The Nano Controversy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Containment Zones of Hooghly

Hooghly District Containtment Areas [Category A] w.e.f 27th August , 2020 Annexure-1 Block/ Sl No. Sub Div GP/ Ward Police Station Containtment Area Zone A Municipality ENTIRE HOUSE OF KRISHNA CHOWDHURY INFRONT- SHOP-UMA TELECOM, BACK SIDE- ROAD, RIGHT SIDE:-RATION SHOP, LEFT SIDE:- SHOP-DURGA PHARMACY & Surrounding area of Zone A of ward no. 20 of Bansberia Municipality ,AC 193,PS 130 1 Sadar Bansberia Ward No. 20 MOGRA ENTIRE HOUSE OF PROTAB KAR ,IN FRONT- HOUSE OF AMMULYA CHAKRABORTY BACKSIDE- HOUSE OF BISHAL THAKUR RIGHT SIDE:HOUSE OF DR JAGANATH MAJUMDAR LEFT SIDE:- HOUSE OF DULAL BOSE & Surrounding area of Zone A of ward no. 20 of Bansberia Municipality ,AC 193,PS 130 Entire house of Bipradas Mukherjee,Chinsurah Station Road, Chinsurah, Hooghly, Surrounding area of house of Bipradas Mukherjee, East Side- H/O Biswadulal Chatterjee, West Side- Road , North Side- H/O Pranab Mukherjee, South Side- Pond Sansad -VI, PS-142, Kodalia-I GP,Block -Chinsurah-Mogra & Surrounding area of Zone A of Sansad -VI, PS-142, Kodalia-I GP,Block -Chinsurah-Mogra H/o ASHA BAG, Surrounding area of house of ASHA BAG, East Side- Balai Das West Side- Basu Mondal , North Side- Nidhir halder South Side- Nemai Mondal Sansad-VI, PS- 142 of Kodalia-I GP, Chinsurah-Mogra Block & Surrounding area of Zone A of Sansad -VI, PS-142, Kodalia-I GP,Block -Chinsurah-Mogra 2 Sadar Chinsurah-Mogra Kodalia-II Chinsurah A ZoneAnanda Appartment, 2nd Floor,whole Ananda Appartment Sansad-VI, PS- 142 of Kodalia-I GP, Chinsurah-Mogra Block & Surrounding area of Zone A of Sansad -VI, PS-142, Kodalia-I GP,Block -Chinsurah-Mogra H/O Alo Halder ,Surrounding area of house of ALO HALDER ., East Side- H/O Rina Hegde West Side-Vacant Land , North Side- H/O Sabita Biswas South Side- H/OJamuna Mohanti Sansad-VI, PS- 142of Kodalia-I GP, Chinsurah-Mogra Block & Surrounding area of Zone A of Sansad -VI, PS-142, Kodalia-I GP,Block -Chinsurah-Mogra Hooghly District Containtment Areas [Category A] w.e.f 27th August , 2020 Annexure-1 Block/ Sl No. -

