What Is the Lived Emotional Experience of First-Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Allman Betts Band

May 2020 May WashingtonBluesletter Blues Society www.wablues.org Remembering Wade Hickam COVID-19 Resources for Musicians Special Feature: Th e Allman Betts Band LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT WASHINGTON BLUES SOCIETY Hi Blues Fans, Proud Recipient of a 2009 You will find lots ofKeeping the Blues Alive Award information in this Bluesletter if you are a musician. Our 2020 OFFICERS editor, Eric Steiner, has kept President, Tony Frederickson [email protected] his eyes open and his ears Vice President, Rick Bowen [email protected] tuned for opportunities that Secretary, Marisue Thomas [email protected] musicians can explore to Treasurer, Ray Kurth [email protected] help them in this challenging Editor, Eric Steiner [email protected] time. He has a real knack for this as he’s worked in public and private sector grant programs. We will continue to print these 2020 DIRECTORS opportunities in both the Bluesletter and post them on our website Music Director, Amy Sassenberg [email protected] (www.wablues.org), and our Facebook page. Please explore these Membership, Chad Creamer [email protected] opportunities and share with your bandmates. Education, Open [email protected] For our members, please continue to practice social distancing, Volunteers, Rhea Rolfe [email protected] wear face masks and stay safe. As we overcome this first wave of Merchandise, Tony Frederickson [email protected] infections and our state reopens, be patient and stay informed as I Advertising, Open [email protected] hope to see all of you out and about once we can go see live music. We will overcome this and be back enjoying all of our favorite THANKS TO THE WASHINGTON BLUES SOCIETY 2020 STREET TEAM playing live music. -

Vintage Uke Music Revised 2020.Xlsx

9/20/2020 Title Folder 12 street rag !no covers a fool such as i (now and then there's) A A Lady Loves ‐ 1952 L A Man Never Marries A Wife ‐ 1951 M A Nickel Ain't Worth A Cent Today ‐ 1951 N A Picnic In The Park ‐ 1951 P A Sleepin' Bee ‐ 1954 S a very precious love !no covers a woman in love !no covers A Woman In Love ‐ 1955 W a you're adorable A abdul the bulbul ameer A Abie's Irish Nose ‐ 1925 A About A Quarter To Nine A absence makes heart grow fonder A accent on youth A ac‐cent‐tchu‐ate the positive A Across The Breakfast Table ‐ 1929 A Adam's Apple A Adelaide ‐ 1955 A Adios A Adorable ‐ 1933 A After a million dreams A after all it's you A After All You're All I'm After ‐ 1930 A After All You're All I'm After ‐ 1933 A After Business Hours ‐ 1929 A after i say i'm sorry A after i've called you sweetheart A After My Laughter Came Tears A After Tea ‐ 1925 A after you A After You Get What You Want A After You Get What You Want You Don't Want It ‐ 1920A After You've Gone A after_my_laughter_came_tears A ah but is it love A Ah But It Is Love ‐1933 A ah sweet mystery of life A Ah Wants To Die From Eatin' Possum Pie ‐ 1925 A Ah! The Moon Is Here ‐ 1933 A ah‐ha A ain't gonna rain new verses A Ain't Got A Dime To My Name ‐ 1942 A ain't it cold !no covers ain't misbehavin' A aint misbehavin vintage !no covers aint no flies on auntie A Ain't No Flies On Aunty A ain't no land like dixie A aint she sweet A Ain't That a Grand and Glorious Feeling ‐ 1927 A Ain't we carryin' on A Ain't We Got Fun A Ain't You Baby A ain't_misbehavin' A Ain't‐cha A alabama -

