Folk Art and Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wotrvoices Ecopy1

www.wotr.org Experiences from the grassroots Wankute: of People, Partnerships and Perseverence anuary 15, 2011 was an unusual day for Wankute. To begin with, they were dealing with a city-like traffic situation. Their streets were more used to cycles, motorcycles Jand the occasional tractor, but today cars were lined up in every available open space. The white lines along the roads indicated an imminent arrival of an eminent person. The village kitchen was buzzing with activity; preparations were being made to feed a 1000 people. The colourful pandal flapped in the chilly January breeze, but you could barely hear its cheerful flutter over that loud speaker playing music that would eventually carry Watershed Voices across the hills and valleys of the Western Ghats. Today Wankute was celebrating. It was one of the few villages that had received an award - the JSW-TOI Earth Care Awards, an acknowledgement of all the hard work that had gone into making it a example of community led mitigation and adaptation to Climate Change. It was a happy day for WOTR too, as along with the village, WOTR was being commended and recognized for the 5 long years of committed and focused effort. Wankute had also received the Nirmal Gram Puraskar for Sanitation, an award acknowledging the cleanliness in this village, free from open defecation and overflowing sewage. But, Wankute was not always so. The Village Wankute, settled at the foothills of the Sahyadri in Western Maharashtra, was, like many of the villages around, teetering on the edge of disaster – riddled with poverty and rife with politics. -

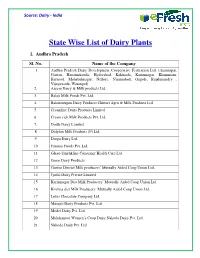

State Wise List of Dairy Plants

Source: Dairy - India State Wise List of Dairy Plants 1. Andhra Pradesh Sl. No. Name of the Company 1. Andhra Pradesh Dairy Development Cooperative Federation Ltd. (Anantapur, Guntur, Hanamakonda, Hyderabad, Kakinada, Karimnagar, Khammam, Kurnool, Mahabubnagar, Nellore, Nizamabad, Ongole, Rajahmundry , Vijayawada, Warangal) 2. Aseem Dairy & Milk products Ltd. 3. Balaji Milk Foods Pvt. Ltd. 4. Balamurugan Dairy Products Chitturi Agro & Milk Products Ltd. 5. Creamline Dairy Products Limited 6. Cream rich Milk Products Pvt. Ltd. 7. Dodla Dairy Limited 8 Dolphin Milk Products (P) Ltd. 9 Durga Dairy Ltd. 10 Fantasy Foods Pvt. Ltd. 11 Glaxo Smithkline Consumer Health Care Ltd. 12 Gosai Dairy Products 13 Guntur District Milk producers’ Mutually Aided Coop Union Ltd. 14 Jyothi Dairy Private Limited 15 Karimnagar Dist Milk Producers’ Mutually Aided Coop Union Ltd. 16 Krishna dist Milk Producers’ Mutually Aided Coop Union Ltd. 17 Lotus Chocolate Company Ltd 18 Masqati Dairy Products Pvt. Ltd. 19 Model Dairy Pvt. Ltd. 20 Mulukanoor Women’s Coop Dairy Nakoda Dairy Pvt. Ltd. 21 Nakoda Dairy Pvt. Ltd Source: Dairy - India 22 Nirma Milk Products (P) Ltd. 23 Nutrine Confectionery Co Ltd. 24 Pratap Dairy Pvt. Ltd. 25 Ravi Dairy Products (P) Ltd. 26 Sri Godavari Food Products (P) Ltd. 27 Sri Vijaya Visakha Milk Producers Company Ltd. 28 Sri Vyshnavi Foods Pvt. Ltd. 29 Steel City Foods Pvt. Ltd. 30 Tirumala Milk Pvt. Ltd. 31 Tirumala Milk Products Pvt. Ltd. 32 Upadrasta Dairy Specialities (P) Ltd. 33 Velugu Dairy Project 2. Andaman & Nicobar Sl. No. Name of the Company 1 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Integrated Development Corpn Ltd. -

