Historical Development of the Terminology of Spherical Astronomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Principles of Celestial Navigation James A

Basic principles of celestial navigation James A. Van Allena) Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242 ͑Received 16 January 2004; accepted 10 June 2004͒ Celestial navigation is a technique for determining one’s geographic position by the observation of identified stars, identified planets, the Sun, and the Moon. This subject has a multitude of refinements which, although valuable to a professional navigator, tend to obscure the basic principles. I describe these principles, give an analytical solution of the classical two-star-sight problem without any dependence on prior knowledge of position, and include several examples. Some approximations and simplifications are made in the interest of clarity. © 2004 American Association of Physics Teachers. ͓DOI: 10.1119/1.1778391͔ I. INTRODUCTION longitude ⌳ is between 0° and 360°, although often it is convenient to take the longitude westward of the prime me- Celestial navigation is a technique for determining one’s ridian to be between 0° and Ϫ180°. The longitude of P also geographic position by the observation of identified stars, can be specified by the plane angle in the equatorial plane identified planets, the Sun, and the Moon. Its basic principles whose vertex is at O with one radial line through the point at are a combination of rudimentary astronomical knowledge 1–3 which the meridian through P intersects the equatorial plane and spherical trigonometry. and the other radial line through the point G at which the Anyone who has been on a ship that is remote from any prime meridian intersects the equatorial plane ͑see Fig. -

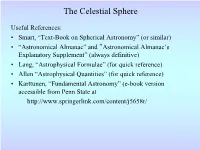

The Celestial Sphere

The Celestial Sphere Useful References: • Smart, “Text-Book on Spherical Astronomy” (or similar) • “Astronomical Almanac” and “Astronomical Almanac’s Explanatory Supplement” (always definitive) • Lang, “Astrophysical Formulae” (for quick reference) • Allen “Astrophysical Quantities” (for quick reference) • Karttunen, “Fundamental Astronomy” (e-book version accessible from Penn State at http://www.springerlink.com/content/j5658r/ Numbers to Keep in Mind • 4 π (180 / π)2 = 41,253 deg2 on the sky • ~ 23.5° = obliquity of the ecliptic • 17h 45m, -29° = coordinates of Galactic Center • 12h 51m, +27° = coordinates of North Galactic Pole • 18h, +66°33’ = coordinates of North Ecliptic Pole Spherical Astronomy Geocentrically speaking, the Earth sits inside a celestial sphere containing fixed stars. We are therefore driven towards equations based on spherical coordinates. Rules for Spherical Astronomy • The shortest distance between two points on a sphere is a great circle. • The length of a (great circle) arc is proportional to the angle created by the two radial vectors defining the points. • The great-circle arc length between two points on a sphere is given by cos a = (cos b cos c) + (sin b sin c cos A) where the small letters are angles, and the capital letters are the arcs. (This is the fundamental equation of spherical trigonometry.) • Two other spherical triangle relations which can be derived from the fundamental equation are sin A sinB = and sin a cos B = cos b sin c – sin b cos c cos A sina sinb € Proof of Fundamental Equation • O is -

On the Dynamics of the AB Doradus System

A&A 446, 733–738 (2006) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20053757 & c ESO 2006 Astrophysics On the dynamics of the AB Doradus system J. C. Guirado1, I. Martí-Vidal1, J. M. Marcaide1,L.M.Close2,J.C.Algaba1, W. Brandner3, J.-F. Lestrade4, D. L. Jauncey5,D.L.Jones6,R.A.Preston6, and J. E. Reynolds5 1 Departamento de Astronomía y Astrofísica, Universidad de Valencia, 46100 Burjassot, Valencia, Spain e-mail: [email protected] 2 Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, USA 3 Max-Planck Institut für Astronomie, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany 4 Observatoire de Paris/LERMA, Rue de l’Observatoire 61, 75014 Paris, France 5 Australian Telescope National Facility, P.O. Box 76, Epping, NSW 2121, Australia 6 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, California 91109, USA Received 4 July 2005 / Accepted 21 September 2005 ABSTRACT We present an astrometric analysis of the binary systems AB Dor A /AB Dor C and AB Dor Ba /AB Dor Bb. These two systems of well-known late-type stars are gravitationally associated and they constitute the quadruple AB Doradus system. From the astrometric data available at different wavelengths, we report: (i) a determination of the orbit of AB Dor C, the very low mass companion to AB Dor A, which confirms the mass estimate of 0.090 M reported in previous works; (ii) a measurement of the parallax of AB Dor Ba, which unambiguously confirms the long-suspected physical association between this star and AB Dor A; and (iii) evidence of orbital motion of AB Dor Ba around AB Dor A, which places an upper bound of 0.4 M on the mass of the pair AB Dor Ba /AB Dor Bb (50% probability). -

