The Legends of the Jews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download 1St Season of Game of Thrones Free Game of Thrones, Season 1

download 1st season of game of thrones free Game of Thrones, Season 1. Game of Thrones is an American fantasy drama television series created for HBO by David Benioff and D. B. Weiss. It is an adaptation of A Song of Ice and Fire, George R. R. Martin's series of fantasy novels, the first of which is titled A Game of Thrones. The series, set on the fictional continents of Westeros and Essos at the end of a decade-long summer, interweaves several plot lines. The first follows the members of several noble houses in a civil war for the Iron Throne of the Seven Kingdoms; the second covers the rising threat of the impending winter and the mythical creatures of the North; the third chronicles the attempts of the exiled last scion of the realm's deposed dynasty to reclaim the throne. Through its morally ambiguous characters, the series explores the issues of social hierarchy, religion, loyalty, corruption, sexuality, civil war, crime, and punishment. The PlayOn Blog. Record All 8 Seasons Game of Thrones | List of Game of Thrones Episodes And Running Times. Here at PlayOn, we thought. wouldn't it be great if we made it easy for you to download the Game of Thrones series to your iPad, tablet, or computer so you can do a whole lot of binge watching? With the PlayOn Cloud streaming DVR app on your phone or tablet and the Game of Thrones Recording Credits Pack , you'll be able to do just that, AND you can do it offline. That's right, offline . -

“Big on Family”: the Representation of Freaks in Contemporary American Culture

Master’s Degree programme – Second Cycle (D.M. 270/2004) in History of North-American Culture Final Thesis “Big on Family”: The Representation of Freaks in Contemporary American Culture Supervisor Ch. Prof. Simone Francescato Ch. Prof. Fiorenzo Iuliano University of Cagliari Graduand Luigi Tella Matriculation Number 846682 Academic Year 2014 / 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF ILLUSTRATIONS ............................................................................................. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ....................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER I: FREAKS IN AMERICA .............................................................................. 11 1.1 – The Notion of “Freak” and the Freak Show ........................................................... 11 1.1.1 – From the Monstrous Races to Bartholomew Fair ................................................. 14 1.1.2 – Freak Shows in the United States ......................................................................... 20 1.1.3 – The Exotic Mode and the Aggrandized Mode ...................................................... 28 1.2 – The Representation of Freaks in American Culture ............................................. 36 1.2.1 – Freaks in American Literature .............................................................................. 36 1.2.2 – Freaks on Screen .................................................................................................. -

Love Enthroned

Love Enthroned Author(s): Steele, Daniel (1824-1914) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Daniel Steele firmly agreed with John Wesley that Christians can and should live a life free of voluntary sin. This striving towards perfection of faith became known as the ªHoliness Movement.º Originally a Methodist/Wesleyan phenomenon, the movement came to have profound effects on later Pentecostal and evangelical Christian communities. This work lays out the doctrine of sanctification, and urges readers to seek further sanctification in everyday life. Because Steele shares his own personal testimony of his faith, the book takes on a decidedly more intimate and relatable nature. Kathleen O'Bannon CCEL Staff Subjects: Doctrinal theology Salvation i Contents Title Page 1 Chapter 1. Love Revealed. 2 Chapter 2. Love Militant. 5 Chapter 3. Love Triumphant Over Original Sin 11 Chapter 4. Full Salvation Immediately Attainable 14 Chapter 5. Bible Texts For Sin Examined 20 Chapter 6. Deliverance Deferred 24 Chapter 7. Metaphorical Representations of Perfect Love 28 Chapter 8. St. Paul's Great Prayer of the Higher Life 40 Chapter 9. The Three Dispensations 47 Chapter 10. Perfect Love as a Definite Blessing 54 Chapter 11. The Fruits of Perfect Love 57 Chapter 12. Salvation From Artificial Appetites 67 Chapter 13. The Full Assurance of Faith 72 Chapter 14. The Evidences of Perfect Love 88 Chapter 15. Testimony 95 Chapter 16. Spiritual Dynamics 109 Chapter 17. Stumbling-Blocks in the King's Highway 114 Chapter 18. Growth in Grace 119 Chapter 19. Objections Answered. 122 Chapter 20. An Address to the Young Convert--the Higher Path 127 Chapter 21. -

