Small Market Radio: a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

Radio Stations in Michigan Radio Stations 301 W

1044 RADIO STATIONS IN MICHIGAN Station Frequency Address Phone Licensee/Group Owner President/Manager CHAPTE ADA WJNZ 1680 kHz 3777 44th St. S.E., Kentwood (49512) (616) 656-0586 Goodrich Radio Marketing, Inc. Mike St. Cyr, gen. mgr. & v.p. sales RX• ADRIAN WABJ(AM) 1490 kHz 121 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 265-1500 Licensee: Friends Communication Bob Elliot, chmn. & pres. GENERAL INFORMATION / STATISTICS of Michigan, Inc. Group owner: Friends Communications WQTE(FM) 95.3 MHz 121 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 265-9500 Co-owned with WABJ(AM) WLEN(FM) 103.9 MHz Box 687, 242 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 263-1039 Lenawee Broadcasting Co. Julie M. Koehn, pres. & gen. mgr. WVAC(FM)* 107.9 MHz Adrian College, 110 S. Madison St. (49221) (517) 265-5161, Adrian College Board of Trustees Steven Shehan, gen. mgr. ext. 4540; (517) 264-3141 ALBION WUFN(FM)* 96.7 MHz 13799 Donovan Rd. (49224) (517) 531-4478 Family Life Broadcasting System Randy Carlson, pres. WWKN(FM) 104.9 MHz 390 Golden Ave., Battle Creek (49015); (616) 963-5555 Licensee: Capstar TX L.P. Jack McDevitt, gen. mgr. 111 W. Michigan, Marshall (49068) ALLEGAN WZUU(FM) 92.3 MHz Box 80, 706 E. Allegan St., Otsego (49078) (616) 673-3131; Forum Communications, Inc. Robert Brink, pres. & gen. mgr. (616) 343-3200 ALLENDALE WGVU(FM)* 88.5 MHz Grand Valley State University, (616) 771-6666; Board of Control of Michael Walenta, gen. mgr. 301 W. Fulton, (800) 442-2771 Grand Valley State University Grand Rapids (49504-6492) ALMA WFYC(AM) 1280 kHz Box 669, 5310 N. -

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows As of 01-01-2003

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows as of 01-01-2003 $64,000 Question, The 10-2-4 Ranch 10-2-4 Time 1340 Club 150th Anniversary Of The Inauguration Of George Washington, The 176 Keys, 20 Fingers 1812 Overture, The 1929 Wishing You A Merry Christmas 1933 Musical Revue 1936 In Review 1937 In Review 1937 Shakespeare Festival 1939 In Review 1940 In Review 1941 In Review 1942 In Revue 1943 In Review 1944 In Review 1944 March Of Dimes Campaign, The 1945 Christmas Seal Campaign 1945 In Review 1946 In Review 1946 March Of Dimes, The 1947 March Of Dimes Campaign 1947 March Of Dimes, The 1948 Christmas Seal Party 1948 March Of Dimes Show, The 1948 March Of Dimes, The 1949 March Of Dimes, The 1949 Savings Bond Show 1950 March Of Dimes 1950 March Of Dimes, The 1951 March Of Dimes 1951 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1951 March Of Dimes On The Air, The 1951 Packard Radio Spots 1952 Heart Fund, The 1953 Heart Fund, The 1953 March Of Dimes On The Air 1954 Heart Fund, The 1954 March Of Dimes 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air With The Fabulous Dorseys, The 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1954 March Of Dimes On The Air 1955 March Of Dimes 1955 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1955 March Of Dimes, The 1955 Pennsylvania Cancer Crusade, The 1956 Easter Seal Parade Of Stars 1956 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 Heart Fund, The 1957 March Of Dimes Galaxy Of Stars, The 1957 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 March Of Dimes Presents The One and Only Judy, The 1958 March Of Dimes Carousel, The 1958 March Of Dimes Star Carousel, The 1959 Cancer Crusade Musical Interludes 1960 Cancer Crusade 1960: Jiminy Cricket! 1962 Cancer Crusade 1962: A TV Album 1963: A TV Album 1968: Up Against The Establishment 1969 Ford...It's The Going Thing 1969...A Record Of The Year 1973: A Television Album 1974: A Television Album 1975: The World Turned Upside Down 1976-1977. -