IJRSS May19 Special Issue.Pdf

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 9 Issue 5, May 2019, (Special Issue) ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gate as well as in Cabell‘s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A One-Day National-Level Conference Literatures of Resistance: Voices of the Marginalised 25th April 2019 Organised by Department of English Seshadripuram College No. 27, Nagappa Street, Seshadripuram, Bengaluru – 560 020 NAAC Acreditted ‗A‘ www.spmcollege.ac.in 1 International Journal of Research in Social Sciences http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] ISSN: 2249-2496Impact Factor: 7.081 ABOUT THE CONFERENCE „I would have liked to tell you the story… Had they not slit my lips‟ --Samih al-Qassim The word ‗Resistance‘ was observed for the first time in 1996 in Palestinian Literature as written by the Palestinian writer and critic, Ghassan Kanafani. ‗Resistance‘ means to counter an ideology or action or raise objections to the existing dominant, hegemonic dogmas and practices that are hierarchical and only subjugate the inferior furthermore. Resistance is bi-dimensional, carried out both through reading and writing of texts and may be applied to a gamut of discourses such as: colonial discourse, imperial culture, gender issues, caste and class differences, imbalances due to cultural clashes and so on. Resistance has existed as long as human history and culture that it attempts to counter and will continue to exist as long as civilisation does. -

For Ahp-Pmay-Hfa

FOR AHP-PMAY-HFA SR NO. Name Father_Name Pres_Address_StreetName 1 Aabasali Raju Nadaf Raju Nadaf KATVAN KHANDOBA ROAD 2 AADIKA KUNDLIK KOLEKAR KUNDALIK SAI COLONY BALIKASHRUM ROAD BHUTKARWADI AHMEDNAGAR 3 AAFREEN MASIULLAHA SAYYED MASIULLAHA SAYYED H.NO.-E206,NATRAJ HOTEL,KRISHNA ENCLAVE,ABAD ROAD 4 AAFRIN JADED SAYYAD JAVED RAMWADI, AHMEDNAGAR 5 AAKASH ASHIK VAGGA ASHOK SHRAMIK NAGAR AHMEDNAGAR 6 AANI RAM CHAVHAN NANSHA BANDAR KALE SAMARTH NAGAR PANYACHY TAKI JAVAL NAKSHATRA LON SAMOR BURUDGAOV ROAD 7 AANIS YASIN SAYYAD YASIN 1, HUSSAIN MIYA MASID JAWAL, AHMEDNAGAR 8 AARCHANA SANTOSH JADHAV SANTOSH BHISTBAGH ROAD, ATHARV COLONY,KASABE WASTI, AHMEDNAGAR 9 AARDE DILIP SAKHARAM SAKHARAM MALIWADA WESHISAMOR, KHISTIWADA, DHORGALLI, AHMEDNAGAR 10 AAREF AKBAR SHAIKH AKBAR MARIYAM MASJID JAWAL MUKUND NAGAR 11 AAREFA BASHIR KHAN BASHIR GKHAN BADI MAJJID JAAVAL GHAR NO 5/4 JUNA MUKUNDNAGAR AHMEDNAGAR 12 AARIF RASHID SAYYAD RASHID VAIDUWADI DHANGAR VASTI,SAVEDI,AHMEDNAGAR 13 AARIFA MOHMMADALI PATHAN MOHMMADALI IRIGATION WORKSHOP SHEJARI KEDGOAN AHMEDNAGAR 14 AARIFA NISAR SHAIKH SHAIKH AJJIJ NAVAJ BHUJABAL COLONY MUKUNDNAGAR 15 AARIFA SHAFI SHAIKH HUSEN SHAIKH MASTAN SHAHA CHOWK KOTHALA ZOPADPATTI 16 Aarti Bharat Mithapara Bharat Mithapara KATVAN KHANDOBA ROAD 17 AARTI DATTA NEMANE HARI HAJARE RAVISH COLONY, KINETIC CHOWK, AHMEDNAGAR 18 AARTI LAXMAN KUKREJA LAXMAN BORUDE MALA, SAVEDI,AHMEDNAGAR 19 AARTI NARAYAN KONDE NARAYAN FAKIRWADA,MUKUNDNAGAR,AHMEDNAGAR 20 AARTI RAJENDRA SANDALSE RAJENDRA BARATOTI KARANJA,MALIWADA, AHMEDNAGAR 21 AARTI RAJESH -