Duare Sarkar & Paray Samadhan,2021

DUARE SARKAR & PARAY SAMADHAN,2021 CAMP SCHEDULE OF DISTRICT HOOGHLY Camp Sl No District BLock/Local Body GP/Ward Venue Date 1 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY Tarakeswar (M) Ward - 008,Ward - 009,Ward - SAHAPUR PRY. SCHOOL 2 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY Champdany (M) Ward - 005 UPHC II HEALTH CENTER 3 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY Chandannagar MC (M) Ward - 003 Goswami Ghat Community Hall Ward - 018,Ward - 019,Ward - NAGENDRANATH KUNDU 4 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY Konnagar (M) 020 VIDYAMANDIR CHAMPDANY BISS FREE PRIMARY 5 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY Champdany (M) Ward - 002 SCHOOL 6 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY SINGUR SINGUR-II Gopalnagar K.R. Dey High School 7 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY GOGHAT-1 BALI BALI HIGH SCHOOL 8 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY BALAGARH MOHIPALPUR Mohipalpur Primary School 9 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY MOGRA-CHUNCHURA MOGRA-I Mogra Uttam Chandra High School 10 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY BALAGARH EKTARPUR Ekterpur U HS 11 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY TARAKESWAR SANTOSHPUR Gouribati Radharani Das High School 12 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY HARIPAL JEJUR Jejur High School Bankagacha Nanilal Ghosh Nimno 13 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY CHANDITALA-2 NAITI Buniadi Vidyalaya 14 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY PURSHURA SHYAMPUR Shyampur High School 15 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY POLBA-DADPUR SATITHAN Nabagram Pry School 16 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY JANGIPARA ANTPUR Antpur High School 17 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY PANDUA SIMLAGARHVITASIN Talbona Radharani Girls High School 18 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY PANDUA SIMLAGARHVITASIN Ranagarh High School SRI RAMKRISHNA SARADA VIDYA 19 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY GOGHAT-2 KAMARPUKUR MAHAPITHA Ward - 017,Ward - 018,Ward - PALBAGAN DURGA MANDIR ARABINDA 20 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY Bhadreswar (M) 019,Ward - 020 SARANI PARUL RAMKRISHNA SARADA HIGH 21 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY Arambagh (M) Ward - 001,Ward - 002 SCHOOL 22 16-08-2021 HOOGHLY CHANDITALA-1 AINYA Akuni B.G. -

W.B.C.S.(Exe.) Officers of West Bengal Cadre

W.B.C.S.(EXE.) OFFICERS OF WEST BENGAL CADRE Sl Name/Idcode Batch Present Posting Posting Address Mobile/Email No. 1 ARUN KUMAR 1985 COMPULSORY WAITING NABANNA ,SARAT CHATTERJEE 9432877230 SINGH PERSONNEL AND ROAD ,SHIBPUR, (CS1985028 ) ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS & HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 14-01-1962 E-GOVERNANCE DEPTT. 2 SUVENDU GHOSH 1990 ADDITIONAL DIRECTOR B 18/204, A-B CONNECTOR, +918902267252 (CS1990027 ) B.R.A.I.P.R.D. (TRAINING) KALYANI ,NADIA, WEST suvendughoshsiprd Dob- 21-06-1960 BENGAL 741251 ,PHONE:033 2582 @gmail.com 8161 3 NAMITA ROY 1990 JT. SECY & EX. OFFICIO NABANNA ,14TH FLOOR, 325, +919433746563 MALLICK DIRECTOR SARAT CHATTERJEE (CS1990036 ) INFORMATION & CULTURAL ROAD,HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 28-09-1961 AFFAIRS DEPTT. ,PHONE:2214- 5555,2214-3101 4 MD. ABDUL GANI 1991 SPECIAL SECRETARY MAYUKH BHAVAN, 4TH FLOOR, +919836041082 (CS1991051 ) SUNDARBAN AFFAIRS DEPTT. BIDHANNAGAR, mdabdulgani61@gm Dob- 08-02-1961 KOLKATA-700091 ,PHONE: ail.com 033-2337-3544 5 PARTHA SARATHI 1991 ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER COURT BUILDING, MATHER 9434212636 BANERJEE BURDWAN DIVISION DHAR, GHATAKPARA, (CS1991054 ) CHINSURAH TALUK, HOOGHLY, Dob- 12-01-1964 ,WEST BENGAL 712101 ,PHONE: 033 2680 2170 6 ABHIJIT 1991 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR SHILPA BHAWAN,28,3, PODDAR 9874047447 MUKHOPADHYAY WBSIDC COURT, TIRETTI, KOLKATA, ontaranga.abhijit@g (CS1991058 ) WEST BENGAL 700012 mail.com Dob- 24-12-1963 7 SUJAY SARKAR 1991 DIRECTOR (HR) BIDYUT UNNAYAN BHAVAN 9434961715 (CS1991059 ) WBSEDCL ,3/C BLOCK -LA SECTOR III sujay_piyal@rediff Dob- 22-12-1968 ,SALT LAKE CITY KOL-98, PH- mail.com 23591917 8 LALITA 1991 SECRETARY KHADYA BHAWAN COMPLEX 9433273656 AGARWALA WEST BENGAL INFORMATION ,11A, MIRZA GHALIB ST. agarwalalalita@gma (CS1991060 ) COMMISSION JANBAZAR, TALTALA, il.com Dob- 10-10-1967 KOLKATA-700135 9 MD. -

