On Exhibition Without Objects — Flatness, File Size, and Hard Drives a Report by Sadia Shirazi on Her Project, Exhibition Without Objects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Danish Artists in the International Mail Art Network Charlotte Greve

Danish Artists in the International Mail Art Network Charlotte Greve According to one definition of mail art, it is with the simple means of one or more elements of the postal language that artists communicate an idea in a concise form to other members of the mail art network.1 The network constitutes an alternative gallery space outside the official art institution; it claims to be an anti-bureaucratic, anti-hierarchic, anti-historicist, trans-national, global counter-culture. Accordingly, transcendence of boundaries and a destructive relationship to stable forms and structures are important elements of its Fluxus-inspired idealistic self-understanding.2 The mail art artist and art historian Géza Perneczky describes the network as “an imaginary community which has created a second publicity through its international membership and ever expanding dimensions”.3 It is a utopian artistic community with a striving towards decentralized expansion built on sharing, giving and exchanging art through the postal system. A culture of circulation is built up around a notion of what I will call sendable art. According to this notion, distance, delay and anticipation add signification to the work of art. Since the artists rarely meet in flesh and blood and the only means of communication is through posted mail, distance and a temporal gap between sending and receiving are important constitutive conditions for the network communication. In addition, very simple elements of the mail art language gain the status of signs of subjectivity, which, in turn, become constitutive marks of belonging. These are the features which will be the focus of this investigation of the participation of the Danish artists Mogens Otto Nielsen, Niels Lomholt and Carsten Schmidt-Olsen in the network during the period from 1974–1985. -

Bern Porter Mail Art Collection, 1953-1992 (Bulk 1978-1992)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf267n98nz No online items Finding aid for the Bern Porter mail art collection, 1953-1992 (bulk 1978-1992) Finding aid prepared by Lynda Bunting. Finding aid for the Bern Porter 900270 1 mail art collection, 1953-1992 (bulk 1978-1992) ... Descriptive Summary Title: Bern Porter mail art collection Date (inclusive): 1953-1992 (bulk 1978-1992) Number: 900270 Creator/Collector: Porter, Bern, 1911-2004 Physical Description: 19.25 linear feet(39 boxes, 1 flat file folder) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California, 90049-1688 (310) 440-7390 Abstract: American physicist, poet, publisher, editor of artists' books, illustrator and mail artist. Collection consists of five collections of mail art preserved by Porter from his own accumulation and those of fellow mail artists John Pyros, Carlo Pittore (née Charles Stanley), Robert Saunders, and Jay Yager. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical/Historical Note Bern Porter was born Bernard Harden Porter on February 14, 1911 in Porter Settlement, Maine. Schooled in physics, Porter contributed to the Manhattan Project until 1945 when he quit shortly after he published Henry Miller's Murder the Murderer, an anti-war tract. Disillusioned by the misapplication of scientific potential, Porter began to express himself through a fusion of science and art. In 1959, he established the Institute for Advanced Thinking to encourage freelance physicists to develop ideas that combine physics and the humanities. -

Mail ART Exhlbltlons O COMPETITIONS

MAiL ART EXHlBltlONS O COMPETITIONS NEWS Kay Thomas, artist-in-residence, at Ross Elementary school designing the stamps for the united ~ations,Hundert- in Odessa, Texas has reported to Umbrella that there is a wasser said he tried to capture the spirit of the decla- children's Learning Disabled Class at the Elementary School ration, which was in 1948. where she works, and they have had their first exposure to Hundertwasser's vivid designs describe a series Mail Art, and they love it. Their teacher, Mrs. Hanes, is rights and freedoms that he believes are essential for quite enthusiastic and plans to give the kids one period a man's salvation. "A postage stamp is an important week to make Mail Art. So, Mail Art Network, send mail matter. Though it is very small and tiny in size, it art to Mrs. Hanes' Class, Ross Elementary School, P.O. Box bears a decisive message. stamps are the 3912, Odessa, TX 79761, and know that you are connec- measure to the cultural standing of a country.The ting children who really need encouragement-and you tiny square connects the hearts of the sender and won't believe how refreshing their mail art is! the receiver, reducing the distances. It is a bridge between people and countries. The postage stamp Guy Bleus is organizing the European Cavellini Festival passes all frontiers. It reaches men in. prisons, asy- for 1984 in Brussels. 1) Cavellini will be appointed or nomi- lums and hospitals." =hey can be purchased and nated the First President of the United States of Europe; used only in New York, Geneva and Vienna. -

