Marlow Common Clay Pits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weekly List of Planning Applications

Weekly List of Planning Applications Planning & Sustainability 14 March 2019 1 10/2019 Link to Public Access NOTE: To be able to comment on an application you will need to register. Wycombe District Council WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED 13.03.19 19/05272/FUL Received on 21.02.19 Target Date for Determination: 18.04.2019 Other Auth. Ref: AIDAN LYNCH Location : 152 Cressex Road High Wycombe Buckinghamshire HP12 4UA Description : Householder application for single storey rear extension Applicant : Mr & Mrs Edworthy 152 Cressex Road High Wycombe Buckinghamshire HP12 4UA Agent : Al3d Unit 1 The Hall High Street Tetsworth OX9 7BP Parish : High Wycombe Town Unparished Ward : Abbey Officer : Jackie Sabatini Level : Delegated Decision 19/05343/PNP3O Received on 05.03.19 Target Date for Determination: 30.04.2019 Other Auth. Ref: MR KEVIN SCOTT Location : Regal House 4 - 6 Station Road Marlow Buckinghamshire SL7 1NB Description : Prior notification application (Part 3, Class O) for change of use of existing building falling within Class B1(a) (offices) to Class C3 (dwellinghouses) to create 15 residential dwellings Applicant : Sorbon Estates Ltd C/o The Agent Agent : Kevin Scott Consultancy Ltd Sentinel House Ancells Business Park Harvest Crescent Fleet Hampshire Parish : Marlow Town Council Ward : Marlow South And East Officer : Emma Crotty Level : Delegated Decision 2 19/05351/FUL Received on 26.02.19 Target Date for Determination: 23.04.2019 Other Auth. Ref: MR A B JACKSON Location : 6 Hillfield Close High Wycombe Buckinghamshire -

Lca 26.1 Thames Floodplain

LCA 26.1 THAMES FLOODPLAIN LCA in Context LCA 26.1 THAMES FLOODPLAIN KEY CHARACTERISTICS • A flat, low lying floodplain, with very slight local topographic variation, underlain by a mix of alluvium, head and gravel formations, with free draining soils. • Fields of arable farmland pasture and rough grazing are divided by wooden post and rail fencing and hedgerows. • The River Thames runs along the southern boundary. Fields near the river are liable to flooding and there are areas of water meadow. • Willow pollards along the Thames and scattered or clumped trees along field boundaries. Woodland cover is sparse. • Varied ecology with gravel-pit lakes at Spade Oak/ Little Marlow and SSSIs including wet woodland and wet meadows. • The town of Marlow has a historic core and small villages such as Little Marlow and Medmenham have a historic character. More recent residential development at Bourne End and on the edges of Marlow. • A mixed field pattern with enclosures from irregular pre 18th century (regular, irregular and co-axial) though regular parliamentary enclosures to 20th century extended fields and horse paddocks. • A range of historic and archaeological features, including parkland at Fawley Court and Harleyford Manor, Medmenham Manor, Neolitihic and Bronze Age finds at Low Grounds and historic locks. • Cut by the busy A4155 and the A404 with rural roads leading down to the Thames and up the valley sides to the north. • The low-lying, flat and open landscape allows for some long views and panoramic vistas particularly north towards the higher sloping topography of the lower dip slope. • Some pockets of tranquillity and calm associated with areas of water and parkland, away from roads and settlement. -

BUCKINGHAMSHIRE POSSE COMITATUS 1798 the Posse Comitatus, P

THE BUCKINGHAMSHIRE POSSE COMITATUS 1798 The Posse Comitatus, p. 632 THE BUCKINGHAMSHIRE POSSE COMITATUS 1798 IAN F. W. BECKETT BUCKINGHAMSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY No. 22 MCMLXXXV Copyright ~,' 1985 by the Buckinghamshire Record Society ISBN 0 801198 18 8 This volume is dedicated to Professor A. C. Chibnall TYPESET BY QUADRASET LIMITED, MIDSOMER NORTON, BATH, AVON PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY ANTONY ROWE LIMITED, CHIPPENHAM, WILTSHIRE FOR THE BUCKINGHAMSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY CONTENTS Acknowledgments p,'lge vi Abbreviations vi Introduction vii Tables 1 Variations in the Totals for the Buckinghamshire Posse Comitatus xxi 2 Totals for Each Hundred xxi 3-26 List of Occupations or Status xxii 27 Occupational Totals xxvi 28 The 1801 Census xxvii Note on Editorial Method xxviii Glossary xxviii THE POSSE COMITATUS 1 Appendixes 1 Surviving Partial Returns for Other Counties 363 2 A Note on Local Military Records 365 Index of Names 369 Index of Places 435 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The editor gratefully acknowledges the considerable assistance of Mr Hugh Hanley and his staff at the Buckinghamshire County Record Office in the preparation of this edition of the Posse Comitatus for publication. Mr Hanley was also kind enough to make a number of valuable suggestions on the first draft of the introduction which also benefited from the ideas (albeit on their part unknowingly) of Dr J. Broad of the North East London Polytechnic and Dr D. R. Mills of the Open University whose lectures on Bucks village society at Stowe School in April 1982 proved immensely illuminating. None of the above, of course, bear any responsibility for any errors of interpretation on my part. -

