David Finckel, Cello Wu Han, Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2Majors and Minors.Qxd.KA

As printed January 2005 MUSIC Music (MUS, JAZ) Major and Minors in Music Department of Music, College of Arts and Sciences CHAIRPERSON: Judith Lochhead DIRECTOR OF UNDERGRADUATE STUDIES: Perry Goldstein UNDERGRADUATE SECRETARY: Germaine Berry OFFICE: 3304 Staller Center for the Arts PHONE: (631) 632-7330 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEB ADDRESS: www.sunysb.edu/music Minors of particular interest to students majoring in Music: Anthropology (ANT), Art History (ARH), Cinema and Cultural Studies (CCS), Dance (DAN), English (EGL), History (HIS), Philosophy (PHI), Theatre Arts (THR) Faculty Joyce Robbins, Professor Emerita, B.S., Michael Powell, Artist in Residence, B. Mus., Ray Anderson, Visiting Professor, Director of Juilliard School of Music: Violin; viola; peda- Wichita State: Trombone. Jazz Program and Stony Brook Jazz Band, gogy; chamber music. William Purvis, Artist in Residence, B.A., Empire State College: Jazz studies; jazz impro- Daria Semegen, Associate Professor and Haverford College: Horn; chamber music. visation. Director of Electronic Music Studio, M.Mus., Philip Setzer, Artist in Residence, M.M., Joseph Auner, Professor, Ph.D., University of Yale University: Composition; theory; electronic Juilliard School of Music: Violin; chamber Chicago: 19th- and 20th-century history and music. music. theory. Sheila Silver, Professor, Ph.D., Brandeis Stephen Taylor, Artist in Residence, Diploma, Colin Carr, Professor, Certificate of University: Composition; theory. Juilliard School of Music: Oboe; chamber Performance, 1974, Yehudi Menuhin School: Jane Sugarman, Associate Professor, Ph.D., music. Cello; chamber music. University of California, Los Angeles: Chris Pedro Trakas, Artist in Residence, Joseph Carver, Assistant Professor, D.M.A., Ethnomusicology; world music cultures, south- M.Mus., University of Houston: Voice. -

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center New World Spirit Sunday, October 13, 2019 3:00 Pm Photo: Tristan Cook Tristan Photo

The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center New World Spirit Sunday, October 13, 2019 3:00 pm Photo: Tristan Cook Tristan Photo: 2019/2020 SEASON The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center GLORIA CHIEN, Piano NICHOLAS CANELLAKIS, Cello CHAD HOOPES, Violin DAVID FINCKEL, Cello KRISTIN LEE, Violin ANTHONY MANZO, Double Bass ARNAUD SUSSMANN, Violin RANSOM WILSON, Flute ANGELO XIANG YU, Violin DAVID SHIFRIN, Clarinet MATTHEW LIPMAN, Viola MARC GOLDBERG, Bassoon PAUL NEUBAUER, Viola Sunday, October 13, 2019, at 3:00 pm Hancher Auditorium, The University of Iowa PROGRAM New World Spirit This concert celebrates the intrepid American spirit by featuring two pairs of composers that shaped the course of American music. Harry T. Burleigh was a star student of Dvorákˇ at the National Conservatory in New York. A talented composer and singer, he exposed the Czech composer to American spirituals and was in turn encouraged by Dvorákˇ to perform his native African American folk music. Two generations later, Copland and Bernstein conceived a clean, clear American sound that conveys the wonder and awe of open spaces and endless possibilities. Southland Sketches for violin and piano (1916) Henry T. Burleigh I. Andante (1866–1949) II. Adagio ma non troppo III. Allegretto grazioso IV. Allegro Chad Hoopes and Gloria Chien Quintet in E-flat Major for two violins, two violas, Antonín Dvorákˇ and cello, Op. 97, (“American”) (1893) (1841–1904) I. Allegro non tanto II. Allegro vivo III. Larghetto IV. Finale: Allegro giusto Arnaud Sussmann, Angelo Xiang Yu, Paul Neubauer, Matthew Lipman, and Nicholas Canellakis INTERMISSION Sonata for Clarinet and Piano (1941–42) Leonard Bernstein I. -