A Modern Almagest an Updated Version of Ptolemy’S Model of the Solar System

A Modern Almagest An Updated Version of Ptolemy’s Model of the Solar System Richard Fitzpatrick Professor of Physics The University of Texas at Austin Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Euclid’sElementsandPtolemy’sAlmagest . ......... 5 1.2 Ptolemy’sModeloftheSolarSystem . ..... 5 1.3 Copernicus’sModeloftheSolarSystem . ....... 10 1.4 Kepler’sModeloftheSolarSystem . ..... 11 1.5 PurposeofTreatise .................................. .. 12 2 Spherical Astronomy 15 2.1 CelestialSphere................................... ... 15 2.2 CelestialMotions ................................. .... 15 2.3 CelestialCoordinates .............................. ..... 15 2.4 EclipticCircle .................................... ... 17 2.5 EclipticCoordinates............................... ..... 18 2.6 SignsoftheZodiac ................................. ... 19 2.7 Ecliptic Declinations and Right Ascenesions. ........... 20 2.8 LocalHorizonandMeridian ............................ ... 20 2.9 HorizontalCoordinates.............................. .... 23 2.10 MeridianTransits .................................. ... 24 2.11 Principal Terrestrial Latitude Circles . ......... 25 2.12 EquinoxesandSolstices. ....... 25 2.13 TerrestrialClimes .................................. ... 26 2.14 EclipticAscensions .............................. ...... 27 2.15 AzimuthofEclipticAscensionPoint . .......... 29 2.16 EclipticAltitudeandOrientation. .......... 30 3 Dates 63 3.1 Introduction...................................... .. 63 3.2 Determination of Julian Day Numbers . .... 63 4 Geometric -

Cultural Astronomy

Bulgarian Journal of Physics vol. 48 (2021) 183–201 Cultural Astronomy S. R. Gullberg School of Integrative and Cultural Studies, College of Professional and Continuing Studies, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma 73069, USA Received July 06, 2020 Abstract. Cultural astronomy is the study of the astronomy of ancient cultures and is sometimes called the anthropology of astronomy. It is explored here in detail to demonstrate the importance of including astronomical research with field research in other fields. The many ways that astronomy was used by an- cient cultures are fascinating and they exhibit well-developed visual astronomies often used for calendrical purposes. Archaeoastronomy is interdisciplinary and among its practitioners are not only astronomers and astrophysicists, but also anthropologists, archaeologists, and Indigenous scholars. It is critical that as- tronomical data collected be placed into cultural context. Much can be learned about ancient cultures though examination of how and why they used astron- omy. KEY WORDS: Cultural astronomy, archaeoastronomy, Babylonian Astronomi- cal Diaries, Inca astronomy, Milky Way, dark constellations, astronomy educa- tion 1 Introduction Cultural astronomy examines the astronomy used in ancient cultures, including orientations found at sites and structures of ancient peoples. Archaeoastronomy is quite interdisciplinary. It employs astronomy, but as well uses elements of ar- chaeology and anthropology. Investigations commonly involve potential astro- nomical alignments, and these must be placed into cultural context for meaning. Ethnoastronomy is another branch of Cultural Astronomy and it deals with the astronomical systems of living indigenous peoples. As a resource for research, the sky has changed little since antiquity. Astronomy measures events in the sky and archaeology derives data from material evidence. -