Election of Parish Councillors for the Parishes Listed Below (Wycombe Area)

NOTICE OF ELECTION Buckinghamshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for the Parishes listed below (Wycombe Area) Number of Parish Parishes Councillors to be elected Election of councillors to Bledlow cum Saunderton Parish 3 Council for Bledlow Ridge ward Election of councillors to Bledlow cum Saunderton Parish 3 Council for Bledlow ward Election of councillors to Bledlow cum Saunderton Parish 3 Council for Saunderton ward Election of councillors to Bradenham Parish Council 7 Election of councillors to Chepping Wycombe Parish Council 7 for Flackwell Heath ward Election of councillors to Chepping Wycombe Parish Council 5 for Loundwater ward Election of councillors to Chepping Wycombe Parish Council 5 for Tylers Green ward Election of councillors to Downley Parish Council 11 Election of councillors to Ellesborough Parish Council 7 Election of councillors to Great & Little Hampden Parish 5 Council Election of councillors to Great & Little Kimble-Cum-Marsh 7 Parish Council Election of councillors to Great Marlow Parish Council 8 Election of councillors to Hambleden Parish Council for 5 Hambleden North ward Election of councillors to Hambleden Parish Council for 4 Hambleden South ward Election of councillors to Hazlemere Parish Council for 6 Hazlemere North ward Election of councillors to Hazlemere Parish Council for 6 Hazlemere South ward Election of councillors to Hughenden Parish Council for Great 3 Kingshill ward Election of councillors to Hughenden Parish Council for 4 Hughenden Valley ward Election of councillors to Hughenden Parish -

800/850 High Wycombe

High Wycombe - Marlow - Henley - Reading 800/850 Monday to Friday From: 4 September 2016 Service number: 800 850 800 850 850 800 800 800 80X 850 850 800 800 800 Notes: sch sch Nsch sch sch Nsch sch Nsch sch High Wycombe Bus Station, Gate E 0525 0600 0620 0640 0705 0725 0730 0734 0735 0740 0748 0805 0813 0835 Cressex Road, Marlow Road 0532 0607 0628 0648 0713 0734 0740 0742 | 0751 0756 0817 0821 0847 Marlow, Wiltshire Road 0538 0613 0634 0654 0719 0740 0746 0749 | 0758 0803 0825 0828 0855 Little Marlow Road ||||||||0745 ||||| Marlow, West Street 0543 0618 0640 0700 0726 0747 0754 0756 0752 0806 0810 0835 0835 0903 Medmenham, Dog and Badger 0550 0625 0647 0707 0733 0754 0801 0803 0759 0814 0817 0842 0842 0910 Henley, Hart Street ARR 0600 0635 0658 0719 0746 0809 0815 0815 0815 0832 0830 0900 0855 0925 Henley, Hart Street DEP 0601 0636 0701 0721 0748 0818 0818 0835 0835 0905 0905 0930 Wargrave, Greyhound | 0646 | 0731 0758 | | 0845 0845 | | | Twyford, Arnside Close | 0649 | 0734 0802 | | 0849 0849 | | | Twyford, High Street | 0653 | 0739 0809 | | 0856 0856 | | | Sonning, Halt | 0658 | 0746 0816 | | 0903 0903 | | | Woodley, Shepherds Hill Top | 0700 | 0749 0819 | | 0906 0906 | | | Reading Cemetery Junction | 0705 | 0756 0827 | | 0911 0911 | | | Shiplake, Station Road 0609 | 0709 | | 0830 0827 | | 0914 0914 0939 Binfield Heath, Heathfield Close 0615 | 0715 | | 0837 0834 | | 0921 0921 0946 Dunsden Green 0617 | 0717 | | 0839 0836 | | 0923 0923 0948 Caversham Park 0620 | 0720 | | 0843 0839 | | 0926 0926 0951 Reading Station, North Interchange -

