Tasmania - the Wilderness Isle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tasmania: Birds & Mammals 5 ½ -Day Tour

Bellbird Tours Pty Ltd PO Box 2008, BERRI SA 5343 AUSTRALIA Ph. 1800-BIRDING Ph. +61409 763172 www.bellbirdtours.com [email protected] Unique and unforgettable nature experiences! Tasmania: birds & mammals 5 ½ -day tour 15-20 Nov 2021 Australia’s mysterious island state is home to 13 Tasmanian Thornbill and Scrubtit, as well as the beautiful endemic birds as well as some unique mammal Swift Parrot. Iconic mammals include Tasmanian Devil, species. Our Tasmania: Birds & Mammals tour Platypus and Echidna. Add wonderful scenery, true showcases these wonderful birding and mammal wilderness, good food and excellent accommodation, often highlights in 5 ½ fabulous days. Bird species include located within the various wilderness areas we’ll be visiting, Forty-spotted Pardalote, Dusky Robin, 3 Honeyeaters, and you’ll realise this is one tour not to be missed! The tour Yellow Wattlebird, Tasmanian Native-Hen, Black commences and ends in Hobart, and visits Bruny Island, Mt Currawong, Green Rosella, Tasmanian Scrubwren, Wellington and Mt Field NP. Join us in 2021 for an unforgettable experience! Tour starts: Hobart, Tasmania Price: AU$3,799 all-inclusive (discounts available). Tour finishes: Hobart, Tasmania Leader: Andrew Hingston Scheduled departure & return dates: Trip reports and photos of previous tours: • 15-20 November 2021 http://www.bellbirdtours.com/reports Questions? Contact BELLBIRD BIRDING TOURS : READ ON FOR: • Freecall 1800-BIRDING • Further tour details • Daily itinerary • email [email protected] • Booking information Tour details: Tour starts & finishes: Starts and finishes in Hobart, Tasmania. Scheduled departure and return dates: Tour commences with dinner on 15 November 2021. Please arrive on or before 15 November. -

Australia: Tasmania and the Orange- Bellied Parrot 24 – 29 October 2020 24 – 29 October 2021

AUSTRALIA: TASMANIA AND THE ORANGE- BELLIED PARROT 24 – 29 OCTOBER 2020 24 – 29 OCTOBER 2021 The handsome Orange-bellied Parrot is the primary target on this tour. www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | ITINERARY Australia: Tasmania and the Orange-bellied Parrot Adjoined to the mainland until the end of the last glacial period about ten thousand years ago, Tasmania is both geographically and genetically isolated from Australia. Through the millennia this island has developed its own unique set of plants and animals, including twelve avian endemics that include Forty-spotted Pardalote, Green Rosella, and Strong-billed Honeyeater. Beyond the endemics Tasmania also harbors several species which winter on the mainland and breed on Tasmania, such as Swift Parrot and Orange-bellied Parrot. These two breeding endemics are globally Critically Endangered (IUCN) and major targets on this tour. Forty-spotted Pardalote is one of the Tasmanian endemics we will target on this tour. Our search for the endemics and breeding specialties of Tasmania is set within a stunning backdrop of rugged coastlines, tall evergreen sclerophyll forests, alpine heathlands, and cool temperate rainforests, undoubtedly enriching our experience here. In addition, due to the lack of foxes many marsupials are notably more numerous in Tasmania, and we should be able to observe several of these unique animals during our stay. For those wishing to continue exploring Australia, this tour can be combined with our set of Australia tours: Australia: from the Outback to the Wet Tropics, Australia: Top End Birding, and Australia: Southwest Specialties. All four Australia tours could be combined. We can also arrange other extensions (e.g., sightseeing trips to Sydney, Uluru, etc., and pelagic trips). -