Astronomy B.Sc

Astronomy B.Sc. Semester I (Applicable from July 2018) Paper I Spherical Astronomy Unit 1:Geometry of the sphere:Definitions and properties of Great circle, Small circle, and the Spherical triangle. Derivations of the Cosine formula, Sine formula, The Analogue formula, and Cotangent formula. Unit 2:The Celestial sphere, The coordinate systems:Azimuth \& altitude, Right ascension \& declination, Longitude \& latitude; Hour angle; Earth's diurnal motion and annual motion, Atmospheric refraction, Rising and setting of celestial bodies. Unit 3:Twilight, Sidereal time, Mean Sun, Mean time, Equation of time, and The Universal time. Unit 4:Kepler's laws, Planetary Phenomena. Books recommended: Textbook on Spherical Astronomy by W. M. Smart Textbook on Spherical Astronomy by Gorakh Prasad Paper II General Astronomy I Unit 1:The Earth: The shape, size, rotation, and revolution of the earth, Its atmosphere; Airglow and Aurora; Origin, location and observations; Geomagnetic field, Van Allen radiation belts, trapped radiation. Unit 2:The Moon: Its Motion, surface features, phases, and tides. Unit 3:The Sun: Determination of surface temperature, surface features, chromosphere, corona, solar activity cycle and rotation. Unit 4:The solar system: Bode's law, planets, asteroids, satellites, meteors, zodiacal light and Gagenchein, structure and physics of comets, Properties and origin of solar system. Books recommended: Introduction of Astronomy by Fredrick and Baker Introduction to Astronomy by C. Payne Gaposhkin Astronomy B.Sc. Semester II (Applicable from January 2019) Paper III General Astronomy II Unit 1:Elementary ideas about formation of stars, Magnitudes and colors of stars, Apparent, absolute and bolometric magnitudes of stars, Luminosity of stars. Unit 2:Distances of stars: Trigonometrical parallax, Moving cluster method, Spectroscopic parallax; Determination of stellar mass and temperature; Elementary ideas about stellar systems: clusters of stars; Galaxies: shapes and sizes. -

What Every Young Astronomer Needs to Know About Spherical Astronomy: Jābir Ibn Aflaḥ's “Preliminaries” to His Improveme

What every young astronomer needs to know about spherical astronomy: Jābir ibn Aflaḥ’s “Preliminaries” to his Improvement of the Almagest J. L. Berggren1 Abū Muḥammad Jābir b. Aflaḥ is believed to have worked in Seville in the first half of the 12th century during the reign of the Almoravids. His best-known work is his astronomical treatise, the “Improvement of the Almagest” (Iṣlaḥ al-majisṭī). It was the first serious, technical improve- ment of Ptolemy’s work to be written in the Islamic west and it reveals Jābir as an accomplished theoretical astronomer, one devoted to logical exposition of the topic. This paper focuses on the First Discourse of Jābir’s work, which establishes the mathematical preliminaries needed for the study of astronomy based on the geometric models of heavenly bodies (Sun, Moon, planets and stars) revolving around a spherical Earth. Early in his Improvement, Jābir states that one of his goals in writing the book is to write an astronomical work that would—apart from reliance on Euclid’s Elements—stand on its own as re- gards the necessary mathematics. He specifically mentions that he has obviated the need for the works of the ancient writers, Theodosius and Menelaus. In the case of Theodosius, Jābir meant that the reader would not have to refer to the Greek author’s Spherics since Jābir has selected from Books I and II of that work statements and proofs of theorems necessary for an astronomer. However, he did assume that his reader would have some basic knowledge of spherics2 since such basic results as Sph. -

