Gestational Surrogacy from Human Reproduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuesday, 21 April 2020 HFEA Teleconference Meeting • Members

Tuesday, 21 April 2020 HFEA Teleconference Meeting Panel members Richard Sydee (Chair) Director of Finance and Resources Kathleen Sarsfield Watson Communications Manager Niamh Marren Regulatory Policy Manager Members of the Executive Bernice Ash Secretary External adviser Observers Catherine Burwood Licensing Manager • Members of the panel declared that they had no conflicts of interest in relation to this item. • 9th edition of the HFEA Code of Practice. • Standard licensing and approvals pack for committee members. The panel considered the papers, which included a completed application form, inspection report and licensing minutes for the last three years. The panel noted that Bourn Hall Clinic Wickford has been licensed by the HFEA since July 2018, for the standard period of two years for new licences. The centre provides a full range of fertility services. Other licensed activities of the centre include storage of gametes and embryos. The panel noted that Bourn Hall Clinic Wickford is part of a group that incorporates three other HFEA licensed centres: Bourn Hall Clinic (centre 0100), Bourn Hall Clinic Colchester (centre 0188), Bourn Hall Clinic Norwich (centre 0325). All clinics are centrally managed and have common practices and procedures, in particular their quality management system (QMS). The panel noted that the centre was last inspected in May 2019, shortly after the inspection of sister clinic, centre 0188, during which a number of anomalies in consent to legal parenthood were identified. This is discussed in detail in the renewal inspection report for centre 0188. As a result, the executive held a management review meeting, in accordance with the HFEA’s Compliance and Enforcement Policy. -

The Impact of Withdrawing Funding for Ivf

THE IMPACT OF WITHDRAWING FUNDING FOR IVF Feedback to the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough CCG regarding the impact of withdrawing NHS funding for IVF and a proposal from Bourn Hall to improve fertility service provision in the region. APRIL 2019 CONTENTS Executive summary ............................................................................................ 2 Results of the survey .......................................................................................... 3 FOI data/Bourn Hall data ................................................................................... 5 Recommendations ............................................................................................. 7 Appendix A: The Bourn Hall integrated fertility pathway ................................... 8 Appendix B: Survey results analysis .................................................................... 9 Appendix C: Impact of infertility on mental health ........................................... 11 Appendix D: Survey participants’ detailed feedback How has infertility affected you, your relationships and your health (or those of someone you care about)?............................................... 13 Appendix E: Survey participants’ advice What advice would you give your younger self regarding fertility treatment? .................. 26 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background In August 2017 Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Clinical Commissioning Group (C&PCCG) made the decision to remove funding for its Specialist Fertility Services, which includes IVF, -

Fertility Network UK Magazine – Autumn 2016

INUK Autumn 2016.e$S_Layout 1 11/10/2016 10:21 Page 1 No.51 Autumn 2016 The national charity, here for anyone who has ever experienced fertility problems NHS Funding Fundin g for NHS fertility treatmen the country, with access entir your postcode. t var ely dependies across ent on Information aby, you can find If you are trying to have a b rmation about fertility problems, treatment info upport here. options, funding and emotional s News News art parents icles f or those trying to become Support Our support network is here to offer those affected by fertility issues the support and understanding they need, when they need it. Events We have details of events which are free to attend and we will also list details of open days and free patient events for clinics who are members of our clinic outreach scheme. Our new website will be launched at The Fertility Show in November: www.fertilitynetworkuk.org INUK Autumn 2016.e$S_Layout 1 11/10/2016 10:23 Page 2 Fertility Network UK Susan Seenan Staff Gallery Chief Executive [email protected] Tel: 01294 230730 Mobile: 07762 137786 Sheena Andrew Coutts Catherine Hill Gillian Young Business Media McLaughlin Head of Development Relations Volunteer Business Manager Officer Co-ordinator Development [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Mobile: 07710 764162 Mobile: 07794 372351 Mobile: 07469 660845 Mobile: 07909 686874 Head Office Claire Heritage Alison Hannah Head Office Onash Tramaseur Manager Administrator -

