LA Times James Reed Articles on Bobbie Gentry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RSD 2021 Consumentenlijst 8 Juli Herwin.Xlsx

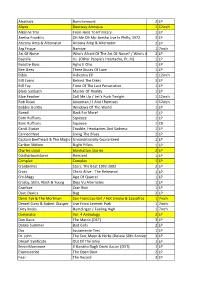

Alcatrazz Born Innocent 2 LP Aliens Doorway Amnesia 1 12inch Alkaline Trio From Here To Infirmary 1 LP Aretha Franklin Oh Me Oh My: Aretha Live In Philly, 1972 2 LP Arizona Amp & Alternator Arizona Amp & Alternator 2 LP Arp Frique Namiye 1 7inch Art Of Noise Who's Afraid Of The Art Of Noise? / Who's Afraid 2OfLP Goodbye? Bastille Vs. (Other People's Heartache, Pt. III) 1 LP Beastie Boys Aglio E Olio 1 LP Bee Gees Three Kisses Of Love 1 LP Bibio Vidiconia EP 1 12inch Bill Evans Behind The Dikes 3 LP Bill Fay Time Of The Last Persecution 1 LP Black Sabbath Master Of Reality 1 LP Blue Feather Call Me Up / Let's Funk Tonight 1 12inch Bob Dylan Jokerman / I And I Remixes 1 12inch Bobbie Gentry Windows Of The World 1 LP Bored! Back For More! 1 LP Born Ruffians Squeeze 1 LP Born Ruffians Squeeze 1 CD Candi Staton Trouble, Heartaches And Sadness 1 LP Canned Heat Living The Blues 2 LP Captain Beefheart & The Magic BandUnconditionally Guaranteed 1 LP Carlton Melton Night Pillers 1 LP Charles Lloyd Manhattan Stories 2 LP Coldharbourstores Remixed 1 LP Complex Complex 1 LP Cranberries Stars: The Best 1992-2002 2 LP Crass Christ Alive - The Rehearsal 1 LP Cro-Mags Age Of Quarrel 1 LP Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young Deja Vu Alternates 1 LP Czarface Czar Noir 1 LP Dave Davies Bug 2 LP Deniz Tek & The Mortmen San Francisco Girl / Hot Smoke & Sassafras 1 7inch Denzel Curry & Robert Glasper Live From Leimert Park 1 7inch Dirty Knobs Humdinger / Feeling High 1 7inch Dominator Vol. -

THE WORLD PREMIERE CONCERT FILM of F*CK7THGRADE BEGINS STREAMING on JANUARY 25Th Singer/Songwriter Jill Sobule Shares Her Rock & Roll Life Story on Screen

CONTACT: Nikki Battestilli Marketing Director [email protected] CityTheatreCompany.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE WORLD PREMIERE CONCERT FILM OF F*CK7THGRADE BEGINS STREAMING ON JANUARY 25th Singer/Songwriter Jill Sobule Shares Her Rock & Roll Life Story On Screen Performers: Jill Sobule, Kristen Henderson, Sarah Siplak, and Julie Wolf Pittsburgh, PA (January 10, 2021): As the Covid-19 pandemic continues to prevent a safe return to indoor performances, City Theatre is excited to announce the world premiere concert film of F*ck7thGrade. F*ck7thGrade began its journey at City Theatre three years ago when Associate Artistic Director and dramaturg Clare Drobot met singer/songwriter Jill Sobule in New York. City Theatre paired Ms. Sobule with playwright Liza Birkenmeier, who wrote the book for the show, and workshopped and presented what would become F*ck7thGrade in the theater’s 2018 Momentum Festival of New Plays. After adding OBIE Award-winning director Lisa Peterson and music director Julie Wolf to the creative team, the show was further developed at the Colorado New Play Festival in Steamboat Springs and at Actor’s Express in Atlanta, supported by the National New Play Network. The world premiere production was slated as the final show of City Theatre’s 2019/20 season when the Covid-19 pandemic stopped live performances across the country. The team at City Theatre created an outdoor, drive-in venue at Hazelwood Green and staged the concert version of the show over three nights in front of an invited audience. Videographers Mickey and Molly Miller of Human Habits captured the show live and served as editors, working closely with the directors, sound engineer Brad Peterson, and City Theatre’s artistic staff to create this theatrical, multi-camera concert film. -

