Terrestrial Isopoda of Arkansas David Causey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anchialine Cave Biology in the Era of Speleogenomics Jorge L

International Journal of Speleology 45 (2) 149-170 Tampa, FL (USA) May 2016 Available online at scholarcommons.usf.edu/ijs International Journal of Speleology Off icial Journal of Union Internationale de Spéléologie Life in the Underworld: Anchialine cave biology in the era of speleogenomics Jorge L. Pérez-Moreno1*, Thomas M. Iliffe2, and Heather D. Bracken-Grissom1 1Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Biscayne Bay Campus, North Miami FL 33181, USA 2Department of Marine Biology, Texas A&M University at Galveston, Galveston, TX 77553, USA Abstract: Anchialine caves contain haline bodies of water with underground connections to the ocean and limited exposure to open air. Despite being found on islands and peninsular coastlines around the world, the isolation of anchialine systems has facilitated the evolution of high levels of endemism among their inhabitants. The unique characteristics of anchialine caves and of their predominantly crustacean biodiversity nominate them as particularly interesting study subjects for evolutionary biology. However, there is presently a distinct scarcity of modern molecular methods being employed in the study of anchialine cave ecosystems. The use of current and emerging molecular techniques, e.g., next-generation sequencing (NGS), bestows an exceptional opportunity to answer a variety of long-standing questions pertaining to the realms of speciation, biogeography, population genetics, and evolution, as well as the emergence of extraordinary morphological and physiological adaptations to these unique environments. The integration of NGS methodologies with traditional taxonomic and ecological methods will help elucidate the unique characteristics and evolutionary history of anchialine cave fauna, and thus the significance of their conservation in face of current and future anthropogenic threats. -

Mitochondrial DNA Variability and Wolbachia Infection in Two Sibling Woodlice Species

Heredity 83 (1999) 71±78 Received 2 November 1998, accepted 15 March 1999 Mitochondrial DNA variability and Wolbachia infection in two sibling woodlice species ISABELLE MARCADE , CATHERINE SOUTY-GROSSET, DIDIER BOUCHON, THIERRY RIGAUD & ROLAND RAIMOND* Universite de Poitiers, Laboratoire de GeÂneÂtique et Biologie des Populations de CrustaceÂs, UMR CNRS 6556, 40 avenue du Recteur Pineau, 86022 Poitiers Cedex, France Several morphological races and subspecies have been described and later included within the terrestrial isopod species Porcellionides pruinosus. During our study of this species, we have worked on specimens from France, Greece, Tunisia and Re union island. Laboratory crosses have revealed two separate groups of populations: French populations (four localities) in one group, and those from Tunisia, Re union island and Greece in the other. French individuals were reproductively isolated from those of the other populations. We have undertaken a survey of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) polymorphism in these seven populations. We observed two groups of mitotypes corresponding to the two groups of populations. Interfertility experiments between populations and the mitochondrial genetic distances between mitotypes both suggest the presence of two dierent species, one in France and one in Greece, Tunisia and Re union island. The two species harbour, respectively, two dierent Wolbachia lines. Another feature of the molecular genetic analysis was the apparent mitochondrial monomorphism in the French populations and the low variability -

Seed Ecology Iii

SEED ECOLOGY III The Third International Society for Seed Science Meeting on Seeds and the Environment “Seeds and Change” Conference Proceedings June 20 to June 24, 2010 Salt Lake City, Utah, USA Editors: R. Pendleton, S. Meyer, B. Schultz Proceedings of the Seed Ecology III Conference Preface Extended abstracts included in this proceedings will be made available online. Enquiries and requests for hardcopies of this volume should be sent to: Dr. Rosemary Pendleton USFS Rocky Mountain Research Station Albuquerque Forestry Sciences Laboratory 333 Broadway SE Suite 115 Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA 87102-3497 The extended abstracts in this proceedings were edited for clarity. Seed Ecology III logo designed by Bitsy Schultz. i June 2010, Salt Lake City, Utah Proceedings of the Seed Ecology III Conference Table of Contents Germination Ecology of Dry Sandy Grassland Species along a pH-Gradient Simulated by Different Aluminium Concentrations.....................................................................................................................1 M Abedi, M Bartelheimer, Ralph Krall and Peter Poschlod Induction and Release of Secondary Dormancy under Field Conditions in Bromus tectorum.......................2 PS Allen, SE Meyer, and K Foote Seedling Production for Purposes of Biodiversity Restoration in the Brazilian Cerrado Region Can Be Greatly Enhanced by Seed Pretreatments Derived from Seed Technology......................................................4 S Anese, GCM Soares, ACB Matos, DAB Pinto, EAA da Silva, and HWM Hilhorst -

