Enhancing Police and Industry Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commencement 2006-2011

2009 OMMENCEMENT / Conferring of Degrees at the Close of the 1 33rd Academic Year Johns Hopkins University May 21, 2009 9:15 a.m. Contents Order of Procession 1 Order of Events 2 Divisional Ceremonies Information 6 Johns Hopkins Society of Scholars 7 Honorary Degree Citations 12 Academic Regalia 15 Awards 17 Honor Societies 25 Student Honors 28 Candidates for Degrees 33 Please note that while all degrees are conferred, only doctoral graduates process across the stage. Though taking photos from vour seats during the ceremony is not prohibited, we request that guests respect each other's comfort and enjoyment by not standing and blocking other people's views. Photos ol graduates can he purchased from 1 lomcwood Imaging and Photographic Services (410-516-5332, [email protected]). videotapes and I )\ I )s can he purchased from Northeast Photo Network (410 789-6001 ). /!(• appreciate your cooperation! Graduates Seating c 3 / Homewood Field A/ Order of Seating Facing Stage (Left) Order of Seating Facing Stage (Right) Doctors of Philosophy and Doctors of Medicine - Medicine Doctors of Philosophy - Arts & Sciences Doctors of Philosophy - Advanced International Studies Doctors of Philosophy - Engineering Doctors of Philosophy, Doctors of Public Health, and Doctors of Masters and Certificates -Arts & Sciences Science - Public Health Masters and Certificates - Engineering Doctors of Philosophy - Nursing Bachelors - Engineering Doctors of Musical Arts and Artist Diplomas - Peabody Bachelors - Arts & Sciences Doctors of Education - Education Masters -

Internet Freedom in China: U.S. Government Activity, Private Sector Initiatives, and Issues of Congressional Interest

Internet Freedom in China: U.S. Government Activity, Private Sector Initiatives, and Issues of Congressional Interest Patricia Moloney Figliola Specialist in Internet and Telecommunications Policy May 18, 2018 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R45200 Internet Freedom in China: U.S. Government and Private Sector Activity Summary By the end of 2017, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) had the world’s largest number of internet users, estimated at over 750 million people. At the same time, the country has one of the most sophisticated and aggressive internet censorship and control regimes in the world. PRC officials have argued that internet controls are necessary for social stability, and intended to protect and strengthen Chinese culture. However, in its 2017 Annual Report, Reporters Without Borders (Reporters Sans Frontières, RSF) called China the “world’s biggest prison for journalists” and warned that the country “continues to improve its arsenal of measures for persecuting journalists and bloggers.” China ranks 176th out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2017 World Press Freedom Index, surpassed only by Turkmenistan, Eritrea, and North Korea in the lack of press freedom. At the end of 2017, RSF asserted that China was holding 52 journalists and bloggers in prison. The PRC government employs a variety of methods to control online content and expression, including website blocking and keyword filtering; regulating and monitoring internet service providers; censoring social media; and arresting “cyber dissidents” and bloggers who broach sensitive social or political issues. The government also monitors the popular mobile app WeChat. WeChat began as a secure messaging app, similar to WhatsApp, but it is now used for much more than just messaging and calling, such as mobile payments, and all the data shared through the app is also shared with the Chinese government. -

Corona-Fastnet-Short-Film-Festival

FASTNET SHORT FILM FESTIVAL OUR VILLAGE IS OUR SCREEN stEErIng coMMIttEE fEstIvAL pAtrons 2012 welcome to schull and CFSFF 2012! MAurIcE sEEzEr tony bArry thanks to all of our sponsors for sticking with us in 2012, and in Chair & Artistic Director stEvE coogAn particular to our title sponsors Michael and kathleen Barry of Barry hELEn wELLs sInéAd cusAck & Fitzwilliam, importers of Corona, who won an allianz Business Co-Chair, Admin & Submissions grEg dykE to arts award for their cheerful and encouraging sponsorship of MArIA pIzzutI JAck goLd CFSFF in 2011. these last years have been enormously stressful Co-Artistic Director JErEMy Irons to festivals around the country as government funding for the arts hILAry McCarthy John kELLEhEr in Ireland dries up, and just when it seemed like it couldn’t get any Public Relations Officer chrIs o’dELL bsc worse, there is a whisper that the sponsorship support that alcohol PauLInE cottEr DavId puttnAM brands give to both arts festivals and sporting events around Ireland Fundraising JIM shErIdAn may be banned by the government within the next two years. If this brIdIE d’ALton kIrstEn shErIdAn goes ahead, it will accelerate the centralization of cultural events Treasurer gErArd stEMbrIdgE in larger population centres already well under way thanks to the economic recession and will consequently put huge pressure on tEchnIcAL dIrEctor for ALL EnquIrIEs all festivals in rural areas, including our own. this will have an MArtIn LEvIs pLEAsE contAct: extremely negative impact on an already under pressure tourism sector and is surely unnecessary at this time. grAphIc dEsIgn FEStIval Box oFFICE JonAthAn pArson @ Your lEISurE last year we developed Distributed Cinema and became a mutegrab.com MaIn StrEEt streaming festival for the short film competition submitters, all PAUL GOODE SChull within the confines of Main Street Schull. -