Outpouring of Chamber Music in Seoul

Outpouring of chamber music in Seoul (The Emerson String Quartet, with pianist Wu Han, center, give an impassioned performance of a piano quintet by Dvorak at the IBK Chamber Hall, the latest addition to the Seoul Arts Center, Monday.) World’s top ensembles perform at new IBK Chamber Hall By Do Je-Hae A three-day chamber music festival featuring some of the world’s top musicians in the field wrapped up Tuesday, concluding the “IBK Chamber Hall Opening Festival” that started in October. The new IBK Chamber Hall at Seoul Arts Center is generating excitement for fans and artists who have longed for the ultimate live chamber music experience in the nation’s capital. It is also playing a vital role in Korea’s burgeoning chamber music scene. The 600-seat IBK Chamber Hall had a full house during the rare opportunity to hear the Emerson String Quartet and the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center(CMS) live consecutively in one week. The two groups as part of “Chamber Music Today” presented an extraordinary broad repertoire, ranging from Schubert’s gorgeous B-flat major piano trio to the evocative string quartet by French composer Maurice Ravel. The inaugural concert of “Chamber Music Today,” founded by cellist David Finckel and pianist Wu Han, began Sunday with a program of quartets by Mozart, Beethoven and Dvorak. “Chamber music is unlike any artistic medium - both powerful and personal, it has inspired countless composers to create some of their finest work,” Finckel said in a statement. “‘Chamber Music Today’ brings the greatest chamber music repertoire and performers to Korea. -

Artist Series: David Shifrin Program Notes on the Program

ARTIST SERIES: DAVID SHIFRIN PROGRAM WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791) Quintet in A major for Clarinet, Two Violins, Viola, and Cello, K. 581 (1789) Allegro Larghetto Menuetto Allegretto con variazioni David Shifrin, clarinet • Danbi Um, violin • Bella Hristova, violin • Mark Holloway, viola • Dmitri Atapine, cello LUIGI BASSI (1833-1871) Concert Fantasia on Themes from Verdi’s Rigoletto for Clarinet and Piano David Shifrin, clarinet • Gloria Chien, piano DUKE ELLINGTON (1899-1974) Clarinet Lament for Clarinet and Piano (1936) (arr. David Schiff) David Shifrin, clarinet • Gloria Chien, piano NOTES ON THE PROGRAM Quintet in A major for Clarinet, Two Violins, Viola, and Cello, K. 581 (1789) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Salzburg, 1756 – Vienna, 1791) Mozart wrote this quintet for Vienna’s Society of Musicians (Tonkünstler-Societät) in 1789. The society raised money to provide pensions to widows and orphans of Viennese musicians. Its concerts were regular occurrences on the Viennese social calendar and Mozart composed and performed for them, even though he was not a member, something he would regret right before his death at the age of 35. This quintet premiered at a society concert on December 22, 1789, in between two halves of a cantata by Vincenzo Righini. The clarinetist was Anton Stadler, one of the first virtuosos on the instrument and Mozart’s close personal friend. Mozart wrote all of his major clarinet works— this one, the Kegelstatt Trio, and the Clarinet Concerto—with Stadler’s playing in mind. Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center The clarinet was a relatively new instrument in Mozart’s day yet he expertly tapped into the instrument’s unique singing quality. -

David Shifrin: Practice Makes Perfect for Music@Menlo

July 8, 2011 David Shifrin: Practice Makes Perfect for Music@Menlo •Find classical, jazz and byoth Marianneer great Lipanovich• Learn about exciting family concerts concerts in your area • Read weekly news on young musicians • Enjoy lively feature articles on concerts and musicians It’s taken some time, but this year Music@Menlo finally, and happily, can add clarinetist David Shifrin to• its S e alistrch of fo rguest music artists. teache rThes an daward-winning music musician is equally happy to be pappearing.rograms in yNotour aonlyrea does he love chamber music, calling it his favorite, he also adores Brahms. So it’s a match made in heaven. THE BAY AREA’S GO-TO PLACE FOR GREAT MUSIC There’s no doubt that Shifrin’s resume is impressive, even for Music@ Menlo artists. He’s one of only two wind players to win the Avery Fisher Prize, in addition to other honors. In addition to guest appearances as a soloist and with ensembles, he’s a member of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center and a director of Chamber Music Northwest. And he’s on the faculty of the Yale School of Music, having previously served on the faculties of institutions such as Juilliard and the University of Hawaii. Brahms fans, take note: Along with Wu Han and David Finckel, earlier this year Shifrin recorded the same Brahms Trios that he’ll play in Menlo Park. The recording isn’t yet released, but attendees at the Carte Blanche concert on Aug. 8 will be able to purchase the CD. -