12 Media.Qxd

Media Information Sports Information Staff The 2005-06 University of Tennessee basketball media Media Luncheons guide is published primarily as a source of information Beginning in January, Bruce Pearl will host a weekly Bud Ford for members of the media. Requests for additional infor- media luncheon in the Arena Dining area at Thompson- Associate Athletic mation, interviews and photographs should be directed Boling Arena. A schedule for the luncheons will be Director/Sports Information to Craig Pinkerton, associate SID, P.O. Box 15016, announced at a later date. A 39-year veteran of his pro- Knoxville, TN 37901. fession, University of Tennessee Coach Interviews graduate Bud Ford was promoted in April 2000 to the position of Media Credentials Media may request interviews with Bruce Pearl and his associate athletics director for Requests for media credentials should be submitted in staff by calling the SID Office (865) 974-1212. sports information. He was elected to the CoSIDA Hall writing well in advance to Craig Pinkerton, associate of Fame in May 2001. SID. You may fax your requests to (865) 974-1269 at Player Interviews Ford began his career as a part-time employee in the least one week in advance of the game you plan to cover. All requests for player interviews should be directed to Vols publicity office while he completed undergraduate Credentials will be left at the Media Will Call entrance Craig Pinkerton, associate SID. Please make your studies. He then pioneered the position of full-time assis- on the west end of Thompson-Boling Arena. Only requests at least 24 hours in advance. -

Media Outlet Results

Media Outlet Results Outlet Name Outlet City Outlet State Outlet TypeOutlet Website Outlet E-mail Outlet Phone Number Outlet Circulation KeywordAudience OutletRelevance Source Carthage Carthage TN News http://cartha news@cart (615) 735-1110 5,600 100 S Courier, The paper gecourier.co hagecourier. , m/ com com munit y Herald-Citizen Cookeville TN News http://www.h editor@hera (931) 526-9715 9,945 100 S paper erald- ld- , citizen.com citizen.com com munit y Jackson County Gainesboro TN News http://www.li sentinel@liv (931) 268-9725 3,300 100 S Sentinel paper vingstonent ingstonenter , erprise.net prise.net com munit y Livingston Livingston TN News http://www.li stories@livi (931) 823-1274 5,000 100 S Enterprise, The paper vingstonent ngstonenter , erprise.net prise.net com munit y Middle Smithville TN News http://www. editor@mid (615) 597-2100 3,000 100 S Tennessee paper middletntim dletntimes.c Times, The , es.com/ om com munit y Page: 1 09/27/2011 Media Outlet Results Outlet Name Outlet City Outlet State Outlet TypeOutlet Website Outlet E-mail Outlet Phone Number Outlet Circulation KeywordAudience OutletRelevance Source Overton County Livingston TN News http://www.o news@over (931) 823-6485 5,550 100 S News paper vertoncount toncountyne , ynews.com ws.com com munit y Smithville Smithville TN News http://www.s sreview@dt (615) 597-5485 4,500 100 S Review, The paper mithvillerevi ccom.net , ew.com com munit y UC Daily Cookeville TN Onlin http://www.u news@ucda (931) 250-3382 0 100 S News.com e, cdailynews. -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

New Combo Set to Go Chesterfield Program Bags Peggy Lee For

NEWS FROM HOLLYWOOD VOL. 4, NO. 4 APRIL, 1946 Butterfield9» New Combo Set to Go gILLY BUTTERFIELD’S long- awaited band is fin a lly m aterializ ing. The pudgy trum peter, long featured w ith Am erica’s top bands as a sideman and also on Capitol records with his own studio crews, is g woodshedding his 1946 agggregation in l( New York and bookings are being set d up for a debut within 30 days. n Managing the B. B. outfit will be n Ceorge Moffett, who has guided Hal i McIntyre for several years. o An Ohio musician, Billy first attract- | ed attention as a member of the old Bob Crosby band in the m iddle 1930’s. Charlie Spivak and Yank Lawson held ¡down the other tru m p e t chairs fo r sev eral months together. Later, with Artie Shaw, Benny Goodman and Les Brown, Billy recorded and was regularly fe a BLEND is the word — at least that’s what the Dinning Sisters achieve tured. Recently, since his arm y dis when they platter for Capitol with Paul Weston’s studio orchestra backing charge, he has been playing New Y ork their efforts. The sisters include, left to right, Ginger, Lou and Jean. They radio shows and jam m ing, on Monday were recently starred in the floorshow at the Hollywood Trocadero. All three nights, at Ed Condon’s Greenwich V il hail from Oklahoma. lage bistro with others of the Nixieland school. Billy now makes his home in Great Neck, L. I. -