Partyman by Title

Partyman by Title #1 Crush (SCK) (Musical) Sound Of Music - Garbage - (Musical) Sound Of Music (SF) (I Called Her) Tennessee (PH) (Parody) Unknown (Doo Wop) - Tim Dugger - That Thing (UKN) 007 (Shanty Town) (MRE) Alan Jackson (Who Says) You - Can't Have It All (CB) Desmond Decker & The Aces - Blue Oyster Cult (Don't Fear) The - '03 Bonnie & Clyde (MM) Reaper (DK) Jay-Z & Beyonce - Bon Jovi (You Want To) Make A - '03 Bonnie And Clyde (THM) Memory (THM) Jay-Z Ft. Beyonce Knowles - Bryan Adams (Everything I Do) I - 1 2 3 (TZ) Do It For You (SCK) (Spanish) El Simbolo - Carpenters (They Long To Be) - 1 Thing (THM) Close To You (DK) Amerie - Celine Dion (If There Was) Any - Other Way (SCK) 1, 2 Step (SCK) Cher (This Is) A Song For The - Ciara & Missy Elliott - Lonely (THM) 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) (CB) Clarence 'Frogman' Henry (I - Plain White T's - Don't Know Why) But I Do (MM) 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New (SF) Cutting Crew (I Just) Died In - Coolio - Your Arms (SCK) 1,000 Faces (CB) Dierks Bentley -I Hold On (Ask) - Randy Montana - Dolly Parton- Together You And I - (CB) 1+1 (CB) Elvis Presley (Now & Then) - Beyonce' - There's A Fool Such As I (SF) 10 Days Late (SCK) Elvis Presley (You're So Square) - Third Eye Blind - Baby I Don't Care (SCK) 100 Kilos De Barro (TZ) Gloriana (Kissed You) Good - (Spanish) Enrique Guzman - Night (PH) 100 Years (THM) Human League (Keep Feeling) - Five For Fighting - Fascination (SCK) 100% Pure Love (NT) Johnny Cash (Ghost) Riders In - The Sky (SCK) Crystal Waters - K.D. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

4BH 1000 Best Songs 2011 Prez Final

The 882 4BH1000BestSongsOfAlltimeCountdown(2011) Number Title Artist 1000 TakeALetterMaria RBGreaves 999 It'sMyParty LesleyGore 998 I'llNeverFallInLoveAgain BobbieGentry 997 HeavenKnows RickPrice 996 ISayALittlePrayer ArethaFranklin 995 IWannaWakeUpWithYou BorisGardiner 994 NiceToBeWithYou Gallery 993 Pasadena JohnPaulYoung 992 IfIWereACarpenter FourTops 991 CouldYouEverLoveMeAgain Gary&Dave 990 Classic AdrianGurvitz 989 ICanDreamAboutYou DanHartman 988 DifferentDrum StonePoneys/LindaRonstadt 987 ItNeverRainsInSouthernCalifornia AlbertHammond 986 Moviestar Harpo 985 BornToTry DeltaGoodrem 984 Rockin'Robin Henchmen 983 IJustWantToBeYourEverything AndyGibb 982 SpiritInTheSky NormanGreenbaum 981 WeDoIt R&JStone 980 DriftAway DobieGray 979 OrinocoFlow Enya 978 She'sLikeTheWind PatrickSwayze 977 GimmeLittleSign BrentonWood 976 ForYourEyesOnly SheenaEaston 975 WordsAreNotEnough JonEnglish 974 Perfect FairgroundAttraction 973 I'veNeverBeenToMe Charlene 972 ByeByeLove EverlyBrothers 971 YearOfTheCat AlStewart 970 IfICan'tHaveYou YvonneElliman 969 KnockOnWood AmiiStewart 968 Don'tPullYourLove Hamilton,JoeFrank&Reynolds 967 You'veGotYourTroubles Fortunes 966 Romeo'sTune SteveForbert 965 Blowin'InTheWind PeterPaul&Mary 964 Zoom FatLarry'sBand 963 TheTwist ChubbyChecker 962 KissYouAllOver Exile 961 MiracleOfLove Eurythmics 960 SongForGuy EltonJohn 959 LilyWasHere DavidAStewart/CandyDulfer 958 HoldMeClose DavidEssex 957 LadyWhat'sYourName Swanee 956 ForeverAutumn JustinHayward 955 LottaLove NicoletteLarson 954 Celebration Kool&TheGang 953 UpWhereWeBelong -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