Illustrated History of Early Buckinghamshire

Volume 8 Issue 1, February 2010 www.archaeologyinmarlow.org.uk ArchaeologyArchaeology inin MarlowMarlowNewsletter New discovery in St Albans Not far from the entrance to Verulamium Park a “treasure Forthcoming AiM Events trove” of Mesolithic finds and Roman architecture has Thursday 25 February 8 p.m. just been discovered during an archaeological excavation Chairmaking in the Chilterns before a planning application for a new leisure centre. Garden Room, Liston Hall, Marlow: A talk by the Twelve trenches, including two joined pairs were dug in Curator of Wycombe Museum, Dr Catherine Grigg, January and finds already include a probable Roman mill, who has made a special study of this local craft. Find and prehistoric flints. out about traditional chair making, including how to tell The most important if a Windsor chair was made locally. discovery is a two-phase Members £2.50, non members £3.50 Roman building, but this seems Thursday 25 March 8 p.m. to have been at Iron Age Hillforts of Marlow and Taplow, least partially Garden Room, Liston Hall, Marlow: A talk by d e m o l i s h e d Dr Tubb – he will discuss recent discoveries during the Roman regarding Danesfield Hillfort, Medmenham or medieval period. Hillford and Taplow Court. Dr Tubb is a Preliminary dating landscape archaeologist, a tutor at Bristol suggests it was OK, I admit it - the photos are not the new discovery University and teaches continuing education built in the second to or even representative of it - but they were all I had courses. See page four for more details third century AD. -

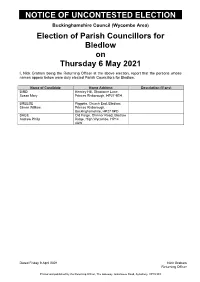

Wyc Parish Uncontested Election Notice 2021

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Buckinghamshire Council (Wycombe Area) Election of Parish Councillors for Bledlow on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Nick Graham being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Bledlow. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BIRD Hemley Hill, Shootacre Lane, Susan Mary Princes Risborough, HP27 9EH BREESE Piggotts, Church End, Bledlow, Simon William Princes Risborough, Buckinghamshire, HP27 9PD SAGE Old Forge, Chinnor Road, Bledlow Andrew Philip Ridge, High Wycombe, HP14 4AW Dated Friday 9 April 2021 Nick Graham Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, The Gateway, Gatehouse Road, Aylesbury, HP19 8FF NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Buckinghamshire Council (Wycombe Area) Election of Parish Councillors for Bourne End on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Nick Graham being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Bourne End. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) APPLEYARD Wooburn Lodge, Grange Drive Mike (Off Brookbank), Wooburn, Bucks, HP10 0QB BINGHAM 7 Jeffries Court, Bourne End, SL8 Timothy Rory 5DY BLAZEY Wyvern, Cores End Road, Bourne Ian Gavin End, Buckinghamshire, SL8 5HR BLAZEY Wyevern, Cores End Road, Miriam Bourne End, Buckinghamshire, SL8 5HR CHALMERS Ivybridge, The Drive, Bourne End, Ben Buckinghamshire, SL8 5RE COBDEN (address in Buckinghamshire) Andrew George MARSHALL Broome House, -

Buckinghamshire Council Tax 2020/21

Buckinghamshire council tax 2020/21 As required by Section 38(2) of the Local Government Finance Act 1992 notice is hereby given that at its meeting on 27/02/2020 Buckinghamshire Council, in accordance with the provisions of Section 30 of the LGFA 1992, set the following amounts of council tax for each of the areas and each of the valuation bands shown below. In each case the amount includes an element for precepts issued to the Council by the Police and Crime Commissioner for Thames Valley, the Bucks and Milton Keynes Fire Authority and the relevant Parish or Town Council. Parish Band A Band B Band C Band D Band E Band F Band G Band H Addington £1,218.59 £1,421.69 £1,624.78 £1,827.88 £2,234.07 £2,640.27 £3,046.47 £3,655.76 Adstock £1,265.60 £1,476.53 £1,687.46 £1,898.39 £2,320.25 £2,742.12 £3,163.99 £3,796.78 Akeley £1,264.84 £1,475.64 £1,686.44 £1,897.25 £2,318.86 £2,740.47 £3,162.09 £3,794.50 Amersham £1,290.28 £1,505.32 £1,720.36 £1,935.41 £2,365.50 £2,795.59 £3,225.69 £3,870.82 Ashendon £1,300.90 £1,517.72 £1,734.53 £1,951.35 £2,384.98 £2,818.62 £3,252.25 £3,902.70 Ashley Green £1,244.65 £1,452.09 £1,659.53 £1,866.97 £2,281.85 £2,696.73 £3,111.62 £3,733.94 Aston Abbotts £1,280.92 £1,494.41 £1,707.89 £1,921.38 £2,348.35 £2,775.33 £3,202.30 £3,842.76 Aston Clinton £1,302.27 £1,519.32 £1,736.35 £1,953.40 £2,387.48 £2,821.58 £3,255.67 £3,906.80 Aston Sandford £1,218.59 £1,421.69 £1,624.78 £1,827.88 £2,234.07 £2,640.27 £3,046.47 £3,655.76 Aylesbury Town £1,292.98 £1,508.48 £1,723.97 £1,939.47 £2,370.46 £2,801.46 £3,232.45 £3,878.94 Barton -