Crackerjack Kid * P.O.Box 978 * Hanover * NH 903755 USA

EDITORIAL Toda la información recogida en estas páginas ha sido extraida via Internet del Electronic Museum of Mail Art, ver en estas mismas páginas las formas de acceso, como la información es totalmente gratuita, en el caso de hayas comprado este P.O.BOX solo estás pagando el precio de coste de las copias. Para dirigirse via postal al EMMA, escribir a: Crackerjack Kid * P.O.Box 978 * Hanover * NH 903755 USA Merz Mail Welcome to Electronic Museum of Mail Art (EMMA) Welcome visitors to EMMA, The Electronic Museum of Mail Art. Your guide and director at EMMA is Chuck Welch a.k.a. Crackerjack Kid. EMMA is mail art's first electronic maiibox museurn wliere the address is ttie art, the web is your key, and admission is free. Tlie nonprofit credo at EMMA is: You don't make a iiving out of mail art, you make an art out of iiving. Objectives at EMMA are: 1) introduce the electronic and (snail) mail art cornrnunities to one another; 2) develop the concept of ernailart; 3) Encourage emaiiart interactivity through visitations into EMMA's rooms, gaileries, and iibrary; 4) promote irnage exchange. EMMA's objectives reflect ongoing efforts to netlink online and offline mail art communities through the Netwarker Telenetlink 1995. i EMMA encourages you to browse through its interactive gaiieries and rooms. Lost? Begin at the Information Center and browse through EMMA's Directory. Here you'll tind the Emailart Directorv which iists current addresses of oniine emaiiartists. Now take time to meet your guide Cracker-iack Kid. The kid will lead you to the EMMA Libraq where you can read emailart zines such as the current issue of whnker Online, or browse through the contents of Eiernal Network: A Mnil Arr Antholopv. -

You've Got Mail: the Art of Michael Morris, Vincent

YOU’VE GOT MAIL: THE ART OF MICHAEL MORRIS, VINCENT TRASOV, ERIC METCALFE AND KATE CRAIG OF IMAGE BANK Béatrice Cloutier-Trépanier “If we weren’t permitted to play the game that then defined the art-world, we were not obliged to play by the rules of the game.”1 This exhibition, a foray into conceptual Canadian art of the 1960s and 1970s, focuses on mail correspondence practices. Mail art as a marginal mode of communication parallels the development of artist-run centres and the rise of alternative art forms of art as a source of institutional critique. The works of Michael Morris (b. 1942) and Vincent Trasov (b. 1947) who founded Image Bank in 1969, and Eric Metcalfe (b. 1941) in collaboration with Kate Craig, are indebted to the earlier manifestations of correspondence art. This was initiated by Fluxus, the Nouveaux Réalistes, and more directly, the New York Correspondence School promoted by the American artist Ray Johnson in the mid 1960s. Operating on the margins of the art circuit, Morris, Trasov and Metcalfe in conjunction with Kate Craig were part of a large—albeit private—network of artists that included the members of General Idea, Anna Banana in “Canadada” and a number of international artists such as Robert Filliou from France and Dana Atchley from the United States.2 This vibrant community was, as American Fluxus artist and author Ken Friedman writes, “characterized by a trenchant sense of privacy [and] a specific reaction against the exclusionary façade of art history and [its] exclusive attitudes.”3 ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 Stemming from my previous virtual exhibition, which was concerned with art and text, and how the digital transposition of text-based work can operate to heighten its original potential, this second exhibition is concerned with the use of a means of communication—the mail—as a viable artistic medium to further the exchange of ideas and visual material across geographical boundaries. -