Final Draft Thesis Corrected

REDEFINING MASCULINITY IN GAME OF THRONES !1 Redefining Masculinity through Disability in HBO’s Game of Thrones A Capstone Thesis Submitted to Southern Utah University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Professional Communication April 2016 By Amanda J. Dearman Capstone Committee: Dr. Kevin A. Stein, Ph.D., Chair Dr. Arthur Challis, Ed.D. Dr. Matthew H. Barton, Ph.D. Running head: REDEFINING MASCULINITY IN GAME OF THRONES !3 Acknowledgements I have been blessed with the support of a number of number of people, all of whom I wish to extend my gratitude. The completion of my Master’s degree is an important milestone in my academic career, and I could not have finished this process without the encouragement and faith of those I looked toward for support. Dr. Kevin Stein, I can’t thank you enough for your commitment as not only my thesis chair, but as a professor and colleague who inspired many of my creative endeavors. Under your guidance I discovered my love for popular culture studies and, as a result, my voice in critical scholarship. Dr. Art Challis and Dr. Matthew Barton, thank you both for lending your insight and time to my committee. I greatly appreciate your guidance in both the completion of my Master’s degree and the start of my future academic career. Your support has been invaluable. Thank you. To my family and friends, thank you for your endless love and encouragement. Whether it was reading my drafts or listening to me endlessly ramble on about my theories, your dedication and participation in this accomplishment is equal to that of my own. -

Comparing Depictions of Empowered Women Between a Game of Thrones Novel and Television Series

Journal of Student Research (2012) Volume 1, Issue 3: pp. 14-21 Research Article A Game of Genders: Comparing Depictions of Empowered Women between A Game of Thrones Novel and Television Series Rebecca Jonesa The main women in George R. R. Martin's novel Game of Thrones, first published in 1996, and the adapted television series in 2011, are empowered female figures in a world dominated by male characters. Analyzing shifts in the characters’ portrayals between the two media conveys certain standards of the cultures for which they are intended. While in the novel the characters adhere to a different set of standards for women, the television series portrays these women as more sympathetic, empowered, and realistic with respect to contemporary standards. Using literary archetypes of queen, hero, mother, child, maiden and warrior and applying them to Cersei Lannister, Catelyn Stark, Arya Stark, Sansa Stark, and Daenerys Targeryen, provides a measure for the differences in their presentations. Through the archetypical lens, the shifts in societal and cultural standards between the novel and series’ airing make apparent the changing pressures and expectations for women. By reading the novel and watching the series with these archetypes in mind, the changes in gender norms from 1996 to 2011 become clear. The resulting shift shows the story’s advances in the realm of fantasy in relation to the American society that consumes it. Keywords: English, Film Studies, Women and Gender Studies 1. Introduction The genre of fantasy has a long and sordid history in its differences in portrayal between the two media, utilizing the depictions of women. -

Carolyne Larrington

Winter is coming Carolyne Larrington Winter is coming LES RACINES MÉDIÉVALES DE GAME OF THRONES Traduit de l’anglais par Antoine Bourguilleau ISBN 978‑2‑3793‑3049‑0 Dépôt légal – 1re édition : 2019, avril © Passés Composés / Humensis, 2019 170 bis, boulevard du Montparnasse, 75014 Paris Le code de la propriété intellectuelle n’autorise que « les copies ou reproductions stric‑ tement réservées à l’usage privé du copiste et non destinées à une utilisation collec‑ tive » [article L. 122‑5] ; il autorise également les courtes citations effectuées dans un but d’exemple ou d’illustration. En revanche « toute représentation ou reproduction intégrale ou partielle, sans le consentement de l’auteur ou de ses ayants droit ou ayants cause, est illicite » [article L. 122‑4]. La loi 95‑4 du 3 janvier 1994 a confié au C.F.C. (Centre français de l’exploitation du droit de copie, 20, rue des Grands Augustins, 75006 Paris), l’exclusivité de la gestion du droit de reprographie. Toute photocopie d’oeuvres protégées, exécutée sans son accord préalable, constitue une contrefaçon sanctionnée par les articles 425 et suivants du Code pénal. Sommaire Liste des abréviations ....................................................... 9 Préface ................................................................................ 15 Introduction ....................................................................... 19 Chapitre 1. Le Centre ........................................................ 31 Chapitre 2. Le Nord ......................................................... -