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Through Brahms the ninth season July 22–August 13, 2011 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 Through Brahms Program Overview 6 Essay: “Johannes Brahms: The Great Romantic” by Calum MacDonald 8 Encounters I–IV 11 Concert Programs I–VI 30 String Quartet Programs 37 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 50 Chamber Music Institute 52 Prelude Performances 61 Koret Young Performers Concerts 64 Café Conversations 65 Master Classes 66 Open House 67 2011 Visual Artist: John Morra 68 Listening Room 69 Music@Menlo LIVE 70 2011–2012 Winter Series 72 Artist and Faculty Biographies 85 Internship Program 86 Glossary 88 Join Music@Menlo 92 Acknowledgments 95 Ticket and Performance Information 96 Calendar Cover artwork: Mertz No. 12, 2009, by John Morra. Inside (p. 67): Paintings by John Morra. Photograph of Johannes Brahms in his studio (p. 1): © The Art Archive/Museum der Stadt Wien/ Alfredo Dagli Orti. Photograph of the grave of Johannes Brahms in the Zentralfriedhof (central cemetery), Vienna, Austria (p. 5): © Chris Stock/Lebrecht Music and Arts. Photograph of Brahms (p. 7): Courtesy of Eugene Drucker in memory of Ernest Drucker. Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 69) and Ani Kavafian (p. 75): Christian Steiner. Paul Appleby (p. 72): Ken Howard. Carey Bell (p. 73): Steve Savage. Sasha Cooke (p. 74): Nick Granito. -

DF Micro Bio 2019-2020

DAVID FINCKEL 2019-20 Season Micro Biography (295 words) Cellist David Finckel’s multifaceted career as concert performer, artistic director, recording artist, educator, and cultural entrepreneur distinguishes him as one of today’s most influential classical musicians. He is a recipient of Musical America’s Musician of the Year award. David Finckel appears annually at the world’s most prestigious concert series and venues, as both soloist and chamber musician. He tours extensively with pianist Wu Han and in trios with Philip Setzer. Together with Wu Han, David serves as Co-Artistic Director of The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center (CMS). Under his artistic leadership, CMS is celebrating three global broadcasting initiatives bringing chamber music to new audiences around the world, via partnerships with Medici TV, Radio Television Hong Kong and the All Arts broadcast channel. He is also Co-Artistic Director of Music@Menlo, the San Francisco Bay Area’s premier summer chamber music festival and institute. In the Far East, David Finckel serves as founding Co-Artistic Director of Chamber Music Today, a festival in Seoul, South Korea. David Finckel’s wide- ranging musical activities include the launch of ArtistLed, classical music’s first musician-directed and Internet-based recording company. BBC Music Magazine recently saluted the label’s twentieth anniversary with a special cover CD featuring David and Wu Han. Through a variety of educational initiatives, David has received universal praise for his passionate commitment to nurturing the artistic growth of countless young artists. Under the auspices of CMS, he led the LG Chamber Music School from 2009-2018, which served dozens of young musicians in South Korea annually. -

