3 Principle of Virtual Work And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamilton's Principle in Continuum Mechanics

Hamilton’s Principle in Continuum Mechanics A. Bedford University of Texas at Austin This document contains the complete text of the monograph published in 1985 by Pitman Publishing, Ltd. Copyright by A. Bedford. 1 Contents Preface 4 1 Mechanics of Systems of Particles 8 1.1 The First Problem of the Calculus of Variations . 8 1.2 Conservative Systems . 12 1.2.1 Hamilton’s principle . 12 1.2.2 Constraints.......................... 15 1.3 Nonconservative Systems . 17 2 Foundations of Continuum Mechanics 20 2.1 Mathematical Preliminaries . 20 2.1.1 Inner Product Spaces . 20 2.1.2 Linear Transformations . 22 2.1.3 Functions, Continuity, and Differentiability . 24 2.1.4 Fields and the Divergence Theorem . 25 2.2 Motion and Deformation . 27 2.3 The Comparison Motion . 32 2.4 The Fundamental Lemmas . 36 3 Mechanics of Continuous Media 39 3.1 The Classical Theories . 40 3.1.1 IdealFluids.......................... 40 3.1.2 ElasticSolids......................... 46 3.1.3 Inelastic Materials . 50 3.2 Theories with Microstructure . 54 3.2.1 Granular Solids . 54 3.2.2 Elastic Solids with Microstructure . 59 2 4 Mechanics of Mixtures 65 4.1 Motions and Comparison Motions of a Mixture . 66 4.1.1 Motions............................ 66 4.1.2 Comparison Fields . 68 4.2 Mixtures of Ideal Fluids . 71 4.2.1 Compressible Fluids . 71 4.2.2 Incompressible Fluids . 73 4.2.3 Fluids with Microinertia . 75 4.3 Mixture of an Ideal Fluid and an Elastic Solid . 83 4.4 A Theory of Mixtures with Microstructure . 86 5 Discontinuous Fields 91 5.1 Singular Surfaces . -

Principle of Virtual Work

Chapter 1 Principle of virtual work 1.1 Constraints and degrees of freedom The number of degrees of freedom of a system is equal to the number of variables required to describe the state of the system. For instance: • A particle constrained to move along the x axis has one degree of freedom, the position x on this axis. • A particle constrained to the surface of the earth has two degrees of freedom, longitude and latitude. • A wheel rotating on a fixed axle has one degree of freedom, the angle of rotation. • A solid body in free space has six degrees of freedom: a particular atom in the body can move in three dimensions, which accounts for three degrees of freedom; another atom can move on a sphere with the first particle at its center for two additional degrees of freedom; any other atom can move in a circle about the line passing through the first two atoms. No other independent motion of the body is possible. • N atoms moving freely in three-dimensional space collectively have 3N degrees of freedom. 1.1.1 Holonomic constraints Suppose a mass is constrained to move in a circle of radius R in the x-y plane. Without this constraint it could move freely over this plane. Such a constraint could be expressed by the equation for a circle, x2 + y2 = R2. A better way to represent this constraint is F (x; y) = x2 + y2 − R2 = 0: (1.1.1) 1 CHAPTER 1. PRINCIPLE OF VIRTUAL WORK 2 As we shall see, this constraint may be useful when expressed in differential form: @F @F dF = dx + dy = 2xdx + 2ydy = 0: (1.1.2) @x @y A constraint that can be represented by setting to zero a function of the variables representing the configuration of a system (e.g., the x and y locations of a mass moving in a plane) is called holonomic. -

Virtual Work

MEAM 535 Principle of Virtual Work Aristotle Galileo (1594) Bernoulli (1717) Lagrange (1788) 1. Start with static equilibrium of holonomic system of N particles 2. Extend to rigid bodies 3. Incorporate inertial forces for dynamic analysis 4. Apply to nonholonomic systems University of Pennsylvania 1 MEAM 535 Virtual Work Key Ideas (a) Fi Virtual displacement e2 Small Consistent with constraints Occurring without passage of time rPi Applied forces (and moments) Ignore constraint forces Static equilibrium e Zero acceleration, or O 1 Zero mass Every point, Pi, is subject to The virtual work is the work done by a virtual displacement: . e3 the applied forces. N n generalized coordinates, qj (a) Pi δW = ∑[Fi ⋅δr ] i=1 University of Pennsylvania 2 € MEAM 535 Example: Particle in a slot cut into a rotating disk Angular velocity Ω constant Particle P constrained to be in a radial slot on the rotating disk P F r How do describe virtual b2 Ω displacements of the particle P? b1 O No. of degrees of freedom in A? Generalized coordinates? B Velocity of P in A? a2 What is the virtual work done by the force a1 F=F1b1+F2b2 ? University of Pennsylvania 3 MEAM 535 Example l Applied forces G=τ/2r B F acting at P Q r φ θ m F G acting at Q P (assume no gravity) Constraint forces x All joint reaction forces Single degree of freedom Generalized coordinate, θ Motion of particles P and Q can be described by the generalized coordinate θ University of Pennsylvania 4 MEAM 535 Static Equilibrium Implies Zero Virtual Work is Done Forces Forces that do -