Printable PDF Format

Field Guides Tour Report Australia Part 2 2019 Oct 22, 2019 to Nov 11, 2019 John Coons & Doug Gochfeld For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Water is a precious resource in the Australian deserts, so watering holes like this one near Georgetown are incredible places for concentrating wildlife. Two of our most bird diverse excursions were on our mornings in this region. Photo by guide Doug Gochfeld. Australia. A voyage to the land of Oz is guaranteed to be filled with novelty and wonder, regardless of whether we’ve been to the country previously. This was true for our group this year, with everyone coming away awed and excited by any number of a litany of great experiences, whether they had already been in the country for three weeks or were beginning their Aussie journey in Darwin. Given the far-flung locales we visit, this itinerary often provides the full spectrum of weather, and this year that was true to the extreme. The drought which had gripped much of Australia for months on end was still in full effect upon our arrival at Darwin in the steamy Top End, and Georgetown was equally hot, though about as dry as Darwin was humid. The warmth persisted along the Queensland coast in Cairns, while weather on the Atherton Tablelands and at Lamington National Park was mild and quite pleasant, a prelude to the pendulum swinging the other way. During our final hours below O’Reilly’s, a system came through bringing with it strong winds (and a brush fire warning that unfortunately turned out all too prescient). -

Tiger Snake Antivenom

Husbandry Manual for Tiger Snakes Notechis spp (Peters 1861) sl Reptilia:Elapidae Author: John. J. Mostyn Date of Preparation: 2006 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond Course Name and Number: Captive Animal Management 1068 Lecturer: Graeme Phipps / Andrew Titmuss/ Jacki Salkeld/ Elissa Smith © 2006 John J Mostyn 1 Occupational Health and Safety WARNING This Snake is DANGEROUSLY VENOMOUS CAPABLE OF INFLICTING A POTENTIALLY FATAL BITE ALWAYS HAVE A COMPRESSION BANDAGE WITHIN REACH FIRST AID FOR A SNAKE BITE 1) Apply a firm, broad, pressure bandage to bitten limb, and if possible, the whole length of limb, firmly. 2) The limb should be immobilized by a splint and kept as still as possible. 3) Keep the patient still and call for ambulance. Immobilization and the use of a pressure bandage reduces the movement of venom from the bite site. This restriction of venom will allow more time to transport the patient to hospital. The patient should remain calm and rest. If possible, transport should be brought to the patient, rather than patient to transport. Fig 1 (Mirtschin, Davis, 1992) 2 Tiger Snake Antivenom What is Tiger Snake Antivenom? Tiger snake antivenom is an injection designed to help neutralize the effect of the poison (venom) of the tiger snake. It is produced by immunizing horses against the venom of the tiger snake and then collecting that part of the horse’s blood which neutralizes this poison. The antivenom is purified and made into an injection for those people who may need it after being bitten by a tiger snake. Tiger snake antivenom is also the appropriate antivenom if you are bitten by a copperhead snake, a rough scaled snake or a member of the black snake family. -

Myths Surrounding Snakes

MYTHS SURROUNDING SNAKES MYTH 1: Bites from baby venomous snakes are more dangerous than those from adults because they always deliver a full dose of venom. The legend goes that young snakes have not yet learned how to control the amount of venom they inject. They are therefore more dangerous than adult snakes, which will restrict the amount of venom they use in a bite or “dry bite”. This is simply untrue and all the evidence points towards bites from adults being more severe. Tests have shown that juvenile snakes can control their venom just as much as adults. Furthermore lets consider the following factors: adults have significantly larger fangs to deliver their venom and considerably more venom available than a juvenile. Therefore if a juvenile has venom glands only big enough to hold a 2ml of venom compared to an adult that can hold 30ml or more, then the bite from an adult will always have the potential to be more severe. I presume the reason this myth came into existence was to dissuade people from having a carefree attitude towards the potential dangers of a juvenile snake. The moral of the story is to treat every snake as a potentially dangerous and never expose your self to a situation where a snake of any size can bite you. MYTH 2: If you see a snake they’ll always be more Although it is possible to see more than one snake, for the most part this statement is untrue. Snakes are solitary animals for most of their lives so generally you will only ever encounter individuals. -

