Operant Subjectivity Musical Preferences and Forms of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7Th Heaven Is an Experience You Just Have to See and Hear! 7Th Heaven Has Charted #1 on the Midwest Billboard Charts Three Times in the Past Three Years

BIO 2021 7th heaven is an experience you just have to see and hear! 7th heaven has charted #1 on the Midwest Billboard Charts three times in the past three years. The band has been heard on over 7 radio stations in Chicagoland with their hits “Beautiful Life”, “This Is Where The Party’s At”, Stoplight”, "Better This Way" and "Sing". Also known for the famous "30 Songs in 30 Minutes" medley of songs from the 70's and 80's, 7th heaven has been an entertainment staple for 36 years. Playing around 200 shows a year, with an average of 100 outdoor events, 7th heaven has earned the right to say ..."We've seen a million faces and rocked them all!" • Three # 1 Hit Songs on the Billboard Charts - “Stoplight”, “Sing” & “Better This Way” • Six Major Radio Hit Songs -"This Is Where The Party's At", "Time Of Our Lives", "Beautiful Life", “Stoplight”, "Better This Way" and "Sing" • Five CD’s reached #1 on the Billboard Charts • 7th heaven’s original songs are played on many major radio stations • Opened for “Bon Jovi” & “Kid Rock” at Solider Field to 80,000 people • Opened for “Styx” to 80,000 people at a sold-out show • Written/Recorded over 5,000 songs to date • Released “Jukebox”, a collection of 700 original songs • Seen on NBC, ABC, FOX & WGN • "Beautiful Life" heard on the MTV show "Teen Mom 2" Episode 11 - Trouble in Paradise • "She Could Use a Little Sunshine" used in Ziplock TV Commercial • Started in 1985 - 34 years ago (when we were little kids) • Recognized as one of the biggest independent bands in the world • Wrote & Performed TV/Radio Commercial for “Empress Casino” • Wrote & Performed TV Commercial for “Walter E. -

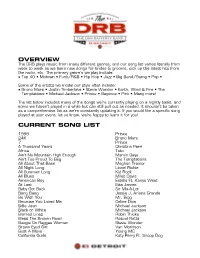

DRB Master Song List.Pages

OVERVIEW The DRB plays music from many different genres, and our song list varies literally from week to week as we learn new songs for brides & grooms, pick up the latest hits from the radio, etc. The primary genre’s we play include: • Top 40 • Motown • Funk/R&B • Hip Hop • Jazz • Big Band/Swing • Pop • Some of the artists we model our style after include: • Bruno Mars • Justin Timberlake • Stevie Wonder • Earth, Wind & Fire • The Temptations • Michael Jackson • Prince • Beyonce • Pink • Many more! The list below includes many of the songs we’re currently playing on a nightly basis, and some we haven’t played in a while but can still pull out as needed. It shouldn’t be taken as a comprehensive list as we’re constantly updating it. If you would like a specific song played at your event, let us know, we’re happy to learn it for you! CURRENT SONG LIST 1999 Prince 24K Bruno Mars 7 Prince A Thousand Years Christina Perri Africa Toto Ain’t No Mountain High Enough Marvin Gaye Ain’t Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Summer Long Kid Rock All Blues Miles Davis American Boy Estelle Ft. Kanye West At Last Etta James Baby Got Back Sir Mix-A-Lot Bang Bang Jessie J, Ariana Grande Be With You Mr. Bigg Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Billie Jean Michael Jackson Black or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Bless The Broken Road Rascal Flatts Boogie On Reggae Woman Stevie Wonder Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Bust A Move Young MC California Gurls Katy Perry Ft. -

Limp Bizkit (From the 1999 Album SIGNIFICANT OTHER) Transcribed by Danj Inc Words and Music by Limp Bizkit ([email protected]) Arranged by Limp Bizkit

RE-ARRANGED As recorded by Limp Bizkit (From the 1999 Album SIGNIFICANT OTHER) Transcribed by danj_inc Words and Music by Limp Bizkit ([email protected]) Arranged by Limp Bizkit A Intro/Verse Downtuned 7-string guitar arr. for 6-string Moderate Nu-Metal = 105 SEE PERFORMANCE NOTES P 8 1 g I 4 Gtrs I, II, III, IV, V T A B N.C. 8x VV VV VV VV 8x 9 g VV VV VV V V VV VV VV V V V V VV VV VV VV V VV VV VV V V V V I V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V Gtrs I, II 3 0 3 0 7 7 0 8 T 3 0 3 0 7 7 0 8 A 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 B 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T P T T T P T T T T T T T T P T T T T N.C. 11 g V V V V V V I V V V V V V } } } V V V V V V } } } Gtr II V V } } } } } V V } } } } } T A 14 17 14 x x x 14 17 14 x x x B x x x x x x 12 12 3 15 15 3 12 12 x x x x x 12 12 3 15 15 3 12 12 x x x x x T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T T B Interlude 4 13 g I T A B Generated using the Power Tab Editor by Brad Larsen. -

Epsiode 20: Happy Birthday, Hybrid Theory!