Country Airplay; Brooks and Shelton ‘Dive’ In

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS JUNE 24, 2019 | PAGE 1 OF 19 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Thomas Rhett’s Behind-The-Scenes Country Songwriters “Look” Cooks >page 4 Embracing Front-Of-Stage Artist Opportunities Midland’s “Lonely” Shoutout When Brett James sings “I Hold On” on the new Music City Puxico in 2017 and is working on an Elektra album as a member >page 9 Hit-Makers EP Songs & Symphony, there’s a ring of what-ifs of The Highwomen, featuring bandmates Maren Morris, about it. Brandi Carlile and Amanda Shires. Nominated for the Country Music Association’s song of Indeed, among the list of writers who have issued recent the year in 2014, “I Hold On” gets a new treatment in the projects are Liz Rose (“Cry Pretty”), Heather Morgan (“Love Tanya Tucker’s recording with lush orchestration atop its throbbing guitar- Someone”), and Jeff Hyde (“Some of It,” “We Were”), who Street Cred based arrangement. put out Norman >page 10 James sings it with Rockwell World an appropriate in 2018. gospel-/soul-tinged Others who tone. Had a few have enhanced Marty Party breaks happened their careers with In The Hall differently, one a lbu ms i nclude >page 10 could envision an f o r m e r L y r i c alternate world in Street artist Sarah JAMES HUMMON which James, rather HEMBY Buxton ( “ S u n Makin’ Tracks: than co-writer Daze”), who has Riley Green’s Dierks Bentley, was the singer who made “I Hold On” a hit. done some recording with fellow songwriters and musicians Sophomore Single James actually has recorded an entire album that’s expected under the band name Skyline Motel; Lori McKenna (“Humble >page 14 later this year, making him part of a wave of writers who are and Kind”), who counts a series of albums along with her stepping into the spotlight with their own multisong projects. -

If There's a Pedigree for a Modern Country Music Star, Then Angaleena

If there’s a pedigree for a modern country music star, then Angaleena Presley fits all of the criteria: a coal miner’s daughter; native of Beauty, Kentucky; a direct descendent of the original feuding McCoys; a one-time single mother; a graduate of both the school of hard knocks and college; a former cashier at both Wal-Mart and Winn-Dixie. Perhaps best of all the member of Platinum-selling Pistol Annies (with Miranda Lambert and Ashley Monroe) says she “doesn’t know how to not tell the truth.” That truth shines through on her much-anticipated debut album, American Middle Class, which she co-produced with Jordan Powell. Yet this is not only the kind of truth that country music has always been known for—American Middle Class takes it a step further by not only being a revealing memoir of Presley’s colorful experiences but also a powerful look at contemporary rural American life. “I have lived every minute on this record. My mama ain’t none too happy about me spreading my business around but I have to do it,” Presley says. “It’s the experience of my life from birth to now.” Yet the specificity of the album’s twelve gems only makes it more universal. While zooming in on the details of her own life, Presley exposes themes to which everyone can relate. The album explores everything from a terrible economy to unexpected pregnancies to drug abuse in tightly written songs that transcend the specific and become tales of our shared experiences. “I think a good song is one where people listen to a very personal story and think ‘That’s my story, too,’” Presley says. -