Decapod Crustacean Grooming: Functional Morphology, Adaptive Value, and Phylogenetic Significance

Decapod crustacean grooming: Functional morphology, adaptive value, and phylogenetic significance N RAYMOND T.BAUER Center for Crustacean Research, University of Southwestern Louisiana, USA ABSTRACT Grooming behavior is well developed in many decapod crustaceans. Antennular grooming by the third maxillipedes is found throughout the Decapoda. Gill cleaning mechanisms are qaite variable: chelipede brushes, setiferous epipods, epipod-setobranch systems. However, microstructure of gill cleaning setae, which are equipped with digitate scale setules, is quite conservative. General body grooming, performed by serrate setal brushes on chelipedes and/or posterior pereiopods, is best developed in decapods at a natant grade of body morphology. Brachyuran crabs exhibit less body grooming and virtually no specialized body grooming structures. It is hypothesized that the fouling pressures for body grooming are more severe in natant than in replant decapods. Epizoic fouling, particularly microbial fouling, and sediment fouling have been shown r I m ans of amputation experiments to produce severe effects on olfactory hairs, gills, and i.icubated embryos within short lime periods. Grooming has been strongly suggested as an important factor in the coevolution of a rhizocephalan parasite and its anomuran host. The behavioral organization of grooming is poorly studied; the nature of stimuli promoting grooming is not understood. Grooming characters may contribute to an understanding of certain aspects of decapod phylogeny. The occurrence of specialized antennal grooming brushes in the Stenopodidea, Caridea, and Dendrobranchiata is probably not due to convergence; alternative hypotheses are proposed to explain the distribution of this grooming character. Gill cleaning and general body grooming characters support a thalassinidean origin of the Anomura; the hypothesis of brachyuran monophyly is supported by the conservative and unique gill-cleaning method of the group. -

Biochemical Systematics and Evolutionary Relationships in the Trichoniscus Pusillus Complex (Crustacea, Isopoda, Oniscidea)

Heredity 79 (1997) 463—472 Received 20 August 1996 Biochemical systematics and evolutionary relationships in the Trichoniscus pusillus complex (Crustacea, Isopoda, Oniscidea) MARINA COBOLLI SBORDONI1, VALERIO KETMAIERff, ELVIRA DE MATTHAEIS & STEFANO TAITI Dipartimento di Scienze Ambienta/i, Università di L 'Aquila, V. Vetoio, Local/ta Coppito-67010-L 'Aqu/la, Dipartimento di Biologia An/male e dell'Uomo, Università di Roma La Sap/enza', V./e de/I'Univers/tà 32- 00185-Rome and §Centro di Studio per/a Faunistica ed Eco/ogia Tropicali CNR, V.Romana 17-50125- Florence, Italy Inorder to clarify taxonomic and phylogenetic relationships among Trichoniscus pusillus (Isopoda, Oniscidea) populations, allozyme variation was studied by means of starch gel electrophoresis. The genetic structure of several populations belonging to different subspecies (diploid bisexual, triploid parthenogenetic; epigean, troglophilic and troglobitic) was assessed by investigating 10 enzymatic systems corresponding to 15 putative loci. F-statistics and cluster- ing analysis indicated a high degree of genetic differentiation, corresponding to low levels of gene flow among populations, both epigean and hypogean, still considered to be conspecific. Estimates of divergence times calculated from genetic distance data suggest that the pattern of differentiation and the colonization of cave environments may be related to the palaeoclimatic change of the Messinian and PIio—Pleistocene glaciations. Keywords: allozymes, cave fauna, divergencetimes, genetic polymorphism, phylogeny, Tricho- niscus pusillus. Introduction accepted, is arbitrary and subjective. Thorpe (1987) stressed that most species in natural circumstances Trichoniscuspusillus Brandt, 1833 (Isopoda, Onisci- may have patterns of geographical variation. As dea) is considered to be a polytypic species, widely conventional subspecies are not natural categories, distributed in the Palaearctic region, whose popula- tions have been arranged in several subspecies. -