Towards Energy Principles in the 18Th and 19Th Century – from D’Alembert to Gauss

Towards Energy Principles in the 18th and 19th Century { From D'Alembert to Gauss Ekkehard Ramm, Universit¨at Stuttgart The present contribution describes the evolution of extremum principles in mechanics in the 18th and the first half of the 19th century. First the development of the 'Principle of Least Action' is recapitulated [1]: Maupertuis' (1698-1759) hypothesis that for any change in nature there is a quantity for this change, denoted as 'action', which is a minimum (1744/46); S. Koenig's contribution in 1750 against Maupertuis, president of the Prussian Academy of Science, delivering a counter example that a maximum may occur as well and most importantly presenting a copy of a letter written by Leibniz already in 1707 which describes Maupertuis' general principle but allowing for a minimum or maximum; Euler (1707-1783) heavily defended Maupertuis in this priority rights although he himself had discovered the principle before him. Next we refer to Jean Le Rond d'Alembert (1717-1783), member of the Paris Academy of Science since 1741. He described his principle of mechanics in his 'Trait´ede dynamique' in 1743. It is remarkable that he was considered more a mathematician rather than a physicist; he himself 'believed mechanics to be based on metaphysical principles and not on experimental evidence' [2]. Ne- vertheless D'Alembert's Principle, expressing the dynamic equilibrium as the kinetic extension of the principle of virtual work, became in its Lagrangian ver- sion one of the most powerful contributions in mechanics. Briefly Hamilton's Principle, denoted as 'Law of Varying Action' by Sir William Rowan Hamilton (1805-1865), as the integral counterpart to d'Alembert's differential equation is also mentioned. -

Leonhard Euler - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 14

Leonhard Euler - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 14 Leonhard Euler From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Leonhard Euler ( German pronunciation: [l]; English Leonhard Euler approximation, "Oiler" [1] 15 April 1707 – 18 September 1783) was a pioneering Swiss mathematician and physicist. He made important discoveries in fields as diverse as infinitesimal calculus and graph theory. He also introduced much of the modern mathematical terminology and notation, particularly for mathematical analysis, such as the notion of a mathematical function.[2] He is also renowned for his work in mechanics, fluid dynamics, optics, and astronomy. Euler spent most of his adult life in St. Petersburg, Russia, and in Berlin, Prussia. He is considered to be the preeminent mathematician of the 18th century, and one of the greatest of all time. He is also one of the most prolific mathematicians ever; his collected works fill 60–80 quarto volumes. [3] A statement attributed to Pierre-Simon Laplace expresses Euler's influence on mathematics: "Read Euler, read Euler, he is our teacher in all things," which has also been translated as "Read Portrait by Emanuel Handmann 1756(?) Euler, read Euler, he is the master of us all." [4] Born 15 April 1707 Euler was featured on the sixth series of the Swiss 10- Basel, Switzerland franc banknote and on numerous Swiss, German, and Died Russian postage stamps. The asteroid 2002 Euler was 18 September 1783 (aged 76) named in his honor. He is also commemorated by the [OS: 7 September 1783] Lutheran Church on their Calendar of Saints on 24 St. Petersburg, Russia May – he was a devout Christian (and believer in Residence Prussia, Russia biblical inerrancy) who wrote apologetics and argued Switzerland [5] forcefully against the prominent atheists of his time. -

Principle of Virtual Work

Principle of Virtual Work Degrees of Freedom Associated with the concept of the lumped-mass approximation is the idea of the NUMBER OF DEGREES OF FREEDOM. This can be defined as “the number of independent co-ordinates required to specify the configuration of the system”. The word “independent” here implies that there is no fixed relationship between the co- ordinates, arising from geometric constraints. Modelling of Automotive Systems 1 Degrees of Freedom of Special Systems A particle in free motion in space has 3 degrees of freedom z particle in free motion in space r has 3 degrees of freedom y x 3 If we introduce one constraint – e.g. r is fixed then the number of degrees of freedom reduces to 2. note generally: no. of degrees of freedom = no. of co-ordinates –no. of equations of constraint Modelling of Automotive Systems 2 Rigid Body This has 6 degrees of freedom y 3 translation P2 P1 3 rotation P3 . x 3 e.g. for partials P1, P2 and P3 we have 3 x 3 = 9 co-ordinates but the distances between these particles are fixed – for a rigid body – thus there are 3 equations of constraint. The no. of degrees of freedom = no. of co-ordinates (9) - no. of equations of constraint (3) = 6. Modelling of Automotive Systems 3 Formulation of the Equations of Motion Two basic approaches: 1. application of Newton’s laws of motion to free-body diagrams Disadvantages of Newton’s law approach are that we need to deal with vector quantities – force and displacement. thus we need to resolve in two or three dimensions – choice of method of resolution needs to be made. -

Learning the Virtual Work Method in Statics: What Is a Compatible Virtual Displacement?