Agenda Item 8.0A

Agenda Item 8.0a PART I MEETING OF THE CASTLE POINT & ROCHFORD CLINICAL COMMISSIONING GROUP GOVERNING BODY ON 29th MAY 2014 SPECIALIST FERTILITY SERVICES Submitted by: Kevin McKenny, Chief Operating Officer Prepared by: Emily Hughes, Head of Commissioning Status: For Approval EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i. Recommendations Members of the Governing Body are invited to approve the changes to the Specialist Fertility Services policy for south Essex. ii. Overview Until March 2013 specialist fertility services, including In-vitro fertilisation (IVF), Intra- cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), and Donor Insemination (DI) were commissioned by the East of England Specialised Commissioning Group (EoE SCG). In April 2013, commissioning responsibility for specialist fertility services transferred to CCGs. East and North Hertfordshire CCG (ENCCG) are the lead CCG for contracting and commissioning specialist fertility services on behalf of all the CCGs in the East of England region (EoE). The EoE policies were adopted by the CCG and have remained in place across Essex until now, pending review. NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) clinical guidance on Fertility was recently updated in February 2013, Fertility CG156 updates and replaces NICE clinical guideline 11 published in 2004. The publication of the NICE update, which differs from the currently used EoE fertility guidelines, has given rise to variation in interpretation and commissioning of the service. The intention of this paper is to outline the key differences between the current EoE policy and the NICE update and to ask for approval to accept the updated policy across south Essex. This is particularly significant at this time as the region is about to begin a procurement exercise for the provision of specialist fertility services. -

Full Programme

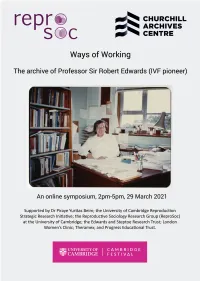

Ways of Working online symposium programme 2.00pm-2.05pm Welcome from Allen Packwood, Director of Churchill Archives Centre. 2.05pm-2.35pm Madelin Evans (Edwards Papers Archivist, Churchill Archives Centre) and Professor Nick Hopwood (Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge) in conversation about using the archive of Robert Edwards for research. 2.35pm-3.05pm Professor Sarah Franklin (Reproductive Sociology Research Group, University of Cambridge) and Gina Glover (Artist, creator of Art in ART: Symbolic Reproduction exhibition) on working with images of reproduction in the Edwards archive. 3.05pm-3.15pm Break, with the chance to view a film of Art in ART: Symbolic Reproduction exhibition by Gina Glover 3.15pm-3.45pm Dr Kay Elder (Senior Research Scientist, Bourn Hall Clinic) and Dr Staffan Müller-Wille (University Lecturer, Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge) on using clinical research notebooks, and scientific notebooks and manuscripts, for historical research. 3.45pm-4.15pm Professor Sir Richard Gardner (Emeritus Royal Society Research Professor in the University of Oxford) and Professor Roger Gosden (lately Professor at Cornell University, now Visiting Scholar at William & Mary and official biographer of Robert Edwards) on Robert Edwards’ style of working in the laboratory. 4.15pm-4.30pm Dr Jenny Joy (daughter of Robert Edwards, key in gathering together his archive) will talk about her experience of how her father worked. 4.30pm-5pm Concluding remarks, questions and discussion The Papers of Professor Sir Robert Edwards, at Churchill Archives Centre The archive comprises 141 boxes of personal and scientific papers including correspondence, research and laboratory notebooks, draft publications and journal articles, newspaper clippings, photographs, videos and film. -