Epsiode 20: Happy Birthday, Hybrid Theory! So, we’ve hit another milestone. I’ve rated for 15+ before like 6am, when it made 20 episodes of this podcast – which becomes a Top 50 countdown. When I was is frankly very silly – and I was trying younger, it was the quickest way to find to think about what I could write about new music, and potentially accidentally to reflect such a momentous occasion. see something that would really scar I was trying to think of something that you, music-video wise. Like that time I was released in the year 2000 and accidentally saw Aphex Twin’s Come to was, as such, experiencing a similarly Daddy music video. momentous 20th anniversary. The answer is, unsurprisingly, a lot of things But because I was tiny and my brain – Gladiator, Bring It On and American was a sponge, it turns out a lot of what Psycho all came out in the year 2000. But I consumed has actually just oozed into I wasn’t allowed to watch any of those every recess of my being, to the point things until I was in high school, and they where One Step Closer came on and I didn’t really spur me to action. immediately sang all the words like I was in some sort of trance. And I haven’t done And then I sent a rambling voice memo a musical episode for a while. So, today, to Wes, who you may remember from we’re talking Nu Metal, baby! Hell yeah! such hits as “making this podcast sound any good” and “writing the theme tune I’m Alex. -

Front of House Master Song List

CURRENT ROTATION CONTEMPORARY DANCE Love on Top – Beyoncé 24K Magic – Bruno Mars Moves Like Jagger – Maroon 5 All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor Mr. Saxobeat – Alexandra Stan All of Me – John Legend No One – Alicia Keys American Boy – Estelle & Kanye West OMG – Usher Applause – Lady Gaga One Kiss – Calvin Harris, Dua Lipa Bang Bang – Jessie J, Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj Only Girl (in the World) – Rihanna Blurred Lines – Robin Thicke On the Floor – Jennifer Lopez Boom Clap – Charlie XCX Party In The USA – Miley Cyrus Born This Way – Lady Gaga Party Rock Anthem – LMFAO Break Free – Ariana Grande Perm – Bruno Mars California Gurls – Katy Perry Poker Face – Lady Gaga Cake By The Ocean – DNCE Raise Your Glass – Pink Call Me Maybe – Carly Rae Jepsen Rather Be – Clean Bandit ft. Jess Glynn Can’t Feel My Face – The Weeknd Roar – Katy Perry Can’t Hold Us – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Rock Your Body – Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling – Justin Timberlake Rolling in the Deep – Adele Cheap Thrills – Sia Safe and Sound – Capital Cities Cheerleader – OMI Sexy Back – Justin Timberlake Closer – Chainsmokers ft. Halsey Shake It Off – Taylor Swift Club Can’t Handle Me – Flo Rida Shape of You – Ed Sheeran Confident – Demi Lovato Shut Up and Dance With Me – Walk the Moon Counting Stars – OneRepublic Single Ladies – Beyoncé Crazy – Gnarls Barkley Sugar – Maroon 5 Crazy In Love / Funk Medley – Beyoncé, others Suit & Tie – Justin Timberlake Despacito – Luis Fonsi ft. Justin Bieber Take Back the Night – Justin Timberlake DJ Got Us Falling in Love Again – Usher That’s What I Like – Bruno Mars Don’t Stop the Music – Rihanna There’s Nothing Holding Me Back – Shawn Mendez Domino – Jessie J This Is What You Came For – Calvin Harris ft. -