Birdquest Australia (Western and Christmas

Chestnut-backed Button-quail in the north was a bonus, showing brilliantly for a long time – unheard of for this family (Andy Jensen) WESTERN AUSTRALIA 5/10 – 27 SEPTEMBER 2017 LEADER: ANDY JENSEN ASSISTANT: STUART PICKERING ! ! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Western Australia (including Christmas Island) 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com Western Shrike-tit was one of the many highlights in the southwest (Andy Jensen) Western Australia, if it were a country, would be the 10th largest in the world! The BirdQuest Western Australia (including Christmas Island) 2017 tour offered an unrivalled opportunity to cover a large portion of this area, as well as the offshore territory of Christmas Island (located closer to Indonesia than mainland Australia). Western Australia is a highly diverse region with a range of habitats. It has been shaped by the isolation caused by the surrounding deserts. This isolation has resulted in a richly diverse fauna, with a high degree of endemism. A must visit for any birder. This tour covered a wide range of the habitats Western Australia has to offer as is possible in three weeks, including the temperate Karri and Wandoo woodlands and mallee of the southwest, the coastal heathlands of the southcoast, dry scrub and extensive uncleared woodlands of the goldfields, coastal plains and mangroves around Broome, and the red-earth savannah habitats and tropical woodland of the Kimberley. The climate varied dramatically Conditions ranged from minus 1c in the Sterling Ranges where we were scraping ice off the windscreen, to nearly 40c in the Kimberley, where it was dust needing to be removed from the windscreen! We were fortunate with the weather – aside from a few minutes of drizzle as we staked out one of the skulkers in the Sterling Ranges, it remained dry the whole time. -

Tasmania 2018 Ian Merrill

Tasmania 2018 Ian Merrill Tasmania: 22nd January to 6th February Introduction: Where Separated from the Australian mainland by the 250km of water which forms the Bass Strait, Tasmania not only possesses a unique avifauna, but also a climate, landscape and character which are far removed from the remainder of the island continent. Once pre-trip research began, it was soon apparent that a full two weeks were required to do justice to this unique environment, and our oriGinal plans of incorporatinG a portion of south east Australia into our trip were abandoned. The following report summarises a two-week circuit of Tasmania, which was made with the aim of seeinG all island endemic and speciality bird species, but with a siGnificant focus on mammal watchinG and also enjoyinG the many outstandinG open spaces which this unique island destination has to offer. It is not written as a purely ornitholoGical report as I was accompanied by my larGely non-birdinG wife, Victoria, and as such the trip also took in numerous lonG hikes throuGh some stunninG landscapes, several siGhtseeinG forays and devoted ample time to samplinG the outstandinG food and drink for which the island is riGhtly famed. It is quite feasible to see all of Tasmania's endemic birds in just a couple of days, however it would be sacrilegious not to spend time savourinG some of the finest natural settinGs in the Antipodes, and enjoyinG what is arguably some of the most excitinG mammal watchinG on the planet. Our trip was huGely successful in achievinG the above Goals, recordinG all endemic birds, of which personal hiGhliGhts included Tasmanian Nativehen, Green Rosella, Tasmanian Boobook, four endemic honeyeaters and Forty-spotted Pardalote. -

A Comparison of Two Populations of Tiger Snakes, Notechis Scutatus Occidentalis

A Comparison of Two Populations of Tiger Snakes, Notechis scutatus occidentalis : The Influence of Phenotypic Plasticity on Various Life History Traits Fabien Aubret (DEA) Laboratoire d’Herpétologie, CEBC– CNRS, Université de Poitiers School of Animal Biology, University of Western Australia This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Western Australia and of the Université de Poitiers. March 2005 “Not a single one of your ancestors died young. They all copulated at least once. ” Richard Dawkins (b. 1941). 2 Summary The phenotype of any living organism reflects not only its genotype, but also direct effects of environmental conditions. Some manifestations of environmental effects may be non-adaptive, such as fluctuating asymmetry. Growing evidence nevertheless suggests that natural selection has fashioned norms of reaction such that organisms will tend to display developmental trajectories that maximise their fitness in the environment which they encounter via enhanced growth, survival, and/or reproduction. Over recent decades, the adaptive value of phenotypic plasticity has become a central theme in evolutionary biology. Plasticity may have evolutionary significance either by retarding evolution (by making selection on genetic variants less effective), or by enhancing evolution (as a precursor to adaptive genetic change). Reptiles are excellent models for the study of such theories, notably because they show high degrees of phenotypic plasticity. Many plastic responses have now been documented, using a diversity of taxa (turtles, crocodiles, snakes, lizards) and examining a number of different traits such as morphology, locomotor performance, and general behaviour. Islands are of special interest to ecologists and evolutionary biologists because of the rapid shifts possible in island taxa with small and discrete populations, living under conditions (and selective pressures) often very different from those experienced by their mainland conspecific. -