Library Catalogue 2000, by Author

A B C D E F G H I J 1 alastname afirstname title dewey_ydoeuwtey_nudmewey_ldeetwey_nopteublisher year notes 2 AAAS "The Moon Issue" of Science, Jan 30/1970 523.34 S 1970 3 AAVSO Variable Comments 523.84 A Cambridge: AAVSO 1941 4 Abbe Cleveland Short Memoirs on Meteorological Subjects 551.5 A Washington: Govt Printing Office1878 5 Abbot Charles G. The Earth and the Stars 523 A Copy 1 New York: Van Nostrand 1925 6 Abbot Charles G. The Sun 523.7 A Copy 2 New York: Appleton 1929 7 Abell George O. Exploration of the Universe 523 A 3rd ed. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winst1o9n75 8 Abercromby Ralph & Goldie Weather 551.55 A London: Kegan Paul 1934 9 Abetti Giorgio Solar Research 523.7 A New York: MacMillan 1963 Abetti, Giorgio 1882-. 173p. illus 21cm (A survey of astronomy) 10 Abetti Giorgio The History of Astronomy 520.9 A New York: Henry Schuman 1952 Abetti, Giorgio, 1882- 11 Abetti Giorgio The Sun 523.7 A Copy 2 London: Faber and Faber 1957 Abetti, Giorgio 1882-. Translated by J.B. Sidgwick 12 Abro A. The Evolution of Scientific Thought From Newton to Einstein 530.1 A New York: Dover Publications 1950 481p. ports,diagrs 21cm. No label on spine. 13 Achelis Elisabeth The World Calendar 529.5 A New York: G.P. Putnum's sons 1937 Achelis, Elisabeth, 1880-. The world calendar; addresses and occasional papers chronologically arranged on the progress of calendar reform since 1930. 189p. pl.,double tab. 21cm "Explanatory notes" on slip inserted before p.13. 14 Adams John Couch The Scientific Papers of John Couch Adams, Vol. -

Positional Astronomy : Earth Orbit Around Sun

www.myreaders.info www.myreaders.info Return to Website POSITIONAL ASTRONOMY : EARTH ORBIT AROUND SUN RC Chakraborty (Retd), Former Director, DRDO, Delhi & Visiting Professor, JUET, Guna, www.myreaders.info, [email protected], www.myreaders.info/html/orbital_mechanics.html, Revised Dec. 16, 2015 (This is Sec. 2, pp 33 - 56, of Orbital Mechanics - Model & Simulation Software (OM-MSS), Sec 1 to 10, pp 1 - 402.) OM-MSS Page 33 OM-MSS Section - 2 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------13 www.myreaders.info POSITIONAL ASTRONOMY : EARTH ORBIT AROUND SUN, ASTRONOMICAL EVENTS ANOMALIES, EQUINOXES, SOLSTICES, YEARS & SEASONS. Look at the Preliminaries about 'Positional Astronomy', before moving to the predictions of astronomical events. Definition : Positional Astronomy is measurement of Position and Motion of objects on celestial sphere seen at a particular time and location on Earth. Positional Astronomy, also called Spherical Astronomy, is a System of Coordinates. The Earth is our base from which we look into space. Earth orbits around Sun, counterclockwise, in an elliptical orbit once in every 365.26 days. Earth also spins in a counterclockwise direction on its axis once every day. This accounts for Sun, rise in East and set in West. Term 'Earth Rotation' refers to the spinning of planet earth on its axis. Term 'Earth Revolution' refers to orbital motion of the Earth around the Sun. Earth axis is tilted about 23.45 deg, with respect to the plane of its orbit, gives four seasons as Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter. Moon and artificial Satellites also orbits around Earth, counterclockwise, in the same way as earth orbits around sun. Earth's Coordinate System : One way to describe a location on earth is Latitude & Longitude, which is fixed on the earth's surface. -

