Blake's Swans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: from Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence Robert W

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1977 William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: From Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence Robert W. Winkleblack Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Winkleblack, Robert W., "William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: From Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence" (1977). Masters Theses. 3328. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3328 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. �S"Date J /_'117 Author I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because ��--��- Date Author pdm WILLIAM BLAKE'S SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND OF EXPERIENCE: - FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE TO WISE INNOCENCE (TITLE) BY Robert W . -

Introduction

Introduction The notes which follow are intended for study and revision of a selection of Blake's poems. About the poet William Blake was born on 28 November 1757, and died on 12 August 1827. He spent his life largely in London, save for the years 1800 to 1803, when he lived in a cottage at Felpham, near the seaside town of Bognor, in Sussex. In 1767 he began to attend Henry Pars's drawing school in the Strand. At the age of fifteen, Blake was apprenticed to an engraver, making plates from which pictures for books were printed. He later went to the Royal Academy, and at 22, he was employed as an engraver to a bookseller and publisher. When he was nearly 25, Blake married Catherine Bouchier. They had no children but were happily married for almost 45 years. In 1784, a year after he published his first volume of poems, Blake set up his own engraving business. Many of Blake's best poems are found in two collections: Songs of Innocence (1789) to which was added, in 1794, the Songs of Experience (unlike the earlier work, never published on its own). The complete 1794 collection was called Songs of Innocence and Experience Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul. Broadly speaking the collections look at human nature and society in optimistic and pessimistic terms, respectively - and Blake thinks that you need both sides to see the whole truth. Blake had very firm ideas about how his poems should appear. Although spelling was not as standardised in print as it is today, Blake was writing some time after the publication of Dr. -

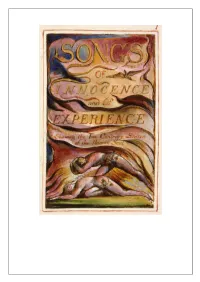

Songs of Innocence Is a Publication of the Pennsylvania State University

This publication of William Blake’s Songs of Innocence is a publication of the Pennsylvania State University. This Portable Document file is furnished free and without any charge of any kind. Any person using this document file, for any purpose, and in any way does so at his or her own risk. Neither the Pennsylvania State University nor Jim Manis, Faculty Editor, nor anyone associated with the Pennsylvania State University assumes any responsibility for the material contained within the document or for the file as an electronic transmission, in any way. William Blake’s Songs of Innocence, the Pennsylvania State University, Jim Manis, Faculty Editor, Hazleton, PA 18201-1291 is a Portable Document File produced as part of an ongoing student publication project to bring classical works of literature, in English, to free and easy access of those wishing to make use of them, and as such is a part of the Pennsylvania State University’s Elec- tronic Classics Series. Cover design: Jim Manis; Cover art: William Blake Copyright © 1998 The Pennsylvania State University Songs of Innocence by William Blake Songs of Innocence was the first of Blake’s illuminated books published in 1789. The poems and artwork were reproduced by copperplate engraving and colored with washes by hand. In 1794 he expanded the book to in- clude Songs of Experience. Frontispiece 3 Songs of Innocence by William Blake Table of Contents 5 …Introduction 17 …A Dream 6 …The Shepherd The images contained 19 …The Little Girl Lost 7 …Infant Joy in this publication are 20 …The Little Girl Found 7 …On Another’s Sorrow copies of William 22 …The Little Boy Lost 8 …The School Boy Blakes originals for 22 …The Little Boy Found 10 …Holy Thursday his first publication. -

Year 8 Spring Term English School Booklet

Module 2 Year 8: Romantic Poetry Songs of Innocence and Experience, William Blake Name: Teacher: 1 The Industrial Revolution Industrial An industrial system or product is one that He rejected all items made using industrial (adjective) uses machinery, usually on a large scale. methods. Natural Natural things exist or occur in nature and She appreciated the natural world when she left (adjective) are not made or caused by people. the chaos of London. William Blake lived from 28 November 1757 until 12 August 1827. At this time, Britain was undergoing huge change, mainly because of the growth of the British Empire and the start of the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution was a time when factories began to be built and the country changed forever. The countryside, natural and rural settings were particularly threatened and many people did not believe they were important anymore because they wanted the money and the jobs in the city. The population of Britain grew rapidly during this period, from around 5 million people in 1700 to nearly 9 million by 1801. Many people left the countryside to seek out new job opportunities in nearby towns and cities. Others arrived from further away: from rural areas in Ireland, Scotland and Wales, for example, and from across large areas of continental Europe. As cities expanded, they grew into centres of pollution and poverty. There were good things about the Industrial Revolution, but not for the average person – the rich factory owners and international traders began to make huge sums of money, and the gap between rich and poor began to widen as a result. -