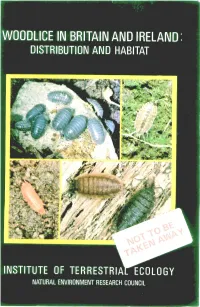

Woodlice in Britain and Ireland: Distribution and Habitat Is out of Date Very Quickly, and That They Will Soon Be Writing the Second Edition

• • • • • • I att,AZ /• •• 21 - • '11 n4I3 - • v., -hi / NT I- r Arty 1 4' I, • • I • A • • • Printed in Great Britain by Lavenham Press NERC Copyright 1985 Published in 1985 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Administrative Headquarters Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton HUNTINGDON PE17 2LS ISBN 0 904282 85 6 COVER ILLUSTRATIONS Top left: Armadillidium depressum Top right: Philoscia muscorum Bottom left: Androniscus dentiger Bottom right: Porcellio scaber (2 colour forms) The photographs are reproduced by kind permission of R E Jones/Frank Lane The Institute of Terrestrial Ecology (ITE) was established in 1973, from the former Nature Conservancy's research stations and staff, joined later by the Institute of Tree Biology and the Culture Centre of Algae and Protozoa. ITE contributes to, and draws upon, the collective knowledge of the 13 sister institutes which make up the Natural Environment Research Council, spanning all the environmental sciences. The Institute studies the factors determining the structure, composition and processes of land and freshwater systems, and of individual plant and animal species. It is developing a sounder scientific basis for predicting and modelling environmental trends arising from natural or man- made change. The results of this research are available to those responsible for the protection, management and wise use of our natural resources. One quarter of ITE's work is research commissioned by customers, such as the Department of Environment, the European Economic Community, the Nature Conservancy Council and the Overseas Development Administration. The remainder is fundamental research supported by NERC. ITE's expertise is widely used by international organizations in overseas projects and programmes of research. -

Characterization of the Dominant Bacterial Communities Associated with Terrestrial Isopod Species Based on 16S Rdna Analysis by PCR-DGGE

Open Journal of Ecology, 2018, 8, 495-509 http://www.scirp.org/journal/oje ISSN Online: 2162-1993 ISSN Print: 2162-1985 Characterization of the Dominant Bacterial Communities Associated with Terrestrial Isopod Species Based on 16S rDNA Analysis by PCR-DGGE Delhoumi Majed, Zaabar Wahiba, Bouslama Mohamed Fadhel, Achouri Mohamed Sghaier* Laboratory of Bio-Ecology and Evolutionary Systematics, Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences of Tunis, University of Tunis El Manar, Tunis, Tunisia How to cite this paper: Majed, D., Wahi- Abstract ba, Z., Fadhel, B.M. and Sghaier, A.M. (2018) Characterization of the Dominant Bacterial From the marine environment, woodlice gradually colonized terrestrial areas Communities Associated with Terrestrial benefiting from the symbiotic relationship with the bacterial community that Isopod Species Based on 16S rDNA Analy- they host. Indeed, they constitute the only group of Oniscidea suborder that sis by PCR-DGGE. Open Journal of Ecolo- gy, 8, 495-509. has succeed to accomplish their lives in terrestrial even desert surfaces. Here- https://doi.org/10.4236/oje.2018.89030 in they play an important role in the dynamic of ecosystems and the decom- position of litter. So to enhance our understanding of the sea-land transition Received: January 30, 2018 and other process like decomposition and digestion of detritus, we studied Accepted: September 15, 2018 Published: September 18, 2018 the bacterial community associated with 11 specimens of terrestrial isopods belonging to six species using a Culture independent approach (DGGE). Copyright © 2018 by authors and Bands sequencing showed that the cosmopolitan species Porcellionides prui- Scientific Research Publishing Inc. nosus has the most microbial diversity. -

Download-The-Data (Accessed on 12 July 2021))