Land Acquisition and Compensation in Singur: What Really Happened?∗

Land Acquisition and Compensation in Singur: What Really Happened?∗ Maitreesh Ghatak,† Sandip Mitra,‡ Dilip Mookherjee§and Anusha Nath¶ March 29, 2012 Abstract This paper reports results of a household survey in Singur, West Bengal concerning compensation offered by the state government to owners of land acquired to make way for a car factory. While on average compensations offered were close to the reported market valuations of land, owners of high grade multi-cropped (Sona) lands were under- compensated, which balanced over-compensation of low grade mono-cropped (Sali) lands. This occurred owing to misclassification of most Sona land as Sali land in the official land records. Under-compensation relative to market values significantly raised the chance of compensation offers being rejected by owners. There is considerable ev- idence of the role of financial considerations in rejection decisions. Land acquisition significantly reduced incomes of owner cultivator and tenant households, despite their efforts to increase incomes from other sources. Agricultural workers were more adversely affected relative to non-agricultural workers, while the average impact on workers as a whole was insignificant. Adverse wealth effects associated with under-compensation significantly lowered household accumulation of consumer durables, while effects on other assets were not perceptible. Most households expressed preferences for non-cash forms of compensation, with diverse preferences across different forms of non-cash com- pensation depending on occupation and time preferences. ∗We are grateful to Mr. Atmaram Saraogi of International Centre, Kolkata for sharing with us relevant documents, and the International Growth Centre for financial support under Research Award RA-2009-11- 025 (RST-U145). -

Kolkata 700 017 Ph

WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTION COMMISSION 18, Sarojini Naidu Sarani (Rawdon Street) – Kolkata 700 017 Ph. No. 2280-5805; FAX- 2280-7373 No. 1820-SEC/1D-134/2012 Kolkata, the 3rd December, 2012 O R D E R In exercise of the power conferred by Sections 16 and 17 of the West Bengal Panchayat Elections Act, 2003 (West Bengal Act XXI of 2003), read with rules 26 and 27 of the West Bengal Panchayat Elections Rules, 2006, West Bengal State Election Commission, hereby publish the draft Order for delimitation of North 24 Parganas Zilla Parishad constituencies and reservation of seats thereto. The Block(s) have been specified in column (1) of the Schedule below (hereinafter referred to as the said Schedule), the number of members to be elected to the Zilla Parishad specified in the corresponding entries in column (2), to divide the area of the Block into constituencies specified in the corresponding entries in column (3),to determine the constituency or constituencies reserved for the Scheduled Tribes (ST), Scheduled Castes (SC) or the Backward Classes (BC) specified in the corresponding entries in column (4) and the constituency or constituencies reserved for women specified in the corresponding entries in column (5) of the said schedule. The draft will be taken up for consideration by the State Election Commissioner after fifteen days from this day and any objection or suggestion with respect thereto, which may be received by the Commission within the said period, shall be duly considered. THE SCHEDULE North 24 Parganas Zilla Parishad North 24 Parganas District Name of Number of Number, Name and area Constituenci- Constituen- Block members to of the Constituency es reserved cies be elected for ST/SC/ BC reserved for to the Zilla persons women Parishad (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) Bagdah 3 Bagdah/ ZP-1 SC Women Sindrani, Malipota and Kaniara-II grams. -