The Implied Reader in Blake's Songs of Innocence

Colby Quarterly Volume 25 Issue 1 March Article 3 March 1989 Innocence Re-called: The Implied Reader in Blake's Songs of Innocence Deborah Guth Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 25, no.1, March 1989, p.4-11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Guth: Innocence Re-called: The Implied Reader in Blake's Songs of Innoc Innocence Re-called: The Implied Reader in Blake's Songs of Innocence by DEBORAH GUTH T IS one of the axioms of Blake criticism that the two "Contrary States I of the Human Soul," Innocence and Experience, are portrayed separately through the sets of songs bearing their respective names. The Songs ofInnocence, rendered through lilting childlike rhymes, dramatize the enchanted inner world of the child; 1 the following series defines the spiritual landscape of its absence, while critical distance, mutual ex posure, and satire are achieved through the juxtaposition of the two sets of songs within a single composite work (Frye, 237; Bloom, Vis. Co., 34). However, although the Songs ofInnocence are apparently intended for children- "Every child may joy to hear"- closer analysis reveals, within this series alone, complex levels of discourse which are alien to the child's world as well as implied situations and conflicting emotions glimpsed by Innocence but properly belonging to the world of Experience. Most significantly, although the stated purpose of these songs is to portray the state of Innocence, almost all contain forebodings and insights from the world ofExperience which subliminally call on the reader to focus beyond the halcyon world of joy and faith which is their ostensible subject. -

Stylistic Analysis on William Blake's the Little Boy Lost

Jadila: Journal of Development and Innovation E-ISSN: 2723-6900 in Language and Literature Education P-ISSN: 2745-9578 Publisher: Yayasan Karinosseff Muda Indonesia Volume: 1 Number 2, 2020 Page: 175-181 Stylistic Analysis on William Blake’s The Little Boy Lost Olyvia Vita Ardhani English Letter Department, Universitas Sanata Dharma Yogyakarta, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract This research presented the stylistic analysis of a poem by William Blake, The Little Boy Lost. The poem was chosen as it becomes Blake's one of well-known poems in his Song of Innocence. Moreover, this poem uses simple structure and dictions, but it conveys a profound meaning. This research aimed: (1) to discover how the language level in the poem used and (2) to find out the interpretation of the poem. The stylistic analysis aimed at observing the meaning of either literary or non-literary text by the language device used. The researcher conducted a data population method in analyzing the poem. There were four language levels to achieve the goal; they were phonological, graphological, lexical, and syntactic level (Verdonk: 2002). In the phonological level, assonance, consonance, and alliteration were used to emphasize important words. In the graphological level, the comma in the last line of stanza 1 is prominent to distinguish the different speakers. In the lexical level, metaphor was used to voice the little boy's hopes to find enlightenment to get out of his difficulties. Meanwhile, symbolism conveys a deeper meaning than the literal meaning. In the syntactic level, the tenses switching used to emphasize the different speakers and the comma in the graphological level; and the word repetition used to create the little boy's sense of innocence. -

Songs of Innocence and of Experience by William Blake

SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND OF EXPERIENCE BY WILLIAM BLAKE 1789-1794 Songs Of Innocence And Of Experience By William Blake. This edition was created and published by Global Grey 2014. ©GlobalGrey 2014 Get more free eBooks at: www.globalgrey.co.uk No account needed, no registration, no payment 1 SONGS OF INNOCENCE INTRODUCTION Piping down the valleys wild Piping songs of pleasant glee On a cloud I saw a child. And he laughing said to me. Pipe a song about a Lamb: So I piped with merry chear, Piper pipe that song again— So I piped, he wept to hear. Drop thy pipe thy happy pipe Sing thy songs of happy chear, 2 So I sung the same again While he wept with joy to hear. Piper sit thee down and write In a book that all may read— So he vanish’d from my sight, And I pluck’d a hollow reed. And I made a rural pen, And I stain’d the water clear, And I wrote my happy songs, Every child may joy to hear 3 THE SHEPHERD How sweet is the Shepherds sweet lot, From the morn to the evening he strays: He shall follow his sheep all the day And his tongue shall be filled with praise. For he hears the lambs innocent call. And he hears the ewes tender reply. He is watchful while they are in peace, For they know when their Shepherd is nigh. 4 THE ECCHOING GREEN The Sun does arise, And make happy the skies. The merry bells ring, To welcome the Spring. -

William Blake (1757-1827)