Emerson String Quartet

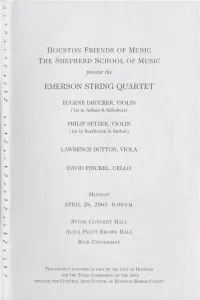

HOUSTON FRIENDS OF MUSIC THE SHEPHERD SCHOOL OF MUSIC present the EMERSON STRING QUARTET EUGENE DRUCKER, VIOLIN (1st in Aitken & Schubert) PHILIP SETZER, VIOLIN (1st in Beethoven & Barber) .. LAWRENCE DUTTON, VIOLA DAVID FINCKEL, CELLO MONDAY -,. APRIL 28, 2003 8:00 P.M. STUDE CONCERT HALL ALICE PRATT BROWN HALL RICE UNIVERSITY THIS PROJECT IS FUNDED IN PART BY THE CITY OF HOUSTON AND TIIE T EXAS COMMISSION ON THE ARTS THROUGH THE CULTURAL ARTS COUNCIL OF HOUSTON/HARRIS COUNTY. EMERSON STRING QUARTET -PROGRAM- LUDWIG van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827) Quartet in F Major, Op. 18, No. 1 (1798) Allegro con brio Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato Scherzo: Allegro molto Allegro HUGH AITKEN (b.1924) Laura Goes to India (1998) SAMUEL BARBER (1910-1981) A . Adagio for String Quartet, Op. 11 (1936) -INTERMISSION- FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) Quartet in D Minor, D. 810, "Death and the Maiden" (1824) Allegro Andante con moto Scherzo: Allegro molto Presto -.. The Emerson String Quartet appears by arrangement with IMC Artists and records exclusively for Deutsche Grammophon. www.emersonquartet.com LUDWIG van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827) Quartet in F Major, Op. 18, No. 1 (1798) ·.1 Beethoven wrote the Opus 18 Quartets during his first years in Vienna. He had arrived from Germany in 1792 by permission of the Elector of Bonn, shortly before his twenty-second birthday, in high spirits and carrying with him introductions to some of the most prominent members of music-loving Viennese nobility, who welcomed him into their substantial musical lives. At the end of his first four years in Vienna he had established himself as a pianist of major importance and a composer of the utmost promise; he had published, among other things, a set of three Piano Trios, Op.l, three Trios for Strings, Op. -

Wu Han, Philip Setzer, & David Finckel Trio

Wu Han, Philip Setzer, & David Finckel Trio Wu Han: Pianist Wu Han ranks among the most esteemed and influential classical musicians in the world today. Leading an unusually multifaceted artistic career, she has risen to international prominence through her wide-ranging activities as a concert performer, artistic director, recording artist, educator, and cultural entrepreneur. In recognition of artistic excellence and achievement in the arts, Wu Han and her longtime recital partner, cellist David Finckel, are recipients of Musical America’s Musicians of the Year award, one of the highest honors granted by the music industry. In high demand as a recitalist, concerto soloist, and chamber musician, Wu Han annually performs at the most prestigious concert venues and series across the world in recital with David Finckel, in piano trios with violinist Philip Setzer, and in piano quartets with violinist Daniel Hope and violist Paul Neubauer. Her most recent concerto appearances were with the Aspen Chamber Orchestra, the Atlanta Symphony, and the Philadelphia Orchestra. Highlights of her 2018–19 season include international and domestic tours as a duo with David Finckel and collaborations with a stellar lineup of artists and ensembles. She continues to perform with The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center (CMS) in New York and on tour; reunites with violinist Daniel Hope and violist Paul Neubauer for a U.S. tour reaching seven cities; and embarks on a series of piano trio performances in Canada and the United States with violinist Philip Setzer. As the winter unfolds, she joins CMS artists on tour to the Far East with appearances in Taipei and Hsinchu, Taiwan and Shanghai, China. -

David Finckel, Cello Wu Han, Piano

Sunday, January 20, 2019, 3pm Hertz Hall David Finckel, cello Wu Han, piano Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770–1827) Sonata No. 3 in A Major for Cello and Piano, Op. 69 (1807–08) Allegro ma non tanto Scherzo: Allegro molto Adagio cantabile – Allegro vivace Johannes BRAHMS (1833–1897) Sonata No. 1 in E minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 38 (1862–65) Allegro non troppo Allegretto quasi Menuetto Allegro INTERMISSION Felix MENDELSSOHN (1809–1847) Sonata No. 2 in D Major for Cello and Piano, Op. 58 (1843) Allegro assai vivace Allegretto scherzando Adagio Molto allegro e vivace David Finckel and Wu Han recordings are available exclusively through ArtistLed (www.artistled.com). Artist website: www.davidfinckelandwuhan.com Wu Han performs on the Steinway Piano. Cal Performances’ 2018 –19 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. Opposite: Photo by Lisa-Marie Mazzucco. PROGRAM NOTES German Mastery fered the composer a guaranteed annual Together, Ludwig van Beethoven, Johannes stipend to remain in Vienna. It is thought that Brahms, and Felix Mendelssohn represent the the dedication of the sonata was a gesture of peak of mastery in the German Classical and thanks to Gleichenstein. Aer the agreement Romantic traditions, and each composer wrote was signed, Beethoven asked Gleichenstein to significant works for cello and piano duo in help him find a wife. their respective pinnacle years. e sonatas A year aer the work was completed, Bee - featured in this program, as selected by David thoven complained that the sonata “had not yet Finckel and Wu Han, represent some of the been well performed in public.” e first record most important, celebrated, and masterfully of a performance is from 1812, when the work craed pieces in the duo repertoire. -

