FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE: Thus Spoke Zarathustra a Book for All and None

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW PRINCIPAL ELECTED to SUCCEED PRESIDENT H. M. DALE Academy Boys Place •••■•••■••

THE CLARION VOL. VI—No. 10 AUGUSTANA ACADEMY, CANTO N, SOUTH DAKOTA, APRIL 1, 1927 PRICE }O.o, NEW PRINCIPAL ELECTED TO SUCCEED PRESIDENT H. M. DALE Academy Boys Place •••■•••■••..... Reverend Rothnem Third at N. L. C. A. New AucustanaAcademy Principal of Dell Rapids New Basketball Tourney Rev. Botolf J. Rothnem, re- Academy Princilwa. Win in the Consolations cently elected principal of To 'fake Up Duties About July 1 Augustana academy to suc- The academy basket ball team left ceed Prof. H. M. Dlae, was a Monday, March 6, to take part in the Rev. Bottolf Jacob Rothnem, 1a,st-or student at St.' Olaf College, N.L.C.A. basketball tournament to of Dell Rapids for more that nine Northfield, Minn., from 1902 years, was unanimously selected. be held at St. Olaf college on March to 1996. He was a member Tuesday by the board of directors of 7, 8, and 9. of the same class as Pres. J. the Augustana College association to They left about eight o'clock Mon- N. Brown of Concordia col- succeed Prof. H. M. Dale as princi- day morning and landed safely in lege and Prof. H. M. Dale. pal of Augustana academy. After Northfield about 9:30 that evening Rev. Rothnem served as accepting th e position, Rev. Rotl,oeira with no trouble to speak of, except president of the Sioux Falls stated that he expects to be ablr t.o stiff joints and limbs. Here they were circuit of the Norwegian enter upon his duties here about taken care Lutheran church of America of and given rooms in the from 1922 to 1924. -

Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation

Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation SCOPE The Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation sector (sector 71) includes a wide range of establish- ments that operate facilities or provide services to meet varied cultural, entertainment, and recre- ational interests of their patrons. This sector comprises (1) establishments that are involved in producing, promoting, or participating in live performances, events, or exhibits intended for pub- lic viewing; (2) establishments that preserve and exhibit objects and sites of historical, cultural, or educational interest; and (3) establishments that operate facilities or provide services that enable patrons to participate in recreational activities or pursue amusement, hobby, and leisure time interests. Some establishments that provide cultural, entertainment, or recreational facilities and services are classified in other sectors. Excluded from this sector are: (1) establishments that provide both accommodations and recreational facilities, such as hunting and fishing camps and resort and casino hotels are classified in Subsector 721, Accommodation; (2) restaurants and night clubs that provide live entertainment, in addition to the sale of food and beverages are classified in Subsec- tor 722, Food Services and Drinking Places; (3) motion picture theaters, libraries and archives, and publishers of newspapers, magazines, books, periodicals, and computer software are classified in Sector 51, Information; and (4) establishments using transportation equipment to provide recre- ational and entertainment services, such as those operating sightseeing buses, dinner cruises, or helicopter rides are classified in Subsector 487, Scenic and Sightseeing Transportation. Data for this sector are shown for establishments of firms subject to federal income tax, and sepa- rately, of firms that are exempt from federal income tax under provisions of the Internal Revenue Code. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

The Tuscan Child

PRAISE FOR RHYS BOWEN’S IN FARLEIGH FIELD “Well-crafted, thoroughly entertaining.” —Publishers Weekly “The skills Bowen brings . inform the plotting in this character-rich tale, which will be welcomed by her fans as well as by readers who enjoy fiction about the British home front.” —Booklist “In what could easily become a PBS show of its own, Bowen’s novel winningly details a World War II spy game.” —Library Journal “This novel will keep readers deeply involved until the end.” —Portland Book Review “In Farleigh Field delivers the same entertainment mixed with intellectual intrigue and realistic setting for which Bowen has earned awards and loyal fans.” —New York Journal of Books “Well-plotted and thoroughly entertaining . With characters who are so fully fleshed out, you can imagine meeting them on the street.” —Historical Novel Society “Through the character’s eyes, readers will be drawn into the era and begin to understand the sacrifices and hardships placed on English society.” —Crimespree Magazine “A thrill a minute . highly recommend.” —Night Owl Reviews, Top Pick “Riveting.” —Military Press “Instantly absorbing, suspenseful, romantic and stylish—like binge- watching a great British drama on Masterpiece Theatre.” —Lee Child, New York Times bestselling author “In Farleigh Field is brilliant. The plotting is razor sharp and ingenious, the setting in World War Two Britain is so tangible it’s eerie. The depth and breadth of character is astonishing. They’re likeable and repulsive and warm and stand-offish. And oh, so human. And so relatable. This is magnificently written and a must read.” —Louise Penny, New York Times bestselling author “Irresistible, charming and heartbreakingly authentic. -

Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment CURRENT ISSUES in ISLAM

Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment CURRENT ISSUES IN ISLAM Editiorial Board Baderin, Mashood, SOAS, University of London Fadil, Nadia, KU Leuven Goddeeris, Idesbald, KU Leuven Hashemi, Nader, University of Denver Leman, Johan, GCIS, emeritus, KU Leuven Nicaise, Ides, KU Leuven Pang, Ching Lin, University of Antwerp and KU Leuven Platti, Emilio, emeritus, KU Leuven Tayob, Abdulkader, University of Cape Town Stallaert, Christiane, University of Antwerp and KU Leuven Toğuşlu, Erkan, GCIS, KU Leuven Zemni, Sami, Universiteit Gent Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment Settling into Mainstream Culture in the 21st Century Benjamin Nickl Leuven University Press Published with the support of the Popular Culture Association of Australia and New Zealand University of Sydney and KU Leuven Fund for Fair Open Access Published in 2020 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). © Benjamin Nickl, 2020 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Non-Derivative 4.0 Licence. The licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non- commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: B. Nickl. 2019. Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment: Settling into Mainstream Culture in the 21st Century. Leuven, Leuven University Press. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Further details about Creative Commons licences -

Song Lyrics of the 1950S

Song Lyrics of the 1950s 1951 C’mon a my house by Rosemary Clooney Because of you by Tony Bennett Come on-a my house my house, I’m gonna give Because of you you candy Because of you, Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give a There's a song in my heart. you Apple a plum and apricot-a too eh Because of you, Come on-a my house, my house a come on My romance had its start. Come on-a my house, my house a come on Come on-a my house, my house I’m gonna give a Because of you, you The sun will shine. Figs and dates and grapes and cakes eh The moon and stars will say you're Come on-a my house, my house a come on mine, Come on-a my house, my house a come on Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give Forever and never to part. you candy Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give I only live for your love and your kiss. you everything It's paradise to be near you like this. Because of you, (instrumental interlude) My life is now worthwhile, And I can smile, Come on-a my house my house, I’m gonna give you Christmas tree Because of you. Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give you Because of you, Marriage ring and a pomegranate too ah There's a song in my heart. -

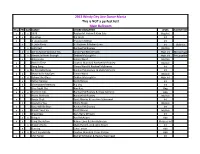

Main Ballroom Playlist

2013 Windy City Line Dance Mania This is NOT a perfect list! Main Ballroom Thur FRI SAT DANCE CHOREOGRAPHER LEVEL TAUGHT BY x x x 1929 Robbie M. Hickie & Kate Sala Beg/Int x x 50 Ways Pat Stott Int x A Liquid Lunch Francien Sittrop Int x A Little Party Jill Babinec & Ruben Luna Int Babinec x Addicted Rachael McEnaney Int/Adv x x Ain't Leaving Without You Linda Paul McCormack High Int McCormack x Almost Is Never Enough Debbie McLaughlin High Int McLaughlin x Americano Simon Ward Int/Adv x Back In Time Guyton Mundy & Rachael McEnaney Int/Adv x Bang Bang Simon Ward & Rachael McEnaney Int x Be My Baby Now Rachael McEnaney & Vicky St Pierre Int x x Beautiful In My Eyes Simon Ward Int/Adv x x Behind the Glass Debbie McLaughlin High Int x Better Believe Scott Blevins Int x Bittersweet Memory Ria Vos Int x Blue Night Cha Kim Ray Beg x x x Blurred Lines Rachael McEnaney & Arjay Centeno Adv x Boom Sh-Boom Rachael McEnaney Int/Adv x Booty Chuk Scott Blevins & Lou Ann Schemmel Int x Bound to You Maria Maag Int/Adv x Boys Will Be Boys Rachael McEnaney Int x x Break Free Cha Scott Blevins Int/Adv x x Breathless Karl-Harry Winson Int x x Bring It Paul McAdam Adv x x Bring the Action Ruben Luna & John Robinson Phrased Int x Broken Heels Mark Furnell, Jo & John Kinser Int x Burning Cato Larson Adv x x Can't Handel Me Guyton Mundy & Carey Parson Adv x Chill Factor Daniel Whitaker & Hayley Westhead Int x x x Clap Happy! Shaz Walton Int x x x Clap Your Hands Joey Warren High Int x x x Come Together 2013 Debbie McLaughlin Adv x Coolio Rachael McEnaney & Arjay -