Rally Guide – NASA Rally Sport IS Grassroots!

Rally Guide – NASA Rally Sport IS Grassroots! Rally Guide March 5 – 7, 2015 2015 NASA National Rally Championship 2015 Atlantic Rally Cup 2015 Atlantic RallyMoto™ Cup 11 Introduction This document has no regulatory power and is to be used for information only. Sections 1 through 21 and the appendices conform to FIA WRC Appendix 3 regulations for Rally Guides. 1.1 Welcome Message from the Chairman Hello, everyone! Thanks for making the trip to South Carolina for Sandblast Rally! There has never been a better time for racing in South Carolina! New competitors have joined the sport for the 2015 racing season and our volunteer base is filled with new people and great ideas. For a couple years now Sandblast Rally has the largest entry count in the country! This year's schedule includes the fun roads that you know and love with the return of the new timing system equipment – the NASA Rally Sport Nook clocks and online scoring system will be used at the rally this year. Despite lengthening days in early spring, teams should be prepared to run our sandy stages at night, too! Traditionally, Sandblast Rally has served the club-man level competitor and this is still our philosophy. It remains the most affordable event on the East Coast with Jemba stage notes! Our documentation is top-notch and we encourage you to read the Rally Guide for all the local need-to-know details. Our volunteers are friendly – many come from the local communities. Feel free to ask questions as you prepare for the event and arrive in South Carolina. -

Coen Trophy (Mixed Teams Championship)

CBAI National Presidents Duais An Uachtarain (President’s Prize) Spiro Cup (Mixed Pairs Championship) Coen Trophy (Mixed Teams Championship) Master Pairs (National Open Pairs) Holmes Wilson Cup (National Open Teams) Revington Cup (Men’s Pairs) Jackson Cup (Women’s Pairs) Geraldine Trophy (Men’s Teams) McMenamin Bowl (Women’s Teams) Lambert Cup (National Confined Pairs) Cooper Cup (National Confined Teams) Davidson Cup (National Open Pairs) Laird Cup (National Intermediate A Pairs) Civil Service Cup (National Intermediate B Pairs) Kelburne Cup (National Open Teams) Bankers Trophy (National Intermediate A Teams) Tierney Trophy (National Intermediate B Teams) Home International Series Burke Trophy (IBU Inter-County Teams) O’Connor Trophy (IBU Inter-County Intermediate Teams) Frank & Brenda Kelly Trophy (Inter-County 4Fun Teams) Novice & Intermediate Congress JJ Murphy Trophy (National Novice Pairs) IBU Club Pairs Egan Trophy (IBU All-Ireland Teams) Moylan Cup (IBU All-Ireland Pairs) IBU Seniors’ Congress CBAI National Presidents 2019 Neil Burke 2016 Pat Duff 2017 Jim O’Sullivan 2018 Peter O’Meara 2013 Thomas MacCormac 2014 Fearghal O’Boyle 2015 Mrs Freda Fitzgerald 2010 Mrs Katherine Lennon 2011 Mrs Sheila Gallagher 2012 Liam Hanratty 2007 Mrs Phil Murphy 2008 Martin Hayes 2009 Mrs Mary Kelly-Rogers 2004 Mrs Aileen Timoney 2005 Paddy Carr 2006 Mrs Doreen McInerney 2001 Seamus Dowling 2002 Mrs Teresa McGrath 2003 Mrs Rita McNamara 1998 Peter Flynn 1999 Mrs Kay Molloy 2000 Michael O’Connor 1995 Denis Dillion 1996 Mrs Maisie Cooper 1997 Mrs -

Storytelling and Craft Videos Posted by Dublin City Libraries Staff from October 2020 Authority Name: Dublin City Libraries