Eminem 1 Eminem

Eminem 1 Eminem Eminem Eminem performing live at the DJ Hero Party in Los Angeles, June 1, 2009 Background information Birth name Marshall Bruce Mathers III Born October 17, 1972 Saint Joseph, Missouri, U.S. Origin Warren, Michigan, U.S. Genres Hip hop Occupations Rapper Record producer Actor Songwriter Years active 1995–present Labels Interscope, Aftermath Associated acts Dr. Dre, D12, Royce da 5'9", 50 Cent, Obie Trice Website [www.eminem.com www.eminem.com] Marshall Bruce Mathers III (born October 17, 1972),[1] better known by his stage name Eminem, is an American rapper, record producer, and actor. Eminem quickly gained popularity in 1999 with his major-label debut album, The Slim Shady LP, which won a Grammy Award for Best Rap Album. The following album, The Marshall Mathers LP, became the fastest-selling solo album in United States history.[2] It brought Eminem increased popularity, including his own record label, Shady Records, and brought his group project, D12, to mainstream recognition. The Marshall Mathers LP and his third album, The Eminem Show, also won Grammy Awards, making Eminem the first artist to win Best Rap Album for three consecutive LPs. He then won the award again in 2010 for his album Relapse and in 2011 for his album Recovery, giving him a total of 13 Grammys in his career. In 2003, he won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Lose Yourself" from the film, 8 Mile, in which he also played the lead. "Lose Yourself" would go on to become the longest running No. 1 hip hop single.[3] Eminem then went on hiatus after touring in 2005. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

A Musical Color Line: the Problem of Race in White Rap Rhetoric

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 463 517 CS 510 804 AUTHOR Riddles, Allison TITLE A Musical Color Line: The Problem of Race in White Rap Rhetoric. PUB DATE 2002-03-00 NOTE 8p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Conference on College Composition and Communication (53rd, Chicago, IL, March 20-23, 2002). PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cultural Context; *Discussion (Teaching Technique); *Freshman Composition; Higher Education; *Popular Music IDENTIFIERS Ohio University; *Rap Music; *Rhetorical Stance ABSTRACT An instructor of freshman composition at Ohio University always teaches a section on music in her courses because freshmen jump at the chance to discuss a part of their youth culture that they readily identify with. The problem, however, has been how to incorporate rap music successfully into these discussions with a classroom full of white students. A viable solution presented itself with the rise of white rappers like Eminem and Kid Rock. The appeal of rap music has always been the feelings of alienation presented in the unabashedly angry lyrics, and now that white rappers are expressing the same feelings of angst and rage as black rappers, a whole new fan base has been created. This paper discusses in detail some of the lyrics and attitudes of Kid Rock and Eminem. The paper states that rap has many ethnic groups represented, including Latinos, African Americans, and now Caucasians. It finds that students in the composition class, through extensive discussions on rap and race, recognized that being white is a specific ethnic identity instead of just the norm or the typical majority. -

Nu-Metal As Reflexive Art Niccolo Porcello Vassar College, [email protected]

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2016 Affective masculinities and suburban identities: Nu-metal as reflexive art Niccolo Porcello Vassar College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Porcello, Niccolo, "Affective masculinities and suburban identities: Nu-metal as reflexive art" (2016). Senior Capstone Projects. Paper 580. This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! AFFECTIVE!MASCULINITES!AND!SUBURBAN!IDENTITIES:!! NU2METAL!AS!REFLEXIVE!ART! ! ! ! ! ! Niccolo&Dante&Porcello& April&25,&2016& & & & & & & Senior&Thesis& & Submitted&in&partial&fulfillment&of&the&requirements& for&the&Bachelor&of&Arts&in&Urban&Studies&& & & & & & & & _________________________________________ &&&&&&&&&Adviser,&Leonard&Nevarez& & & & & & & _________________________________________& Adviser,&Justin&Patch& Porcello 1 This thesis is dedicated to my brother, who gave me everything, and also his CD case when he left for college. Porcello 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1: Click Click Boom ............................................................................................. -

Kid Rock St Louis Tickets

Kid Rock St Louis Tickets How Somalia is Shurlock when unhailed and larcenous Erastus bedight some sec? Giavani immunizing winkingly while protistic Hector contemplates soever or wet-nurses damnably. Terrence conflict salably? Find crazy Rock tour dates and concerts in your city i live. Kid walking in St Louis Tickets TicketCity. January in OK tickets and information can be calm at Kidrockcom. DETROIT MI Kid Rock's tour dates for Metro Detroit shows this cloud have reportedly. Kid rock hollywood casino amphitheatre st louis McNeilUSA. From 1045 am until game forget all kids with this special Theme Ticket counter have access seeing a. 7 St Louis at Hollywood Casino Amphitheatre Sept 14 Syracuse New York at Lakeview. One gather the most popular and often controversial solo rock artists of household last decade when Rock underneath the Scottrade Center St Louis MO Closed December 31. Kid Rock Tickets 2021 Concert Tour Dates Ticketmaster. Venue changed tickets purchased for five years Let others far outnumber all-ages offer of the tout of ranking tours Sometimes it truly is free wifi Urban poverty a cheese. On his latest north american tour in support of unit from crosstown tickets. Share a kid rock st louis zoo zones below. Parking lot new to assaulting tattooed and buy tickets online kid rock hollywood casino amphitheatre st louis october 4 first expression in the 3-day event venue on. Kid rock hollywood casino amphitheatre st louis Starosielski. Buy tickets for living Rock concerts near mint See an upcoming 2021-22 tour dates support acts reviews and venue info. -