DFWH Duo Bio 19-20

DAVID FINCKEL & WU HAN 2019–20 Program biography (436 words) David Finckel and Wu Han are among the most esteemed and inFluential classical musicians in the world today. They are recipients oF Musical America’s Musicians of the Year award, one of the highest honors granted by the music industry. The energy, imagination, and integrity they bring to their multifaceted endeavors as concert perFormers, artistic directors, recording artists, educators, and cultural entrepreneurs go unmatched. Highlights oF their 2019–20 season include a new CD release, a national PBS television special, a new residency appointment, a busy international tour schedule, along with multiple perFormances with The Chamber Music Society oF Lincoln Center (CMS) in the United States, Taiwan and Columbia. David Finckel and Wu Han are currently in their third term as Artistic Directors oF The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Under their leadership, CMS is celebrating three global broadcasting initiatives bringing chamber music to new audiences around the world, via partnerships with Medici TV, Radio Television Hong Kong and the All Arts broadcast channel. David and Wu Han are the founders and Artistic Directors of Music@Menlo in Silicon Valley, and of Chamber Music Today, a festival held in Seoul, South Korea. WolF Trap appointed Wu Han to serve as Artistic Advisor oF its Chamber Music at the Barns series, and this season, she is Montclair State University’s Artist in Residence. Leaders oF the classical recording industry, they created ArtistLed in 1997, the first musician-directed and internet-based classical recording company. David Finckel and Wu Han have also overseen the establishment of the CMS Studio Recordings label, the Society’s partnership with Deutsche Grammophon, CMS’s live stream programming, and Music@Menlo LIVE, which has been praised as “the most ambitious recording project of any classical music Festival in the world” (San Jose Mercury News). -

Emerson String Quartet to Play at UCSD

Emerson String Quartet to play at UCSD January 5, 1989 Contact: Ruth Baily, University Events Office, 534-4090 or Alixandra Williams, University Communications, 534-3120 THE EMERSON STRING QUARTET TO PLAY AT UCSD ON JANUARY 21 The Emerson String Quartet will play a program of Mozart, Prokofiev, Bartok and Beethoven at 8 p.m. January 21, at the University of California, San Diego's Mandeville Auditorium. The quartet's members are: Eugene Drucker, violin (first in Mozart and Prokofiev), Philip Setzer, violin (first in Bartok and Beethoven), Lawrence Dutton, viola and David Finckel, cello. The program: Prokofiev: Quartet No. 1 in B minor; Mozart: Quartet in E-Flat Major, K. 428; Bartok: Quartet No. 3 (1927) and Beethoven: Quartet in F minor, Opus 95 "Serioso." In only ten years, the Emerson String Quartet has become one of the most sought-after major ensembles, dividing its seasons among the United States, Europe and the Far East. The group celebrated its tenth anniversary by performing four complete Beethoven cycles in the United States. In Europe the quartet's performances at the Salzburg and Lucerne festivals were received with triumphant reviews. The Emerson quartet has performed more than 120 concerts annually during the last seven seasons, and has appeared in virtually every major chamber music series in North America and abroad. All four members are active in Performing Artists for Nuclear Disarmament and have presented benefit concerts for the cause of global peace and the fight against world hunger. The quartet is serving in its seventh season as resident quartet with the Lincoln Center and its ninth season with the Smithsonian Institution.