The Musical Basis of Verse, a Scientific Study of the Principles of Poetic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lots to Get Excited About

WEDNESDAY, 11TH NOVEMBER 2015 EBN EUROPEAN BLOODSTOCK NEWS FOR MORE INFORMATION: TEL: +44 (0) 1638 666512 • FAX: +44 (0) 1638 666516 • [email protected] • WWW.BLOODSTOCKNEWS.EU BLOODSTOCK WORLD | STALLION NEWS | RACING ROUND-UP | STAKES FIELDS TODAY’S HEADLINES SALES TALK OBITUARY TATTERSALLS IRELAND PAT EDDERY EBN Sales Talk Click here to The eleven-time Champion Jockey Pat Eddery, who rode more is brought to contact IRT, or than 4,600 winners, including 14 Classics, during his 36-year you by IRT visit www.irt.com career, has died. He was 63 and had been suffering ill health for some time. Born in County Kildare in 1952, he was apprenticed to Seamus RAHINSTOWN’S PRESENTING McGrath and Frenchie Nicholson, rode his first winner in 1969, and was Champion jockey for the first time in 1974 – and for the next COLT TOPS FIRST FOAL SESSION three seasons – and for the last time in 1996. Among the many A €52,000 son of Presenting, who was bought by the County top-class horses he rode were household names such as Grundy, Clare-based Garrynacurra Stud, held sway as the focus switched Pebbles, Sadler’s Wells, Rainbow Quest, El Gran Senor, Warning to the foal market at Tattersalls Ireland November National Hunt and Zafonic, while his four wins in the Gr.1 Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe Sale. included his memorable 1986 triumph on the great Dancing On the first of four days given over to foals, those buying with a Brave. After retiring from race riding in 2003, he took up training view to resell were out in force, as they looked to stockpile future and saddled Hearts Of Fire to Gr.1 victory in Italy in 2009. -

(IRE), Blue De Vega

The Duke of York Clipper Logistics Stakes Acapulco (USA), Ardhoomey (IRE), Baccarat (IRE), Blue de Vega (GER), Brando (GB), Caravaggio (USA), Cheikeljack (FR), Comicas (USA), Cotai Glory (GB), Dancing Star (GB), Danzeno (GB), Easton Angel (IRE), Final Venture (GB), Gracious John (IRE), Gravity Flow (IRE), Growl (GB), Jungle Cat (IRE), Kimberella (GB), Lancelot du Lac (ITY), Librisa Breeze (GB), Magical Memory (IRE), Mobsta (IRE), Mokarris (USA), Mr Lupton (IRE), Nameitwhatyoulike (GB), Orion's Bow (GB), Painted Cliffs (IRE), Quiet Reflection (GB), Raucous (GB), Smash Williams (IRE), Suedois (FR), Tasleet (GB), The Tin Man (GB), Tupi (IRE), Washington DC (IRE), Yalta (IRE) The Betfred Dante Stakes Across Dubai (GB), Apex King (IRE), Atty Persse (IRE), Auckland (IRE), Azam (GB), Barney Roy (GB), Belgravia (IRE), Benbatl (GB), Best of Days (GB), Best Solution (IRE), Bin Battuta (GB), Brutal (IRE), Call To Mind (GB), Capri (IRE), Churchill (IRE), Cliffs of Moher (IRE), Contrapposto (IRE), Cracksman (GB), Crowned Eagle (GB), Crystal Ocean (GB), Dhajeej (IRE), Diodorus (IRE), Douglas Macarthur (IRE), Dubai Sand (IRE), Elucidation (IRE), Elyaasaat (USA), Eminent (IRE), Emmaus (IRE), Ensign (GB), Escobar (IRE), Exemplar (IRE), Fibonacci (GB), Finn McCool (IRE), Forest Ranger (IRE), Frankuus (IRE), Frontispiece (GB), Galilean (IRE), Harlow (GB), Inca Gold (IRE), Itsakindamagic (GB), Karawaan (IRE), Lancaster Bomber (USA), Latin Beat (IRE), Law And Order (IRE), Leshlaa (USA), Lethal Impact (JPN), Manchego (GB), Marine One (GB), Middle Kingdom (USA), -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Newsletter Winter 2019