Game of Thrones“

Hochschule der Medien Bachelorarbeit im Studiengang Audiovisuelle Medien (AMB) The Sound of Ice and Fire Eine Sounddesignanalyse der Serie „Game of Thrones“ Vorgelegt von Sabrina Kreuzer Matrikelnummer 23978 am 31. Juli 2015 Erstprüfer: Prof. Oliver Curdt Zweitprüfer: Prof. Jörn Precht Eidesstattliche Erklärung Hiermit versichere ich, Sabrina Kreuzer, an Eides Statt, dass ich die vorliegende Bachelorar- beit mit dem Titel The Sound of Ice and Fire – Eine Sounddesignanalyse der Serie „Game of Thrones” selbständig und ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebenen Hilfsmit- tel benutzt habe. Die Stellen der Arbeit, die dem Wortlaut oder dem Sinn nach anderen Werken entnommen wurden, sind in jedem Fall unter Angabe der Quelle kenntlich gemacht. Die Arbeit ist noch nicht veröffentlicht oder in anderer Form als Prüfungsleistung vorgelegt worden. Ich habe die Bedeutung der eidesstattlichen Versicherung und die prüfungsrechtlichen Fol- gen (§26 Abs. 2 Bachelor-SPO (6 Semester), § 23 Abs. 2 Bachelor-SPO (7 Semester) bzw. § 19 Abs. 2 Master-SPO der HdM) sowie die strafrechtlichen Folgen (gem. § 156 StGB) einer un- richtigen oder unvollständigen eidesstattlichen Versicherung zur Kenntnis genommen. Stuttgart, den 31. Juli 2015 Kurzfassung Diese Arbeit befasst sich mit dem Sounddesign der Serie „Game of Thrones“. Die Analyse des Sounddesigns soll dazu führen, die zentralen Fragestellungen 1) Welche Rolle spielen Sprache und Dialoge in „Game of Thrones“? 2) Welche Funktionen haben die Geräusche? beantworten zu können. Im ersten Kapitel wird eine allgemeine Übersicht der Serie gegeben. Das zweite Kapitel be- schäftigt sich mit den Themen Sprache und Dialoge, Geräusche und akustische Eigenschaften der Handlungsorte. Im dritten Kapitel werden abschließende Bemerkungen formuliert. -

A Dance with Deviants: the Sexual As Fantastic in a Song of Ice and Fire

A Dance with Deviants: The Sexual as Fantastic in A Song of Ice and Fire by Lars Johnson A thesis presented for the B.S. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2019 © 2019 Lars Johnson For Hannah, who has accompanied me on our journey through Westeros Acknowledgments J.R.R. Tolkien said that The Lord of the Rings was a tale that grew in the telling. I would have to echo Tolkien’s sentiment with regards to this thesis and thus have a great many people to thank for its growth and eventual completion. First, I extend my sincerest, most heartfelt thanks to my intrepid advisor Lisa Makman. I certainly could not have succeeded without her surefooted guidance through the mountainous expanses of fantasy theory (and every other form of theory I encountered as I wrote, for that matter). Dr. Makman was commendably tolerant of my 4:00 AM emails and always knew just what direction to steer me in when I came to her with my grotesquely jumbled piles of notes and collections of ideas. I truly could not have asked for a more fantastic(al) mentor. I also must express profound gratitude to Sean Silver, whose extensive knowledge of digital methods saw me through the trials of coding. Though he was on the other side of the globe as I prepared this thesis, Dr. Silver was never more than an email away and always offered superb counsel. Adela Pinch, Honors director and wealth of literary and rhetorical knowledge, was also a massive aid in the shaping of this thesis. -

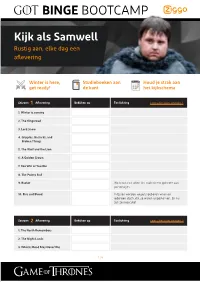

Binge Bootcamp

BINGE BOOTCAMP Kijk als Samwell Rustig aan, elke dag een aflevering Winter is here, Studieboeken aan Houd je strak aan get ready! de kant het kijkschema Seizoen1 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 1 1. Winter is coming 2. The Kingsroad 3. Lord Snow 4. Cripples, Bastards, and Broken Things 5. The Wolf and the Lion 6. A Golden Crown 7. You Win or You Die 8. The Pointy End 9. Baelor We leren een wijze les: raak niet te gehecht aan personages. 10. Fire and Blood In Essos worden wezens geboren waarvan iedereen dacht dat ze waren uitgestorven. En nu zijn ze nog cute! Seizoen2 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 2 1. The North Remembers 2. The Night Lands 3. What is Dead May Never Die 1 /4 BINGE BOOTCAMP Seizoen2 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 2 4. Garden of Bones 5. The Ghost of Harranhal 6. The Old Gods and the New 7. A Man Without Honor 8. The Prince of Winterfell 9. Blackwater King’s Landing, de hoofdstad van de Seven Kingsdoms, wordt aangevallen. Wat volgt is episch. 10. Valar Morghulis Seizoen3 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 3 1. Valar Dohaeris 2. Dark Wings, Dark Words 3. Walk of Punishment 4. And Now His Watch is 5. Kissed by Fire 6. The Climb 7. The Bear and the Maiden 8. Second Sons 9. The Rains of Castamere 10. Mhysa Seizoen4 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 4 1. Two Swords 2. The Lion and the Rose Wraak is zoet! 3. -