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN William Blake (1757-1827) This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • Our sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN 1. The History of the Tate 2. From Absolute Monarch to Civil War, 1540-1650 3. From Commonwealth to the Georgians, 1650-1730 4. The Georgians, 1730-1780 5. Revolutionary Times, 1780-1810 6. Regency to Victorian, 1810-1840 7. William Blake 8. J. M. W. Turner 9. John Constable 10. The Pre-Raphaelites, 1840-1860 West galleries are 1540, 1650, 1730, 1760, 1780, 1810, 1840, 1890, 1900, 1910 East galleries are 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Turner Wing includes Turner, Constable, Blake and Pre-Raphaelite drawings Agenda 1. -

W. Blake: Tiriel and the Book of Thel

W. Blake: Tiriel and 密 The Book of Thel 教 - A Passage to Experience- 文 化 Toshikazu Kashiwagi (1) When Blake completed Songs o f Experience in 1794, he bound it to- gether with Songs of Innocence (1789) and published them in one volume under the full title of Songs of Innocence and of Experience Shelving the Two Contrary States of the Huinan Soul. Songs of Experience is, as it were, an antithesis to Songs of Innocence. The one is in a sharp contrast with the other. It is, however, a serious mistake to overlook the transitional phase from Innocence to Experience. We cannot exactly know when he got an idea of showing the contrary state to Innocence' but he was probably conscious of the necessity to show the contrary state to Innocence before he published Songs of Innocence. For a few Songs of Innocence show us the world of Experience and their author transferred them to Songs of Experience later. My aim in this paper is, however, to examine the transitional phase from Innocence to Experience in special reference to Tiriel (c. 1789) and The Book of Thel (1789). I Early critics and biographers of Blake, including A. Gilchrist and A. C. Swinburne, pay little attention to Tirriel and with some reason, for this allegorical poem is rather a poor and unsuccessful one and the author himself abandoned its publication and it was not printed till (2) 1874, when W. M. Rossetti included it in his edition. But in my present study it bears not a little importance because it shows what kind of problems Blake was concerned with during the transitional period from Innocence to Experience, It is quite significant that Myratana, who was once the Queen of all the western plains, is dying at the outset of Tiriel. -

Songs of Innocence and Experience

Contents General Editor’s Preface x A Note on Editions xi PART 1: ANALYSING WILLIAM BLAKE’S POETRY Introduction 3 The Scope of this Volume 3 Analysing Metre 3 Blake’s Engraved Plates 6 1 Innocence and Experience 9 ‘Introduction’ (Songs of Innocence)9 ‘The Shepherd’ 15 ‘Introduction’ (Songs of Experience)17 ‘Earth’s Answer’ 23 The Designs 30 Conclusions 42 Methods of Analysis 45 Suggested Work 47 2 Nature in Innocence and Experience 50 ‘Night’ 51 ‘The Fly’ 59 ‘The Angel’ 62 ‘The Little Boy Lost’ and ‘The Little Boy Found’ 64 ‘The Little Girl Lost’ and ‘The Little Girl Found’ 68 ‘The Lamb’ 80 ‘The Tyger’ 82 Summary Discussion 91 Nature in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell 93 Conclusions 102 Methods of Analysis 104 Suggested Work 105 vii viii Contents 3 Society and its Ills 107 ‘The Chimney Sweeper’ (Songs of Innocence) 107 ‘The Chimney Sweeper’ (Songs of Experience) 113 ‘Holy Thursday’ (Songs of Innocence) 117 ‘Holy Thursday’ (Songs of Experience) 118 ‘The Garden of Love’ 121 ‘London’ 125 Toward the Prophetic Books 130 The Prophetic Books 134 Europe: A Prophecy 134 The First Book of Urizen 149 Concluding Discussion 154 Methods of Analysis 157 Suggested Work 160 4 Sexuality, the Selfhood and Self-Annihilation 161 ‘The Blossom’ and ‘The Sick Rose’ 161 ‘A Poison Tree’ 166 ‘My Pretty Rose Tree’ 170 ‘The Clod & the Pebble’ 173 Selfhood and Self-Annilhilation in the Prophetic Books 177 The Book of Thel 178 The First Book of Urizen 182 Milton, A Poem 187 Suggested Work 192 PART 2: THE CONTEXT AND THE CRITICS 5 Blake’s Life and Works 197 Blake’s Life 197 Blake’s Works 206 Blake in English Literature 209 Blake as a ‘Romantic’ Poet 210 6 A Sample of Critical Views 220 General Remarks 220 Northrop Frye and David V. -

