Ethnography Journal of Contemporary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS of LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS in HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 By

ON THE BEAT: UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS OF LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS IN HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 by Francesca A. Keesee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science Conflict Analysis and Resolution Master of Arts Conflict Resolution and Mediterranean Security Committee: ___________________________________________ Chair of Committee ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Graduate Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA University of Malta Valletta, Malta On the Beat: Understanding Portrayals of Law Enforcement Officers in Hip-hop Lyrics Since 2009 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master of Science at George Mason University and Master of Arts at the University of Malta by Francesca A. Keesee Bachelor of Arts University of Virginia, 2015 Director: Juliette Shedd, Professor School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia University of Malta Valletta, Malta Copyright 2016 Francesca A. Keesee All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to all victims of police brutality. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever grateful to my best friend, partner in crime, and husband, Patrick. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

Abstract Humanities Jordan Iii, Augustus W. B.S. Florida

ABSTRACT HUMANITIES JORDAN III, AUGUSTUS W. B.S. FLORIDA A&M UNIVERSITY, 1994 M.A. CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY, 1998 THE IDEOLOGICAL AND NARRATIVE STRUCTURES OF HIP-HOP MUSIC: A STUDY OF SELECTED HIP-HOP ARTISTS Advisor: Dr. Viktor Osinubi Dissertation Dated May 2009 This study examined the discourse of selected Hip-Hop artists and the biographical aspects of the works. The study was based on the structuralist theory of Roland Barthes which claims that many times a performer’s life experiences with class struggle are directly reflected in his artistic works. Since rap music is a counter-culture invention which was started by minorities in the South Bronx borough ofNew York over dissatisfaction with their community, it is a cultural phenomenon that fits into the category of economic and political class struggle. The study recorded and interpreted the lyrics of New York artists Shawn Carter (Jay Z), Nasir Jones (Nas), and southern artists Clifford Harris II (T.I.) and Wesley Weston (Lii’ Flip). The artists were selected on the basis of geographical spread and diversity. Although Hip-Hop was again founded in New York City, it has now spread to other parts of the United States and worldwide. The study investigated the biography of the artists to illuminate their struggles with poverty, family dysfunction, aggression, and intimidation. 1 The artists were found to engage in lyrical battles; therefore, their competitive discourses were analyzed in specific Hip-Hop selections to investigate their claims of authorship, imitation, and authenticity, including their use of sexual discourse and artistic rivalry, to gain competitive advantage. -

Examining the Role Hip-Hop Texts Play in Viewing the World

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Department of Middle-Secondary Education and Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Instructional Technology (no new uploads as of Technology Dissertations Jan. 2015) Fall 1-10-2014 Wordsmith: Examining the role hip-hop texts play in viewing the world Crystal LaVoulle Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/msit_diss Recommended Citation LaVoulle, Crystal, "Wordsmith: Examining the role hip-hop texts play in viewing the world." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/msit_diss/119 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Technology (no new uploads as of Jan. 2015) at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Technology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACCEPTANCE This dissertation, WORDSMITH: EXAMINING THE ROLE HIP-HOP TEXTS PLAY IN VIEWING THE WORLD, by CRYSTAL LAVOULLE, was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s Dissertation Advisory Committee. It is accepted by the committee members in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Philosophy, in the College of Education, Georgia State University. The Dissertation Advisory Committee and the student’s Department Chairperson, as representatives of the faculty, certify that this dissertation has met all standards of excellence and scholarship as determined by the faculty. The Dean of the College of Education concurs. _________________________________ _________________________________ Peggy Albers, Ph.D. Tisha Y. Lewis, Ph.D. Committee Chair Committee Member _________________________________ _________________________________ Kimberly Glenn, Ph.D. -

Drug Abuse Trends in the Cleveland Region OSAM Ohio Substance Abuse Monitoring Network