Newsletter Winter 2019 “Telescope” by Grace. THE SHADE OAK NEWSLETTER: 2020 SEASON This is the sort of winter day I love: crisp, dry, the sun rising low in the sky and the fields and hedges glistening with dew as they invite the thrilling chase that surely awaits me and my trusty charge, Sir Francis. So, why, you might very well ask (as I did myself not five minutes ago), am I locked in the loo with just an ipad for company? “That’s where most people read it so that’s where you can write it,” my lovely wifie kindly explained. So here I am, poised to bring you informative information and insightful insights into stud life, stallions, breeding and anything else that comes into my head so that I can produce sufficient words to earn early release, aided only by my trusty assistant who sits poised at the other end of an email connection ready to dig up some relevant statistic I can’t quite call to mind or remind me of the odd fact that I asked him to make a note of for just this moment. So here, just so long as the broadband doesn’t go down, is the annual Shade Oak Newsletter… THE SEARCH FOR A STALLION For the second year running we have no news of a new both Telescope and Dartmouth and a great trainer of stallion arriving at Shade Oak for the forthcoming season. I middle-distance horses, made the dreadful mistake of realise that breeders are often excited at the thought of using running him in a 10 furlong Group 1 rather than tackling a new stallion. -

School-Days of Eminent Men. Sketches of the Progress of Education

- ALBERT R. MANN LIBRARY New York State Colleges of Agriculture and Home Economics Cornell University rnel1 University Library • * »»-. -. £? LA 637.7.T58 1860 School-days of eminent men.Sketches of 3 1924 013 008 408 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924013008408 SCHOOLrDAYS OF EMINENT MEN. i. SKETCHES OF THE PROGRESS OF EDUCATION IN ENGLAND, FROM THE REIGN OF KING ALFRED TO THAT OF QUEEN VICTORIA. EARLY LIVES OF CELEBRATED BRITISH AUTHORS, PHILOSO- PHERS AND POE^S, INVENTORS AND DISCOVERERS, DIVINES, ^EROES, ; STATESMEN AND JOHN TIMBS, F.S.A., iOTHoa or "ooaio£iTiE3 or London," "things not oene&au.t known," mo. KKOM THE LONDON EDITION. COLUMBUS: FOLIiETT, FOSTER AND COMPANY. MDCCOLX. I«" LA FOLLETT, FOSTER & CO., Printers, Stereotypers, Binders and Publishers, COLUMBUS , OHIO. TO THE HEADER. To our admiration of true greatness naturally succeeds some curiosity as to the means by which such distinction has been attained. The subject of " the School-days of Eminent Persons," therefore, promises an abundance of striking incident, in the early buddings of genius, and formation of character, through which may be gained glimpses of many of the hidden thoughts and secret springs by which master-minds have moved the world. The design of the present volume may be considered an ambitious one to be attempted within so limited a compass ; but I felt the incontestible facility of producing a book brimful of noble examples of human action and well-directed energy, more especially as I proposed to gather my materials from among the records of a country whose cultivated people have advanced civilization far beyond the triumphs of any nation, an- cient or modern. -