Storytelling and craft videos posted by Dublin City Libraries staff from October 2020 Authority Name: Dublin City Libraries Video Link Title Library Author Illustrator Publisher Age Range https://www.facebook.com/CabraLibrary/videos/798463010696348 Fionn and the Baby (from Best-Loved Irish Legends)Cabra Library Eithne Massey Lisa Jackson O'Brien Press ages 5- 8 October '20 https://www.facebook.com/MarinoLibrary/videos/348102706516320/ Danny's Smelly Toothbrush Marino Library Brianóg Brady Dawson Michael Connor O'Brien Press ages 4 - 7 October '20 https://www.facebook.com/CabraLibrary/videos/280224509717108/ Let's See Ireland Cabra Library Sarah Bowie O'Brien Press ages 3 - 6 October '20 https://www.facebook.com/CabraLibrary/videos/3401529443280226/ The President's Surprise Cabra Library Peter Donnelly Gill Books ages 3 - 6 October '20 https://www.facebook.com/MarinoLibrary/videos/3525948904115345/ Emma Says Boo! Marino Library Anna Donovan Woody Fox O'Brien Press ages 3 - 6 October '20 https://www.facebook.com/phibsborolibrary/videos/1836187506546768/ A Dublin Fairytale Phibsboro Library Nicola Colton O'Brien Press ages 3 - 6 October '20 https://www.facebook.com/CabraLibrary/videos/2723542954536291/ Lúlú agus an Oíche Ghlórach Cabra Library Bridget Breathnach Steve Simpson Futa Fata ages 3 - 6 October '20 https://www.facebook.com/CabraLibrary/videos/1058534631252537/ The President's Cat Cabra Library Peter Donnelly O'Brien Press ages 3 - 6 October '20 https://www.facebook.com/CoolockLibrary/videos/5168490036498053/ A Dublin Fairytale -

Freedom on the Net 2016

FREEDOM ON THE NET 2016 China 2015 2016 Population: 1.371 billion Not Not Internet Freedom Status Internet Penetration 2015 (ITU): 50 percent Free Free Social Media/ICT Apps Blocked: Yes Obstacles to Access (0-25) 18 18 Political/Social Content Blocked: Yes Limits on Content (0-35) 30 30 Bloggers/ICT Users Arrested: Yes Violations of User Rights (0-40) 40 40 TOTAL* (0-100) 88 88 Press Freedom 2016 Status: Not Free * 0=most free, 100=least free Key Developments: June 2015 – May 2016 • A draft cybersecurity law could step up requirements for internet companies to store data in China, censor information, and shut down services for security reasons, under the aus- pices of the Cyberspace Administration of China (see Legal Environment). • An antiterrorism law passed in December 2015 requires technology companies to cooperate with authorities to decrypt data, and introduced content restrictions that could suppress legitimate speech (see Content Removal and Surveillance, Privacy, and Anonymity). • A criminal law amendment effective since November 2015 introduced penalties of up to seven years in prison for posting misinformation on social media (see Legal Environment). • Real-name registration requirements were tightened for internet users, with unregistered mobile phone accounts closed in September 2015, and app providers instructed to regis- ter and store user data in 2016 (see Surveillance, Privacy, and Anonymity). • Websites operated by the South China Morning Post, The Economist and Time magazine were among those newly blocked for reporting perceived as critical of President Xi Jin- ping (see Blocking and Filtering). www.freedomonthenet.org FREEDOM CHINA ON THE NET 2016 Introduction China was the world’s worst abuser of internet freedom in the 2016 Freedom on the Net survey for the second consecutive year. -

The Internet: a New Tool for Law Enforcement Todd Kirchgraber

The Internet: A New Tool for Law Enforcement Todd Kirchgraber Abstract In the past five years personal computers and the Internet have revolutionized how people are now obtaining information they feel is important in their daily lives. With this “on-line” information explosion comes the ability for law enforcement world wide to share information with citizens, local communities and other police agencies. As this ability grows, are law enforcement agencies taking advantage of all that the Internet has to offer? Is this a useful technology or just a passing fad? This research paper will help to identify which law enforcement agencies in the state of Florida are using the Internet to post web sites as well as their perceived benefits (if any), and the agencies’ goal in developing these sites. Introduction On June 21, 1998, a search of the Internet on the single keyword “police” using the INFOseek sm. search engine located 1,126,036 pages relating to that topic. A similar search conducted on June 16, 1998 within the WebLUIS library system on the key words “Police and Internet” produced only 44 citations prior to 1988 and listed 5000 citations from 1988 to 1998. These numbers alone indicate more and more criminal justice and law enforcement agencies are using this technology to some degree. But how effective is it? With more than 40 million users, the World Wide Web offers boundless opportunities. It reaches a limitless audience, providing users with interactive technology and vast resources. No other medium can achieve this as easily or inexpensively (Clayton, 1997). Today, more and more people are getting online. -