Surveillance of Drug Abuse Trends in the Cleveland Region OSAM Ohio Substance Abuse Monitoring Network Drug Abuse Trends in the Cleveland Region Regional Epidemiologist: Jennifer Tulli, MSW, LISW-S, LCDC III Data Sources for the Cleveland Region This regional report was based upon qualitative data collect- ed via focus group interviews. Participants were active and recovering drug users recruited from alcohol and other drug treatment programs in Cuyahoga, Lake, Lorain and Wayne counties. Data triangulation was achieved through compari- son of participant data to qualitative data collected from regional community professionals (treatment providers and law enforcement) via focus group interviews, as well as to data surveyed from the Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner’s Office, the Lake County Crime Lab and the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation (BCI) Richfield Crime Lab, which serves the Cleveland, Akron-Canton and Youngstown areas. In addition, data were abstracted from the National Forensic Laboratory Information System (NFLIS) which collects results from drug chemistry analyses conducted by state and local forensic laboratories across Ohio. All secondary data are OSAM Staff: summary data of cases processed from January through June 2016. In addition to these data sources, Ohio media outlets R. Thomas Sherba, PhD, MPH, LPCC were queried for information regarding regional drug abuse OSAM Principal Investigator for July through December 2016. Kathryn A. Coxe, MSW, LSW Note: OSAM participants were asked to report on drug use/knowl- OSAM Coordinator edge pertaining to the past six months prior to the interview; thus, current secondary data correspond to the reporting period of Jessica Linley, PhD, MSW, LSW participants. -

Back on the Prowl

OZONE MAGAZINE RANGE ROVER ALL WHITE LIKE HER TOE TIPS ALL WHITE LIKE HER TOE RANGE ROVER MAGAZINE OZONE YOUR FAVORITE RAPPER’S FAVORITE MAGAZINE THE ILLUSTRATION ISSUE: T.I. LIL Wayne scarface ANDRE 3000 & MORE T BACKRINA ON THE PROWL DEM FRANCHIZE BOYZ RICK ROSS |GREG STREET MAC-BONEY | OOOPS XVII | TAYDIZM And MUCH MORE! + OZONE WEST DEM HOODSTARZ SPRING 2008 STRONG ARM STEADY Cino: Organized Grind YOUNG L OF THE PACK OZONE MAG // YOUR FAVORITE RAPPER’S FAVORITE MAGAZINE DEM FRANCHIZE BOYZ + TRINA | CHERI DENNIS OZONE WEST GREG STREET | RICK ROSS DEM HOODSTARZ THE FIRST ANNUAL ILLUSTRATION ISSUE STRONG ARM STEADY MAC-BONEY | OOOPS | TAYDIZM AND MUCH MORE! Cino: Organized Grind YOUNG L OF THE PACK 8 // OZONE WEST 2 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 8 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 0 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric N. Perrin ASSOCIATE EDITOR // Maurice G. Garland ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden illustrations ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul 63 T.I. SPECIAL EDITION EDITOR // Jen McKinnon 65 PIMP C MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad Sr. 68 50 CENT LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. 67 JUVENILE 66 SCARFACE SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Adero Dawson 70 LIL WAYNE ADMINISTRATIVE // Kisha Smith 64 RICK ROSS INTERN // Kari Bradley 62 C-MURDER CONTRIBUTORS // Bogan, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, Cierra Middlebrooks, Destine 69 ANDRE 3000 Cajuste, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, 71 BOB MARLEY Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, K.G. -

Petey Pablo Is Crazy

Call your cable provider to request MTV Jams Comcast Cable 1-800-COMCAST www.comcast.com Atlanta, GA Comcast ch. 167 Augusta, GA Comcast ch. 142 Charleston, SC Comcast ch. 167 Chattanooga, TN Comcast ch. 142 Ft. Laud., FL Comcast ch. 142 Hattiesburg, MS Comcast ch. 142 Houston, TX Comcast ch. 134 Jacksonville, FL Comcast ch. 470 Knoxville, TN Comcast ch. 142 Little Rock, AR Comcast ch. 142 Miami, FL Comcast ch. 142 Mobile, AL Comcast ch. 142 Montgomery, AL Comcast ch. 304 Naples, FL Comcast ch. 142 Nashville, TN Comcast ch. 142 Panama City, FL Comcast ch. 142 Richmond, VA Comcast ch. 142 Savannah, GA Comcast ch. 142 Tallahassee, FL Comcast ch. 142 Charter Digital 1-800-GETCHARTER www.charter.com Birmingham, AL Charter ch. 304 Dallas, TX Charter ch. 227 Greenville, SC Charter ch. 204 Ft. Worth, TX Charter ch. 229 Spartanburg, SC Charter ch. 204 Grande Communications www.grandecom.com Austin, TX Grande ch. 185 PUBLISHERS: Julia Beverly (JB) Chino EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Julia Beverly (JB) MUSIC REVIEWS: ADG, Wally Sparks CONTRIBUTORS: Bogan, Cynthia Coutard, Dain Bur- roughs, Darnella Dunham, Felisha Foxx, Felita Knight, Iisha Hillmon, Jaro Vacek, Jessica Koslow, J Lash, Katerina Perez, Keith Kennedy, K.G. Mosley, King Yella, Lisa Cole- man, Malik “Copafeel” Abdul, Marcus DeWayne, Matt Sonzala, Maurice G. Garland, Natalia Gomez, Ray Tamarra, Rayfield Warren, Rohit Loomba, Spiff, Swift SALES CONSULTANT: Che’ Johnson (Gotta Boogie) LEGAL AFFAIRS: Kyle P. King, P.A. (King Law Firm) STREET REPS: Al-My-T, B-Lord, Bill Rickett, Black, Bull, Cedric Walker, Chill, Chilly C, Control- ler, Dap, Delight, Dereck Washington, Derek Jurand, Dwayne Barnum, Dr. -