NTSE 2021 ALL MERIT LIST.Pdf

Govt. of West Bengal PAGE NO.1/29 Directorate of School Education Bikash Bhawan, 7th floor Salt Lake, Kolkata-91 NATIONAL TALENT SEARCH EXAMINATION (NTSE-1 ) FOR STATE LEVEL, 2021 MERIT LIST OF SELECTED STUDENTS ( 569 + Tie-up cases ) DATE OF BIRTH SCHOOL AREA OF CASTE DISABILITY MAT SAT TOTAL SLNO ROLL NO NAME OF THE CANDIDATE DISTRICT POSTAL ADDRESS FOR CORESPONDENCE NAME AND ADDRESS OF SCHOOL GENDER RANK CODE RESIDENCE CATEGORY STATUS MARKS MARKS MARKS DATE MONTH YEAR SIMLAPAL-BANKUL NEAR DISHARI CLINIC , SIMLAPAL M.M. HIGH SCHOOL , BANKURA 1 23213112061 ARNAB PATI BANKURA 07 09 2005 19132004504 1 1 1 6 98 93 191 1 BANKURA , WEST BENGAL 722151 , WEST BENGAL 722151 DURGAPUR-C-II/20-1 CMERI COLONY , PASCHIM CARMEL SCHOOL DURGAPUR , PASCHIM 2 23213508117 ANKITA MANDAL PASCHIM BURDWAN 18 09 2004 2 2 3 6 99 90 189 2 BARDDHAMAN , WEST BENGAL 713209 BURDWAN , WEST BENGAL NEW BARRACKPUR KOLKATA-348/9 MAIN ROAD RAMKRISHNA MISSION BOYS HOME HIGH WEST SANKARPUKUR NORTH MAYAR KHELA 3 23213205401 ARITRA AMBUDH DUTTA BARRACKPORE 11 04 2005 SCHOOL HS , BARRACKPORE , WEST 19113800406 1 2 1 6 95 91 186 3 APARTMENT FLAT NO 4 , NORTH TWENTY FOUR BENGAL 700118 PARGANAS , WEST BENGAL 700131 BANKURA-KATJURIDANGA DINABANDHU VIVEKANANDA SIKSHA NIKETAN HIGH 4 23213104163 RAKTIM KUNDU BANKURA 04 04 2005 PALLY KENDUADIHI BANKURA , BANKURA , SCHOOL , BANKURA , WEST BENGAL 19130107203 1 1 1 6 97 89 186 4 WEST BENGAL 722102 277146 KOLKATA-39 SN PAUL ROAD GANAPATI ADAMAS INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL , 5 23213203212 ARNAB DAS BARRACKPORE 17 10 2004 ENCLAVE BLOCK A FLAT 2A -

West Bengal.Pdf

F.No. 15-1/2014-RMSA-IV Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of School Education and Literacv ,f**d<rF Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi Dated 30th Mav.20l4 To, The Secretary (Education) Government of West Bengal, Secondary Education (RMSA), Kolkata-700091. Subject: 39th Project Approval Board (pAB) meeting (l9th composite Meeting) for Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA) held on 24th March,-2lr4 to consider plan Annual work & Budget 20r4-r5 for the State of west Bengal. Sir, Please find enclosed herewith Minutes of the 39th Project Approval Board (pAB) Meeting held on 24th March, 2014 approved by Secretary (SE&L), Chairperson, pAB for RMSA and its constituent schemes i.e Vocational Education, ICT@School, IEDSS, Girls Hostel as regards Annual Work Plan & Budget 2014-15 for the State of West Bengal for information and necessary action at your end. (Ankita Mishra euildela) Deputy Secretary to the Government of India Tel:011-23383872 Encl: As above F.No.15-1/2014-RMSA-IV Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of School Education and Literacy ***** Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi 20th May, 2014 MINUTES OF THE 39TH PROJECT APPROVAL BOARD MEETING (19TH COMPOSITE MEETING) HELD ON 24TH MARCH, 2014, FOR APPROVAL OF THE ANNUAL WORK PLAN & BUDGET FOR RASHTRIYA MADHYAMIK SHIKSHA ABHIYAN (RMSA) AND ITS CONSTITUENT SCHEMES INCLUDING ICT, GIRL’S HOSTEL,VOCATIONAL EDUCATION AND IEDSS FOR THE FOR THE STATE OF WEST BENGAL FOR 2014-15. 1. The Meeting of the Project Approval Board for considering the Annual Work Plan & Budget 2014-15 for the State of West Bengal under Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA), ICT, Girls’ Hostels, Vocational Education and IEDSS was held on 24th March, 2014, under the Chairpersonship of Shri R. -