Blake's Poetry and Designs

A NORTON CRITICAL EDITION BLAKE'S POETRY AND DESIGNS ILLUMINATED WORKS OTHER WRITINGS CRITICISM Second. Edition Selected and Edited by MARY LYNN JOHNSON UNIVERSITY OF IOWA JOHN E. GRANT UNIVERSITY OF IOWA W • W • NORTON & COMPANY • New York • London Contents Preface to the Second Edition xi Introduction xiii Abbreviations xvii Note on Illustrations xix Color xix Black and White XX Key Terms XXV Illuminated Works 1 ALL RELIGIONS ARE ONE/THERE IS NO NATURAL RELIGION (1788) 3 All Religions Are One 5 There Is No Natural Religion 6 SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND OF EXPERIENCE (1789—94) 8 Songs of Innocence (1789) 11 Introduction 11 The Shepherd 13 The Ecchoing Green 13 The Lamb 15 The Little Black Boy 16 The Blossom 17 The Chimney Sweeper 18 The Little Boy Lost 18 The Little Boy Found 19 Laughing Song 19 A Cradle Song 20 The Divine Image 21 Holy Thursday 22 Night 23 Spring 24 Nurse's Song 25 Infant Joy 25 A Dream 26 On Anothers Sorrow 26 Songs of Experience (1793) 28 Introduction 28 Earth's Answer 30 The Clod & the Pebble 31 Holy Thursday 31 The Little Girl Lost 32 The Little Girl Found 33 vi CONTENTS The Chimney Sweeper 35 Nurses Song 36 The Sick Rose 36 The Fly 37 The Angel 38 The Tyger 38 My Pretty Rose Tree 39 Ah! Sun-Flower 39 The Lilly 40 The Garden of Love 40 The Little Vagabond 40 London 41 The Human Abstract 42 Infant Sorrow 43 A Poison Tree 43 A Little Boy Lost 44 A Little Girl Lost 44 To Tirzah 45 The School Boy 46 The Voice of the Ancient Bard 47 THE BOOK OF THEL (1789) 48 VISIONS OF THE DAUGHTERS OF ALBION (1793) 55 THE MARRIAGE OF HEAVEN AND HELL (1790) 66 AMERICA A PROPHECY (1793) 83 EUROPE A PROPHECY(1794) 96 THE SONG OF Los (1795) 107 Africa 108 Asia 110 THE BOOK OF URIZEN (1794) 112 THE BOOK OF AHANIA (1794) 130 THE BOOK OF LOS (1795) 138 MILTON: A POEM (1804; c. -

Macmillan Master Guides

MACMILLAN MASTER GUIDES GENERAL EDITOR: JAMES GIBSON Published JANE AUSTEN Emma Norman Page Sense and Sensibility Judy Simons Pride and Prejudice Raymond Wilson Mansfield Park Richard Wirdnam SAMUEL BECKETT Waiting for Godot Jennifer Birkett WILLIAM BLAKE Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience Alan Tomlinson ROBERT BOLT A Man for all Seasons Leonard Smith EMILY BRONTE Wuthering Heights Hilda D. Spe2r GEOFFREY CHAUCER The Miller's Tale Michael Alexander The Pardoner's Tale Geoffrey Lester The Prologue to the Canterbury Tales Nigel Thomas and Richard Swan CHARLES DICKENS Bleak House Dennis Butts Great Expectations Dennis Butts Hard Times Norman Page GEORGE ELIOT Middlemarch Graham Handley Silas Marner Graham Handley The Mill on the Floss Helen Wheeler HENRY FIELDING Joseph Andrews Trevor Johnson E. M. FORSTER Howards End Ian Milligan A Passage to India Hilda D. Spear WILLIAM GOLDING The Spire Rosemary Sumner Lord of the Flies Raymond Wilson OLIVER GOLDSMITH She Stoops to Conquer Paul Ranger THOMAS HARDY The Mayor of Casterbridge Ray Evans Tess of the d'Urbervilles James Gibson Far from the Madding Crowd Colin Temblett-Wood JOHN KEATS Selected Poems John Garrett PHILIP LARKIN The Whitsun Weddings and The Less Deceived Andrew Swarbrick D. H. LAWRENCE Sons and Lovers R. P. Draper HARPER LEE To Kill a Mockingbird Jean Armstrong CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE Doctor Faustus David A. Male THE METAPHYSICAL POETS Joan van Emden MACMILLAN MASTER GUIDES THOMAS MIDDLETON and The Changeling Tony Bromham WILLIAM ROWLEY ARTHUR MILLER The Crucible Leonard Smith