Coffee Clutch 2 Draft 1

Name: _____________________________________________________ Date: _______ Coffee Clutch 2 draft 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 Across 33. German artist known for collages 13. A ticket in Spain 5. Term for the margin between the edge of a stamp 36. Tree portrayed on the flag of Cascadia 14. Humorous use of words alike or nearly alike in design and perforations 38. Country name of a 1974 artistamp by Jas Felter sound but different in meaning 6. Name on artistamps issued by 41 39. Mail artist founder of Padma Press who now lives 16. A method of creating images or effects by passing 7. He assembled Fluxus Postal Kits in the 1960's in Arizona paper or canvas over a smoking candle 11. Nickname for the late artist Al Ackerman 40. Artist movement critiquing reason through 17. London street artist who stages miniature figures in city settings 12. Name for a public transit bus in Buenos Aires techniques exploiting unpredictable outcomes 41. Independent country of the late mail artist Harley 19. Artistic technique of reassembling reality by 15. Wealthy Italian noted for self-historification and cutting sections from an existing image to create a new issuing "International Postage" Down one 18. Archipelago created by Seattle mail artist Robbie 1. French artist who said "Pick up anything at your 22. Name on artistamps created by Canadian mail Rudine (two words) feet." artist Jas Felter 20. -

Rollenflexibilität Und Demokratisierung in Der Kunst. Der Konzeptkünstler, Mail Artist Und Networker H

A NMERKUNGEN 1 Gespräch mit Peter Frank 2014, siehe Film. Vorwort und Dank 2 Duchamp im Interview mit Hamilton. Serge Stauffer (Hg.), Marcel Duchamp. Inter- views und Statements (Stuttgart 1992), 75–76, zit. nach Dittert, Mail Art in der DDR, 98. 1 „Der Grundsatz der ,Rollenflexibilität‘ ist ihm bis heute wichtig“, schrieb Badrutt- EINLEITUNG Schoch, „über Stock und unter Stein“. 2 Kurzbeitrag auf arttv.ch zur Ausstellung H. R. Fricker: Erobert die Wohnzimmer dieser Welt! 3 Ibid. 4 Bereits zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts wurden Versuche einer An näherung zwischen Kunst und Leben unternommen, beispielsweise durch die Gründung von Künstler- gemeinschaften. Daran schien Fricker aber weniger interessiert. Wie aus dem Inter- view mit Matthias Kuhn deutlich wird, setzte Fricker Kunst mitunter als Mittel ein, um sich über kreative Arbeit der Realität anzunähern, vgl. Kuhn, „Im Gespräch mit H. R. Fricker“, 381. 5 Seine seit 2008 entwickelten Charaktersätze, die aus einzelnen Begriffen von teils scheinbar gegensätzlichen Charaktereigenschaften bestehen, die auf einer Platte magnetisch zum Verschieben, Wegnehmen und Verteilen befestigt sind, verweisen auf dieses Konzept. 6 Siehe 49, 208–210. 7 Buchmann, „Conceptual Art“, 53. 8 Kurzbeitrag auf arttv.ch zur Ausstellung H. R. Fricker: Erobert die Wohnzimmer dieser Welt! 9 Kuhn, „Im Gespräch mit H. R. Fricker“, 375. 10 über die Verkaufsplattform etsy bietet die Firma InkyBrain im Internet T-Shirts mit Frickers Slogan my shadow is my graffiti an. Dies geschah ohne Wissen des Künstlers. Fricker erklärte via Facebook: „Keith Bates aus England hatte vor vielen Jahren eine Schrift (Font) mit Slogans, Symbolen und Bildern seiner Mail-Art Kollegen gestaltet und auf dem Internet zum persönlichen Gebrauch (kein kommerzieller Gebrauch) angeboten“, gepostet auf Frickers Facebook-Chronik am 13.03.2019. -

Representing the Eternal Network: Vancouver Artists' Publications, 1%9-73

Representing The Eternal Network: Vancouver Artists' Publications, 1%9-73 Tusa Shea B.A., University of Victoria, 2001 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of History in Art We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard OTusa Shea, 2004 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced n whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of t e author. Supervisor: Dr. Christopher Thomas ABSTRACT A number of artists' publications produced by the Vancouver-based collectives Image Bank, Ace Space Co., and Poem Company, which were circulated through Correspondence Art networks between 1%9 and 1m were crucial to the development of an "imagined community" known as the Eternal Network. This thesis uses the social, political, and art historical context specific to the development of artists' self-publishing in Vancouver as a case study. It examines how, at this particular time and place, these artists helped to build a parallel communications structure that functioned as an autonomous fictive space in which they could adhere to their anti-commodity, decentralized, and democratic ideals. Examiners: iii TABLE OF CONTENTS .. ABSTRACT. ..................................................................................II ... TABLE OF CONTENTS.. .................................................................III LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.. ............................................................. .iv INTRODUCTION. -

