Brescia, Teatro -

From Madame Butterfly to Miss Saigon: One Hundred Years of Popular Orientalism

11/4/2017 EBSCOhost Record: 1 From Madame Butterfly to Miss Saigon: One hundred years of popular orientalism. By: Degabriele, Maria. Critical Arts: A South-North Journal of Cultural & Media Studies. 1996, Vol. 10 Issue 2, p105. 14p. Abstract: Focuses on the popular orientalist myth of the opera `Madame Butterfly.' Variations of the play; Proliferation of the story, music and images with the advent of mass media technology; Plot of Madame Butterfly; Portrayal of the Western man's sovereignty to enter Asia. (AN: 9701226250) Database: Academic Search Complete FROM MADAME BUTTERFLY TO MISS SAIGON: ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF POPULAR ORIENTALISM In the last hundred years the story of Madame Butterfly has been endlessly repeated and elaborated. As such, the Madame Butterfly myth has become a key orientalist intertext, beginning with Pierre Loti's Madame Chrysantheme (1887) as the original nineteenth century text and ending provisionally with Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schonberg's Miss Saigon (1989) as the most contemporary text of the Madame Butterfly narrative. The first text inspired subsequent texts, right through to today, when its basic premises are mostly being unquestioningly re-performed. Only recently have there been some texts that have seriously challenged and undermined the Madame Butterfly myth, signalling that although representation often depends on repetition, it also reflects change. The most significant of these texts are M. Butterfly (1992) by David Henry Hwang and David Cronenberg's movie of the same name (1993), for which Hwang wrote the screenplay and which he co-produced, and Dennis O'Rourke's film The Good Woman of Bangkok (1991), described by Chris Berry (1994) as "documentary fiction". -

Madame Chrysanthème As an Item of Nineteenth-Century French

MADAME CHRYSANTHEME AS AN ITEM OF NINETEENTH-CENTURY FRENCH JAPONAISERIE Heather McKenzie A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Canterbury 2004 II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS How did I meet you? I don't know A messenger sent me ill a tropical storm. You were there in the winter, Moonlight on the snow, And on Lillypond Lane When the weather was warm. Bob Dylan Any experience is coloured by the people with whom we share it. My Ph.D. years were brightened by the following kaleidoscope of people: · .. my family who have supported me in whatever I have chosen to do: Andrew for being a dependable brother; Fay, the best nan with her sparkle and baking talents; John, a generous and wise father; Mark, a like-minded companion and source of fine port; and Rowena for being an encouraging mother and friend. · .. Ken Strongman, mentor and friend for absolutely anything. · .. Greg my best friend, from across the corridor or from across the Pacific: a true amigo para siempre . ... Maureen Heffernan, who I enjoy knowing in a number of contexts: out running, in the consulate office, or across the table over dinner. ... Dave Matheson, a helpful, unassuming, and quietly supportive friend who appeared at just the right time. · .. Andrew Stockley whose friendship percolated through the latter stages of my Ph.D. life. '" Chris Wyeth, for friendship and support given over a long period of time. '" Nick, Kathryn, Steve, Rachel, Glen, and Natasha for their laughter and companionship. '" Sayoko Yabe for her energy and generosity.