2013 Syndicate Directory

2013 Syndicate Directory NEW FEATURES CUSTOM SERVICES EDITORIAL COMICS POLITICAL CARTOONS What’s New in 2013 by Norman Feuti Meet Gil. He’s a bit of an underdog. He’s a little on the chubby side. He doesn’t have the newest toys or live in a fancy house. His parents are split up – his single mother supports them with her factory job income and his father isn’t around as often as a father ought to be. Gil is a realistic and funny look at life through the eyes of a young boy growing up under circumstances that are familiar to millions of American families. And cartoonist Norm Feuti expertly crafts Gil’s world in a way that gives us all a good chuckle. D&S From the masterminds behind Mobilewalla, the search, discovery and analytics engine for mobile apps, comes a syndicated weekly column offering readers both ratings and descriptions of highly ranked, similarly themed apps. Each week, news subscribers receive a column titled “Fastest Moving Apps of the Week,” which is the weekly hot list of the apps experiencing the most dramatic increases in popularity. Two additional “Weekly Category” features, pegged to relevant news, events, holidays and calendars, are also available. 3TW Drs. Oz and Roizen give readers quick access to practical advice on how to prevent and combat conditions that affect overall wellness and quality of life. Their robust editorial pack- age, which includes Daily Tips, a Weekly Feature and a Q & A column, covers a wide variety of topics, such as diet, exercise, weight loss, sleep and much more. -

Gennett Sound Recording Collection, Date (Inclusive): 1917-1930 Collection Number: 253-M Creator: Starr Piano Company

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt700026k4 No online items Finding Aid for the Gennett Sound Recording Collection 1917-1930 Processed by Performing Arts Special Collections Staff. Performing Arts Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm ©2009 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Gennett 253-M 1 Sound Recording Collection 1917-1930 Descriptive Summary Title: Gennett Sound Recording Collection, Date (inclusive): 1917-1930 Collection number: 253-M Creator: Starr Piano Company. Gennett Record Division 1917-1932 Extent: 2,142 sound discs Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections Los Angeles, California 90095-1490 Abstract: The collection consists of 78 rpm. sound recordings published by the Gennett Record Company. Physical location: SRLF Language of Material: Collection materials in English Access The collection is open for research. Advance notification is required for use. Publication Rights Property rights in the physical objects belong to the UCLA Music Library. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish if the Music Library does not hold the copyright. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Gennett Sound Recording Collection, 253-M, Performing Arts Special Collections , University of California, Los Angeles. -

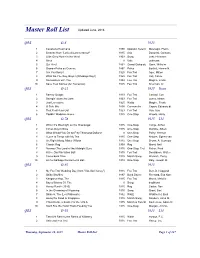

Master Roll List

Master Roll List QRS O-6 1925 1 Cavalleria Rusticana 1890 Operatic Selecti Mascagni, Pietro 2 Sextette from "Lucia di Lammermoor" 1835 Aria Donizetti, Gaetano 3 Little Grey Home in the West 1903 Song Lohr, Hermann 4 Alma 0 Vals unknown 5 Qui Vive! 1862 Grand Galop de Ganz, Wilhelm 6 Grande Polka de Concert 1867 Polka Bartlett, Homer N. 7 Are You Sorry? 1925 Fox Trot Ager, Milton 8 What Do You Say, Boys? (Whadaya Say?) 1925 Fox Trot Voll, Cal de 9 Somewhere with You 1924 Fox Trot Magine, Frank 10 Save Your Sorrow (for Tomorrow) 1925 Fox Trot Sherman, Al QRS O-21 1925 Roen 1 Barney Google 1923 Fox Trot Conrad, Con 2 Swingin' down the Lane 1923 Fox Trot Jones, Isham 3 Just Lonesome 1925 Waltz Magine, Frank 4 O Solo Mio 1898 Canzonetta Capua, Eduardo di 5 That Red Head Gal 1923 Fox Trot Van, Gus 6 Paddlin' Madeline Home 1925 One-Step Woods, Harry QRS O-78 1915 Lbl 1 When It's Moonlight on the Mississippi 1915 One-Step Lange, Arthur 2 Circus Day in Dixie 1915 One-Step Gumble, Albert 3 What Would You Do for Fifty Thousand Dollars? 0 One-Step Paley, Herman 4 I Love to Tango with My Tea 1915 One-Step Alstyne, Egbert van 5 Go Right Along, Mister Wilson 1915 One-Step Brown, A. Seymour 6 Classic Rag 1909 Rag Moret, Neil 7 Norway (The Land of the Midnight Sun) 1915 One-Step, Trot Fisher, Fred 8 At the Old Plantation Ball 1915 Fox Trot Donaldson, Walter 9 Come back Dixie 1915 March Song Wenrich, Percy 10 At the Garbage Gentlemen's Ball 1914 One-Step Daly, Joseph M. -