Bands and Charges 2021 to 2022

£ £ £ £ £ £ £ £ Parish / Town Band A Band B Band C Band D Band E Band F Band G Band H Area Addington 1,270.58 1,482.34 1,694.11 1,905.87 2,329.40 2,752.92 3,176.45 3,811.74 Adstock 1,317.90 1,537.55 1,757.20 1,976.85 2,416.15 2,855.45 3,294.75 3,953.70 Akeley 1,321.32 1,541.54 1,761.76 1,981.98 2,422.42 2,862.86 3,303.30 3,963.96 Amersham 1,344.61 1,568.71 1,792.83 2,016.92 2,465.13 2,913.33 3,361.53 4,033.84 Ashendon 1,351.52 1,576.77 1,802.03 2,027.28 2,477.79 2,928.29 3,378.80 4,054.56 Ashley Green 1,298.28 1,514.66 1,731.05 1,947.42 2,380.18 2,812.94 3,245.70 3,894.84 Aston Abbotts 1,333.13 1,555.32 1,777.52 1,999.70 2,444.08 2,888.46 3,332.83 3,999.40 Aston Clinton 1,353.09 1,578.60 1,804.12 2,029.63 2,480.66 2,931.68 3,382.72 4,059.26 Aston Sandford 1,270.58 1,482.34 1,694.11 1,905.87 2,329.40 2,752.92 3,176.45 3,811.74 Aylesbury 1,346.88 1,571.36 1,795.84 2,020.32 2,469.28 2,918.24 3,367.20 4,040.64 Town Barton 1,270.58 1,482.34 1,694.11 1,905.87 2,329.40 2,752.92 3,176.45 3,811.74 Hartshorn Beachampton 1,281.64 1,495.24 1,708.86 1,922.46 2,349.68 2,776.88 3,204.10 3,844.92 Beaconsfield 1,313.56 1,532.48 1,751.42 1,970.34 2,408.20 2,846.04 3,283.90 3,940.68 Berryfields 1,314.87 1,534.02 1,753.17 1,972.32 2,410.62 2,848.90 3,287.19 3,944.64 Biddlesden 1,270.58 1,482.34 1,694.11 1,905.87 2,329.40 2,752.92 3,176.45 3,811.74 Bierton 1,298.19 1,514.56 1,730.93 1,947.29 2,380.02 2,812.75 3,245.48 3,894.58 Bledlow-cum- 1,280.60 1,494.03 1,707.46 1,920.89 2,347.76 2,774.62 3,201.48 3,841.78 Saunderton Boarstall 1,280.83 1,494.29 1,707.77 -

Valley Slope

LCT 21 VALLEY SLOPE Constituent LCAs LCA 21.1 Thames LCA LCA XX LCT 21 VALLEY SLOPE KEY CHARACTERISTICS • Transitional, gently sloping valley side, gradually descending from higher ground to floodplain. A sloping and gently rolling topography, composed of chalk and river terrace deposits. • Fields of arable, pasture and rough grazing, which are delineated by a network of hedgerows and trees. • Large blocks of woodland located along upper slopes. Smaller areas of woodland are interlocked with farmland. Some pockets of calcareous grassland. • Settlement comprises town and village edges, small hamlets and scattered farmsteads, with a mix of historic character and modern infilling. • Archaeological features and historic parkland scattered across this landscape. • Some busy roads cut through, elsewhere, small rural roads and lanes, often enclosed by trees and hedgerows and sunken in places, cross the slopes. • The open, sloping landform allows long views out across lower floodplain topography. • Away from busy roads and settlement edges, enclosed lanes, farmland and woodland create a rural and peaceful character. Land Use Consultants 137 LCA 21.1 THAMES VALLEY SLOPE LCA in Context LCA 21.1 THAMES VALLEY SLOPE KEY CHARACTERISTICS • Transitional, gently sloping valley side, gradually descending southwards from the higher rolling farmland to the Thames floodplain. • Geology of exposed chalk combined with Thames River Terrace Deposits, gives rise to a sloping and gently rolling topography. • Fields of arable cultivation, pasture and rough grazing delineated by a network of hedgerows and trees. • Large blocks of woodland (commonly beech and yew) are located along the upper slopes, much of which is ancient woodland. Smaller areas of woodland are interlocked with farmland. -