Management Discussion and Analysis and Discussion Management

investing in tomorrow management discussion and analysis OVERVIEW Zee Entertainment Enterprises Limited (ZEE) (BSE Code: 505537, NSE Code: ZEEL.EQ) is one of India’s largest vertically integrated media and entertainment company. The Company was formed in 1982. ZEE was the first private company to launch a satellite channel in India and from being a single channel for a single geography today operates multiple channels across multiple geographies in different languages and genres. The Company’s programming reaches out to over 959 million viewers across 169 countries globally. ZEE channel portfolio, across various genres in the Indian market, includes: i. Hindi Entertainment: Zee TV, Zee Smile, Zee Anmol, Zindagi, &tv ii. Hindi Movies: Zee Cinema, Zee Action, Zee Classic, &pictures iii. English Entertainment, Movies and Life style: Zee Studio, Zee Café iv. Regional Language Entertainment: Zee Marathi, Zee Talkies, Zee Bangla, Zee Bangla Cinema, Zee Telegu, Zee Kannada, Zee Tamil v. Sports: TEN Sports, TEN Cricket, TEN Action, TEN Golf vi. Religious and Alternate Lifestyle: Zee Salaam vii. Music: Zing, ETC Bollywood 104 viii. Niche and Special Interest: Zee Khana Khazana, Zee Q ix. HD: Zee TV HD, Zee Cinema HD, Zee Studio HD, TEN HD, &pictures HD, &tv HD Apart from the channels listed above which are available in India, the Company also broadcasts 36 dedicated channels in the international markets. MEDIA AND ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY The Indian Media and Entertainment Industry witnessed a moderate growth in 2014. The industry grew from ` 918 billion in 2013 to ` 1,026 billion in 2014, registering a growth rate of 12%. Television sector grew from ` 417 billion in 2013 to ` 475 billion in 2014, registering a growth of 14%. -

Code Date Description Channel TV001 30-07-2017 & JARA HATKE STAR Pravah TV002 07-05-2015 10 ML LOVE STAR Gold HD TV003 05-02

Code Date Description Channel TV001 30-07-2017 & JARA HATKE STAR Pravah TV002 07-05-2015 10 ML LOVE STAR Gold HD TV003 05-02-2018 108 TEERTH YATRA Sony Wah TV004 07-05-2017 1234 Zee Talkies HD TV005 18-06-2017 13 NO TARACHAND LANE Zee Bangla HD TV006 27-09-2015 13 NUMBER TARACHAND LANE Zee Bangla Cinema TV007 25-08-2016 2012 RETURNS Zee Action TV008 02-07-2015 22 SE SHRAVAN Jalsha Movies TV009 04-04-2017 22 SE SRABON Jalsha Movies HD TV010 24-09-2016 27 DOWN Zee Classic TV011 26-12-2018 27 MAVALLI CIRCLE Star Suvarna Plus TV012 28-08-2016 3 AM THE HOUR OF THE DEAD Zee Cinema HD TV013 04-01-2016 3 BAYAKA FAJITI AIKA Zee Talkies TV014 22-06-2017 3 BAYAKA FAJITI AIYKA Zee Talkies TV015 21-02-2016 3 GUTTU ONDHU SULLU ONDHU Star Suvarna TV016 12-05-2017 3 GUTTU ONDU SULLU ONDU NIJA Star Suvarna Plus TV017 26-08-2017 31ST OCTOBER STAR Gold Select HD TV018 25-07-2015 3G Sony MIX TV019 01-04-2016 3NE CLASS MANJA B COM BHAGYA Star Suvarna TV020 03-12-2015 4 STUDENTS STAR Vijay TV021 04-08-2018 400 Star Suvarna Plus TV022 05-11-2015 5 IDIOTS Star Suvarna Plus TV023 27-02-2017 50 LAKH Sony Wah TV024 13-03-2017 6 CANDLES Zee Tamil TV025 02-01-2016 6 MELUGUVATHIGAL Zee Tamil TV026 05-12-2016 6 TA NAGAD Jalsha Movies TV027 10-01-2016 6-5=2 Star Suvarna TV028 27-08-2015 7 O CLOCK Zee Kannada TV029 02-03-2016 7 SAAL BAAD Sony Pal TV030 01-04-2017 73 SHAANTHI NIVAASA Zee Kannada TV031 04-01-2016 73 SHANTI NIVASA Zee Kannada TV032 09-06-2018 8 THOTAKKAL STAR Gold HD TV033 28-01-2016 9 MAHINE 9 DIWAS Zee Talkies TV034 10-02-2018 A Zee Kannada TV035 20-08-2017 -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1958 , 27/07/2020 Class 35 1756371 21