"A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 Piano Solo | Twelfth 12Th Street Rag 1914 Euday L

Box Title Year Lyricist if known Composer if known Creator3 Notes # "A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 piano solo | Twelfth 12th Street Rag 1914 Euday L. Bowman Street Rag 1 3rd Man Theme, The (The Harry Lime piano solo | The Theme) 1949 Anton Karas Third Man 1 A, E, I, O, U: The Dance Step Language Song 1937 Louis Vecchio 1 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The 1914 Arthur Fields Walter Donovan 1 Abide With Me 1901 John Wiegand 1 Abilene 1963 John D. Loudermilk Lester Brown 1 About a Quarter to Nine 1935 Al Dubin Harry Warren 1 About Face 1948 Sam Lerner Gerald Marks 1 Abraham 1931 Bob MacGimsey 1 Abraham 1942 Irving Berlin 1 Abraham, Martin and John 1968 Dick Holler 1 Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder (For Somebody Else) 1929 Lewis Harry Warren Young 1 Absent 1927 John W. Metcalf 1 Acabaste! (Bolero-Son) 1944 Al Stewart Anselmo Sacasas Castro Valencia Jose Pafumy 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Accidents Will Happen 1950 Johnny Burke James Van Huesen 1 According to the Moonlight 1935 Jack Yellen Joseph Meyer Herb Magidson 1 Ace In the Hole, The 1909 James Dempsey George Mitchell 1 Acquaint Now Thyself With Him 1960 Michael Head 1 Acres of Diamonds 1959 Arthur Smith 1 Across the Alley From the Alamo 1947 Joe Greene 1 Across the Blue Aegean Sea 1935 Anna Moody Gena Branscombe 1 Across the Bridge of Dreams 1927 Gus Kahn Joe Burke 1 Across the Wide Missouri (A-Roll A-Roll A-Ree) 1951 Ervin Drake Jimmy Shirl 1 Adele 1913 Paul Herve Jean Briquet Edward Paulton Adolph Philipp 1 Adeste Fideles (Portuguese Hymn) 1901 Jas. -

New Hire Is Disappointed to Be Working As a Gofer

2E z SATURDAY, JANUARY 25, 2020 z THE DES MOINES REGISTER Dear Abby Comics New hire is disappointed to be working as a gofer Cornered Marmaduke Dear Abby: I recently landed DEAR ABBY is a new job and was excited about written by doing work that would be directly Abigail Van Buren, in line with my education and also known as background. I left a job of more Jeanne Phillips, and than a decade to pursue this feld. was founded by My problem is, I’m being asked to her mother, Pauline carry luggage, make coffee, run Phillips. Write Dear Abby at errands, etc. This was not in my DearAbby.com or P.O. Box 69440, job description, nor was it what I Los Angeles, CA 90069 was hired for. Abby, I have worked many intern positions. I do not believe Dear Scared: I see nothing I am too good for any job, but I wrong with having a discussion have worked my way up and have with your employer. abilities that could contribute However, because you are so greatly to this company. What new to the job, it should be done they have me doing now is not delicately. benefcial for me or them. Tell the person you feel you If you believe I should say could be contributing more to the something, what should it be? company than you are currently I’m afraid they can easily fnd doing, but do not complain about a substitute who may perform the menial tasks. It often falls to these tasks, as they aren’t every the newest member of the team day, but it’s often enough to make to do these things, and the last me uncomfortable. -

