Ben Goldacre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cochrane Afraid to Challenge the Diagnostic Acu- Men Ofhis Ancestors Or Peers

place or at the wrong time. He was not The Cochrane afraid to challenge the diagnostic acu- men ofhis ancestors or peers. He Collaboration believed that clinical questions often were answered on the basis oftests, Lessons for Public Health rather than on common sense. Practice and Evaluation? Obstetrics offered Cochrane an example ofthe practices ofthe day. Like many other fields ofmedicine, MIRUAM ORLEANS, PHD obstetrics adhered to treatments that perhaps were oftraditional or emo- tional value but which had little basis Archie Cochrane undoubtedly in science. The therapeutic use ofiron wanted to reach providers of and vitamins, the basis for extended health care with his ideas, but he lengths ofstay in hospitals following probably never thought that he would childbirth, and the basis for deciding father a revolution in the evaluation of how many maternity beds were needed medical practices. in Britain were all questioned by In his book ofonly 92 pages, Cochrane, who believed that these "Effectiveness and Efficiency: Random matters could and should be investi- Reflections on Health Services," pub- gated in trials. lished by the Nuffield Provincial Hos- Although Cochrane was by no pitals Trust in 1972, he cast a critical means the first clinician-epidemiologist eye on health care delivery, on many to suggest that randomized controlled A. L Cochrane well-respected and broadly applied trials were an appropriate means of interventions, and on whole fields of deciding questions regarding the effi- were appropriate for laboratory studies medicine and their underlying belief ciency and benefit oftreatment, I can and probably some animal and behav- systems (1). -

The Cochrane Collaboration: an Introduction P

toolbox research are unlikely to have a high ticular research questions. This is why become dated and irrelevant. Because of number of clinically based trials direct the evidence-based supplement will also this we will seek to both review our core ed towards them. Equally journals endeavour to include these when appro list regularly and also look beyond this which publish qualitative research are priate and well conducted. list. If any reader feels any particular disadvantaged in a table based on ran It is equally important that only well article is important and should be domised-controlled trials or systematic conducted and reported randomised included please feel free to contact the review. However rating journals on the controlled trials or systematic reviews editorial office with the reference. We basis of their number of citations is are included. If we were to look in detail will then include it in our review equally open to challenge as noted at both the randomised-controlled tri process. Provided it passes the quality above. als and systematic reviews identified by filters it will appear in the supplement. Well-conducted randomised -con- the search strategy above many would trolled trials and systematic reviews not meet our quality criteria (see page Acknowledgements based on them have great potential for 32). This supplement will endeavour to To Christine Allot, Librarian, at the Berkshire Health Authority who conducted the answering questions about whether a include only good quality articles relat medline searches. treatment does more harm than good ing to treatment, diagnostic testing, particularly in the clinical situation. -

The Opportunities and Challenges of Pragmatic Point-Of-Care Randomised Trials Using Routinely Collected Electronic Records: Evaluations of Two Exemplar Trials

HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENT VOLUME 18 ISSUE 43 JULY 2014 ISSN 1366-5278 The opportunities and challenges of pragmatic point-of-care randomised trials using routinely collected electronic records: evaluations of two exemplar trials Tjeerd-Pieter van Staa, Lisa Dyson, Gerard McCann, Shivani Padmanabhan, Rabah Belatri, Ben Goldacre, Jackie Cassell, Munir Pirmohamed, David Torgerson, Sarah Ronaldson, Joy Adamson, Adel Taweel, Brendan Delaney, Samhar Mahmood, Simona Baracaia, Thomas Round, Robin Fox, Tommy Hunter, Martin Gulliford and Liam Smeeth DOI 10.3310/hta18430 The opportunities and challenges of pragmatic point-of-care randomised trials using routinely collected electronic records: evaluations of two exemplar trials Tjeerd-Pieter van Staa,1,2* Lisa Dyson,3 Gerard McCann,4 Shivani Padmanabhan,4 Rabah Belatri,4 Ben Goldacre,1 Jackie Cassell,5 Munir Pirmohamed,6 David Torgerson,3 Sarah Ronaldson,3 Joy Adamson,3 Adel Taweel,7 Brendan Delaney,7 Samhar Mahmood,7 Simona Baracaia,7 Thomas Round,7 Robin Fox,8 Tommy Hunter,9 Martin Gulliford10 and Liam Smeeth1 1Department of Non-Communicable Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK 2Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands 3York Trials Unit, York University, York, UK 4Clinical Practice Research Datalink, Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, London, UK 5Division of Primary Care and Public Health, Brighton and Sussex Medical School, University of Brighton, Brighton, UK 6The Wolfson Centre for -