The Oldham Notebooks: an Analysis of the Development of IVF 1969¬タモ

Reproductive BioMedicine and Society Online (2015) 1,3–8 www.sciencedirect.com www.rbmsociety.com SYMPOSIUM: THE HISTORY OF THE FIRST IVF BIRTHS The Oldham Notebooks: an analysis of the development of IVF 1969–1978. I. Introduction, materials and methods Kay Elder a, Martin H Johnson b,⁎ a Bourn Hall Clinic, Bourn, Cambridge CB23 2TN; b Anatomy School and Centre for Trophoblast Research, Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3DY, UK * Corresponding author. E-mail addresses: [email protected] (K. Elder), [email protected] (M.H. Johnson). Kay Elder joined Bourn Hall in 1984 as Clinical Assistant to Patrick Steptoe, directing the Out-Patient Department from 1985 – 1987. Her scientific background as a research scientist at Imperial Cancer Research Fund prior to a medical degree at Cambridge University naturally led her to Bob Edwards and the IVF laboratory, where she worked as a senior embryologist from 1987. A programme of Continuing Education for IVF doctors, scientists and nurses at Bourn Hall was established in 1989, which she directed for 16 years. During this period she also helped to set up and run two Master’s degree programmes in Clinical Embryology, and she continues to mentor and tutor postgraduate students of Clinical Embryology at the University of Leeds. In her current role as Senior Research Scientist at Bourn Hall she co-ordinates research collaborations with the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge and the MRC National Institute for Medical Research in Mill Hill. Abstract In this introductory paper, we describe the primary source material studied in this Symposium, namely a set of 21 notebooks and 571 pages of loose sheets and scraps of paper, which, on cross-referencing, have allowed us to reconstruct the sequence, timing and numbers of the laparoscopic cycles planned, attempted and undertaken between 9 January 1969 and 1 August 1978 by Robert Edwards, Patrick Steptoe and Jean Purdy in Oldham, UK, as well as to identify most of the patients involved. -

IVF Treatment in the East of England

Approved IVF clinics Oxford Fertility Unit Where do patients from the east Institute of Reproductive Sciences, for patients in the Oxford Business Park North Oxford, Oxfordshire, OX4 2HW of England receive IVF Treatment east of England Tel: 01865 782 800 [email protected] The NHS and private fertility centres listed below provide www.oxfordfertilityunit.com IVF treatment for people living in the east of England. Bourn Hall Clinic Bourn Hall Clinic, Bourn, The Barts and the London Centre You can choose from any one of these centres and your Cambridge, CB23 2TN for Reproductive Medicine NHS gynaecology consultant will be able then to refer you. Tel: 01954 719111 2nd floor, Kenton and Lucas Wing, www.bourn-hall-clinic.co.uk St Bartholomew’s Hospital, West Smithfield, London, EC1A 7BE The Leicester Fertility Centre Tel: 020 7601 7176 or 020 7601 8515 Location Provider Funding Outreach Clinics Assisted Conception Unit, Kensington [email protected] Building, Leicester Royal Infirmary, www.bartsandthelondon.nhs.uk/fertility Infirmary Square, Leicester, LE1 5WW Tel: 0116 2585922 IVF Hammersmith [email protected] Hammersmith Hospital, Du Cane Rd, Colchester IVF Treatment in Bourn Hall www.leicesterfertilitycentre.org.uk London W12 0HS Cambridge NHS Great Yarmouth Clinic Tel: 0208 383 4900 Kings Lynn www.ivfhammersmith.com the East of England The Leicester Leicester NHS No outreach centre Your questions answered Fertility Clinic Information & support Herts & Essex Fertility The following organisations can also assist you with Oxford Centre, Cheshunt information and advice on infertility and IVF treatment Oxford NHS Fertility Unit The Rosie Hospital, The East of England Specialised National Institute for Health Cambridge Commissioning Group (SCG) and Clinical Excellence (NICE) This independent organisation is The Barts and Commissions services, including IVF, on behalf of all 13 East of England responsible for providing national the London Primary Care Trusts (PCTs). -

List of Designated Bodies Below You Will Find an A-Z List of Designated Bodies (DB), Their Responsible Officer (RO) and the DB Email Address That We Hold