diversity Article Integrative Taxonomy of New Zealand Stenopodidea (Crustacea: Decapoda) with New Species and Records for the Region Kareen E. Schnabel 1,* , Qi Kou 2,3 and Peng Xu 4 1 Coasts and Oceans Centre, National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research, Private Bag 14901 Kilbirnie, Wellington 6241, New Zealand 2 Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China; [email protected] 3 College of Marine Science, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 4 Key Laboratory of Marine Ecosystem Dynamics, Second Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Hangzhou 310012, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +64-4-386-0862 Abstract: The New Zealand fauna of the crustacean infraorder Stenopodidea, the coral and sponge shrimps, is reviewed using both classical taxonomic and molecular tools. In addition to the three species so far recorded in the region, we report Spongicola goyi for the first time, and formally describe three new species of Spongicolidae. Following the morphological review and DNA sequencing of type specimens, we propose the synonymy of Spongiocaris yaldwyni with S. neocaledonensis and review a proposed broad Indo-West Pacific distribution range of Spongicoloides novaezelandiae. New records for the latter at nearly 54◦ South on the Macquarie Ridge provide the southernmost record for stenopodidean shrimp known to date. Citation: Schnabel, K.E.; Kou, Q.; Xu, Keywords: sponge shrimp; coral cleaner shrimp; taxonomy; cytochrome oxidase 1; 16S ribosomal P. Integrative Taxonomy of New RNA; association; southwest Pacific Ocean Zealand Stenopodidea (Crustacea: Decapoda) with New Species and Records for the Region. -

Lack of Taxonomic Differentiation in An

ARTICLE IN PRESS Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution xxx (2005) xxx–xxx www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Lack of taxonomic diVerentiation in an apparently widespread freshwater isopod morphotype (Phreatoicidea: Mesamphisopidae: Mesamphisopus) from South Africa Gavin Gouws a,¤, Barbara A. Stewart b, Conrad A. Matthee a a Evolutionary Genomics Group, Department of Botany and Zoology, University of Stellenbosch, Private Bag X1, Matieland 7602, South Africa b Centre of Excellence in Natural Resource Management, University of Western Australia, 444 Albany Highway, Albany, WA 6330, Australia Received 20 December 2004; revised 2 June 2005; accepted 2 June 2005 Abstract The unambiguous identiWcation of phreatoicidean isopods occurring in the mountainous southwestern region of South Africa is problematic, as the most recent key is based on morphological characters showing continuous variation among two species: Mesam- phisopus abbreviatus and M. depressus. This study uses variation at 12 allozyme loci, phylogenetic analyses of 600 bp of a COI (cyto- chrome c oxidase subunit I) mtDNA fragment and morphometric comparisons to determine whether 15 populations are conspeciWc, and, if not, to elucidate their evolutionary relationships. Molecular evidence suggested that the most easterly population, collected from the Tsitsikamma Forest, was representative of a yet undescribed species. Patterns of diVerentiation and evolutionary relation- ships among the remaining populations were unrelated to geographic proximity or drainage system. Patterns of isolation by distance were also absent. An apparent disparity among the extent of genetic diVerentiation was also revealed by the two molecular marker sets. Mitochondrial sequence divergences among individuals were comparable to currently recognized intraspeciWc divergences. Sur- prisingly, nuclear markers revealed more extensive diVerentiation, more characteristic of interspeciWc divergences. -

Uncorrected Proof

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE + MODEL ARTICLE IN PRESS EJSOBI2173_proof 7 March 2007 1/8 provided by University of Debrecen Electronic Archive 1 53 2 54 3 55 e 4 European Journal of Soil Biology xx (2007) 1 8 56 http://www.elsevier.com/locate/ejsobi 5 57 6 Original article 58 7 59 8 Changes of isopod assemblages along an urbane 60 9 e 61 10 suburban rural gradient in Hungary 62 11 63 12 Elisabeth Hornung a,*,Be´la To´thme´re´sz b, Tibor Magura c, Ferenc Vilisics a 64 13 65 a 14 Department of Ecology, SzIU, FVS, Institute for Zoology, H-1400 Budapest, PO Box 2, Hungary 66 b Ecological Institute, University of Debrecen, Hungary 15 c Hortoba´gy National Park Directorate, Debrecen, Hungary 67 16 68 17 Received 13 December 2005; acceptedPROOF 17 January 2007 69 18 70 19 71 20 72 21 Abstract 73 22 74 23 Responses of isopod assemblages to urbanisation were studied along an urbanesuburbanerural gradient representing a decrease 75 24 in the intensity of human disturbance. Pitfall trapping collected six species (Armadillidium vulgare, Porcellio scaber, Porcellium 76 25 collicola, Trachelipus ratzeburgii, Cylisticus convexus, and Trachelipus rathkii). A. vulgare occurred abundantly in all sites reflect- 77 ing the broad tolerance and invasive nature of this species. Indicator species analysis demonstrated that P. scaber and T. rathkii were 26 78 significant quantitative character species for the urban site, while T. ratzeburgii was characteristic for the natural habitats (suburban 27 and rural sites). -