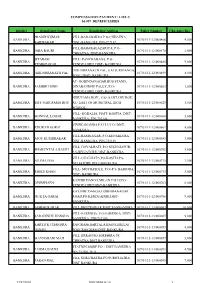

Compensation Payment : List-5 66,059 Beneficiaries

COMPENSATION PAYMENT : LIST-5 66,059 BENEFICIARIES District Beneficiary Name Beneficiary Address Policy Number Chq.Amt.(Rs.) PRADIP KUMAR VILL-BARABAKRA P.O-CHHATNA, BANKURA 107/01/11-12/000466 4,500 KARMAKAR DIST-BANKURA, PIN-722132 VILL-BARAKALAZARIYA, P.O- BANKURA JABA BAURI 107/01/11-12/000476 2,000 CHHATNA, DIST-BANKURA, SITARAM VILL- PANCHABAGA, P.O- BANKURA 107/01/11-12/000486 9,000 KUMBHAKAR KENDUADIHI, DIST- BANKURA, HIRENDRANATH PAL, KATJURIDANGA, BANKURA HIRENDRANATH PAL 107/01/11-12/000499 8,000 POST+DIST- BANKURA. AT- GOBINDANAGAR BUS STAND, BANKURA SAMBHU SING DINABANDHU PALLY, P.O- 107/01/11-12/000563 1,500 KENDUADIHI, DIST- BANKURA, NIRUPAMA ROY , C/O- SANTANU ROU, BANKURA SMT- NIRUPAMA ROY AT- EAST OF MUNICIPAL HIGH 107/01/11-12/000629 5,000 SCHOOL, VILL- KODALIA, POST- KOSTIA, DIST- BANKURA MONGAL LOHAR 107/01/11-12/000660 5,000 BANKURA, PIN-722144. VIVEKANANDA PALLI, P.O+DIST- BANKURA KHOKAN GORAI 107/01/11-12/000661 8,000 BANKURA VILL-RAMNAGAR, P.O-KENJAKURA, BANKURA AJOY KUMBHAKAR 107/01/11-12/000683 3,000 DIST-BANKURA, PIN-722139. VILL-GOYALHATI, P.O-NIKUNJAPUR, BANKURA SHAKUNTALA BAURI 107/01/11-12/000702 3,000 P.S-BELIATORE, DIST-BANKURA, VILL-GUALHATA,PO-KOSTIA,PS- BANKURA NILIMA DAS 107/01/11-12/000715 1,500 BELIATORE,DIST-BANKURA VILL- MOYRASOLE, P.O+P.S- BARJORA, BANKURA RINKU KHAN 107/01/11-12/000743 3,000 DIST- BANKURA, KAJURE DANGA,MILAN PALLI,PO- BANKURA DINESH SEN 107/01/11-12/000763 6,000 KENDUADIHI,DIST-BANKURA KATJURE DANGA,GOBINDANAGAR BANKURA MUKTA GARAI ROAD,PO-KENDUADIHI,DIST- 107/01/11-12/000766 9,000 BANKURA BANKURA ASHISH KARAK VILL BHUTESWAR POST SANBANDHA 107/01/12-13/000003 10,000 VILL-SARENGA P.O-SARENGA DIST- BANKURA SARADINDU HANSDA 107/01/12-13/000007 9,000 BANKURA PIN-722150 KARTICK CHANDRA RAJGRAM(BARTALA BASULIMELA) BANKURA 107/01/12-13/000053 8,000 HENSH POST RAJGRAM DIST BANKURA VILL JIRRAH PO JOREHIRA PS BANKURA MAYNARANI MAJI 107/01/12-13/000057 5,000 CHHATNA DIST BANKURA STATION MORE PO + DIST BANKURA BANKURA PADMA BAURI 107/01/12-13/000091 4,500 PIN 722101 W.B. -