Hisbed Restaurant, Has in the Proprietorship of Messrs

EEK'S LETE TELEVISION PROGRAMS THE UNDAY NORTH JERSEY'S ONLY WEEKLY PICTORIAL MAGAZINE :: .. • .•,.•':" .::: •:'•'••:L•.:½•..:';•::,,. .-..:.-.Y*:•-:....:-:..-'•::-•...:' :'.•:... 5:( ;.;•....:::;v .,..k' .'•, .•ß ß ,' '-':"'.'. ,-"•-,.,.•! ..... ;• ß •' ' -"•t- ,,:'-,.-'F-•½ ' .-.'": .....................,;•-- '• :t" ---., ß ß •'.-'• ,t•; ;•'•"• ' :.. .............. & .., , ':'•;•'-:.-. '?? Town and Country .... ..• . ß :.Z.;'•:....•. -.: --, ,.... Dining .......::., ..•.:: •..,.,;;./.,..'. ,...:.,...½,.:. '•.,, .•.., .':"•,.:...':•:;••.'.'.,t.... '-'..:'...& . .:•,,..•.-;• ,. , ...... .... : .. ..•....• . .½ , - ,• .,..?•,, ß There's Only One .•, Stengel 2,,, .,, ,. ., ,.,.. :. ß ß' ;' ,,: e:.. • , . , ! 's Pure Fact... .• •- ,%. .,.•, ;.. .. ß .?. ß ;.. , .,.:. .... .. • .... ,,.,.•?')!.•.?.•..,:;..;½.: ';::. .;•:.,. .. ,,• ....:.,•,...: ß if, : ::. .?.. !' ,.• , ,• ß •.' .,,,•,,•, "'½ • '- t•, ..' How Close Will The ",..½..;,,..,,*.t:':" " '"'"' ''];i:(, ß .,. •:',-,, •,:,,,,.,-,.,, ';;':"""* .,..,.,.' .. ;' , •, ½.:.. Presidential ...... • ",. .•,, .• ..... ß ß • , ,.; '•,• (. Election Be? ß , .. ,?.½:,ß -, . , .. .- ,• .-..•-,.;, ?:;;:•., ,, ,.ß • . •,,. ,• .. ,• ' ' ,,.,•' }:,a', •','"• •' -,•'•..:.,.. .'•,it...,:' •. "''? ' ... ......:,... .:. ,• * :::,•'. ,' .;...... ,•.... ,.,•.>• •, ...,........:...-.... ........ ;:;'].:.:" .. ., . .,, .•.. .... .... :: .. ... ß . .. •.....,.. ..... ß , • .•. ...•. , , .... .... ß . :. Complete , .....,..... ½.t ': .... :',.'.' .:- ....•... ..... ..• .... ß Short Story ß . .. :: -..,•/iia,- -

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-2-210112-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 01/12/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000120864 Construction DRT WVIZ 18753 Main 566.0 Cleveland, OH IDEASTREAM 01/08/2021 Granted Permit From: To: 0000115558 Renewal of FM WNBY- 20379 Main 93.9 NEWBERRY, MI SOVEREIGN 01/08/2021 Pending License FM COMMUNICATIONS, LLC From: To: 0000124049 License To LPT K14TF-D 47721 Main 14 OPELOUSAS, LA DIGITAL NETWORKS- 01/08/2021 Granted Cover SOUTHEAST, LLC From: To: 0000115550 Renewal of FM WYSS 977 Main 99.5 SAULT STE. SOVEREIGN 01/08/2021 Pending License MARIE, MI COMMUNICATIONS, LLC From: To: 0000114878 Renewal of FM WCHY 189567 Main 97.7 CHEBOYGAN, MICHIGAN 01/08/2021 Pending License MI BROADCASTERS LLC From: To: 0000113040 Renewal of FM WMOR- 73279 Main 106.1 MOREHEAD, KY MORGAN COUNTY 01/08/2021 Pending License FM INDUSTRIES, INC. From: To: Page 1 of 8 REPORT NO. PN-2-210112-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 01/12/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000122035 License To LPD KAVC-LD 68077 Main 674.0 Denver, CO DIGITAL NETWORKS- 01/08/2021 Granted Cover MIDWEST, LLC From: To: 0000092394 Renewal of AM WUFE 73 Main 1260.0 BAXLEY, GA SOUTH GEORGIA 01/08/2021 Pending License BROADCASTERS, Amendment INC. -