Ode to Billie Joe

Ode to Billie Joe (2016) Wenn ich renoviere, habe ich gerne Musik dabei. Dann kommt der alte Ghettoblaster zum Einsatz, den ich vor Jahren unterm Sperrmüll im Keller gefunden habe. Das CD- Laufwerk geht nicht mehr, aber das für Kassetten tut es noch, und das genügt. CDs habe ich nur wenige, dafür umso mehr von den alten MCs, bespielt in den 1970ern und 1980ern, zigmal in meinem Autoradio gelaufen während der Fahrten zwischen Hamburg und München und während anderer Reisen. Entsprechend die Tonqualität, die Kassetten sind alt und abgelatscht, aber zur Unterhaltung, während ich auf der Leiter stehe, reichen sie aus. Mehrere Kassetten tragen die Aufschrift „Oldies“, das sind mir beim Renovieren die liebsten. Eine oder die andere enthält Material, das noch von meinem alten Tonbandgerät stammt, Aufnahmen aus dem Radio oder von Schallplatten, die ich mir in den 1960ern kaufte, 45er-Singles von Stücken, die mir damals besonderen Eindruck machten. Nun renoviere ich nicht besonders oft, deswegen hatte ich nur selten Gelegenheit, die alten Nummern wiederzuhören. 2008 war wohl das letzte Mal gewesen, davor vielleicht 1994, in solchen Abständen geht das bei mir. In diesem Jahr 2016 musste ich jedoch wieder ran, außer der Reihe, nicht in meinen Zimmern, sondern in dem dritten, dem großen, in dem Untermieter Michel fast zehn Jahre gehaust hatte. Das war bös heruntergekommen, es gab viel zu tun, der Ghettoblaster musste tagelang das Zimmer vollschallen. Die „Oldies“-Kassetten liefen mehrmals, ich hatte mein Vergnügen an den alten Hits wie „Bend Me, Shake Me“, „Hush“, „Johnny Reggae“ und „Jeans On“, an den Songs von Jefferson Airplane, den Animals und Steppenwolf. -