PHC Raipur II Dumurtor 10 BHP 44 Hatgram P.H.C

Sl. Upgraded Under Name of the Institution Block Post Office Beds No. Program District : Bankura Sub- Division : Sadar 1 Helna Susunia P.H.C. Bankura-I Helna Susunia 10 BHP 2 Kenjakura P.H.C. Bankura-I Kanjakura 10 BHP 3 Narrah P.H.C. Bankura-II Narrah 4 4 Mankanali P.H.C. Bankura-II Mnkanali 10 5 Jorhira P.H.C. Chhatna Jorhira 10 6 Salchura (Kamalpur) P.H.C. Chhatna Kamalpur 2 7 Jhantipahari P.H.C. Chhatna Jhantipahari 6 8 Bhagabanpur P.H.C. Chhatna Bhagabanpur 6 9 Gogra P.H.C. Saltora Gogra 10 BHP 10 Ituri P.H.C. Saltora Tiluri 10 BHP 11 Kashtora P.H.C. Saltora Kashtora 6 12 Gangajalghati P.H.C. Gangajalghati Gangajalghati 4 Ramharipur P.H.C.(Swami 13 Gangajalghati Ramharipur 4 Vivekananda) 14 Srichandrapur P.H.C. Gangajalghati Srichandrapur 10 15 Ramchandrapur P.H.C. Mejhia Ramchandrapur 4 16 Pairasole P.H.C. Mejhia Pairasole 10 17 Beliatore P.H.C. Barjora Beliatore 10 18 Chhandar P.H.C. Barjora Chhandar 4 19 Godardihi (Jagannathpur) P.H.C. Barjora Godardihi 4 20 Pakhanna P.H.C. Barjora Pakhanna 10 Sl. Upgraded Under Name of the Institution Block Post Office Beds No. Program 21 Ratanpur P.H.C. Onda Ratanpur 10 BHP 22 Nakaijuri P.H.C. Onda Ghorasol 10 BHP 23 Ramsagar P.H.C. Onda Ramsagar 10 BHP 24 Santore P.H.C. Onda Garh Kotalpur 10 BHP 25 Nikunjapur P.H.C. Onda Nikunjapur 10 BHP Sub- Division : Khatra 26 Bonabaid P.H.C. Khatra-I Kankradara 10 27 Mosiara (Dharampur) P.H.C. -

Left on Trial

SINGUR PUBLIC HEARING LEFT ON TRIAL [Singur, the area with thickly populated farmer communities, is not more than just 40 km away from Kolkata, the capital of the CPM-led Left Front ruled-state of West Bengal. As in any other rural part of India, no doubt the habitats which are generations old have a diversity of occupations pursued by the people : agriculturalists-landholders, farmers and farm labourers, artisans as well as small traders and other self-employed as well as the migrant and resident labourers. The conflict over the land take-over in Singur region by the State Government of West Bengal began when the chief minister of the just-elected 7th Left Front government, Shri Buddhadev Bhattacharya, declared in May,2006, that at least 1000 acres of land in the villages—Gopalnagar, Beraberi, Bajemelia, Khaser Bheri and Singher Bheri—was to be acquired under the British-made Land Acquision Act (1894) within months for a cheap automobile factory by the Tatas. The Singur-based mass organisation of the affected, Krishi Bhumi Bachao Committee and other democratic organisations like the long-serving Association for the Protection of Democratic Rights(APDR) organised a Public Hearing in Singur area on October 27, 2006. Mahasweta Devi, Medha Patekar, Justice (Retd.) Malay Sengupta and Dipankar Chakrabarti comprised the panel. Following excerpts are from the Report (final) of the Public Hearing and further Investigation on the struggle of the People of Singur.] The facts which came out include the following: 1. There are more than 10,000 families who live on the 1000 acres of land and other natural resources to be acquisitioned and destroyed for the upcoming Tata Motors (small, cheap car production) Project. -

