Building Name

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Insurance Tower, L6, 1 Willis Street, Wellington, North Island

State Insurance Tower, L6, 1 Willis Street, Wellington, North Island View this office online at: https://www.newofficeasia.com/details/serviced-offices-level-6-1-willis-street- wellington-north-island Positioned on the 6th floor, this business centre resides within a premier high rise landmark building and commands spectacular views across the city. With floor-to-ceiling windows, this facility is flooded with natural light and provides 24 hour access with flexible tenancy agreements that are specifically tailored to your individual business requirements. There are stylish kitchen facilities and meeting rooms available in addition to a friendly receptionist who welcomes your visitors in a warm and professional manner - perfect for creating a positive first impression for your company. Transport links Nearest airport: Key features 24 hour access Access to multiple centres nation-wide Flexible contracts Furnished workspaces High-speed internet Hot desking Kitchen facilities Meeting rooms Open plan workstations Reception staff WC (separate male & female) Wireless networking Location Located in the heart of Wellington, these offices reside within New Zealand's government hub and are perfectly placed for legal professionals. The New Zealand Stock Exchange is situated close by alongside the "golden mile" which is home to an abundance of retailers and restaurants. Enjoy walking distance to beautifully landscaped parks and the waterfront and, for commuters, Wellington International Airport is situated just 11 minutes away. Points of interest within 1000 metres -

3122 the NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No

3122 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 99 Flaxmere- Takaka, Council Chambers. Peterhead Public School. Takapau, Public School. Irongate Public School. Taradale, Town Hall. Foxton, Park Street School. Tawa, Baptist Hall, Main Road. Frasertown, Public School. Te Arakura, Public School. Greenmeadows, Public School. Te Hauke, Hall. Greytown, Public School. Tc Ore Ore. Hastings- Te Reinga, Public School. Camberley Public School. Te Waiohiki Pa, Mr E. Pene's Residence. Central Public School. Titahi Bay, Tireti Hall, Tireti Road. Mahora Public School. Trentham, Kindergarten, Tawai Street. Haumoana, Public School. Trentham Y.M.C.A. Havelock North, Public School. Tuahiwi, Public School. Invercargill, St. Johns Hall. Turiroa, Public School. Iwitea Pa, Meeting House. Twizel, High School. Kaiapoi, R.S.A. Upper Hutt, City Corporation, Administration Building, Kaikoura, Courthouse. Fergusson Drive. Kokako, Public School. Waihua, Public School. Kotemari, Public School. Waikawa Bay, Public School. Levin, Public School. Waimarama, School. Linton, Military Camp. Wainuiomata- Little River, County Office. Community Centre. Puketapu Grove Maori Meeting House. Glendale Public School. Lower Hutt, Town Hall. Wainuiomata Public School. Lyttleton- Waipatu, Tamatea Club Rooms. Main Public School. Waipawa, Hall. Rapaki House. Waipukurau, Courthouse. Mahia, Peninsula Public School. Wairau Pa, Public School. Manor Park, Public School. Wairoa- Maoribank, Public School. Kobul Street Public School. Maraenui- North Clyde Public School. Maraenui Public School. St. Therese Hall. Richmond Public School. Taihoa Marae. Marewa, Public School. Wairoa College. Martinborough, Public School. Waitangirua- Masterton- Corinna Public School. Courthouse, Dixon Street. Tairangi Public School. East Public School. Wellington Harley Street Public School. Johnsonville Mall. Town Hall, Chapel Street. Mulgrave Street, Family Court Building. Mataura, Borough Council Chambers. -

