FACILITATING a SAFE and RESPECTFUL WORKPLACE 2 Facilitating a Safe and Respectful Workplace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telecommuting Pluses & Pitfalls

Telecommuting Pluses & Pitfalls Brenda B. Thompson Attorney M. LEE SMITH PUBLISHERS LLC Brentwood, Tennessee This special report provides practical information concerning the subject matters covered. It is sold with the understanding that neither the publisher nor the writer is rendering legal advice or other professional service. Some of the information provided in this special report contains a broad overview of federal law. The law changes regularly, and the law may vary from state to state and from one locality to another.You should consult a competent attorney in your state if you are in need of specific legal advice concerning any of the subjects addressed in this special report. © 1996, 1999 M. Lee Smith Publishers LLC 5201 Virginia Way P.O. Box 5094 Brentwood,Tennessee 37024-5094 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Thompson, Brenda B. Telecommuting pluses & pitfalls / Brenda B.Thompson. p. cm. ISBN 0-925773-30-1 (coil binding) 1.Telecommunication — Social aspects — United States. 2.Telecommunication policy — United States. 3. Information technology — Social aspects — United States. I.Title. HE7775.T47 1996 96-21827 658.3'128 — dc20 CIPiw Printed in the United States of America Contents INTRODUCTION ....... 1 1 — THE TELECOMMUTING TREND....... 3 Types of Telecommuting....... 3 The Benefits of Telecommuting....... 4 A Sampling of Current Telecommuting Programs....... 5 To Telecommute or Not to Telecommute....... 7 2 — DECIDING WHO WILL TELECOMMUTE....... 9 Selecting Employees....... 9 Dealing with a Union...... -

Nightmares, Demons and Slaves

Management Communication Quarterly Volume 20 Number 2 November 2006 1-38 Nightmares, Demons © 2006 Sage Publications 10.1177/0893318906291980 http://mcq.sagepub.com and Slaves hosted at Exploring the Painful Metaphors http://online.sagepub.com of Workplace Bullying Sarah J. Tracy Arizona State University, Tempe Pamela Lutgen-Sandvik University of New Mexico, Albuquerque Jess K. Alberts Arizona State University, Tempe Although considerable research has linked workplace bullying with psy- chosocial and physical costs, the stories and conceptualizations of mistreat- ment by those targeted are largely untold. This study uses metaphor analysis to articulate and explore the emotional pain of workplace bullying and, in doing so, helps to translate its devastation and encourage change. Based on qualitative data gathered from focus groups, narrative interviews and target drawings, the analysis describes how bullying can feel like a battle, water tor- ture, nightmare, or noxious substance. Abused workers frame bullies as nar- cissistic dictators, two-faced actors, and devil figures. Employees targeted with workplace bullying liken themselves to vulnerable children, slaves, pris- oners, animals, and heartbroken lovers. These metaphors highlight and delimit possibilities for agency and action. Furthermore, they may serve as diagnostic cues, providing shorthand necessary for early intervention. Keywords: workplace bullying; emotion; metaphor analysis; work feelings; harassment So many people have told me, “Oh, just let it go. Just let it go.” What’s inter- esting is people really don’t understand or comprehend the depths of the bully’s evilness until it’s done to them. Then they’re shocked. I had people Authors’ Note: We thank the College of Public Programs and the Office of the Vice President for Research and Economic Affairs at Arizona State University for a grant that helped fund this research. -

Workplace Harassment And/Or Discrimination

Section 10.04 Complaints of Unlawful Workplace Harassment and/or Discrimination I. PURPOSE a. To establish procedures for the reporting and investigation of discriminatory incidents in the workplace; to emphasize that discrimination, harassment, and retaliation will not be tolerated in the workplace. II. REFERENCE a. Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967, as amended (ADEA), 29 U.S.C.’621 et seq. b. Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, as amended (ADA), 42 U.S.C. ‘12111 et seq. c. Code of Federal Regulations Title 29, Part 1605.1 d. Pregnancy Discrimination Act (PDA) e. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended (Title VII), 42 U.S.C. ‘2000e et seq. f. Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act of 1994 (USERRA), 38 U.S.C. ‘4301 et seq. III. GENERAL It is the policy of Burke County to comply with all applicable federal and state laws, rules, regulations, and guidelines regarding employment discrimination and retaliation. Discrimination or harassment against employees and applicants due to race, color, religion, sex, gender identity, national origin, disability, age, or military status is illegal. It is unlawful for any person to discriminate in any manner against any other person because that person has opposed any unlawful discrimination practice. It is also unlawful to retaliate against any person who has made a charge of employment discrimination, testified, assisted or participated in any manner in an investigation, proceeding, or hearing. Burke County encourages all employees to assist in the effort to achieve equal opportunity in the workplace. Violations of this policy may be cause for disciplinary action, including termination. -

Down Top Workplace Incivility and Organizational Health of Deposit Money Banks in Nigeria