Common Kansas Spiders

A Pocket Guide to Common Kansas Spiders By Hank Guarisco Photos by Hank Guarisco Funded by Westar Energy Green Team, American Arachnological Society and the Chickadee Checkoff Published by the Friends of the Great Plains Nature Center i Table of Contents Introduction • 2 Arachnophobia • 3 Spider Anatomy • 4 House Spiders • 5 Hunting Spiders • 5 Venomous Spiders • 6-7 Spider Webs • 8-9 Other Arachnids • 9-12 Species accounts • 13 Texas Brown Tarantula • 14 Brown Recluse • 15 Northern Black Widow • 16 Southern & Western Black Widows • 17-18 Woodlouse Spider • 19 Truncated Cellar Spider • 20 Elongated Cellar Spider • 21 Common Cellar Spider • 22 Checkered Cobweb Weaver • 23 Quasi-social Cobweb Spider • 24 Carolina Wolf Spider • 25 Striped Wolf Spider • 26 Dotted Wolf Spider • 27 Western Lance Spider • 28 Common Nurseryweb Spider • 29 Tufted Nurseryweb Spider • 30 Giant Fishing Spider • 31 Six-spotted Fishing Spider • 32 Garden Ghost Spider Cover Photo: Cherokee Star-bellied Orbweaver ii Eastern Funnelweb Spider • 33 Eastern and Western Parson Spiders • 34 Garden Ghost Spider • 35 Bark Crab Spider • 36 Prairie Crab Spider • 37 Texas Crab Spider • 38 Black-banded Crab Spider • 39 Ridge-faced Flower Spider • 40 Striped Lynx Spider • 41 Black-banded Common and Convict Zebra Spiders • 42 Crab Spider Dimorphic Jumping Spider • 43 Bold Jumping Spider • 44 Apache Jumping Spider • 45 Prairie Jumping Spider • 46 Emerald Jumping Spider • 47 Bark Jumping Spider • 48 Puritan Pirate Spider • 49 Eastern and Four-lined Pirate Spiders • 50 Orchard Spider • 51 Castleback Orbweaver • 52 Triangulate Orbweaver • 53 Common & Cherokee Star-bellied Orbweavers • 54 Black & Yellow Garden Spider • 55 Banded Garden Spider • 56 Marbled Orbweaver • 57 Eastern Arboreal Orbweaver • 58 Western Arboreal Orbweaver • 59 Furrow Orbweaver • 60 Eastern Labyrinth Orbweaver • 61 Giant Long-jawed Orbweaver • 62 Silver Long-jawed Orbweaver • 63 Bowl and Doily Spider • 64 Filmy Dome Spider • 66 References • 67 Pocket Guides • 68-69 1 Introduction This is a guide to the most common spiders found in Kansas. -

An Evolutionary Solution of Terrestrial Isopods to Cope with Low

© 2017. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2017) 220, 1563-1567 doi:10.1242/jeb.156661 SHORT COMMUNICATION An evolutionary solution of terrestrial isopods to cope with low atmospheric oxygen levels Terézia Horváthová*, Andrzej Antoł, Marcin Czarnoleski, Jan Kozłowski and Ulf Bauchinger ABSTRACT alternatively represent secondary adaptations to meet changing The evolution of current terrestrial life was founded by major waves of oxygen requirements in organisms subject to environmental land invasion coinciding with high atmospheric oxygen content. change. These waves were followed by periods with substantially reduced Here, we show that catch-up growth is probably a further example oxygen concentration and accompanied by the evolution of novel of such an evolutionary innovation. Switching from aquatic to air traits. Reproduction and development are limiting factors for conditions during development within the motherly brood pouch of Porcellio scaber evolutionary water–land transitions, and brood care has probably the terrestrial isopod relaxes oxygen limitations facilitated land invasion. Peracarid crustaceans provide parental care and facilitates accelerated growth under motherly protection. Our for their offspring by brooding the early stages within the motherly findings provide important insights into the role of oxygen in brood brood pouch, the marsupium. Terrestrial isopod progeny begin care in present-day terrestrial crustaceans. ontogenetic development within the marsupium in water, but conclude development within the marsupium in air. Our results for MATERIALS AND METHODS progeny growth until hatching from the marsupium provide evidence Experimental animals for the limiting effects of oxygen concentration and for a potentially Early development in terrestrial isopods occurs sequentially in adaptive solution.