Karaoke Version Song Book

Karaoke Version Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID (Hed) Planet Earth 50 Cent Blackout KVD-29484 In Da Club KVD-12410 Other Side KVD-29955 A Fine Frenzy £1 Fish Man Almost Lover KVD-19809 One Pound Fish KVD-42513 Ashes And Wine KVD-44399 10000 Maniacs Near To You KVD-38544 Because The Night KVD-11395 A$AP Rocky & Skrillex & Birdy Nam Nam (Duet) 10CC Wild For The Night (Explicit) KVD-43188 I'm Not In Love KVD-13798 Wild For The Night (Explicit) (R) KVD-43188 Things We Do For Love KVD-31793 AaRON 1930s Standards U-Turn (Lili) KVD-13097 Santa Claus Is Coming To Town KVD-41041 Aaron Goodvin 1940s Standards Lonely Drum KVD-53640 I'll Be Home For Christmas KVD-26862 Aaron Lewis Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow KVD-26867 That Ain't Country KVD-51936 Old Lamplighter KVD-32784 Aaron Watson 1950's Standard Outta Style KVD-55022 An Affair To Remember KVD-34148 That Look KVD-50535 1950s Standards ABBA Crawdad Song KVD-25657 Gimme Gimme Gimme KVD-09159 It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas KVD-24881 My Love, My Life KVD-39233 1950s Standards (Male) One Man, One Woman KVD-39228 I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus KVD-29934 Under Attack KVD-20693 1960s Standard (Female) Way Old Friends Do KVD-32498 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31474 When All Is Said And Done KVD-30097 1960s Standard (Male) When I Kissed The Teacher KVD-17525 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31475 ABBA (Duet) 1970s Standards He Is Your Brother KVD-20508 After You've Gone KVD-27684 ABC 2Pac & Digital Underground When Smokey Sings KVD-27958 I Get Around KVD-29046 AC-DC 2Pac & Dr. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS MARCH 9, 2020 | PAGE 1 OF 17 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Morris, Brown Top Charts Brandy Clark Makes A Personal >page 4 Statement On The Record Nashville Works Toward Recovery Ten seconds into Brandy Clark’s Your Life Is a Record, a the listener to an expectant conclusion of what turns out to be >page 9 languid grunting tone emerges, unconventionally planting a breakup album, released by Warner on March 6. “The Past a baritone sax into the opening moments of what’s ostensibly Is the Past,” she declares in that glassy finale, with fragile a country album. guitar arpeggios supporting a It’s a tad mysterious. In transitional journey into some Dan + Shay Launch context, it could be a bassoon or unknown future. Putting that Arena Tour a bass clarinet — Clark thought upbeat sentiment at the end >page 10 it was a cello the first time she of the project rather than the heard it — but it reveals to the beginning was one of the few listener that Your Life Is a Record, places where she dug in her heels produced by Jay Joyce (Eric with the label. Current News: Church, Miranda Lambert), “I wanted it that way because Just LeDoux It is not quite like either of the to me, ‘The Past Is the Past’ is >page 10 previous records the award- bittersweet, but it’s hopeful,” winning singer-songwriter has she explains. “It’s like, ‘OK, we’ve launched in the marketplace. gone through all this and I’m still Makin’ Tracks: “I said to Jay when I heard sad about it, but I’m letting you Pardi’s Strait Talk that baritone sax thing, ‘Man, go.’ And I’m driving away — like, >page 14 I know this is crazy ’cause it’s a I literally feel like I’m in the car slow, sad song. -

MUJER Y MÚSICA, 144 Discos Que Avalan Esta Relación Relación

MUJER Y MÚSICA, 144 discos que avalan esta relación Toni Castarnado Tras una extensa conversación con la musa Patti Smith, el autor se sumerge en la historia de la música protagonizada por mujeres solistas de todos los estilos . Viajando a l os inicios de la música popular, llega hasta la actualidad, Castar nado retrata la mejor cosecha femenina y las circunstancias que la rodearon. Blues, jazz, rock, country, folk, soul o hip hop... el autor viaja duran te décadas radiografiando a sus protagonistas y apuntando las obras capitales que no pueden faltar en toda buena discoteca que se precie de serlo. CO NTENIDO: Brandi Carlile Prólogo por Rickie Lee Eleni Mandell Julee Cruise Brenda Kahn Jones Ella Fitzgerald June Carter Cash Introducción con Patti Candi Staton Emmylou Harris K.D. Lang Carla Thomas Karen Dalton Smith Erin McKeown Carmen Consoli Abbey Lincoln Erykah Badu Kasey Chambers Kate Bush Aimee Mann Carole King Etta James Katie Melua Alani s Morissette Cass Elliot Ethel Waters Cassandra Wilson Feist Alison Krauss Koko Taylor Cat Power Amy Winehouse Fiona Apple Kristin Hersh Cecilia Anari Frida Hyvönen La Lupe Ani Difranco Cheralee Dillon Gillian Welch Laura Nyro Anita Lane Christina Rosenvinge Holly Golightly Laura Veirs Anita O8Day Cyndi Lauper Imelda May Lauren Hoffman Irma Thomas Ann Peebles Danya Kurtz Laurie Anderson Annie Ross Dee Dee Bridgewater Jane Birkin Lauryn Hill Lhasa Aretha Franklin Diana Ross Janis Joplin Astrud Gilberto Dianne Reeves Jesse Sykes & The Linda Ronstadt Bessie Smith Dinah Washington Sweet Hereafter Lisa