Mastering the Game of Thrones This Page Intentionally Left Blank Mastering the Game of Thrones Essays on George R.R

Mastering the Game of Thrones This page intentionally left blank Mastering the Game of Thrones Essays on George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire Edited by Jes Battis and Susan Johnston McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina Also of Interest Blood Relations: Chosen Families in Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel, by Jes Battis (McFarland, 2005) Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Mastering the Game of thrones : essays on George R.R. Martin’s A song of ice and fire / edited by Jes Battis and Susan Johnston . p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-9631-0 (softcover : acid free paper) ISBN 978-1-4766-1962-0 (ebook) ♾ 1. Martin, George R. R. Song of ice and f ire. I. Battis, Jes, 1979– editor. II. Johnston, Susan, 1964– editor. III. Game of thrones (Television program) PS3563.A7239S5935 2015 813'.54—dc23 2014044427 British Library cataloguing data are available © 2015 Jes Battis and Susan Johnston. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover images © 2015 iStock/Thinkstock Printed in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com For my mother, who watches from beneath her wolf blanket.—Jes For Marcel, shekh ma shieraki anni.—Susan Acknowledgments As the first of its kind, this volume was a challenging if rewarding endeavor. -

King Joffrey Playing the Game. Serielles Erzählen Und Mediale Inszenierungen Von Macht Und Herrschaft in Der HBO-Erfolgsserie Game of Thrones (2011–2019)

Anna Isabell Wörsdörfer (Gießen) King Joffrey playing the game. Serielles Erzählen und mediale Inszenierungen von Macht und Herrschaft in der HBO-Erfolgsserie Game of Thrones (2011–2019) „When you play the game of thrones you win or you die.“1 Als High-End-TV-Drama sprengt die HBO-Serie Game of Thrones mit nunmehr sechs (von acht) veröffentlichten Staffeln nicht nur regelmäßig Zuschauerrekorde, sondern ist auch als progressives Serial-Format unter dem Aspekt der seriellen Narration richtungsweisend. Ihre komplexe Handlungsstruktur verdankt die Produktion des US- Pay-TV-Senders der Verortung in einem mittelalterlich anmutenden, von Konflikten dominierten Fantasy-Universum mit mehreren ‚Brennpunkten‘ und einem entsprechend umfangreichen Charakterinventar: Die Serienwelt ist insbesondere in ihrem kulturellen Zentrum, dem Kontinent Westeros und den auf diesem beheimateten Sieben Königslanden, ein ritterlich geprägter Raum basierend auf dynastischen Beziehungen und vasallischen Abhängigkeiten, welcher in seinen politischen und sozialen Grundstrukturen stark an das europäische Mittelalter resp. einen höfischen Eklektizismus erinnert.2 Ebenso wie ihre literarische Vorlage, George R. R. Martins Fantasy-Saga A Song of Ice and Fire (seit 1996), präsentiert die Serie, die mittlerweile ebenfalls die medien-, kultur- und literaturwissenschaftliche Forschung in ihren Bann zieht,3 in einem ihrer 1 Cersey Lannister zu Eddard Stark in der Folge „You Win or You Die“ (S1.07, [9:00]). 2 Die Peripherien sind hingegen eher als archaisch zu bezeichnen, wie etwa der benachbarte Kontinent Essos, der deutliche Parallelen zur antiken Welt (z. B. Harpyien-Mythologie, Sklaventum, Gladiatorenkämpfe) aufweist. 3 Exemplarisch seien hier der jüngst erschienene erste Sammelband (Jes Battis (Hg.): Mastering the Game of Thrones. Essays on George R.R. -

A Psychoanalytical Study on Arya Stark's Development In

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI A PSYCHOANALYTICAL STUDY ON ARYA STARK’S DEVELOPMENT IN GAME OF THRONES AN UNDER GRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By REBECCA THALIA CARISSA HALIM Student Number: 154214035 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2020 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI A PSYCHOANALYTICAL STUDY ON ARYA STARK’S DEVELOPMENT IN GAME OF THRONES AN UNDER GRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By REBECCA THALIA CARISSA HALIM Student Number: 154214035 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2020 ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI "The world doesn't just let girls decide what they want to be. But I can now." (Arya Stark) vii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI For mami viii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This part is especially made to express my gratitude for those who have helped and supported me during my thesis writing. I owe my deepest appreciation to my thesis advisor Sri Mulyani, Ph.D. for she has always been very supportive, to my co-advisor Dr. Gabriel Fajar Sasmita Aji M. Hum. for he has given me corrections and suggestions, to Mbak Ninik for she has always been so helpful and lastly to all of the lecturers of Universitas Sanata Dharma, thankyou for the education, thankyou for the time.