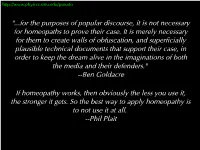

Homeopathy Works, Then Obviously the Less You Use It, the Stronger It Gets

http://www.physics.smu.edu/pseudo "...for the purposes of popular discourse, it is not necessary for homeopaths to prove their case. It is merely necessary for them to create walls of obfuscation, and superficially plausible technical documents that support their case, in order to keep the dream alive in the imaginations of both the media and their defenders." --Ben Goldacre If homeopathy works, then obviously the less you use it, the stronger it gets. So the best way to apply homeopathy is to not use it at all. --Phil Plait http://www.physics.smu.edu/pseudo “Alternative Medicine” - Homeopathy - Supplementary Material for CFB3333/PHY3333 Professors John Cotton, Randy Scalise, and Stephen Sekula http://www.physics.smu.edu/pseudo ● FRINGE ● The land of wild ideas, mostly untested or untestable. Most of these will be discarded as useless. Only some of these will make it into the frontier. ● FRONTIER ● CORE Tested (somewhat or better) ideas that could still be wrong or require significant modification. ● CORE FRONTIER ● Very well-tested ideas that are unlikely to be overturned. They may FRINGE become parts of bigger ideas, but are very unlikely to be discarded. A Depiction of Science Thanks to Eugenie Scott http://www.physics.smu.edu/pseudo HOMEOPATHY A LOOK AT THE SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE http://www.physics.smu.edu/pseudo Claim and Assessment ● Claim: homeopathic medicine can treat the diseases it claims to treat ● there are many more medicines than there have been scientific tests of those medicines, which should already tell you something. Homeopathy is like a hydra. ● Tests: ● Gold-standard medical testing: randomized, double/single-blinded, placebo-controlled, large-statistics trials http://www.physics.smu.edu/pseudo http://www.physics.smu.edu/pseudo ● Findings: ● 8 studies in the review fulfilled their review criteria ● Only about half of those were more akin to gold standard, and they tended to show no effect over placebo. -

Transparency in the Time of Constant Change

PhUSE 2014 Paper RG02 Transparency in the Time of Constant Change Todd Case, Biogen Idec, Cambridge MA, USA ABSTRACT The time has come, after years of hard work, to submit your application to the regulatory agency for review and possible approval! What a relief to be able to finally hand off all of your hard work and, wait a minute, ensure that all data can be reproducible?!? While CDISC has been widely adopted and its SDTM and AdAM models widely implemented, there is still the need to understand the process of ensuring that all the data is a reflection of how it was originally collected, which in some cases can be very challenging. This paper will discuss some more trending ways of both creating and presenting data in ways that ensure it is consumable and can be understood not only for analysis/submission purposes but also that post-approval it is transparent and that everyone who has a vested stake can review the data in an appropriate way. INTRODUCTION With the publication of Bad Pharma: How Medicine is Broken , and How We Can Fix it, by Dr. Ben Goldacre in 2013 a bright spotlight was shone on the data behind/supporting clinical trials. A large part of his thesis is that pharmaceutical companies exaggerate the efficacy of successful trials and that, in addition to drug companies, regulators , physicians (who are educated by the drug companies) and even patient groups have failed to protect us. Another rather striking revelation was that a clinical trial with positive results is twice more likely to be published than one with negative results (although it should be noted that this specifically is related to results – the protocol is always provided). -

Bad Pharma: How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients by Ben Goldacre