List of designated bodies Below you will find an A-Z list of designated bodies (DB), their Responsible Officer (RO) and the DB email address that we hold. Please take care when using the following email addresses, especially if you intend to send confidential information. Sometimes the email addresses we hold become out of date. Please check with the intended recipient if in doubt. If there is no email address it is because we do not hold one. We have approved a number of suitable persons. You can find our list of GMC approved suitable persons at: http://www.gmc-uk.org/Revalidation___Suitable_Person_details___DC4964.pdf_53912287.pdf We update this list on a weekly basis. This list was last updated on 20 September 2021. Details of responsible officers are provided to the GMC by each designated body. The GMC is not responsible for the appointment of responsible officers. If you have any queries regarding the responsible officer details for an individual designated body please contact the designated body. RO Title RO First Name RO Last Name RO UID DB Email Address 21st Century Clinic Ltd Dr Philip Dobson 3279643 [email protected] 4 Ways Healthcare Ltd Dr John Timmis 2273581 [email protected] 4Recruitment Services Ltd Dr Timothy Nuthall 3691263 [email protected] 58 Queen Square Mr Nigel Mercer 2626770 [email protected] Abicare Health Solutions Ltd Dr Harrison Offiong 7059321 [email protected] ABL Health Ltd Dr Francis Andrews 3334715 [email protected] About Health Ltd Dr Uma Krishnamoorthy 4754750 [email protected] -

History of Clinical IVF

Knowing Where We Came From: History of Clinical IVF Thomas B. Pool, Ph.D., HCLD Fertility Center of San Antonio San Antonio, Texas Disclosures “The vast majority of human beings dislike and even actually dread all notions with which they are not familiar…Hence, it comes about that at their first appearance, innovators have generally been persecuted, and always, derided as fools and madmen.” Aldous Huxley author Brave New World, 1932 “Most human beings have an almost infinite capacity for taking things for granted”. Acknowledgements I want to thank the following individuals for their altruism and assistance in preparing this presentation for the College of Reproductive Biology: Peter Brinsden (l) with James Watson and Bob Edwards Lucinda Veeck Gosden Kay Elder Professor Sir Richard L. Gardner Jacques Cohen Cohen, Jacques, 2013. From Pythagoras and Aristotle to Boveri and Edwards: a history of clinical embryology and therapeutic IVF. In: Textbook of Clinical Embryology (Coward K., Wells, D.,eds) Cambridge University Press, p177-102. Henry Leese The early history of IVF 1 • Aristotle (384-322 BC) proposed the theory that children are a product of “the mingling of male and female seed”. This opposed the prevailing theory that children were from the male seed and women merely the “receptacle for the child”. • William Harvey (1578-1657) studied the fertility of the King’s herd of deer, and wrote: “De generatione animalium” in1651, in which occurs the well known phrase: “Ex ovo omnia” – “from the egg is everything”. • Antonj van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) carried out the first studies on human sperm with the newly invented microscope. -