Spherical Astronomy of the Indian Classical Astronomy

Spherical astronomy of the Indian Classical Astronomy (インド古典天文学の球面天文学) Yukio Ôhashi (大橋由紀夫) 3-5-26, Hiroo, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo 150-0012, Japan e-mail: [email protected] I. Introduction I have presented two papers on the history of Indian astronomy in a conference and a seminar at NAOJ, namely, Ôhashi (2011a) on the Vedāṅga astronomy, and Ôhashi (2011b) on the planetary theory of the Classical Siddhānta astronomy. The present paper is a kind of continuation of these papers. I would like to discuss the spherical astronomy of the Classical Siddhānta astronomy, where orthographic projection and plane trigonometry are used. The history of Indian astronomy can roughly be summarised as follows. [For an overview of Indian astronomy, see Ôhashi (1998) in Japanese or more detailed Ôhashi (2009) in English.] (i) Indus civilisation period (ca.2600BCE – ca.1900 BCE). (ii) Vedic period (ca.1500 BCE – ca.500 BCE). (iii) Vedāṅga astronomy period (From sometime between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE up to sometime between the 3rd and 5th centuries CE?). (iv) Period of the introduction of Greek astrology and astronomy (Sometime around the 3rd and 4th century CE?). (v) Classical Siddhānta period (Classical Hindu astronomy period). (From the end of the 5th century up to the 12th century). (vi) Coexistent period of the Hindu astronomy and Islamic astronomy (From the 13/14th century up to the 18/19th century). (vii) Modern period (Coexistent period of the modern astronomy and traditional astronomy). (From the 18/19th century onwards). Around the 3rd (?) century CE, Greek horoscopic astrology was introduced into India, and around the 4th (?) century CE, Greek mathematical astronomy seems to have been introduced into India. -

Meteors and How to Observe Them Handbook of Practical Astronomy

118 General Science Springer News 8/2008 springer.com/booksellers R. Lunsford, American Meteor Society, Chula Vista, R. Mollise, Mobile, AL, USA G. D. Roth, Icking, Germany (Ed.) CA, USA Choosing and Using the Handbook of Practical Meteors and How to New CATS Astronomy Observe Them Getting the Most from Your Schmidt Cassegrain or Other Catadioptric Telescopes The Compendium of Practical Astronomy is The focus of this book is to introduce the novice unique. The practical astronomer, whether student, to the art of meteor observing. It explains in Choosing and Using the New CATS will super- novice or accomplished amateur, will find this straightforward language how best to view meteor cede the author’s successful Choosing and Using a handbook the most comprehensive, up-to-date activity under a variety of conditions, regardless of Schmidt-Cassegrain Telescope, which has enjoyed and detailed single guide to the subject available. the observer’s location. The observing conditions enthusiastic support from the amateur astronomy It is based on Roth’s celebrated German language for each meteor shower are vastly different from community for the past seven years. handbook for amateur astronomers, which first each of the Earth‘s regions and this book would be Since the first book was published, a lot has appeared over 40 years ago. valuable to any potential observer from Australia changed in the technology of amateur astronomy. With amateurs and students and teachers of to Alaska. The sophistication and variety of the telescopes astronomy in high schools and colleges particu- The calendar chapters list activity as it occurs available to amateurs has increased dramatically. -

Solar System Astronomy Notes

Solar System Astronomy Notes Victor Andersen University of Houston [email protected] May 19, 2006 Copyright c Victor Andersen 2006 Contents 1 The Sky and Time Keeping 2 2 The Historical Development of Astronomy 10 3 Modern Science 21 4 The Laws of Motion and Gravitation 23 5 Overview of the Solar System 31 6 The Terrestrial Planets 35 6.1 The Earth . 36 6.2 The Moon . 46 6.3 Mercury . 52 6.4 Venus . 55 6.5 Mars . 58 7 The Gas Giant Planets and Their Ring Systems 62 8 The Large Moons of the Gas Giants 71 9 Minor Solar System Bodies 76 10 The Outer Solar System 82 11 The Sun and Its Influence in the Solar System 85 12 Life Elsewhere in the Solar System 92 13 The Formation of the Solar System 95 1 Chapter 1 The Sky and Time Keeping Constellations • Constellations are areas on the sky, usually defined by distinctive group- ings of stars (Modern astronomers define 88, if you are interested a complete list is given in appendix 11 of the textbook). Constellations have boundaries in the same way that countries on the earth do. • Prominent groupings of stars that do not comprise an entire constel- lation are called asterisms (for example, the Big Dipper is just part of the constellation Ursa Majoris). Star Names • Most bright stars have names (usually Arabic). • Stars are also named using the Greek alphabet along with the name of the constellation of which the star is a member. The first five lower case letters of the Greek alphabet are: α (alpha), β (beta), γ (gamma), δ (delta), and (epsilon).