PLACES to GO, PEOPLE to SEE THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 25 FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 26 SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 27 the Regulars

Entertainment & Culture at Vanderbilt SEPTEMBER 24—SEPTEMBER 30, 2008 NO. 17 YOU MAY THINK HE’S “DANGEROUS.” WE THINK HE’S “DOPE.” Jim and Pam? Andy and Angela + Dwight? We recap “The Offi ce” drama on page 3. Go on. Open Pandora’s Box (on page 4). Get in The Game on page 5. PLACES TO GO, PEOPLE TO SEE THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 25 FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 26 SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 27 The Regulars Chris Knight with Ricky Young — Exit/In The Expendables with Rebelution and OPM —Mercy Eclipse — Mercy Lounge THE RUTLEDGE Chris Knight has been on the up-and-up for years now, releasing Lounge/Cannery Ballroom Want to hear the greatest hits of one of the greatest bands of our 410 Fourth Ave. S. 37201 fi ve albums and garnering love from a host of music critics. He’s Rockers The Expendables stop by Nashville during their fall tour. Best known for time? Eclipse is making that a reality with their tribute to Pink Floyd. 782-6858 been compared to Cash and Springsteen, and he’s only getting their reggae-infl uenced surf rock and near-constant touring, The Expendables Get ready to visit the dark side of the moon. ($7, 9 p.m.) better. Admission is a small price to pay to see this auteur. ($10, should provide a relaxing but entertaining evening. Openers include Santa MERCY LOUNGE/CANNERY 9 p.m.) Barbara group Rebelution and fellow Californains OPM. ($12 advance/$15 day Keith Urban — Grand Ole Opry BALLROOM of show, 9 p.m.) Come see this Aussie crooner play his top charting songs in the show 1 Cannery Row 37203 Good Souls — Sambuca that helped country music get its start. -

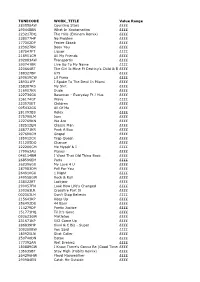

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 280558AW

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 280558AW Counting Stars ££££ 290448BN What In Xxxtarnation ££££ 223217DQ The Hills (Eminem Remix) ££££ 238077HP No Problem ££££ 177302DP Fester Skank ££££ 223627BR Been You ££££ 187547FT Liquor ££££ 218951CM All My Friends ££££ 292083AW Transportin ££££ 290741BR Live Up To My Name ££££ 220664BT The Girl Is Mine Ft Destiny's Child & Brandy££££ 188327BP 679 ££££ 290619CW Lil Pump ££££ 289311FP I Spoke To The Devil In Miami ££££ 258307KS My Shit ££££ 216907KR Dude ££££ 222736GU Baseman - Everyday Ft J Hus ££££ 236174GT Wavy ££££ 223575ET Children ££££ 095432GS All Of Me ££££ 281093BS Rolex ££££ 275790LM Ispy ££££ 222769KN We Are ££££ 182512EN Classic Man ££££ 288771KR Peek A Boo ££££ 297690CM Gospel ££££ 185912CR Trap Queen ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 222206GM Me Myself & I ££££ 179963AU Planes ££££ 048114BM I Want That Old Thing Back ££££ 268596EM Paris ££££ 262396GU My Love 4 U ££££ 287983DM Fall For You ££££ 264910GU 1 Night ££££ 249558GW Rock & Roll ££££ 238022ET Lockjaw ££££ 290057FN Look How Life's Changed ££££ 230363LR Crossfire Part Iii ££££ 002363LM Don't Stop Believin ££££ 215643KP Keep Up ££££ 256492DU 44 Bars ££££ 114279DP Poetic Justice ££££ 151773HQ Til It's Gone ££££ 093623GW Mistletoe ££££ 231671KP 502 Come Up ££££ 286839HP 6ixvi & C Biz - Super ££££ 309350BW You Said ££££ 180925LN Shot Caller ££££ 250740DN Detox ££££ 177392AN Wet Dreamz ££££ 180889GW I Know There's Gonna Be (Good Times)££££ 135635BT Stay High (Habits Remix) ££££ 264296HW Floyd Mayweather ££££ 290984EN Catch Me Outside ££££ 191076BP -