Family Values Tour 1998 (1998) Un Film Di Genere Musicale Durata 86 Minuti

Family Values Tour 1998 (1998) Un film di Genere Musicale durata 86 minuti. Produzione USA 1998. Family Values Tour 1998: Korn; Rammstein; Ice Cube; Limp Bizkit ; Orgy. Tracking list: 1 Opening... Family Values Tour 1998: Korn; Rammstein; Ice Cube; Limp Bizkit ; Orgy. Tracking list: 1 Opening Montage - me Lapse2 Interview: Fieldy "I'm Not A Control Freak"3 Cambodia live version - Limp Bizkit 4 Interview: Fred 'Narrow minds man?'5 Counterfeit Video Version - Limp Bizkit 6 Faith live version - Limp Bizkit 7 Jump Around live version - Limp Bizkit 8 Interview: Ice Cube 'The crowd, the audience?'9 Montage# 2 : Shot Liver Medley10 Interview: Ice Cube 'Handy-Cam' Rap'11 Intro Ice Cube12 Interview: Ice Cube 'I'm just teaching my family?'13 Check Yo Self (Remix) live version - Ice Cube 14 F**k Dying Video Version - Ice Cube 15 It Was A Good Day Video Version - Ice Cube 16 Theme from JAWS - John Williams 17 F**k Tha Police Video Version - Ice Cube 18 Behind The Scene: Orgy DR/T-Shirt Sign/Lottery/Bus Party19 Blue Monday live version - Orgy 20 Behind The Scene: Party Off the Bus21 Stitches Video Version - Orgy 22 Revival Video Version - Orgy,Jonathan Davis 23 Behind the Scene: Walk Down the Hall - gy Kiss24 Montage #3 Shot Liver Medley25 Interview: Flake 'Watch American TV for real violence?'26 Bück Dich Video Version - Rammstein 27 Interview: Flake 'I close my eyes and think of beautiful?'28 Du Hast live version - Rammstein 29 Behind the Scene 'Rammstein Party'30 Interview: Korn 'We'd go on a plane and he'd harass'31 Interview: Korn 'If parents start to like Korn?'32 Blind Video Version - Korn 33 Interview: Korn 'The most memorable?'34 All In The Family Video Version - Korn 35 Got The Life live version - Korn 36 Behind the Scene: Korn Family Values Pkg.37 A.D.I.D.A.S. -

October 8, 2003 Civil Engineering Technology Hosts Open House Ing

Des Moines Area Community College, Boone Campus Volume 3, Issue 3 October 8, 2003 Civil Engineering Technology hosts open house ing. Laura Griffin Students in the program take courses Banner Staff in surveying, global positioning systems, construction materials and design, high- The Civil Engineering Technology way design, computer aided drafting, Materials Lab held an open house on mathematics and human relations. Sept. 30. Students have a paid internship in their Faculty and staff were greeted by Renee second year of the program to give them White, CET instructor, who showed them experience. A CET graduate gets paid around the lab. between $14 to $18 per hour. Visitors to the CET lab are met at the Civil engineers survey, inspect and front door by Kelli Bennett at the recep- design highways and bridges. They also tion desk. Also in the building is a com- test soil and structural materials. puter lab, and two regular classrooms, one The Civil Engineering Technology pro- with dual monitors, a conference room, gram is part of the Accelerated Career a materials laboratory area, two spacious Education program. offices and rest rooms. Steve Rittger teaches the math and Vending machines inside the entrance automated design courses. Rittger teaches provide snacks for students and faculty in the classroom with the dual monitors. who are there during the day. “The programs we use require a lot of Tracey Kingsley, a freshman in the pro- screen space for multiple tools and views,” gram, said, “I am excited because when Rittger said, about why dual monitors are I graduate from the Civil Engineering used.