Economic Development DRAFT TEXT 28/08/2008

Annual Report 2007/08 Economic development DRAFT TEXT 28/08/2008 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OUR APPROACH Wellington has enjoyed steady economic growth in recent years. Unemployment is low, incomes are relatively high, and the city has retained a healthy government and financial sector while also making progress towards developing new high-tech and creative industries. Under the Wellington Regional Strategy, economic development agency Grow Wellington has principal responsibility for promoting economic development throughout the region. We support economic development generally through provision of many of the facilities and services that make this a great place for workers and their families to live and for businesses to locate. We also provide specific support for tourism through the marketing of Positively Wellington Tourism and the attraction of iconic events. CASE STUDY: HOMEGROWN Wellington’s waterfront rocked for the Homegrown Music Festival. Held over Anzac Weekend 2008, the Vodafone Homegrown Music Festival attracted a sold- out crowd of thousands. The festival featured 33 bands and DJs across five stages. Headline acts included a who’s who of New Zealand music: Shihad, Pluto, Kora, the Mint Chicks, Opshop, Elemeno-P, Salmonella Dub, The Black Seeds, The Phoenix Foundation, and more. All stages were either indoors or in massive marquees to ensure the event could go ahead rain or shine. Art installations, street performers and stalls for arts and crafts, food and clothing all complemented the on-stage entertainment. Festival venues, all on Wellington’s waterfront, included the TSB Arena and Shed 6, Frank Kitts Park and the Lagoon. Festival organisers encouraged use of sustainable transport to and from venues, as well as recycling of food and drink containers. -

The Heritage Problem: Is Current Policy on Earthquake-Prone

Liv Henrich and John McClure The Heritage Problem is current policy on This series of earthquakes has acted as earthquake-prone heritage a wake-up call for many citizens of earthquake-prone regions and has highlighted the importance of preparing buildings too costly? for earthquakes (McClure et al., 2016). These events have also reinforced the Introduction political drive to strengthen legislative Earthquakes are a major hazard around the world policy for earthquake-prone buildings, particularly after the Canterbury earth- (Bjornerud, 2016). A recent example is New Zealand, where quakes. Earthquake resilience has become an issue in political discourse and public three major earthquake events occurred within a six-year policy in New Zealand. Although period. The 2010–11 earthquakes in Canterbury, centred earthquakes are unpredictable events, the damage they trigger can be greatly reduced close to the city of Christchurch, led to 185 fatalities, mainly through actions to ensure the resilience of due to two collapsed buildings and crumbling facades building structures (Spittal et al., 2008). The major cause of fatalities in earthquakes (Crampton and Meade, 2016). In addition, the rebuild of is the collapse of buildings (Spence, 2007), as demonstrated in the Canterbury Christchurch after the earthquakes cost $40 billion (English, earthquakes. Strengthening buildings is 2013), a large sum for a small country. Subsequent large thus a key measure to reduce harm from earthquakes, and may also provide earthquakes occurred in 2013 in Seddon (close to Wellington) economic benefits (Auckland Council, 2015). New Zealand, like many countries, and in 2016 in Kaiköura. has policies on earthquake legislation that Liv Henrich completed her MSc in Psychology at Victoria University of Wellington and is working affect these mitigation actions. -

Walk Guide (Pdf)

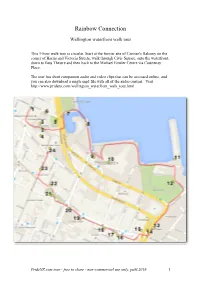

Rainbow Connection Wellington waterfront walk tour This 1-hour walk tour is circular. Start at the former site of Carmen's Balcony on the corner of Harris and Victoria Streets, walk through Civic Square, onto the waterfront, down to Bats Theatre and then back to the Michael Fowler Centre via Courtenay Place. The tour has short companion audio and video clips that can be accessed online, and you can also download a single mp3 file with all of the audio content. Visit http://www.pridenz.com/wellington_waterfront_walk_tour.html PrideNZ.com tour - free to share - non-commercial use only, publ.2016 1 Le Balcon – The Balcony corner Harris and Victoria Streets (former site) We begin the walk tour at Carmen Rupe's Le Balcon - a cabaret nightclub on the corner of Harris and Victoria Streets. Today The Balcony has been replaced by a (1) corner of Wellington City Library. In the early 1970s Dana de Milo worked there as a waitress, and in this recording she recalls some of the entertainment that was on offer. Follow the walkway up the side of the public library. Keep going until you are looking into the centre of Civic Square. To your right you will see the City Gallery (formerly the public library). To your left you will see the Wellington Town Hall. 4-min Civic Square Civic Square has been the location for a number of large rainbow gatherings, particularly Out in the Square - an annual rainbow fair which began in Newtown in 1986 and moved to Civic Square in 2008. The location was also a focal point for the (2) 2nd AsiaPacific Outgames in 2011 and a rally for marriage equality in 2012. -