Danish University Colleges Zaumland. Serge Segay and Rea

Danish University Colleges Zaumland. Serge Segay and Rea Nikonova in the International Mail Art Network Greve, Charlotte Published in: Russian Literature DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ruslit.2006.06.019 Publication date: 2006 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication Citation for pulished version (APA): Greve, C. (2006). Zaumland. Serge Segay and Rea Nikonova in the International Mail Art Network. Russian Literature, 59(2-4), 445-467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ruslit.2006.06.019 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Download policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Russian Literature LIX (2006) II/III/IV www.elsevier.com/locate/ruslit ZAUMLAND. SERGE SEGAY AND REA NIKONOVA IN THE INTERNATIONAL MAIL ART NETWORK1 CHARLOTTE GREVE Abstract In the Fluxus-inspired idealistic self-understanding of the mail art network, trans- gression and a destructive relation to stable forms and structures are important ele- ments. -

A Finding Aid to the John Held Papers Relating to Mail Art in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the John Held Papers Relating to Mail Art in the Archives of American Art Jean Fitzgerald & Judy Ng Funding for the processing and digitization of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. July 30, 2009 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Biographical Material, 1990-1999............................................................. 5 Series 2: Diaries, 1990-2000................................................................................... 6 Series 3: Letters, 1973-2008................................................................................... -

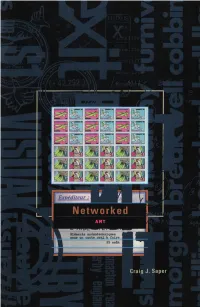

Saper, Craig J

Networked Art This page intentionally left blank Craig J. Saper Networked Art M IN NE SO University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis / London TA Copyright 2001 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota The University of Minnesota Press and the author gratefully acknowledge per- mission granted by Sackner Archive of Concrete and Visual Poetry to reprint the images that appear in this book. We also thank the following artists for their kind permission to include their work here: Vittore Baroni; J. S. G. Boggs; Guy Bleus, 42.292 Archives, The Administration Centre-T. A. C.; Ken Friedman; Augusto de Campos; Carnet Press and Edwin Morgan; Maurice Lemaître and Fondation Bismuth-Lemaître; Bob Cobbing and Writer's Forum; V. Bakhchanyan, R. Gerlovina, and V. Gerlovin for the "Stalin Test" issue images; Ed Varney; and Chuck Welch. Excerpt from "Canto XX," by Ezra Pound, from The Cantos of Ezra Pound, copyright 1934, 1938, 1948 by Ezra Pound. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. and Faber and Faber. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechani- cal, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 http: //www.upress.umn.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Saper, Craig J. Networked art / Craig J. Saper. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8166-3706-7 (HC) — ISBN 0-8166-3707-5 (PB) 1. -

Friedman MA 1995 Early Days MA 150405 Pgbk

The Early Days of Mail Art An Historical Overview Ken Friedman 1995 2015 Reprint Ken Friedman. 1995. “The Early Days of Mail Art.” Eternal Network. 2 [Start page 2] The Early Days of Mail Art: An Historical Overview Ken Friedman It is difficult to pinpoint the moment when artists’ correspondence became correspondence art. By the end of the late 1950s, the three primary sources of correspondence art were taking shape. In North America, the New York Correspondence School was in its germinal stages in the work of artist Ray Johnson and his loose network of friends and colleagues. In Europe, the group known as the Nouveau Realistes was addressing radical new issues in contemporary art. On both continents, and in Japan, artists who were later to work together under the rubric of Fluxus were testing and beginning to stretch the definitions of art. Correspondence art is an elusive art form, more variegated by nature than, say, painting. Where a painting always involves paint and a support surface, correspondence art can appear as any one of dozens of media transmitted through the mail. While the vast majority of correspondence art or mail art activities take place in the mail, today’s new forms of electronic communication blur the edges of that forum. In the 1960s, when correspondence art first began to blossom, most artists found the postal service to be the most readily available -- and least expensive -- medium of exchange. Today’s microcomputers with modern facilities offer anyone computing and communicating power that two decades ago were available only to the largest institutions and corporations, and only a few decades before that weren’t available to anyone at any price.