Carla Mcglynn

Carla McGlynn Email: mcglynn.carla @gmail.com Equity Number:1320205 Playing Age: 17- 27 Hair Colour: Brunette Height/ Frame: 5”6/ Slim Eye Colour: Blue/ Green Film: King of the Travellers Winnie Power Mark O'Connor Vico Films The Disturbed Sarah Conor McMahon Guardian Productions Girls Diane Maureen O'Connell Three Hot Whiskeys Zombie Bashers Louise Conor McMahon Tailored Films/ RTE Project HaHa Alison George Kane Green Inc/RTE Orpheus Alecto Frankie Shine IADT Shattered Summer Stephen Fuller UCD Begrudgery Molly Dustin Morrow Little Swan Media Agoraphobia Mary Karl Collins DKIT Aidan Is Missing Ashton Dustin Morrow Little Swan Media Theatre: Spider Anne Anthony Fox Strike Liz Tracy Ryan Candy Flipping Butterflies Crumie Shane Gately Spartacus Claudia Paul Burke Ariel Elaine Jim Ivers Storytaker Patricia Patrick Bridgeman War of the Roses Siren Paul Burke Troilus and Cressida Cressida Paul Maher Orpheus Descending Sister Temple Mary Moynihan Voice Over: Heartbreak House Lady Utterword, Miriam O'Meara DIT FM Wanderlust Eric Donal Mangan Animation Training: Actors Studio, The Factory, Shimmy Marcus, Kirsten Sheridan, Lance Daly, John Carney May 2007 B.A. Drama (Performance) DIT, Conservatory of Music & Drama. Dialects/Phonetics, Cathal Quinn, AVI Loose Cannon Workshops, Jason Byrne Classical Acting, Classic Stage Ireland, Andy Hinds Acting to Camera, Vinnie Murphy Comedy Improv, Peter Byrne, The Craic Pack Scene study/ Improv, Actor Training Ireland John Dawson Michael Chekhov Technique, Paul Brennan Acting Masterclass, Howard Fine, LA. Sitcom Acting, Greg Edwards, LA. Scene study/ Improv, John Dawson Audition Technique, Amy Lyndon L.A. Commedia dell'Arte Workshops, Corn Exchange, Annie Ryan Method Acting Masterclass, Shelly Mitchell, Filmbase Acting for screen, Vinny Murphy Facial Mask, Rodrigo Rodriguez Performing Shakespeare, Royal Shakespeare Company, Stratford. -

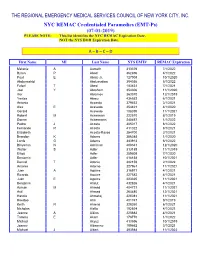

(EMT-Ps) (07-01-2019) PLEASE NOTE: This List Identifies the NYC REMAC Expiration Date, NOT the NYS DOH Expiration Date

THE REGIONAL EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES COUNCIL OF NEW YORK CITY, INC. NYC REMAC Credentialed Paramedics (EMT-Ps) (07-01-2019) PLEASE NOTE: This list identifies the NYC REMAC Expiration Date, NOT the NYS DOH Expiration Date. A – B – C – D First Name MI Last Name NYS EMT# REMAC Expiration Melanie A Aarseth 313376 7/1/2022 Byron P Abad 362896 4/1/2022 Paul E Abate Jr. 127008 10/1/2020 Abdurrashid Abdussalam 384036 5/1/2022 Faisel T Abed 183431 7/1/2021 Joel Y Abraham 354306 11/1/2020 Iller Abramov 363370 12/1/2019 Yaritza Abreu 436552 6/1/2021 Antonio Accardo 379453 3/1/2021 Alex E Acevedo 254421 4/1/2020 Gerard Acevedo 108095 11/1/2021 Robert M Ackerman 222570 8/1/2019 Donna Ackermann 240457 1/1/2022 Pedro J Acosta 305017 6/1/2022 Fernando R Acosta 411022 8/1/2021 Elizabeth Acosta-Rayos 254700 2/1/2021 Brandon K Adams 356348 1/1/2020 Lorris G Adams 343913 6/1/2022 Binyamin N Adelman 408341 12/1/2020 Walter S Adler 313185 11/1/2019 Elliott Adler 259609 7/1/2020 Benjamin Adler 418158 10/1/2021 Denzel T Adonis 382159 2/1/2022 Antonio Adorno 227961 11/1/2021 Juan A Aguirre 316971 4/1/2021 Ricardo Aguirre 227582 4/1/2021 Juan E Aguirre 223325 11/1/2021 Benjamin Ahdut 432826 4/1/2021 Ayman M Ahmad 404721 11/1/2021 Asif Ahmed 264480 12/1/2021 Hasnie Ahmetaj 325081 11/1/2021 Heedoo Ahn 401747 9/1/2019 Keith R Ahrens 228260 6/1/2021 Nicholas Aiello 192624 4/1/2021 Jeanne A Aikins 225683 4/1/2021 Tammy E Akam 178770 1/1/2022 Michael Akyuz 413596 10/1/2019 Joanne Albanese 189662 3/1/2021 Michael J Albert 393984 11/1/2022 THE REGIONAL EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES COUNCIL OF NEW YORK CITY, INC. -