Adultery in Early Stuart England

Veronika Christine Pohlig ___________________________ Adultery in Early Stuart England ________________________________________ Dissertation am Fachbereich Philosophie und Geisteswissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin 2009 Erstgutachterin: Frau Prof. Dr. Sabine Schülting Zweitgutachter: Herr Prof. Dr. Dr. Russell West-Pavlov Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 03.07.2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to take this opportunity to thank Prof. Ann Hughes, whose enlightening undergraduate seminar at Keele University taught me the fundamentals of historic research, and first sparked my interest in matters of gender and deviance, thus laying the basis for this project. I wish to express my gratitude towards the Graduiertenkolleg Codierung von Gewalt im medialen Wandel for giving me the opportunity to work with a number of amazing individuals and exchange ideas across disciplinary boundaries, and also for providing the financial means to make travelling in order to do research for this project possible. Special thanks goes out to the helpful staff at Gloucestershire Archives. Above all, I am greatly indebted to Prof. Sabine Schülting for providing the warm intellectual home in which this project could thrive, and for blending munificent support with astute criticism. I am most grateful to have benefited from her supervision. I wish to extend my most heartfelt thanks to Maggie Rouse, Sabine Lucia Müller, Anja Schwarz, Judith Luig, and to Kai Wiegandt for their insightful comments on various parts of this dissertation in various stages, but, more importantly, for unerring support and motivation. These were also given most generously by my brother-in-law, Matthias Pohlig, who read the manuscript with a keen historian's eye and provided invaluable feedback at a crucial stage of its genesis. -

Qipco British Champions Day Media Guide Qipco British Champions Day Media Guide

QIPCO British Champions Day Ascot Racecourse | Saturday 17th October Media Guide QIPCO BRITISH CHAMPIONS DAY MEDIA GUIDE QIPCO BRITISH CHAMPIONS DAY MEDIA GUIDE CONTENTS QIPCO BRITISH CHAMPIONS DAY 3 Race Day Programme RACE DAY PROGRAMME 4 Foreword by Rod Street 1.20PM QIPCO BRITISH CHAMPIONS LONG DISTANCE CUP (GROUP 2) NO PENALTIES, 3-y-o and up, 1 mile and 7 furlongs 209yds, round course. 5 Introduction by HH Sheikh Hamad bin Abdullah Al Thani 6 Ten Top Winners On QIPCO British Champions Day 1.55PM QIPCO BRITISH CHAMPIONS SPRINT STAKES (GROUP 1) 3-y-o and up, 6 furlongs (1200 metres), straight course. 8 QIPCO British Champions Day In Numbers 2.30PM QIPCO BRITISH CHAMPIONS FILLIES & MARES STAKES (GROUP 1) 10 The QIPCO British Champions Long Distance Cup 3-y-o and up, 1 mile and 3 furlongs 211yds, round course. 15 The QIPCO British Champions Sprint Stakes 3.05PM QUEEN ELIZABETH II STAKES (SPONSORED BY QIPCO) (GROUP 1) 3-y-o and up, 1 mile (1600) metres, straight course. 20 The QIPCO British Champions Fillies & Mares Stakes 25 The Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (sponsored by QIPCO) 3.40PM QIPCO CHAMPION STAKES (GROUP 1) 3-y-o and up, 1 mile and 2 furlongs (2000 metres), round course. 30 The QIPCO Champion Stakes 4.15PM BALMORAL HANDICAP (SPONSORED BY QIPCO) 36 The Balmoral Handicap (sponsored by QIPCO) 3-y-o and up, 1 mile (1600 metres), straight course. 39 Records of winning jockeys on QIPCO British Champions Day *all timings subject to change 41 Records of winning trainers on QIPCO British Champions Day 43 Background to QIPCO British Champions -