RCSIsmjbook review Bad Pharma: How drug companies mislead doctors and harm patients by Ben Goldacre Reviewed by Eoin Kelleher, RCSI medical student Paperback: 448 pages Publisher: Fourth Estate, London Published 2012 ISBN: 978-0-00-735074-2 Dr Ben Goldacre earned his reputation for his 2008 book Bad to affect doctors’ prescribing habits (although most doctors claim Science and his column in the Guardian newspaper of the same that their own practices have never been affected, just those of their name. In both he provides an entertaining, accessible and colleagues). Even journals, which are considered to be an unbiased well-researched exposé of poor scientific practices. Compared to source of medical knowledge, are not free from this – journal articles his first book, which played charlatans such as Gillian McKeith are regularly ghost-written by employees of drug companies and an and homoeopathists for laughs, Bad Pharma is a much more eminent academic is invited to put their name to it; this appears in sombre read. However, as a piece of investigative journalism, and the journal, again without disclosure. a resource for students, doctors and patients, it is invaluable. Drugs are tested by the people who Food for thought Goldacre opens by making a claim that: “Drugs are tested by the manufacture them, in poorly designed people who manufacture them, in poorly designed trials, on trials, on hopelessly small numbers of hopelessly small numbers of weird, unrepresentative patients, and unrepresentative patients, and analysed analysed using techniques which are flawed by design, in such a way that exaggerate the benefits of treatments. -

Drugs, Money and Misleading Evidence

Books & arts tallying up the inequalities. She recruited colleagues to gather much more data. The culmination was a landmark 1999 study on gender bias in MIT’s school of science (see go.nature.com/2ngyiyd), which reverber- ated across US higher education and forced many administrators to confront entrenched discrimination. Yet Hopkins would rather have spent that time doing science, she relates. The third story comes from Jane Willenbring, a geoscientist who in 2016 filed a formal com- plaint accusing her PhD adviser, David March- ant, of routinely abusing her during fieldwork in Antarctica years before. Marchant, who has denied the allegations, was sacked from his post at Boston University in April 2019 after an inves- tigation. Picture a Scientist brings Willenbring together with Adam Lewis, who was also a grad- uate student during that Antarctic field season and witnessed many of the events. Their conver- sations are a stark reminder of how quickly and how shockingly the filters that should govern work interactions can drop off, especially in UPRISING, LLC Biologist Nancy Hopkins campaigned for equal treatment at work for female scientists. remote environments. Lewis tells Willenbring he didn’t realize at the time that she had been as they admit on camera. scientists. Its two other protagonists are white bothered, because she did not show it. “A ton The iceberg analogy for sexual harassment is women with their own compelling stories. of feathers is still a ton,” she says. apt. It holds that only a fraction of harassment — Biologist Nancy Hopkins was shocked In stark contrast, the film shows us obvious things such as sexual assault and sex- when Francis Crick once put his hands on Willenbring, now at the Scripps Institution of ual coercion — rises into public consciousness her breasts as she worked in the laboratory. -

Philip Mirowski, Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown, New York: Verso, 2013

Book Review Symposium Philip Mirowski, Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown, New York: Verso, 2013. ISBN: 9781781680797 (cloth); ISBN: 9781781683033 (ebook); ISBN: 9781781683026 (paper) Author’s response I want to thank Antipode and the four participants for lengthy reactions to my book Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste. I think it is apparent it was written in a funk of distress; and the reviewers here invite me to step back from all that, and reflect on how it has been regarded by various readers who do not necessarily share my own particular chagrin nor my axes to grind. The experience has been salutary, and evokes a few short responses. One theme present to a greater or lesser extent in all the reviews is that, as Nick Gane puts it, I never tell the reader “what should happen next”; or, as Geoff Mann writes, “OK. So what now?”. I should confess I also get this a lot when I give talks concerning the subjects in the book. When that happens, I take the occasion to suggest that one of the primary lessons of the book directly informs my self-denying ordinance: the prohibition of offering any ‘remedies’ as conventional bullet points, like those which fill the last chapters of the torrent of crisis books which have fallen from the presses clonedead since 2008. When the Neoliberal Thought Collective (NTC) began to organize itself in the 1930s/40s, it found itself stranded in the intellectual wilderness, exiled from political power by Depression and war, and suffering internal disarray, much as the Left has experienced now. -

King's Research Portal

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30276-3 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Hurwitz, B. (2017). What Archie Cochrane learnt from a single case. Lancet, 389(10069), 594-595. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30276-3 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Evidence-Based Medicine and Archie Cochrane