Trade Marks Journal No: 1958 , 27/07/2020 Class 35 1756371 21/11/2008 RELIANCE BIG ENTERTAINMENT PVT. LTD. RELIANCE ENERGY CENTRE, SANTACRUZ (EAST), WESTERN EXPRESS HIGHWAY, MUMBAI-400 055. SERVICE PROVIDER (A COMPANY INCORPORATED UNDER THE COMPANIES ACT 1956). Used Since :02/01/2008 MUMBAI ADVERTISING, BUSINESS MANAGEMENT, BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, OFFICE FUNCTIONS. 7953 Trade Marks Journal No: 1958 , 27/07/2020 Class 35 SAIGRACE 2071689 21/12/2010 SAIGRACE GIFT GALLERY R - 18, MAIN VIKAS MARG, SHAKARPUR, NEAR METRO PILLER NO. 49, DELHI - 110092 Address for service in India/Attorney address: UMA KUMARI 304, PRATAP COMPLEX, R - 20, SHAKARPUR, DELHI - 92 Proposed to be Used DELHI ADVERTISING, BUSINESS MANAGEMENT, BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, OFFICE FUNCTIONS AND ALL OTHER ITEMS MENTIONED IN CLASS 35. 7954 Trade Marks Journal No: 1958 , 27/07/2020 Class 35 Priority claimed from 14/10/2010; Application No. : 1211838 ;Benelux 2111730 08/03/2011 EDMACO INTERNATIONAL S.A. Bahnhofstrasse 10, 6300 Zug, Switzerland. SERVICE PROVIDERS Address for service in India/Attorney address: DEPENNING & DEPENNING 120, VELACHERY MAIN ROAD, GUINDY, CHENNAI - 600 032. Proposed to be Used CHENNAI ADVERTISING, BUSINESS MANAGEMENT, BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, OFFICE FUNCTIONS, IMPORT AND EXPORT AGENCIES. 7955 Trade Marks Journal No: 1958 , 27/07/2020 Class 35 2472126 05/02/2013 E-TEAM INFOCOM PRIVATE LIMITED trading as ;E-TEAM INFOCOM PRIVATE LIMITED KRIPA BHAVAN,SECTOR-5,BLOCK-EP,PLOT Y-20,SALT LAKE CITY,2ND FLOOR,KOLKATA 700091,WEST BENGAL SERVICES PROVIDER Address for service in India/Attorney address: AMIT GOYAL & ASSOCIATES P-331,SHIVAM APARTMENT,LAKE TOWN,BL-A,GROUND FLOOR,KOLKATA 700 089,WEST BENGAL,INDIA Used Since :15/06/2011 KOLKATA In respect of"^BUSINESS MANAGEMENT, BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, OFFICE FUNCTIONS" as is INCLUDED IN CLASS 35 . -