45.13-IVF-Consultant-Pack

EAST OF ENGLAND SPECIALISED COMMISSIONING GROUP SPECIALISED COMMISSIONING TEAM IVF Services for East of England Patients as of May 1st 2009 EAST OF ENGLAND SPECIALISED COMMISSIONING GROUP SPECIALISED COMMISSIONING TEAM Contents 1. Introduction 2. Policy and criteria 3. Barts and the London 4. Bourn Hall 5. Hammersmith 6. Leicester 7. Oxford 8. Links EAST OF ENGLAND SPECIALISED COMMISSIONING GROUP SPECIALISED COMMISSIONING TEAM -1- Introduction The East of England IVF policy and criteria was implemented from the 1st of May 2009, under the management of the East of England Specialised Commissioning Group. As from that date all couples with in the East of England that are eligible may now be entitled up to 3 fresh NHS IVF cycles. It is now also possible for all couples to be referred by their NHS consultant to any one of our 5 chosen centres .They are as follows Barts and the London Centre for Reproductive Medicine, Bourn Hall Clinic, IVF Hammersmith, Leicester Fertility Centre and Oxford Fertility Unit. Within this information pack you will find details of the policy and criteria and also information on all of the 5 centres, which we hope will be of use. EAST OF ENGLAND SPECIALISED COMMISSIONING GROUP SPECIALISED COMMISSIONING TEAM East of England Specialist Commissioning Group Fertility Treatment Policy EAST OF ENGLAND SPECIALISED COMMISSIONING GROUP SPECIALISED COMMISSIONING TEAM -2- EAST OF ENGLAND SPECIALIST COMMISSIONING GROUP FERTILITY TREATMENT AND REFERRAL CRITERIA FOR TERTIARY LEVEL ASSISTED CONCEPTION 1. INTRODUCTION This commissioning policy sets out the criteria for access to NHS funded specialist fertility services for the population of the East of England, along with the commissioning responsibilities and service provision. -

Patient Information Fertility

Patient Information Fertility Women’s Services Introduction This leaflet is for women and their partners in East and North Hertfordshire who are trying for a baby and having difficulty getting pregnant. General Information Around one in seven couples may have difficulty conceiving. This is approximately 3.5 million people in the UK. Some women conceive (get pregnant) quickly, but for others it can take longer. For every 100 couples trying to conceive naturally: 84 will conceive within one year 92 will conceive within two years 93 will conceive within three years It’s a good idea for a couple to visit their GP if they have not conceived after one year of trying. Women aged 36 and over, and anyone who is already aware they may have fertility problems, should see their GP sooner. The GP can check for common causes of fertility problems and suggest treatments that could help. For couples who have been trying to conceive for more than three years without success, the likelihood of pregnancy occurring within the next year is 25% or less. When a couple cannot get pregnant (conceive), despite having regular unprotected sex, this is known as infertility. 2 Infertility The diagnosis of infertility is made when a couple have been trying for a baby for one year and have been unable to become pregnant. There are two types of infertility: Primary Infertility – where someone who has never conceived a child in the past has difficulty conceiving. Secondary Infertility – where a person has had one or more pregnancies in the past, but is having difficulty conceiving again. -

In Vitro Human Embryos: Interdisciplinary Reflections on the First 4 Decades

In Vitro Human Embryos: Interdisciplinary reflections on the first 4 decades The Yusuf Hamied Centre Christ’s College, Cambridge 10.00-18.00 February 14th 2009 Christ’s College Cover photograph: Bunny Austin, Barbara Rankin, Bob Edwards & Jean Purdy, in the Marshall Lab in the early 1970’s Peter Braude Jacques Cohen Kay Elder Sarah Franklin Richard Gardner Emily Jackson Lisa Jardine Martin Johnson Onora O’Neill Marilyn Strathern Marina Warner Mary Warnock Photo Credits Marina Warner - John Batten Marilyn Strathern - Andrew Houston Introduction In Vitro Human Embryos: Interdisciplinary reflections on the first four decades Welcome to a meeting that is both commemorative and historical. The juxtaposition of these two functions is full of tension. Commemorations are occasions for joyful celebration, but they can also be dangerous academically, helping to sustain or create myths. Histories aim to expose and destroy myths and replace them with new, albeit provisional, truths. For example, there is an often articulated belief that the 1969 Nature paper was, in a neat touch of “Natural” editorial irony, published on St Valentine’s day - hence the date of this meeting. However, the actual date on the paper is 15th February 1969! A first myth destroyed? This meeting seeks to examine both the importance of a particular scientific publication and a wider social process of coming to terms with the in vitro human embryo, the birth of IVF, and the rapid expansion of new assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) worldwide that have emerged from it over the past 40 years. The questions we have asked our speakers to consider concern the ways in which different disciplines have responded to or been affected by this sea change in science and the accompanying social attitudes and values.