Exhibit 2181

Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 4 Electronically Filed Docket: 19-CRB-0005-WR (2021-2025) Filing Date: 08/24/2020 10:54:36 AM EDT NAB Trial Ex. 2181.1 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 2 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.2 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 3 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.3 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 4 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.4 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 132 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 1 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.5 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 133 Filed 04/15/20 Page 1 of 4 ATARA MILLER Partner 55 Hudson Yards | New York, NY 10001-2163 T: 212.530.5421 [email protected] | milbank.com April 15, 2020 VIA ECF Honorable Louis L. Stanton Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse 500 Pearl St. New York, NY 10007-1312 Re: Radio Music License Comm., Inc. v. Broad. Music, Inc., 18 Civ. 4420 (LLS) Dear Judge Stanton: We write on behalf of Respondent Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) to update the Court on the status of BMI’s efforts to implement its agreement with the Radio Music License Committee, Inc. (“RMLC”) and to request that the Court unseal the Exhibits attached to the Order (see Dkt. -

Rutterfield W Ill Record for Capitol Capitol Records Has Signed Trumpet-Ace Billy Butterfield to an Exclusive Recording Contract

NEWS FROM HOLLYWOOD i ! V O L . 4 , M A Y , 1 9 4 6 Rutterfield W ill Record For Capitol Capitol Records has signed trumpet-ace Billy Butterfield to an exclusive recording contract. The star trumpet-man is currently en gaged in building a band back in NYC where he will cut his first sides under the new recording deal with C apitol. Contrary to earlier reports which had Butterfield preparing a library for a FREDDIE SLACK looks pretty “ studio” band, that is, a band of hand ELLA MAE MORSE was caught happy sitting at the Steinway and picked irregular musicians meeting for singing the blues at her latest Capi he has a right to the pleased expres occasional wax dates and air shows, the tol disc date, results of which are sion. The boogie-woogie expert has musician wants it made clear that his next crew will be a regular traveling ready for you on record shop coun just released two more Capitol plat outfit. Plans for it are not completely ters right now. With b.w. pianist ter sides co-starring his keyboard set yet (girl and boy singers, for ex Freddie Slack, Miss Morse sw u n g with Ella Mae Morse’s unbeatable ample, haven’t been chosen) but Billy through two new sides ( “ The House vocals. The duo of blues-specialists expects to be on the move with his new of Blue Lights” and “ Hey, Mr. Post who made “Cow Cow Boogie” a crew shortly. man” ) that look powerful enough to household phrase are out to make dim any of her earlier song suc more musical history with two new Duke Ellington cesses. -

Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) Annual Report

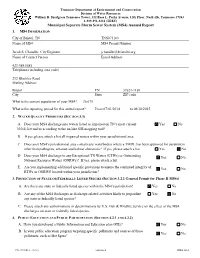

Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation Division of Water Resources William R. Snodgrass Tennessee Tower, 312 Rosa L. Parks Avenue, 11th Floor, Nashville, Tennessee 37243 1-888-891-8332 (TDEC) Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) Annual Report 1. MS4 INFORMATION City of Bristol, TN TNS075183 Name of MS4 MS4 Permit Number Jacob S. Chandler, City Engineer [email protected] Name of Contact Person Email Address 423.989.5585 Telephone (including area code) 212 Blackley Road Mailing Address Bristol TN 37621-1189 City State ZIP code What is the current population of your MS4? 26,675 What is the reporting period for this annual report? From 07/01/2014 to 06/30/2015 2. WATER QUALITY PRIORITIES (SECTION 3.1) A. Does your MS4 discharge into waters listed as impaired on TN’s most current Yes No 303(d) list and/or according to the on-line GIS mapping tool? B. If yes, please attach a list all impaired waters within your jurisdictional area. C. Does your MS4’s jurisdictional area contain any waterbodies where a TMDL has been approved for parameters other than pathogens, siltation and habitat alterations? If yes, please attach a list. Yes No D. Does your MS4 discharge to any Exceptional TN Waters (ETWs) or Outstanding Yes No National Resource Waters (ONRWs)? If yes, please attach a list. E. Are you implementing additional specific provisions to ensure the continued integrity of Yes No ETWs or ONRWS located within your jurisdiction? 3. PROTECTION OF STATE OR FEDERALLY LISTED SPECIES (SECTION 3.2.1 General Permit for Phase II MS4s) A.