Management Discussion and Analysis

ANNUAL REPORT 2015-16 90 CONSISTENCY & CHANGE MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS INDIAN MACROECONOMIC SCENARIO In 2015, subscription revenues grew at annualized growth rate 11.4%, from INR 612 billion India is one of the few shining spots on an otherwise gloomy global economic map. While in 2014 to INR 682 billion in 2015. With the effects of cable digitization yet to show impact, most of the global economies did not fare well in the past year, the process of economic the subscription revenue is expected to grow to INR 1,266 billion by 2020 at a CAGR of recovery in India continued with the GDP growth being one of the highest in the world. 13.2% during 2015-2020. Renewed industrial activity, sustained low crude oil prices, favorable business sentiments, INDIAN MEDIA & ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY easing interest rates have spurred the economic growth. The government’s promise to stick to the fiscal deficit target for the current year and reduce it for the next year bodes well for 2014 414 612 the Indian economy. Indian GDP grew at 7.3% for FY16 and is projected to grow at 7.5% 2015 475 682 in the next fiscal year. 2016(P) 547 768 2017(P) 637 865 2018(P) 739 985 GDP GROWTH RATE OF SELECTED COUNTRIES 2019(P) 860 1120 2020(P) 994 1266 8.2 AD REVENUE SUBSCRIPTION REVENUE 7.3 7.3 7.5 7.5 7.8 Source : FICCI-KPMG Report on Indian Media & Entertainment Industry 2016 6.5 6.9 6.5 6.2 3.4 2.9 3.1 3.2 3.5 TELEVISION 2.2 2.5 Television forms the core of the Indian M&E Industry contributing to around 47% of the 2.4 2.4 2.2 2.4 2.2 1.7 0.1 2.2 0 overall revenue of the industry. -

(Ms) Membership No: Res: Mobile: Email

SUPREME COURT BAR ASSOCIATION Name & Address Name & Address 1 Wangmo,Rinchen (Ms) 5 A. Roopashri (Mrs.) Membership no: W-00060 Membership no: A-00121 Res: H.No-84, Block-B, Sector A-9, Pocket-1,Narela, Res: 3/2, St. Johns Road,, Shivan Chetty Garden Post, Delhi 110040 Bangalore 560042 Mobile: 8826232720 Tel: 080-25549660 Email: [email protected] Off: 3/2, St. Johns Road,, Shivan Chetty Garden Post, Bangalore 560042 Tel: 080-25307104 2 A. Hanumantha Reddy Mobile: 9886012342 Email: [email protected] Membership no: A-00103 Res: Plot no.28, Vivekananda Enclave, Road No.2, 6 A.Mohan Doss Banjara Hills, Hyderabad, AP 500034 Tel: 040-23744322 Membership no: A-00094 Mobile: 09849536633 Email: [email protected] Res: No-13/2, Khan Street, Choolaimedu, Chennai 600094 Tel: 044-23741149 3 A. Kalamegam V. Arumugam Ch: 71, Law Chamber, Madras High Court, Chennai 600094 Membership no: A-00090 Tel: 044-23741149 Mobile: 09884043335 Res: Old No-3, New No-7, Mosque Street, Chepauk, Channai 600005 Tel: 044-28552939 7 A.S Naushad Ch: 153, Additional Law Charmber, Madras High Court, Madras Membership no: A-00175 Mobile: 9840062370 Email: [email protected] Res: Ishel Near.B.H.S, Attingal, Trivandrum, Kerala 695101 Off: Flat No77, Tower No-13, 4th Floor,, Supreme 4 A. Raja Enlclave, M.V. Ph-1, Delhi Mobile: 9847130707 A-00811 Membership no: Email: [email protected] Res: A-33, Gulmohar Park, New Delhi 110049 Tel: 26531222-333 8 A.S. Rao Mobile: 9013180381,9999864553 Membership no: A-00575 Email: [email protected] Res: H.No.27, 3rd floor, Street No.7,, Pratap Nagar, Mayur Vihar Phase-I,, New Delhi Tel: 011-22756891 Ch: 411, M.C. -