ENGL 864* Topics in Modernism IV: Modernism in Literature, Arts, and Entertainment

ENGL 864* Topics in Modernism IV: Modernism in Literature, Arts, and Entertainment This is a draft syllabus. While texts are unlikely to be added, I am still working on whittling down the readings to an optimum amount per week, so a couple here or there may be subtracted or designated optional. This course will take us on a whirlwind tour across the jagged landscapes of modernist innovation, both avant-garde and popular—taking in literary fiction, poetry, drama, pulp genres (crime, horror, science fiction), comic strips and books, visual arts and architecture, music and dance. Our starting point will be current debates about the scope and meaning of the term modernism, followed by an exploration of its diverse formal experiments and social and intellectual concerns in the first half of the twentieth century. Evaluation is based on weekly micro-analyses, a seminar presentation, a research prospectus (ungraded) and a research paper. Schedule 1. Introduction, Part 1: Music (What Is Modernism?) Criticism: Ross, The Rest is Noise 36-49, 60-66, 80-85, 130-170 Art: Listening to: Schoenberg, Stravinsky, Debussy Listening to: Jelly Roll Morton, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday 2. Introduction, Part II: Dance (What Is Modernism?) Criticism: Childs, Modernism Introduction and ch. 1 Friedman, “Definitional Excursions” Rohman, “Nude Vibrations” McBreen, “Gender Bending in Harlem” (on Nugent’s Salomé series) Art: Viewing: Graham, Heretic (4m); Baker, Siren of the Tropics (excerpt); Ellington, Symphony in Black (10m); Nazimova, Salomé (74m) Yeats, “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen” 3. Fine Arts (What Is Modernism’s Object of Representation?) Criticism: Childs, Modernism ch. -

Hip Hop, Memes, and the Internet

BY ALL MEMES NECESSARY: HIP HOP, MEMES, AND THE INTERNET MAX TRETTER FRIEDRICH-ALEXANDER-UNIVERSITY ERLANGEN-NUREMBERG INTRODUCTION: HIP HOP ON THE INTERNET The internet influences hip hop in various ways. First and foremost, the internet is a medium that opens up a new space and stage in which hip hop can be performed. This stage is no longer local, but global, which represents both opportunity and challenge. On the one hand, each hip hop artist must assert themselves against countless compet- itors from all over the world; on the other hand, their breakthrough online, if it suc- ceeds, can be monumental in comparison to an analog breakthrough, which is usually confined to a limited area. Therefore, for hip hop artists it is increasingly important to attract attention – as only those who get the attention succeed in this new medium (Prior 2018, Jenkins et al. 2013). The internet’s central influence on hip hop is the inten- sification of the battle for attention – which results in hip hop artists trying new ap- proaches and strategies to gain that attention. One of them is producing their content with an eye to making it as meme-able as possible and capitalizing on meme dynamics on the internet. In this study, I approach memes as a concept, following the definition of Dawkins (2006) who originally defined the concept of memes in his work The Selfish Gene. Memes are small units of information that are usually very simple and catchy (ges- tures, styles, melodies, or phrases). They are transmitted from person to person by imitation or adaption, replicate and spread very quickly, and contribute to the dissem- ination and formation of common behaviors and cultures (Dawkins 2006). -