BAY FILLY (13) Foaled 17Th October 2019

25/01/2021 https://www.arion.co.nz/PrintReport.aspx?FileName=/files/TDN/00WildwoodDancer(AUS)190_Pedigreesreport-0_132560307712390941.html BAY FILLY (13) Foaled 17th October 2019 Sire Northern Meteor Encosta de Lago Fairy King DEEP FIELD Explosive Fappiano 2010 Listen Here Elusive Quality Gone West Announce Military Plume Dam Exceed and Excel Danehill Danzig WILDWOOD DANCER Patrona Lomond 2010 Punchess Two Punch Mr. Prospector Pailleron Majestic Light DEEP FIELD (AUS) (Bay 2010-Stud 2015). 5 wins to 1200m, VRC Tab.com.au S., Gr.2. Sire of 243 rnrs, 141 wnrs, inc. SW Cosmic Force (ATC Roman Consul S., Gr.2), Xilong, Dig Deep, Portland Sky, Isotope, Riddle Me That, Fituese, SP Aysar, Marchena, Sweet Reply, Hawker Hurricane, Three Beans - Divine Regulus (H.K.), Deep Speed, Kavak, Nitrous - Circuit Seven (H.K.), Big Parade, Chat, Deep Sea - All in Mind (H.K.), Quantum Mechanic, Spaceboy, etc. 1st dam WILDWOOD DANCER (AUS 2010f. by Exceed and Excel) 2 wins at 1000m, 1200m.(trainer: Luke Oliver).(covered in 2020 by All Too Hard) .2012 William Inglis Sydney Easter Yearling Sale; L Oliver, Vic; Sold $80,000. 2016 Magic Millions National Broodmare Sale; James Harron B/stock, NSW; Sold $190,000. Sister to Exclaim'n'exclude, half- sister to Fantene. This is her fourth foal. Her third foal is a 2YO. Dam of two named foals, both raced, inc:- Lady Huntsmen (AUS 2016f. by Shooting to Win) Placed at 3 in 2019-20.(trainer: T Haddy).2018 William Inglis Classic Yearling Sale; Anthony Freedman Racing / De Burgh Equine, Vic; Sold $10,000. Kasami (AUS 2017f. -

Guidelines for Photocopying

Guidelines for Photocopying Permission to make photocopies of or to reproduce by any other mechanical or electronic means in whole or in part any page, illustration or activity in this product is granted only to the original pur- chaser and is intended for noncommercial use within a church or other Christian organization. None of the material in this product may be reproduced for any commercial promotion, advertising or sale of a product or service or to share with any other persons, churches or organizations. Sharing of the ma- terial in this book with other churches or organizations not owned or controlled by the original purchaser is also prohibited. All rights reserved. Editorial Staff Senior Managing Editor, Sheryl Haystead • Senior Editor, Debbie Barber • Editor, Deborah Sourgen • Editorial Team, Mary Davis, Janis Halverson, Lisa Pham, Karen McGraw • Designer, Annette M. Chavez Founder, Dr. Henrietta Mears • Publisher, William T. Greig • Senior Consulting Publisher, Dr. Elmer L. Towns • Senior Editor, Biblical and Theological Content, Dr. Gary S. Greig Scripture quotations are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. All rights reserved. © 2011 Gospel Light, Ventura, CA 93006. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. How to Use Little KidsTime A few children, two leaders or teachers If you teach with only one other person, follow these simple steps: 1. Read “Discovering God’s Love Overview” on page 7 to get a clear view of what this course is about. 2. Look at “Advice & Answers for Schedule Planning” on pages 9-11. -

Casse, Mott, Pletcher & Ward Among Strong US- Trained Royal Ascot

Ascot Racecourse Media Release for immediate release, Wednesday, April 26, 2017 Casse, Mott, Pletcher & Ward among strong US- trained Royal Ascot challenge Exciting entries are revealed today for the eight Group One races staged at Royal Ascot, which takes place from Tuesday, June 20 through to Saturday, June 24. A very strong US-trained challenge is in prospect, with representation in five of the eight races. All eight G1 Royal Ascot contests are part of the QIPCO British Champions Series, with the King's Stand Stakes and Diamond Jubilee Stakes also involved in the Global Sprint Challenge. £600,000 Queen Anne Stakes - One Mile straight, Tuesday, June 20 (2.30pm) - 33 entries Royal Ascot opens with the mile G1 Queen Anne Stakes for four-year-olds and upwards. The 33 entries include leading European lights Minding (Aidan O'Brien IRE), who capped a superb 2016 by taking the Queen Elizabeth II Stakes sponsored by QIPCO at Ascot on QIPCO British Champions Day in October, as well as last year's QIPCO 2000 Guineas and St James's Palace Stakes hero Galileo Gold (Hugo Palmer). A US-trained challenge could come from four-year-old War Front colt American Patriot (Todd Pletcher USA), who put up a career-best effort last time out when winning the G1 Maker's 46 Mile on turf at Keeneland on April 14, and three-time G1 scorer Miss Temple City (Graham Motion USA), who may line up at her third Royal Ascot following fourth in the G1 Coronation Stakes in 2015 and occupying the same finishing position in last year's G2 Duke of Cambridge Stakes. -