Gopalnagar(East) OFFICE of the EXECUTIVE ENGINEER Singur

IRRIGATION AND WATERWAYS DIRECTORATE Gopalnagar(East) OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE ENGINEER Singur : Hooghly LOWER DAMODAR IRRIGATION DIVISION Tel.-033-26300170 ******************************************************************************************* Notice Inviting Tender No:- 13 of 2017-18 of Executive Engineer, Lower Damodar Irrigation Division 1. Separate Sealed Tenders in printed form invited by the Executive Engineer, Lower Damodar Irrigation Division on behalf of the Governor of West Bengal, for the Works as per list attached herewith from eligible bonafied outsides having credential of execution similar nature of work of Value 30% of the amount put to Tender within the last 5 years. 2. a. Separate Tender should be submitted for each work as per attached List in Sealed Cover super scribing the name of the work on the envelop and addressed to the proper authority. b. Submission of Tender by post is not allowed 3. The Tender documents and other relevant particulars (if any) may be seen by the intending Tenderer or by their duly authorized representative during office hours between 11.00 A.M to 4 P.M on every working day, Upto 27.02.2018. in the Office of the Executive Engineer, Lower Damodar Irrigation Division. 4. a. Intending Tenderers should apply for Tender papers in their respective Letter Heads enclosing self attested copies of the following documents, original of which and documents like Registered Partnership (for Partnership farms) etc. are to be produced on demand , as well as during interview (if any). i) PTPC, Trade License, Val id P AN iss ued b y th e IT Dept t., Go vt. of Ind ia, Va lid 15 -digit Goods a nd Se rvices Taxp ayer I den ti fica ti on Number (G STI N) under GST Ac t, 201 7 etc . -

North 24 Parganas

Present Place of District Sl No Name Post Posting DPMU, DH&FWS, CMOH OFFICE N 24 Pgs 1 PRATAP MAJUMDER DPC NORTH 24 PARGANAS, Barasat DPMU, DH&FWS, CMOH OFFICE N 24 Pgs 2 JAYANTA KUMAR PAL DAM NORTH 24 PARGANAS, Barasat DPMU, DH&FWS, CMOH OFFICE N 24 Pgs 3 Goutam Maity DSM NORTH 24 PARGANAS, Barasat DPMU, DH&FWS, CMOH OFFICE N 24 Pgs 4 SAMIRAN KARMAKAR Account Assistant NORTH 24 PARGANAS, Barasat DPMU, DH&FWS, CMOH OFFICE N 24 Pgs 5 APAN SEN Computer Assistant NORTH 24 PARGANAS, Barasat DPMU, DH&FWS, NORTH 24 N 24 Pgs 6 KRISHNA BISWAS AE PARGANAS, Barasat DPMU, DH&FWS, NORTH 24 N 24 Pgs 7 PRONAB HALDER SAE PARGANAS, Barasat N 24 Pgs 8 Dr.Sudip Sarkar GDMO Amdanga BPHC N 24 Pgs 9 Dr.Mudhusudhan Mirdha GDMO Jogeshgunj PHC N 24 Pgs 10 Dr.Mahuya Saha GDMO Goshpur BPHC N 24 Pgs 11 Dr Mannaf Ali GDMO Nazat PHC Dr.Kushik Das GDMO Madhayam Gram N 24 Pgs 12 RH Dr. Surendra Nath Mondal GDMO Bagbon Saiberia N 24 Pgs 13 PHC N 24 Pgs 14 Dr.Debansu Sarkar GDMO Nataberia PHC N 24 Pgs 15 Dr.Soumyajit Chakrabarti GDMO PallaPHC N 24 Pgs 16 Dr.Pusun kr Ghosh GDMO Bandipur BPHC N 24 Pgs 17 Dr.Asim Sarkar GDMO Bandipur BPHC N 24 Pgs 18 Dr.Santunu Sarkar GDMO Barunhat PHC N 24 Pgs 19 Dr.Partha Sarathi Biswas GDMO Routara PHC N 24 Pgs 20 Dr.Shamol Kanta Kundu GDMO Chad para BPHC N 24 Pgs 21 Dr.Pradip Kr Dutta GDMO Chad para BPHC N 24 Pgs 22 Dr.Manoj Mondal GDMO Dharampur PHC N 24 Pgs 23 Dr.Dilip Biswas GDMO Minakha RH N 24 Pgs 24 Dr.Indranil Khatua GDMO Rajarhat BPHC N 24 Pgs 25 Dr.Dilip Patra GDMO Harowa BPHC N 24 Pgs 26 Dr.