One Fine Sunday in the Funny Pages” Exhibit

John Read is the creator and curator of the “One Fine Sunday in the Funny Pages” exhibit. A freelance cartoonist, John also teaches cartooning to children and is the publisher and editor of Stay Tooned! Magazine, considered the trade journal of the craft. The Comic Mode The comic strip provides a colorful and humorous respite from the serious and often tragic news that precedes it. There are many reasons for reading the “funny pages”; from the basic need to be entertained, to the desire to escape for a moment into what seems a playful combination of a joke and a sequence of images that illustrate the nonsense and play that generates it. Yet, what really constitutes the “comic” in a comic strip? Are they simply funny, as in Blondie, Garfield or Hagar the Horrible? Or do we sense underlying tones of irony, satire, political and social commentary as evidenced in Doonesbury, Non Sequitur, and Between Friends? How are we to understand the double entendre, the sting of wit or the twist of the absurd that infuses so many contemporary comic strips? It would seem that as in dreams, there are many levels to the comic mode. On the first take, the superficial or manifest appeal generates a smile or laughter. But as with many dreams and good jokes, there is the second take, a latent need to establish or defy meaning as embedded within the structure of the images themselves. The paradox or playfulness of the comic strip partially lies in discovering the truth in the nonsensical aspects of day-to-day living. -

B4 FRIDAY, JANUARY 12, 2018 LEDGER DISPATCH Baby Blues

B4 FRIDAY, JANUARY 12, 2018 LEDGER DISPATCH FUN & GAMES Popeye Hagar The Horrible Blondie Bizarro Baby Blues Beetle Baily Horoscopes BY FRANCIS DRAKE Dennis the Menace The Family Circus What kind of day will lift your spirits and put opportunity to do so. tomorrow be? To find a bounce in your step!. AQUARIUS out what the stars say, VIRGO (Jan. 20 to Feb. 18) read the forecast given (Aug. 23 to Sept. 22) A subtle feeling for your birth sign. An unexpected of excitement pervades invitation to a social this day for you. It’s as if ARIES event will please you you are waiting to have (March 21 to April 19) today. Likewise, ro- fun, and something An unexpected mance also might hold unexpected is going to flirtation might catch a surprise. However, suddenly blossom. And you off guard today, keep an eye on your indeed, it might! especially because it kids, because this is an PISCES might be with a boss or unpredictable day! (Feb. 19 to March 20) someone in a position LIBRA A friend will of authority. Or perhaps (Sept. 23 to Oct. 22) surprise you today with some other surprise will Surprise compa- pleasant news. This also occur? ny could drop by today, might relate to the arts. TAURUS so you might entertain In a few cases, a friend (April 20 to May 20) at home even if you might become a lover. Surprise oppor- didn’t expect to do so. Today is full of the un- tunities to travel might Stock the fridge! Keep expected. -

Advocate Number 205 | April-June 2019

Advocate Number 205 | April-June 2019 Speaking Out at Mental Health Day on the Hill The Mental Health Legislative Network’s annual Day on the Hill drew over 500 people to the Capitol on March 14 to urge legislators to pass important legislation to expand school-linked mental health services, invest in more supports for children and adults and ensure that insurance parity for mental health care is met. Mental health advocates from around Advocates Looking for Bigger Gains the state participated in the day getting updated on the status of these The Minnesota Legislature is to complete its work by May 20. As this critical issues, visiting legislators and newsletter goes to print the first deadlines have passed but the budget bills holding a vocal rally in the Capitol still need to be put together. It’s too early to measure success. Rotunda. Governor Walz released his budget that included increased funding in several “Today is not the time to be silent. areas of interest to NAMI members. Today is our day to get loud,” shouted state mental health advisory council For children’s mental health, his budget includes over $4 million a year for member Rozenia Fuller as she the school-linked mental health program, funding to offset the loss of federal See “Mental Health Rally” p.3 Medicaid funding for our children’s residential system and increasing the number of Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facility (PRTF) beds from 150 to Elk River Finally Gets 300 beds. IRTS Facility There is continuation funding for the Certified Community Behavioral Health People living in the Elk River area Clinics and an expansion of the Transitions to Community program to support will finally be getting a residential people transitioning out of state-operated mental health services in a timely program for adults recovering from fashion when they no longer require this level of care, along with expanding the a mental illness. -