Meat Export Policy

Vol XXXVII No 2 Summer 2014 Journal of Beauty Without Cruelty - India An International Educational Charitable Trust for Animal Rights Smuggling Live Cattle Superstitions Animal Sacrifice Special Offer for Readers Meat Export Policy Beauty Without Cruelty - India 4 Prince of Wales Drive, Wanowrie, Pune 411 040 Tel: +91 20 2686 1166 Fax: +91 20 2686 1420 From E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.bwcindia.org my Desk… he editor of Contents Compassionate Friend, Ashoke Dasgupta, From my Desk… ___________________________ this page has resigned. BWC is grateful Superstitions about Animals _______________________2 to him for having edited our Plunder of India’s Dignity ___________________________4 magazine for five years. Back to Square One __________________________6 So now, I am back as editor – Fact, not Fancy Gelatine ___________________________9 hopefully interim editor! Ekvira Devi jatra __________________________________ 10 This issue covers how many, Vegan Recipe Lotus seed ________________________ 12 where and why, India’s cattle are killed: smuggled into Bangladesh to be killed for meat and leather, and killed Beauty Without Cruelty within India for meat export. is grateful to Animal sacrifice at the Ekvira Shernaz Venkatesh Dhond Devi jatra is also included. for sponsoring this issue of Depressing, so here’s some good news. Heritage Status for Camels ` by donating 1,00,000/- BWC was pleased to receive a letter from the Rajasthan Beauty Without Cruelty Published and edited by Government saying they Diana Ratnagar were considering according is a way of life which causes Chairperson, BWC - India state heritage status to the no creature of land, sea or air Designed by Dinesh Dabholkar camel. -

Ramoshi‟ Community in Twentieth-Century Maharashtra Prof.Vikas Bhanudas Takale Ph.D

A Study of the Social life of „Ramoshi‟ Community in Twentieth-Century Maharashtra Prof.Vikas Bhanudas Takale Ph.D. scholar, Savitribai Phule Pune, University, Pune Abstract: At present, family members, their relationships, behaviors, customs are changing. As such, the unwritten and manuscript customs of the Ramoshi community are disappearing. From the time he was born in Ramoshi society till his death, various rites took place on him. Without this sacrament, he has no place in this society. There is widespread superstition in Ramoshi society. Women’s costumes, their ornaments are decorated with their ornaments today. Old-fashioned jewelry is seen on the body of some elderly women in Ramoshi community. The social conditions of the Ramoshi community of Maharashtra in the twentieth century seem to be backward according to the prevailing social system. Since the importance of education did not reach Ramoshi society, due to lack of proper educational facilities, the concept of person development did not digest. Not knowing the importance of individual development, Ramoshi remained backward in social education. And being backward in education has become a matter of routine for them, both economically and socially. Key Word: Social life, Ramoshi Community, Twentieth-Century 1. Introduction: Indian society is comprised of 2. The social life of the Ramoshi community different religions, languages, races, castes and tribes, so While writing history till date, no history has there is diversity in the social order in terms of lifestyle. been written beyond the history of Raja-Maharaja. But After 60 years of the liberation of castes and tribes in the now the history writing class is wide open. -

Marathi Newspaper App Download

Marathi newspaper app download CLICK TO DOWNLOAD app download marathi news - Get latest and breaking marathi news about app download, updated and published at 24Taas, Zee News Marathi. Marathi news by Loksatta - one of the most respected Marathi newspaper provides the connect with Maharashtra with this well-designed app to provide news and stories from the daily newspaper as well as the website (renuzap.podarokideal.ru). Get on the go access to Marathi news, breaking news, top news, live coverage, photos from Maharashtra and around the country.4,1/5(10,2K). · Download Marathi Newspaper for Android on Aptoide right now! Read Marathi newspapers in one app. Various newspapers from Maharashtra are available. Newspapers includes: Lokmat (Marathi (मराठी) - लोकमत), Loksatta (लोकसा), Operating System: Android + (Gingerbread). marathi news paper free download - Marathi News Paper New, Marathi news paper app, Marathi News Paper, and many more programs. Download this app from Microsoft Store for Windows 10 Mobile, Windows Phone , Windows Phone 8. See screenshots, read the latest customer reviews, and compare ratings for Marathi News Reader. · Download ePaper Marathi Newspaper Free App apk for Android. Todos los periódicos en línea marathi en una sola aplicaciórenuzap.podarokideal.rury: Aplicación. We Have almost all Marathi e-paper added in this app, this android app help by read and browse all marathi E-papers in this app, marathi news paper, marathi news app, marathi news, marathi news Operating System: Android. 34 rows · · 2. Download the apk file of the application you need (for example: Loksatta . Zee Marathi App is a personalized & interactive Marathi Entertainment experience for you on your mobile screen.