Profiles in Medical Courage: Evidence-Based Medicine and Archie Cochrane “Medicine is a science of uncertainty and an art of probability.” -Sir William Osler Abstract Archibald (Archie) Cochrane is often credited with being the inspiration for evidence- based medicine. His influential 1971 book, “Effectiveness and Efficiency”, strongly criticized the lack of reliable evidence behind many common healthcare practices. His call for a collection of systematic reviews led to the creation of The Cochrane Collaboration, named in honor of him. Archie Cochrane's life was a tortuous one, which included psychoanalysis, service in two wars, and studies of pneumoconiosis, tuberculosis and healthcare delivery. In this profile of medical courage we explore not only his thoughts on healthcare but his extraordinary background that shaped his ideas. Early Life Archie Cochrane was born in 1909 in Galashiels, Scotland, a cloth manufacturing town 30 miles south of Edinburgh. His family was wealthy mill owners that instilled in Archie the principles of self-reliance and accomplishment. This was important since his father died in the First World War when Archie was 8. However, Archie was financially secure since as the first born, he inherited a private income. By all accounts, he was a bright student. After attending preparatory school at Rhos-on- Sea in Wales, Archie won a scholarship to Uppingham School in Rutland, England, where he became a school prefect and a member of the rugby team. In 1927, he won a scholarship to King’s College Cambridge, where he graduated in 1930 with honors in natural sciences. His inheritance enabled him to continue studying, and during 1931 he worked on tissue culture at the Strangeways Laboratory at Cambridge and later in Toronto. -

Histories of Medical Lobbying’

‘Histories of medical lobbying’ The lobbying of government ministers by medical professionals is a live issue. In Britain and around the world medical practitioners have become active in the pursuit of legislative change. In the UK, the AllTrials campaign co-founded by the physician-researcher Ben Goldacre continues to exert pressure on parliamentarians in a bid to force greater transparency in the publication of clinical trial results. Meanwhile, the California Medical Association advocates the legalisation of the recreational use of marijuana, and doctors in Australia refuse to release child refugees from hospital into detention centres damaging to their mental health. It was precisely the lobbying of medical humanitarians such as Médecins sans Frontières in France that effected a change in the law there in 1998, permitting undocumented immigrants with life-threatening conditions to remain in the country for medical treatment. Each of these examples represents an organised attempt on the part of medical professionals to change government policy on matters related to public health – in other words, lobbying. Yet a recent announcement by the UK cabinet office suggests that henceforth recipients of public funding will be banned from directly lobbying government ministers in the hope of changing public policy. When questioned in parliament David Cameron stated that charities should be devoting themselves to ‘good causes’ rather than ‘lobbying ministers’. Unless some qualification is forthcoming, medical researchers too will be proscribed from carrying out such activity. This insinuates that lobbying is in some way outside the proper remit of researchers, medical or otherwise. Yet even a cursory glance at the history of the medical profession’s engagement with public health reveals a longstanding and significant engagement with the political process. -

On the Clear Evidence of the Risks to Children from Non-Ionizing Radio Frequency Radiation: the Case of Digital Technologies in the Home, Classroom and Society

On the Clear Evidence of the Risks to Children from Non-Ionizing Radio Frequency Radiation: The Case of Digital Technologies in the Home, Classroom and Society Professor Tom Butler Contents Abstract ........................................................................... 2 Introduction ...................................................................... 3 Do existing Standards on Wireless Digital Technologies protect Children? ........................................................................ 3 Why are Independent Scientific Studies more Trustworthy? .. 4 What is the Reaction to the Mounting Evidence? .................. 5 How can we make Sense of Difference of Opinion among Scientists? ...................................................................... 5 What is the Significance of the U.S. NTP Study? .................... 6 What is the Proof of the Potential Toxicity and Carcinogenicity of RFR? .......................................................................... 7 What is the Evidence from Epidemiological Studies? ............... 8 What are Implications for Childhood RFR Exposure? ........... 11 What are the Risks to Children of RFR Exposure In Utero? .. 11 What are the Biological Mechanisms that Produce Ill-health in Children and Adults? ........................................................ 12 What is the Evidence that Microwave RFR Promotes the Development of Existing Cancers? ..................................... 14 Why are Existing Standards Unsafe? .................................. 15 Here be Dragons! .........................................................