Module-9 Background Prose Readings COMEDY and TRAGEDY

Module-9 Background Prose Readings COMEDY AND TRAGEDY What is comedy? The word ‘Comedy’ has been derived the French word comdie, which in turn is taken from the Greeco-Latin word Comedia. The word comedia is made of two words komos, which means revel and aeidein means to sing. According to Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, comedy means a branch of drama, which deals with everyday life and humourous events. It also means a play of light and amusing type of theatre. Comedy may be defined as a play with a happy ending. Function of Comedy Though, there are many functions of comedy, yet the most important and visible function of comedy is to provide entertainment to the readers. The reader is forced to laugh at the follies of various characters in the comedy. Thus, he feels jubilant and forgets the humdrum life. George Meredith, in his Idea of Comedy, is of the view that comedy appeals to the intelligence unadulterated and unassuming, and targets our heads. In other words, comedy is an artificial play and its main function is to focus attention on what ails the world. Comedy is critical, but in its scourge of folly and vice. There is no contempt or anger in a comedy. He is also of the view that the laughter of a comedy is impersonal, polite and very near to a smile. Comedy exposes and ridicules stupidity and immorality, but without the wrath of the reformer. Kinds of Comedy 1. Classical Comedy Classical comedy is a kind of comedy, wherein the author follows the classical rules of ancient Greek and Roman writers. -

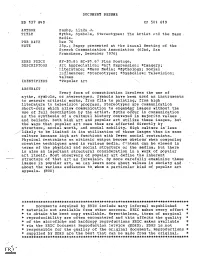

Art Expression; *Imagery; Myths, Symbols, Or Stereotypes. Symbols Have Been Used As Instruments Literature To

DOCUEENT RESUME ED 137 840 CS 501 619 AUTHOR. Busby, Linda J. -TITLE Myths, Symbols, Stereotypes: The ArtiSt end the Mass Media. PUB DATE Dec 76 NOTE 25p.; .Paper presented.at the Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association (62nd, San Francisco, December 1976) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$1,67 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Art Apprecation; *Art Expression; *Imagery; literature; *Mass Media; *Mythology; Social Influences; *Stereotypes; *Symbolism; Television; Values IDENTIFIERS *Popular Art ABSTRACT Every form of communication involves the use Of . myths, symbols, or stereotypes. Symbols have been used as instruments to measure artistic works-, from film to painting, from high literature to television'programs. Stereotypes are communication short-Cuts which allow communication to engert*T images without.the use of full description by the atist. Myths oedur in communication as the synthesis of a cultural history conveyed in majoritv:valnes and beliefs. Both high art and popular art utilize these images, but the ways that popular art uses them are affected direCtly by structure, social worth, and social mobility. High culture is'less to be limited in its utilization of .these images than is mass . culture because high art functions with fewer social restraints. Physical restraints on artistic output become obvious'when comparing creative techniques used in various media. Content can be viewed in terms of the physical and Social structure oi the medium, but there is also an important structural consideration in a work of popular . art itself. Most observers of popular art define the inherent structure of that art as formulaic. By more carefully examining these images in popular art, we can learn more about values in sbciety and, - about the various audiences to:whom a particular kind of popular art appeals. -

Introduction M Priorities

Mose_0771065043_xp_01_r1.qxd 9/25/06 3:40 PM Page 1 We Contain Multitudes: Our Many Roles, Many Selves introduction anager, professional, mentor, mother, wife, volunteer, artist, friend, athlete. Never before M have there been so many demands on women to excel in so many domains of life, so many opportuni- ties for self-expression and success, for disappointment and frustration. Our sense of self is nuanced, intricate, and rich. We derive our feelings of satisfaction from multi- ple roles. Freud famously said: “Love and work are the corner- stone of our humanness.” If we augment “love” to include our friends and our passions and “work” to include paid and unpaid activity, this is all that matters. These are the issues we are particularly likely to reflect on at midlife, a time of significant opportunities and chal- lenges when we take stock and ask, “What next?” and “How can I feel better about my life?” and reevaluate our priorities. 1 Mose_0771065043_xp_01_r1.qxd 9/25/06 3:40 PM Page 2 2 Women Confidential We have so many needs and desires. In my career/life-planning workshops with managers and professionals, I am always aware of the different ways in which men and women identify and rank their values. The most striking difference is not in the values themselves or how they are ranked, although there are differences, but in how the lists are completed. The men finish the exercise in a few minutes and move on to the next question. The women write the list. Then they erase it. Then they do it again.