Our Wellington 1 April-15 June 2021

Your free guide to Tō Tātou Pōneke life in the capital Our Wellington 1 April — 15 June 2021 Rārangi upoku Contents Acting now to deliver a city fit for the future 3 14 29 Kia ora koutou An important focus for the 2021 LTP is on Did you know you can… Planning for our future Autumn gardening tips This year will be shaped by the 2021 Long-Term infrastructure – renewing old pipes, ongoing Our contact details and Spotlight on the From the Botanic Garden Plan (LTP) and as such, is set to be a year of investment in resilient water and wastewater supply, and on a long-term solution to treat the helpful hints Long-Term Plan important, long-lasting, city-shaping decisions. 31 Every three years we review our LTP sludge by-product from sewage treatment. 5 16 Ngā huihuinga o te with a community engagement programme All this is expensive, and we’ve been Wā tākaro | Playtime Tō tātou hāpori | Our Kaunihera, ngā komiti me that sets the city-wide direction for the next working hard to balance what needs to be done with affordability. Low-cost whānau-friendly community ngā poari ā-hapori 10 years. It outlines what we will be investing in, how much it may cost, and how this will Your input into the LTP and planning for activities The life of a park ranger Council, committee and be funded. It provides guidance on how we Te Ngākau Civic Square, Let’s Get Wellington community board meetings 6 18 will make Wellington an even better place Moving and Climate Change will be critical in helping balance priorities and developing Pitopito kōrero | News Ngā mahi whakangahau 32 to live, work, play and visit as we go into the future. -

Annual Report 2017 for the Year Ended 31 December 2017

G.69 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2017 NEW ZEALAND SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA TE TIRA PŪORO O AOTEAROA TO OUR NZSO SUPPORTERS: Thank you. MAESTRO CIRCLE Drs JD & SJ Cullington Michael & Judith Bassett Carla & John Wild Denis & Verna Adam Mark De Jong Danielle Bates Anna Wilson Julian & Selma Arnhold Alfie & Susie des Tombe Philippa Bates Anita Woods Lisa Bates MNZM & Douglas Hawkins Christopher Downs & Matthew Nolan Patricia Bollard Barbara Wreford Rex Benson Michiel During & Cathy Ferguson Hugh & Jill Brewerton Dr Alan Wright Donald & Susan Best Tania Dyett Corinne Bridge-Opie Mr Christopher Young Peter Biggs CNZM & Mary Biggs Stephen & Virginia Fisher JE Brown Anonymous (18) Sir Roderick & Gillian, Lady Deane J. S. Fleming Mary E Brown Peter Diessl ONZM & Carolyn Diessl Ian Fraser & Suzanne Snively Robert Carew Dame Bronwen Holdsworth DNZM Belinda Galbraith Noel Carroll VINCENT ASPEY SOCIETY Dr Hylton Le Grice CNZM, OBE Russell & Judy Gibbard Stuart & Lizzie Charters (NOTIFIED LEGACIES) & Ms Angela Lindsay Michael & Creena Gibbons Lorraine & Rick Christie Leslie Austin Peter & Joanna Masfen Mrs Patricia Gillion Lady Patricia Clark Vivian Chisholm Paul McArthur & Danika Charlton Dagmar Girardet Jeremy Commons & the late Gillian Clark-Kirkcaldie Julie Nevett Garry & Susan Gould David Carson-Parker Bryan Crawford Les Taylor QC Laurence Greig Prue Cotter Murray Eggers Anonymous (2) Dr Elizabeth Greigo Colin & Ruth Davey D J Foley Dr John Grigor Rene de Monchy Maggie Harris Cliff Hart David & Gulie Dowrick Eric Johnston & Alison -