Download Full Text (Pdf)

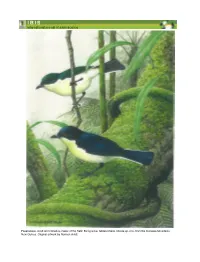

FRONTISPIECE. Adult and immature males of the Satin Berrypecker Melanocharis citreola sp. nov. from the Kumawa Mountains, New Guinea. Original artwork by Norman Arlott. Ibis (2021) doi: 10.1111/ibi.12981 A new, undescribed species of Melanocharis berrypecker from western New Guinea and the evolutionary history of the family Melanocharitidae BORJA MILA, *1 JADE BRUXAUX,2,3 GUILLERMO FRIIS,1 KATERINA SAM,4,5 HIDAYAT ASHARI6 & CHRISTOPHE THEBAUD 2 1National Museum of Natural Sciences, Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), Madrid, 28006, Spain 2Laboratoire Evolution et Diversite Biologique, UMR 5174 CNRS-IRD, Universite Paul Sabatier, Toulouse, France 3Department of Ecology and Environmental Science, UPSC, Umea University, Umea, Sweden 4Biology Centre of Czech Academy of Sciences, Institute of Entomology, Ceske Budejovice, Czech Republic 5Faculty of Sciences, University of South Bohemia, Ceske Budejovice, Czech Republic 6Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense, Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), Cibinong, Indonesia Western New Guinea remains one of the last biologically underexplored regions of the world, and much remains to be learned regarding the diversity and evolutionary history of its fauna and flora. During a recent ornithological expedition to the Kumawa Moun- tains in West Papua, we encountered an undescribed species of Melanocharis berrypecker (Melanocharitidae) in cloud forest at an elevation of 1200 m asl. Its main characteristics are iridescent blue-black upperparts, satin-white underparts washed lemon yellow, and white outer edges to the external rectrices. Initially thought to represent a close relative of the Mid-mountain Berrypecker Melanocharis longicauda based on elevation and plu- mage colour traits, a complete phylogenetic analysis of the genus based on full mitogen- omes and genome-wide nuclear data revealed that the new species, which we name Satin Berrypecker Melanocharis citreola sp. -

In the Tasmanian Native Hen (Gallinula Mortierii): Is It Caused By

528 ShortCommunications [Auk, Vol. 115 LITERATURE CITED strap Penguin(Pygoscelis antarctica) 1. Sexroles and effectson fitness.Polar Biology 15:533-540. BIRKHEAD,t. R., AND A. P. MOLLER.1992. Sperm SLADEN,W. J. L. 1958.The pygoscelidpenguins. II. competitionin birds: Causesand consequences. The Ad•lie Penguin.Falkland Islands Depen- Academic Press, London. denciesSurvey Scientific Reports 17:23-97. BROWN,R. G. B. 1967. Courtship behavior in the SPURR,E. B. 1975a. Communication in the Ad•lie Lesser Black-backedGull, Larusfuscus. Behav- Penguin.Pages 449-501 in The biology of pen- iour 29:122-153. guins (B. Stonehouse,Ed.). Macmillan,London. DERKSEN,D. V. 1975. Unreportedmethod of stone SPURR,E. B. 1975b.Breeding of the Ad•lie Penguin collectingby the Ad•lie Penguin. Notornis 22: Pygoscelisadeliae at Cape Bird. Ibis 117:324-338. 77-78. TASKER,C. R., AND J. g. MILLS. 1981. A functional HUNTER, E M., L. S. DAVIS, AND G. D. MILLER. 1996. analysisof courtshipfeeding in the Red-billed Sperm transfer in the Ad61iePenguin. Condor 98:410-413. Gull (Larus novaehollandiae).Behaviour 77:222- 241. HUNTER, E M., G. D. MILLER, AND L. S. DAVIS. 1995. Mate switchingand copulationbehaviour in the TAYLOR,R. I7I. 1962. The Ad•lie PenguinPygoscelis Ad61iePenguin. Behaviour 132:691-707. adeliaeat Cape Royds. Ibis 104:176-204. LACK,D. 1940. Courtship feeding in birds. Auk 57: WESTNEAT, D. E, P. W. SHERMAN, AND M. L. MORTON. 169-178. 1990. The ecology and evolution of extrapair MCKINNEY, E, K. M. CHENG, AND D. J. BRUGGERS. copulationsin birds. Current Ornithology 7: 1984.Sperm competition in apparentlymonog- 331-369. -