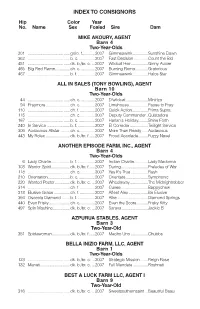

TO CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No

INDEX TO CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No. Name Sex Foaled Sire Dam MIKE AKOURY, AGENT Barn 4 Two-Year-Olds 201 ................................. ......gr/ro. f............2007 Gimmeawink ..............Sunshine Dawn 362 ................................. ......b. c................2007 Fast Decision .............Count the Bid 451 ................................. ......dk. b./br. c. ...2007 Wildcat Heir................Ginny Auxier 465 Big Red Flame..............ch. c. .............2007 Burning Roma............Gratorious 467 ................................. ......b. f. ................2007 Gimmeawink ..............Halos Star ALL IN SALES (TONY BOWLING), AGENT Barn 10 Two-Year-Olds 44 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2007 D'wildcat.....................Miniriza 94 Praymore.......................ch. c. .............2007 Limehouse..................Pause to Pray 110 ................................. ......ch. f. ..............2007 Quick Action...............Prima Supra 115 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2007 Deputy Commander..Quistadora 167 ................................. ......b. c................2007 Harlan's Holiday.........Shine Forth 240 In Service ......................b. f. ................2007 El Corredor.................Twilight Service 306 Audacious Allstar .........ch. c. .............2007 More Than Ready......Audacious 443 My Rolex .......................dk. b./br. f......2007 Proud Accolade.........Fuzzy Navel ANOTHER EPISODE FARM, INC., AGENT Barn 4 Two-Year-Olds 6 Lady Charlie..................b. -

HORSE in TRAINING, Consigned by Lilly Hall Farm (E. De Giles) the Property of a Partnership Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Wall Box Z, Box 567

HORSE IN TRAINING, consigned by Lilly Hall Farm (E. de Giles) the Property of a Partnership Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Wall Box Z, Box 567 Danzig (USA) War Front (USA) 388 (WITH VAT) Declaration of War Starry Dreamer (USA) (USA) Rahy (USA) ORANGE SUIT Tempo West (USA) (IRE) Tempo (USA) (2015) Northern Dancer Sadler's Wells (USA) A Bay Gelding Guantanamera (IRE) Fairy Bridge (USA) (2004) Darshaan Bluffing (IRE) Instinctive Move (USA) Has been seen to Crib-Bite and Wind-Suck. Has had a soft palate operation. ORANGE SUIT (IRE): won 2 races at 2 and 4 years, 2019 and £15,405 and placed 5 times. Highest BHA rating 82 (Flat) Latest BHA rating 68 (Flat) (prior to compilation) TURF 12 runs 2 wins 4 pl £12,988 F - G 6f - 1m 2f 37y ALL WEATHER 6 runs 1 pl £2,417 1st Dam GUANTANAMERA (IRE), unraced; dam of five winners from 6 runners and 6 foals of racing age viz- SIMPLE VERSE (IRE) (2012 f. by Duke of Marmalade (IRE)), won 6 races at 3 and 4 years and £965,617 including Qipco British Champions Fillies/Mare Stakes, Ascot, Gr.1, Ladbrokes St Leger Stakes, Doncaster, Gr.1, DFS Park Hill Stakes, Doncaster, Gr.2 and Markel Insurance Lillie Langtry Stakes, Goodwood, Gr.3, placed 6 times including second in Jockey Club Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.2, Betway Yorkshire Cup, York, Gr.2 and third in Qipco British Champions Long Distance Cup, Ascot, Gr.2. EVEN SONG (IRE) (2013 f. by Mastercraftsman (IRE)), won 2 races at 2 and 3 years and £127,364 including Ribblesdale Stakes, Ascot, Gr.2, placed twice including third in Tweenhills Pretty Polly Stakes, Newmarket, L.