Agenda of Ordinary Council Meeting

COUNCIL 27 FEBRUARY 2019 ORDINARY MEETING OF WELLINGTON CITY COUNCIL AGENDA Time: 9:30am Date: Wednesday, 27 February 2019 Venue: Committee Room 1 Ground Floor, Council Offices 101 Wakefield Street Wellington MEMBERSHIP Mayor Lester Councillor Calvert Councillor Calvi-Freeman Councillor Dawson Councillor Day Councillor Fitzsimons Councillor Foster Councillor Free Councillor Gilberd Councillor Lee Councillor Marsh Councillor Pannett Councillor Sparrow Councillor Woolf Councillor Young Have your say! You can make a short presentation to the Councillors at this meeting. Please let us know by noon the working day before the meeting. You can do this either by phoning 04-803-8334, emailing [email protected] or writing to Democracy Services, Wellington City Council, PO Box 2199, Wellington, giving your name, phone number, and the issue you would like to talk about. COUNCIL 27 FEBRUARY 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 27 FEBRUARY 2019 Business Page No. 1. Meeting Conduct 5 1. 1 Karakia 5 1. 2 Apologies 5 1. 3 Announcements by the Mayor 5 1. 4 Conflict of Interest Declarations 5 1. 5 Confirmation of Minutes 5 1. 6 Items not on the Agenda 5 1. 7 Public Participation 6 2. General Business 7 2.1 Town Hall Strengthening and Music Hub 7 Presented by Mayor Lester 3. Committee Reports 63 3.1 Report of the Regulatory Processes Committee Meeting of 13 February 2019 63 Proposed road stopping - Land adjoining 42 View Road, Houghton Bay Presented by Councillor Sparrow 63 Road stopping and land exchange - Legal road in Mansfield Street adjoining 3 Roy Street, Newtown Presented by Councillor Sparrow 63 Page 3 COUNCIL 27 FEBRUARY 2019 4. -

Map of Wellington City Attractions

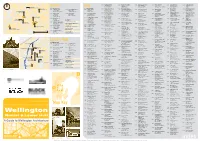

City Attractions ◆ 1. Colonial Cottage Museum ◆ 2. National War Memorial & Carillon ◆ 3. Cricket Museum/Basin Reserve ◆ 4. Mount Victoria Lookout ◆ 5. Embassy Theatre ◆ 6. The Film Archive ◆ 7. St James Theatre ◆ 8. Kura Gallery ◆ 9. Downstage Theatre 34 ◆10. Bats Theatre ◆11. Freyberg Pool ◆12. Overseas Terminal ◆13. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa ◆14. Circa Theatre ◆15. The Opera House ◆16. Department of Conservation Visitor Centre ◆17. Wellington Convention Centre/ 33 65 Michael Fowler Centre/ Wellington Town Hall ◆18. Wellesley Boat ◆19. Civic Square/City Gallery/ 32 30 Capital E/Wellington City Library/ 31 Wellington i-SITE Visitor Centre 29 ◆20. Adam Art Gallery 28 ◆21. Helipro ◆22. TSB Bank Arena ◆23. Museum of Wellington City & Sea 64 ◆24. New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts 27 ◆25. Cable Car/To Cable Car Museum/ To Carter Observatory/To Botanic 63 Garden 62 ◆26. Botanic Garden ◆27. Government Buildings Historic Reserve ◆28. Parliament Buildings/Beehive 61 ◆29. Archives New Zealand ◆ 60 30. Wellington Cathedral 26 56 59 ◆31. National Library/ 25 58 Alexander Turnbull Library 24 ◆ 57 32. Old St Paul’s 55 ◆33. Thorndon Pool 54 53 23 ◆34. Katherine Mansfield Birthplace 21 52 22 Accommodation Providers 19 35. Brentwood Hotel 20 • 18 •36. Mercure Hotel Willis Street •37. Mercure Hotel Wellington 51 16 48 17 38. Comfort Hotel Wellington 47 • 14 12 39. Wellywood Backpackers 50 49 13 •40. Base Backpackers Wellington 11 • 46 45 •41. YHA Wellington 15 •42. The Bay Plaza Hotel 44 43 43. Copthorne Hotel Oriental Bay •44. Museum Hotel 8 42 •45. At Home Wellington City 41 6 •46. -