2006-823: LEARNING THE VIRTUAL WORK METHOD IN STATICS: WHAT IS A COMPATIBLE VIRTUAL DISPLACEMENT? Ing-Chang Jong, University of Arkansas Ing-Chang Jong serves as Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Arkansas. He received a BSCE in 1961 from the National Taiwan University, an MSCE in 1963 from South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, and a Ph.D. in Theoretical and Applied Mechanics in 1965 from Northwestern University. He was Chair of the Mechanics Division, ASEE, in 1996-97. His research interests are in mechanics and engineering education. Page 11.878.1 Page © American Society for Engineering Education, 2006 Learning the Virtual Work Method in Statics: What Is a Compatible Virtual Displacement? Abstract Statics is a course aimed at developing in students the concepts and skills related to the analysis and prediction of conditions of bodies under the action of balanced force systems. At a number of institutions, learning the traditional approach using force and moment equilibrium equations is followed by learning the energy approach using the virtual work method to enrich the learning of students. The transition from the traditional approach to the energy approach requires learning several related key concepts and strategy. Among others, compatible virtual displacement is a key concept, which is compatible with what is required in the virtual work method but is not commonly recognized and emphasized. The virtual work method is initially not easy to learn for many people. It is surmountable when one understands the following: (a) the proper steps and strategy in the method, (b) the displacement center, (c) some basic geometry, and (d ) the radian measure formula to compute virtual displacements. -

Leonhard Euler's Elastic Curves Author(S): W

Leonhard Euler's Elastic Curves Author(s): W. A. Oldfather, C. A. Ellis and Donald M. Brown Source: Isis, Vol. 20, No. 1 (Nov., 1933), pp. 72-160 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The History of Science Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/224885 Accessed: 10-07-2015 18:15 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and The History of Science Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Isis. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.138.65.63 on Fri, 10 Jul 2015 18:15:50 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions LeonhardEuler's ElasticCurves (De Curvis Elasticis, Additamentum I to his Methodus Inveniendi Lineas Curvas Maximi Minimive Proprietate Gaudentes, Lausanne and Geneva, 1744). Translated and Annotated by W. A. OLDFATHER, C. A. ELLIS, and D. M. BROWN PREFACE In the fall of I920 Mr. CHARLES A. ELLIS, at that time Professor of Structural Engineering in the University of Illinois, called my attention to the famous appendix on elastic curves by LEONHARD EULER, which he felt might well be made available in an English translationto those students of structuralengineering who were interested in the classical treatises which constitute landmarks in the history of this ever increasingly important branch of scientific and technical achievement. -

Application of Principle of Virtual Work to Find Displacement in Statically Indeterminate Structures

CE474 – Structural Analysis II Application of Principle of Virtual Work to Find Displacement in Statically Indeterminate Structures Example: Find B , the vertical displacement at B. Consider flexural response only; assume EI is constant. First of all, we need to find the curvature distribution in this statically indeterminate to 1st degree propped‐ cantilever structure. Let’s treat the moment reaction at A as the redundant reaction and use method of consistent deformations (also known as compatibility method or flexibility method) to solve the system. + We can use the virtual force method to find and . That is, we first apply a tracer virtual unit moment A,15 A,MA at A and then convolve the resulting virtual bending moment distribution with the curvature distributions in the two simply supported beams loaded with real external force 15 kN and support reaction M A , respectively, to find the corresponding internal virtual strain energy results. Equating these to the respective external virtual work in each case we can find and . A,15 A,MA CE474 – Structural Analysis II Equating external virtual work to internal virtual strain energy Now requiring the compatibility condition that net slope change at A should be zero, we can find M A . Now that we have found the moment distribution in the propped cantilever when it loaded by 15 kN downward force at midspan point B, we can now find vertical displacement at B, B . We will do so using virtual force approach –aside: this method is also known as “dummy load” method or “unit load” method. We will find B using three different “virtual systems”. -

Virtual-Work-Based Optimization Design on Compliant Transmission Mechanism for Flapping-Wing Aerial Vehicles