Vince Giordano Collection Finding Aid (PDF)

University of Missouri-Kansas City Dr. Kenneth J. LaBudde Department of Special Collections NOT TO BE USED FOR PUBLICATION BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Born in Brooklyn, New York, Vince Giordano’s passion for music from the 1920s and 1930s, and the people that made it, began at age 5. He has amassed an amazing collection of over 60,000 band arrangements, 1920s and 1930s films, 78 recordings and jazz-age memorabilia. Giordano sought out and studied with important survivors from the period: Paul Whiteman’s hot arranger Bill Challis and drummer Chauncey Morehouse, as well as bassist Joe Tarto. Giordano’s passion, commitment to authenticity, and knowledge led him to create a sensational band of like-minded players, the Nighthawks. Giordano has single-handedly kept alive an amazing genre of American music that continues to spread the joy and pathos of an era that shaped our nation. A Grammy-winner and multi-instrumentalist, Giordano has played in New York nightclubs, appeared in films such as The Cotton Club, The Aviator, Finding Forrester, Revolutionary Road, and HBO’s Boardwalk Empire; and performed concerts at the Town Hall, Jazz At Lincoln Center and the Newport Jazz Festival. Recording projects include soundtracks for the award- winning Boardwalk Empire with vocalists like Elvis Costello, Patti Smith, St. Vincent, Regina Spektor, Neko Case, Leon Redbone, Liza Minnelli, Catherine Russell, Rufus Wainwright and David Johansen. He and his band have also recorded for Todd Haynes' Carol, Terry Zwigoff’s Ghost World, Tamara Jenkins’ The Savages, Robert DeNiro’s The Good Shepherd, Sam Mendes’ Away We Go, Michael Mann’s Public Enemies, and John Krokidas’ debut feature, Kill Your Darlings; along with HBO’s Grey Gardens and the miniseries Mildred Pierce. -

6 Comics CFP 6-16-11.Indd

Page 6 Colby Free Press Thursday, June 16, 2011 Baby Blues • Rick Kirkman & Jerry Scott Dr. Joyce Family Circus • Bil Keane Brothers Ask • Dr. Brothers Friend sabotages her constantly Dear Dr. Brothers: I don’t know what is Beetle Bailey • Mort Walker wrong, but my friend is trying to sabotage me in our baby group. Maybe I should call her a “fren- emy” instead of a “friend.” She is always mak- ing comparisons between her baby and mine. Her baby can say 36 words, and mine is still stuck on “Mama.” She even mocks my choice of diapers. How do I get her to stop being mean? She never did this before we had kids. – G.D. Dear G.D.: There is something about hav- ing babies and joining baby groups that invites Dave Green competition. Especially if you both are first-time Conceptis Sudoku • By Dave Green mothers, there is a constant search for bench- marks, validation and anything that makes you 6 2 4 feel more secure. Also, it’s never too early to start competing for coveted spots in the leading pre- 7 8 Blondie • Chic Young school. See what I mean? It’s a jungle out there. Your friend/frenemy may be feeling the pres- 1 8 9 sure keenly. In fact, it is likely she is jealous of 3 7 6 you now you have something she doesn’t – a kid she secretly feels is cuter than hers, or more coor- 5 2 dinated, or more attached to Mommy. It could be almost anything. The fact is you will run into peo- 4 8 9 ple like this as long as you have a child in groups with other kids.