A Guide to Wellington Architecture

1908 Tramways Building 1928 Evening Post Building 1942 Former State Insurance 1979 Freyburg Building 1987 Leadenhall House 1999 Summit Apartments 1 Thorndon Quay 82 Willis St Office Building 2 Aitken St 234 Wakefield St 182 Molesworth St 143 Lambton Quay Futuna Chapel John Campbell 100 William Fielding 36 MOW under Peter Sheppard Craig Craig Moller 188 Jasmax 86 5 Gummer & Ford 60 Hoogerbrug & Scott Architects by completion date by completion date 92 6 St Mary’s Church 1909 Harbour Board Shed 21 1928 Former Public Toilets 1987 Museum Hotel 2000 VUW Adam Art Gallery Frederick de Jersey Clere 1911 St Mary’s Church 2002 Karori Swimming Pool 1863 Spinks Cottage 28 Waterloo Quay (converted to restaurant) 1947 City Council Building 1979 Willis St Village 90 Cable St Kelburn Campus 170 Karori Rd 22 Donald St 176 Willis St James Marchbanks 110 Kent & Cambridge Terraces 101 Wakefield St 142-148 Willis St Geoff Richards 187 Athfield Architects 8 Karori Shopping Centre Frederick de Jersey Clere 6 Hunt Davis Tennent 7 William Spinks 27 City Engineer’s Department 199 Fearn Page & Haughton 177 Roger Walker 30 King & Dawson 4 1909 Public Trust Building 1987 VUW Murphy Building 2000 Westpac Trust Stadium 1960 Futuna Chapel 2005 Karori Library 1866 Old St Paul's Church 131-135 Lambton Quay 1928 Kirkcaldie & Stains 1947 Dixon St Flats 1980 Court of Appeal & Overbridge 147 Waterloo Quay 62 Friend St 247 Karori Rd 34-42 Mulgrave St John Campbell 116 Refurbishments 134 Dixon St cnr Molesworth & Aitken Sts Kelburn Campus Warren & Mahoney Hoogerbrug Warren -

Death of Former Principal, Anthony (Tony) Brough

Death of former principal, Anthony (Tony) Brough We have recently learned of the death of former Principal Anthony (Tony) Brough, who died peacefully in Nelson in November, aged 89 years. He was Principal from 1990 – 1995. Tony, along with his wife Barbara, made a huge contribution to College life. They were well-liked and respected by teachers, parents, and students, and Tony’s tenure is a significant part of College history. Tony was the 13th Principal, the first lay Principal and the first principal to manage College House as a mixed hall of residence. He presided over CH as it grew through the addition of Hardie and Beadel houses. Our thoughts are with his family at this very sad time. CH Alumni are part of the team to win prestigious engineering award Last week, the NZ Transport Agency, KiwiRail and the North Canterbury Transport Infrastructure group (NCTIR) won the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) People’s Choice Award. This award celebrates the world’s top civil engineering projects and sets the benchmark for excellence in construction and design. It is decided by a public vote – truly reflecting what the local people who benefit from each project really think! We would like to congratulate CH alumni who have been part of the huge team working on this project – Rolly (David) Rowland (2004), Daniel Headifen (1995), Hannah Willis (nee Lord) (2010/11) and Frances Neeson (2005/06). NZ Transport Agency Regional Director Steve Mutton, chair of the NCTIR Board, said it was a collective effort that resulted in engineering excellence, and every crew member – past and present - should feel proud of themselves. -

Regional Resident Survey on Regional

1: Use of amenities This chapter examines recent use of amenities. For those amenities that are available for most of the year (including venues and attractions such as Te Papa or Kapiti Island) the time-scale asked about was ‘use in the past year’. For amenities that are more occasional (including events such as World of Wearable Art or the Ambulance Service) the time-scale was ‘use in the past five years’. Within this report, a ‘user’ was someone who had used or visited that amenity within these time-scales. Use of amenities by all residents in the region Results for amenities that are available most of the year are described in the chart overleaf. © COLMAR BRUNTON 2011 – Page: 20 Amenities used in past 12 months % that HAVE used in past year le Papa 51% 23% 23% 77 Westpac Stadium 5% ]0% 20% 41% 59 Wellington Botanic Gardens 17% 41% 58 lSB Arena 2� 5� ] 47 Michael Fowler Centre � 24% 58% ] 42 Wellington Zoo] 1% 2', ', 21% 64% 36 Wellington City Gallery 41% � 17% 64% 1 35 New Dowse ", 14% 67% 2 31 Wgtn Museum of City & Sea � 17% 71% 1 28 Pataka Museum and Gallery � 12% 70% 3% 27 Zealandia , :'" 1 7% 73% 1 26 Downstage lhealre , .', 13% 79% 1 20 le Rauparaha Arena 18 NZ Symphon y Orchestra � 7% 87% 1 13 Pukaha Mount Bruce wildlife centre 1� 9% 87% 2 11 Kapiti Island 1� 5% 94% 6 More than twelve times Seven to twelve times Four to six times • Two to three times .Once • Have not used in past 12 months • Have not heard of this QA1d) How often hdve you persondlly used/visited [Amenity] ..