The Boundary Committee for England Periodic Electoral

THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND KEY "This map is reproduced from the OS map by The Electoral Commission EXISTING DISTRICT BOUNDARY with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. PROPOSED ELECTORAL DIVISION BOUNDARY Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. EXISTING WARD BOUNDARY Licence Number: GD03114G" WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH ELECTORAL DIVISION BOUNDARY PERIODIC ELECTORAL REVIEW OF BUCKINGHAMSHIRE EXISTING PARISH BOUNDARY PARISH WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH OTHER BOUNDARIES PROPOSED ELECTORAL DIVISION NAME ABBEY ELECTORAL DIVISION Only Parishes whose Warding has been altered Final Recommendations for Electoral Division Boundaries September 2004 by these Recommendations have been coloured. Sheet 2 of 3 MAP 1 Wycombe District. Abbey, Booker, Cressex and Sands, Downley, Disraeli, Oakridge and Castlefield, Stokenchurch,Radnage and West Wycombe divisions DOWNLEY AND PLOMER HILL WARD DOWNLEY CP DISRAELI WARD W ES T W CHILTERN RISE WARD YC OM BE RO STOKENCHURCH, RADNAGE AND WEST WYCOMBE AD WEST WYCOMBE CP ELECTORAL DIVISION (44) Sands County West Wycombe Park Middle School Desborough Recreation Ground G E R AN O L V E DG E I ER R OW O T A D D A O R K R DASHWOOD AVENUE A P H G U O SANDS WARD R O B S E D DOWNLEY, DISRAELI, OAKRIDGE AND CASTLEFIELD Sands Wood ELECTORAL DIVISION Castlefield Wood CO PY (38) GR OU ND LA NE BOOKER, CRESSEX AND SANDS OAKRIDGE AND CASTLEFIELD WARD ELECTORAL DIVISION (36) SANDS E U N E PL V UM A ER D R N O A A L D T U R D A O R N O T G Sands IN Scale : 1cm = .02358km R Industrial Estate R A Grid interval is 1km C 193,000m ABBEY 484,000m ELECTORAL DIVISION SU89SW (34) Round Wood ABBEY WARD K L A W D L E I F T S E W MAP 2 Wycombe District. -

Hambleden Valley Churches

Hambleden VALLEY 2013 December Group Magazine Group Serving the Communities of Fawley Fingest Hambleden with Frieth and Skirmett Medmenham Turville HAMBLEDEN VALLEY £1.00 £1.00Aug 2020 In This Issue Group Letter 1 Group Notes and News 4 Wildlife 8 Hambleden 14 Sunday Services 15 From the Registers 15 Frieth 18 Fingest 21 Classified Advertisements 24 Church and Village Activities and Contacts 26 Weekday Services Wednesday 10am Zoom Daily Prayer Emergencies: If you are unable to contact the Group Priests, please get in touch with your churchwarden. All contributions are welcome, to the Editor, Penny McLeish [email protected] (please note change of email address) 3 Abbey Cottages, Ferry Lane, Medmenham SL7 2HB Telephone 01491 571288 Please keep articles within 350 words. Copy deadline is 15th of the month. Printed by Higgs and Co., Henley. Tel. 01491 419429 Cover: The road less travelled, photo Emily McLeish. This is slightly outside the Valley, do you know where it is? Answer page 22 . This page: Dark Mullein This page 22 . itis? Answer know where do you Valley, the slightly outside is This Emily McLeish. photo less travelled, The road Cover: 1 GROUP LETTER Continuing our result great difficulty in fulfilling their series of Group core responsibility under Canon Law Letters written “to encourage the parishioners in the by some of the practice of true religion” many people But isn’t it true that home is where the who support heart is? “Normal” life and activities have the Hambleden been put on hold and we have had no Valley Churches, I have invited Jill choice but to look outside the physical Dean - Fingest familiarity of our parish churches for a churchwarden community with whom to share prayer and former lay chair - to write this and worship God.