Virtual-work-based Optimization Design on Compliant Transmission Mechanism for Flapping-wing Aerial Vehicles Chao Zhang, Claudio Rossi Wei He Julian Colorado Abstract—This paper presents a method for analysing and the literature [4], [5]. However, additional springs not only optimizing the design of a compliant transmission mechanism bring unneeded payloads, but also do not reduce joint friction for a flapping-wing aerial vehicle. Its purpose is of minimizing energy losses [6]. Recently, piezoelectric or electromagnetic the peak input torque required from a driving motor. In order to maintain the stability of flight, minimizing the peak input torque actuators are also introduced to couple with the mechanism is necessary. To this purpose, first, a pseudo-rigid-body model for driving flapping wings toward resonance [4], [7]—[11]. was built and a kinematic analysis of the model was carried out. However, neither piezoelectric nor electromagnetic actuators Next, the aerodynamic torque generated by flapping wings was are suitable for systems with a higher desired payload due to calculated. Then, the input torque required to keep the flight their high power requirements and limits in displacement and of the vehicle was solved by using the principle of virtual work. The values of the primary attributes at compliant joints (i.e., forces [4]. the torsional stiffness of virtual spring and the initial neutral Compared to the above spring mechanisms and piezoelectric angular position) were optimized. By comparing to a full rigid- or electromagnetic actuators, compliant mechanisms seem to body mechanism, the compliant transmission mechanism with be more attractive solutions. Such mechanisms are multi well-optimized parameters can reduce the peak input torque up functional structures which combine functions of mechanical to 66.0%. -

Virtual Work

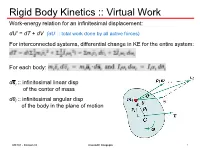

Rigid Body Kinetics :: Virtual Work Work-energy relation for an infinitesimal displacement: dU’ = dT + dV (dU’ :: total work done by all active forces) For interconnected systems, differential change in KE for the entire system: For each body: dsi̅ :: infinitesimal linear disp of the center of mass dθi :: infinitesimal angular disp of the body in the plane of motion ME101 - Division III Kaustubh Dasgupta 1 Rigid Body Kinetics :: Virtual Work Now, a̅ i ·ds̅ i is identical to (a̅ i )t ds̅ i αi :: angular accln θ̈i of the body (a̅ i )t :: component of a̅ i along tangent to the curve described by mass center of the body th Ri :: resultant force and couple acting on i body th MGi :: resultant couple acting on i body dθi :: dθi k Differential change in kinetic energy = Differential work done by the resultant forces and couples ME101 - Division III Kaustubh Dasgupta 2 Rigid Body Kinetics :: Virtual Work dU’ = dT + dV (dU’ :: total work done by all active forces) dV :: differential change in total Vg and Ve hi :: vertical distance of the center of mass mi above a convenient datum plane xi :: deformation of elastic member (spring of stiffness kj) of system (+ve for same dirn. of accn and disp) Direct relation between the accelerations and the active forces Virtual Work ME101 - Division III Kaustubh Dasgupta 3 Rigid Body Kinetics :: Virtual Work • Statics – Virtual work eqn • Kinetics • If a rigid body is in equilibrium • total virtual work of external forces acting on the body is zero for any virtual displacement of the body ME101 - Division -

Chapter 11: Virtual Work Goals and Objectives Introduce the Principle of Virtual Work

Chapter 11: Virtual Work Goals and Objectives Introduce the principle of virtual work Show how it applies to determining the equilibrium configuration of a series of pin-connected members Definition of Work Work of a force A force does work when it undergoes a displacement in the direction of the line of action. The work 푑푈 produced by the force 푭 when it undergoes a differential displacement 푑풓 is given by Work of a couple moment Incremental Displacement Rigid body displacement of P = translation of A + rotation about A Translation of A Incremental Displacement Rigid body displacement of P = translation of A + rotation about A Rotation about A dϴ Incremental Displacement Rigid body displacement of P = translation of A + rotation about A Translation of A + Rotation about A dϴ dϴ Definition of Work Work of couple ∴ The couple forces do no work during the translation 푑풓퐴 Work due to rotation Virtual Displacements A virtual displacement is a conceptually possible displacement or rotation of all or part of a system of particles. The movement is assumed to be possible, but actually does not exist. A virtual displacement is a first-order differential quantity denoted by the symbol 훿 (for example, 훿r and 훿θ. Principle of Virtual Work The principle of virtual work states that if a body is in equilibrium, then the algebraic sum of the virtual work done by all the forces and couple moments acting on the body is zero for any virtual displacement of the body. Thus, 훿푈 = 0 훿푈 = Σ 푭 ∙ 훿풖 + Σ 푴 ∙ 훿휽 = 0 For 2D: 훿푈 = Σ 푭 ∙ 훿풖 + Σ 푀 훿휃 = 0 Procedure for Analysis 1.