Ansteorran Internal Letter of Intent 2006-05

Ansteorran Internal Letter of Intent 2006-05 1. Áed Vilhiálmsson. (Bryn Gwlad) New Name. New Device. Quarterly Or and argent, in dexter chief a sun in splendor vert. Asterisk Note: A letter of permission to conflict with Maria-Simone de Barjavel ‘la Fildena’s armory “(Fieldless) A compass star of sixteen points argent voided vert ” is included. Major Changes: No. Minor Changes: Yes. Gender: Male. Change for : Meaning: Áed, son of Vilhiálmr (Munster, 850-950). Authenticity: No request Documentation Provided: <Áed> - appears as a masculine personal name in the annals of Ulster, the Four Masters, and Connacht, with dates ranging from 747 to 1594 CE. Documentation taken from “Index of Names in Irish Annals” by Mari Elspeth nic Bryan (http://www.s- gabriel.org/names/mari/AnnalsIndex/Masculine/Aed.shtml and http://www.s- gabriel.org/names/mari/AnnalsIndex/Common/Sources.html) <Vilhiálmr> - appears as a masculine personal name on a runic gravestone in Trondheim, Norway, which has been dated to roughly 1000 CE. Documentation taken from the “Joint Nordic Database for Runic Inscriptions” for the stone’s location and date, and also from the “Nordiskt runnamnlexikon” where on p. 232, s.n. VilhialmR is documentation of its Old West Norse form. Asterisk Note: All photocopies and translations included. 2. Alesone Lesley. (Gate’s Edge) New Name. New Device. Purpure, a cinquefoil ermine, an orle of bees Or. Consultation Table: Gulf Wars Major Changes: No. Minor Changes: Yes. Gender: Female. Change for : Sound: none specified. Authenticity: No request Documentation Provided: <Alesone> - Withycombe, 3rd ed., p. 16, s.n. Alison, has Alisone 1450, 1453. -

Irish Babies Names 2003.Vp

19 May 2004 Irish Babies’ Names Sean and Emma 1998-2003 2003 1000 Sean Five most popular babies’ names 900 Emma Boys Girls 800 700 Name Count Name Count Sean 897 Emma 791 600 Jack 800 Sarah 606 500 Adam 787 Aoife 571 400 Conor 705 Ciara 535 300 James 626 Katie 468 200 100 Sean and Emma 0 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Sean and Emma were the most popular babies’ names registered last year. There were 897 boys named Sean (3.1% of baby boys) and 791 girls named Emma (2.8% of baby girls). See Tables 1 and 2. The top five names for boys remained the same as last year, although the order changed slightly. For girls, Katie replaced Chloe in the top five. See Table 1. There were eight new entries to the top 100 for boys: Cameron, Colin, Daire, Emmanuel, Karl, Max, Reece and Ruairi. The highest new entry was Colin and the highest climber was Kian which rose from 268th place in 1998 to 65th place in 2003. First time entries to the top 100 are Ruairi, Emmanuel and Max. See Table 1. Published by the Central Statistics Office, Ireland. There were nine new names in the top 100 for girls: Alana, Amber, Aoibhe, Ardee Road Skehard Road Dublin 6 Cork Cara, Clara, Faye, Naomi, Sophia and Sorcha. The highest new entry was Clara Ireland Ireland and the highest climber was Abby which rose from 327th place in 1998 to 60th place in 2003. Newcomers to the top 100 are Faye, Naomi, Aoibhe and Sophia.