The Role of Adaptive Plasticity in a Major Evolutionary Transition

Functional Blackwell Publishing Ltd Ecology 2007 The role of adaptive plasticity in a major evolutionary 21, 1154–1161 transition: early aquatic experience affects locomotor performance of terrestrial snakes F. AUBRET,*† X. BONNET‡ and R. SHINE* *University of Sydney, Biological Sciences A08, 2006 New South Wales, Australia, ‡Centre d’Etudes Biologiques de Chizé, CNRS, 79360 Villiers en Bois, France Summary 1. Many phylogenetic lineages of animals have undergone major habitat transitions, stimulating dramatic phenotypic changes as adaptations to the novel environment. Although most such traits clearly reflect genetic modification, phenotypic plasticity may have been significant in the initial transition between habitat types. 2. Elapid snakes show multiple phylogenetic shifts from terrestrial to aquatic life. We raised young tigersnakes (a terrestrial taxon closely related to sea-snakes) in either a terrestrial or aquatic environment for a 5-month period. 3. The snakes raised in water were able to swim 26% faster, but crawled 36% more slowly, than did their terrestrially-raised siblings. A full stomach impaired locomotor performance, but snakes were less impaired when tested in the environment in which they had been raised. 4. Thus, adaptively plastic responses to local environments may have facilitated aquatic performance (and impaired terrestrial performance) in ancestral snakes as they shifted from terrestrial to aquatic existence. 5. Such plasticity may have influenced the rate or route of this evolutionary transition between habitats, and should be considered when comparing habitat-specific locomotor abilities of present-day aquatic and terrestrial species. key-words: development, elapid, locomotion, phenotype Functional Ecology (2007) 21, 1154–1161 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01310.x that vary over small spatial and temporal scales. -

Download the Bird List

Bird list for PAIWALLA WETLANDS -35.03468 °N 139.37202 °E 35°02’05” S 139°22’19” E 54 351500 6121900 or new birdssa.asn.au ……………. …………….. …………… …………….. … …......... ……… Observers: ………………………………………………………………….. Phone: (H) ……………………………… (M) ………………………………… ..………………………………………………………………………………. Email: …………..…………………………………………………… Date: ……..…………………………. Start Time: ……………………… End Time: ……………………… Codes (leave blank for Present) D = Dead H = Heard O = Overhead B = Breeding B1 = Mating B2 = Nest Building B3 = Nest with eggs B4 = Nest with chicks B5 = Dependent fledglings B6 = Bird on nest NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. Red-necked Avocet Black Falcon Spur-winged Plover (Masked Lapwing) Rainbow Bee-eater Brown Falcon Australasian Bittern Peregrine Falcon Australian Pratincole Black-backed Bittern Galah Brown Quail Eastern Bluebonnet Black-tailed Godwit Stubble Quail Australian Boobook Cape Barren Goose Buff-banded Rail Brush Bronzewing Brown Goshawk Lewin's Rail Common Bronzewing Australasian Grebe Mallee Ringneck (Australian Ringneck) Budgerigar Great Crested Grebe Cockatiel Hoary-headed Grebe Adelaide Rosella (Crimson Rosella) Sulphur-crested Cockatoo Common Greenshank Eurasian Coot Silver Gull Common Sandpiper Little Corella Hardhead Curlew Sandpiper Great Cormorant Spotted Harrier Marsh Sandpiper Little Black Cormorant Swamp Harrier Pectoral Sandpiper Little Pied Cormorant Nankeen Night Heron Sharp-tailed Sandpiper Pied Cormorant White-faced Heron Wood Sandpiper Australian Crake White-necked