Digital Booklet

01 INTRO 02 LAX FILES 03 STATE OF EMERGENCY feat. Ice Cube 04 BULLETPROOF DIARIES feat. Raekwon 05 MY LIFE feat. Lil Wayne 06 MONEY 07 CALI SUNSHINE feat. Bilal 08 YA HEARD feat. Ludacris 09 HARD LIQUOR (INTERLUDE) 10 HOUSE OF PAIN 11 GENTLEMAN’S AFFAIR feat. Ne-Yo 12 LET US LIVE feat. Chrisette Michelle 13 TOUCHDOWN feat. Raheem DeVaughn 14 ANGEL feat. Common 15 NEVER CAN SAY GOODBYE feat. Latoya Williams 16 DOPE BOYS feat. Travis Barker 17 GAME’S PAIN feat. Keyshia Cole 18 LETTER TO THE KING feat. Nas 19 OUTRO thisizgame.com Geffen Records. 2220 Colorado Ave., comptongame.com Santa Monica, CA 90404. Manufactured and distributed in the United States myspace.com/thegame by Universal Music Distribution. p 2008 Geffen Records. All rights reserved. Unauthorized duplication is a violation of applicable laws. Bulletproof Diaries feat. Raekwon (J. Taylor, C. Woods, D. Drew) Produced by: Jellyroll ณ Published by: BabyGame/Sony ATV Songs LLC(BMI)PicoPride Intro Publishing(BMI)/Prince Jaibari (E. Simmons, E. Pope) Publishing(BMI)/Denver St. Publishing(BMI) Produced by: Ervin”EP” Pope ณ Prayer by: DMX Keyboards by: 1500 or Nothin’, Ervin “EP” Pope Recorded by: Geoff Gibbs @ Encore Studios, Bass Guitar: William “kiddFLYY” Taylor Burbank, CA ณ Mixed by: Steve “B” Baughman @ Recorded by: Geoff Gibbs at Encore Studios, Pacifique Studios, N. Hollywood, CA ณ As- Burbank, CA and Sam Kalandjian at Pacifique sisted by: Samuel Kalandjian & Chris Doremus Studios, N. Hollywood, CA ณ Mixed by: Steve “B” Baughman at Pacifique Studios, N. Hollywood, CA Assisted by: Samuel Kalandjian & Chris Doremus LAX Files (J. -

The Beacon, August 29, 2008 Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons The aP nther Press (formerly The Beacon) Special Collections and University Archives 8-29-2008 The Beacon, August 29, 2008 Florida International University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/student_newspaper Recommended Citation Florida International University, "The Beacon, August 29, 2008" (2008). The Panther Press (formerly The Beacon). 180. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/student_newspaper/180 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and University Archives at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aP nther Press (formerly The Beacon) by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Forum for Free Student Expression at Florida International University Vol. 21, Issue 9 www.fi usm.com August 29, 2008 COUNTRY CLUB TURN OFF THE LIGHT GONE NUTS FOOTBALL RETURNS International students united Old schedule would save power Alumni go on comedy tour Golden Panthers take on Jayhawks AT THE BAY PAGE 3 OPINION PAGE 4 LIFE! PAGE 5 SPORTS PAGE 8 Tough times necessitate new GI Bill JULIO MENACHE plies. Servicemen can also Asst. News Director transfer unused benefits to their spouses and children. IDENTITY Sergeant Nathaniel Under the old GI Bill, Chapman is used to having soldiers needed to pay a bombs dropping all around $1,200 enrollment fee at CRISIS him. What he didn’t expect the beginning of their ser- was to have a “bomb” drop vice. Veterans would then on him back home. have 10 years after leaving The young FIU gradu- active duty to be eligible ate student, who just trans- for aid.