International Journal of Business and Management Review Vol.7, No.5, pp.61-84, August 2019 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) DOWN TOP WORKPLACE INCIVILITY AND ORGANIZATIONAL HEALTH OF DEPOSIT MONEY BANKS IN NIGERIA Dr. L.I. Nwaeke Department of Management m Rivers State University, Port-Harcourt Akani, Vivian Chinogounum Postgraduate Student, Department of Management, Rivers State University Port-Harcourt ABSTRACT: This study examined the effects of down top workplace incivility on organizational health of deposit money banks in Rivers State. The objective was to investigate the nature of relationship between down top workplace incivility and organizational health. The independent variable proxy was down top workplace incivility while organizational health proxy was goal focus, resource utilization and cohesiveness. This study explored quasi-experimental research design. The population of the study comprises of 17 deposit money banks operating in Port Harcourt quoted in the Nigeria Stock Exchange. Three hundred and forty six respondents were obtained as sample size, using the Taro Yemen’s formula. Spearman rank correlation was used to test the null hypotheses at 0.05 level of significance computed within SPSS software. The study found that there negative and no significant relationship between down top workplace incivility and resource utilization, negative and no significant relationship between down top workplace incivility and cohesiveness. Furthermore, the study also revealed a negative and no significance relationship between down top incivility and goal focus. The findings of this study support the need to appraise organizational incivility, especially among high-status employees, as perceived across all hierarchical levels considering the significant relationships between structure and workplace incivility and organizational health. -

A Theory of Biobehavioral Response to Workplace Incivility

BIOBEHAVIORAL RESPONSE TO INCIVILITY THE EMBODIMENT OF INSULT: A THEORY OF BIOBEHAVIORAL RESPONSE TO WORKPLACE INCIVILITY Lilia M. Cortina University of Michigan 530 Church Street Ann Arbor, MI 48104 [email protected] M. Sandy Hershcovis University of Calgary 2500 University Drive NW Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 [email protected] Kathryn B.H. Clancy University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 607 S. Mathews Ave. Urbana, IL 61801 [email protected] (in press, Journal of Management) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors are grateful to Christine Porath, who provided feedback on an earlier draft of this article. Hershcovis acknowledges support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Clancy acknowledges support from NSF grant #1916599, the Illinois Leadership Center, and the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science & Technology, and thanks her trainees as well as the attendees of the 2019 Transdisciplinary Research on Incivility in STEM Contexts Workshop for their brilliant thinking and important provocations. BIOBEHAVIORAL RESPONSE TO INCIVILITY 1 Abstract This article builds a broad theory to explain how people respond, both biologically and behaviorally, when targeted with incivility in organizations. Central to our theorizing is a multifaceted framework that yields four quadrants of target response: reciprocation, retreat, relationship repair, and recruitment of support. We advance the novel argument that these behaviors not only stem from biological change within the body, but also stimulate such change. Behavioral responses that revolve around affiliation, and produce positive social connections, are most likely to bring biological benefits. However, social and cultural features of an organization can stand in the way of affiliation, especially for employees holding marginalized identities. -

Employee Onboarding

Strategic Onboarding: The Effects on Productivity, Engagement, & Turnover By: Lisa Reed, MBA, SPHR Onboarding Defined A systematic and comprehensive approach to integrating a new employee with an employer and its culture, while also ensuring the employee is provided with the tools and information necessary to becoming a productive member of the team (1). How Important is Onboarding? 43% of employees state the opportunity for advancement was the key factor in deciding whether or not to stay with an organization, and the onboarding process, or lack thereof, was a main factor in determining advancement potential within a company (2). EMPLOYEE PRODUCTIVITY What is Employee Productivity? An assessment of the efficiency of a worker or group of workers, which is typically compared to averages, is referred to as employee productivity (3). Costs of Employee Unproductivity More than $37 billion dollars annually is spent by organizations in the US to keep unproductive employee in jobs they do not understand (4). What Effect Does Strategic Onboarding Have On Employee Productivity? Only 49% of new employees without formal onboarding meet their first performance milestone (5). In contrast, 77% of employees who are provided with a formal onboarding process meet first performance milestones (6). Employee performance can increase by 11% with an effective onboarding process, which can also be linked to a 20% increase in an employee’s discretionary effort (7). EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT What is Employee Engagement? Employee engagement describes the way employees show a logical and emotional commitment to their work, team, and organization, which in turn drives their discretionary effort. Costs of Employee Disengagement Actively disengaged employees are more likely to steal, miss work, and negatively influence other workers and cost the United States up to $550 billion annually in lost resources and productivity (8). -

Data Sheet: Oracle Recruiting Cloud

Oracle Recruiting Finding the best talent, hiring them quickly and onboarding them efficiently, can be difficult in today’s competitive environment. Oracle Recruiting (part of Oracle Cloud HCM) addresses these common challenges of recruiting and takes this process into the modern era by leveraging a data-driven approach and a mobile user interface (UI) to Key features source and engage both internal and external • Requisition management • Career page design templates candidates, and apply business insights across • Mobile-responsive UI all of HCM for better hiring decisions. • Extensible branding and multimedia support • Job search and discovery INNOVATIVE TECHNOLOGY TO KEEP CANDIDATES AT • Candidate pools THE CENTER OF THE RECRUITING PROCESS • Adaptive intelligence Savvy organizations use technology to stay ahead of the competition when it comes • Native recruiting to attracting and retaining top talent. HR leaders are being tasked with broadening • End-to-end sourcing, recruiting, their approach to Human Capital Management, incorporating concepts and practices and offers that were once the primary domain of marketing, legal, or chief executives. The • Unified architecture and tooling practice of HR is also transforming from being a mere cost center to a value • Multichannel sourcing generator, driving business growth through holistic talent development. HR is evolving to increasingly leverage technology to improve efficiency and provide • Conversational interactions via insight into an organization’s most valuable source of productivity. Organizations use digital assistant this insight to help leaders understand success parameters and their organization’s • Proven third-party extensions talent capabilities. • Advanced reporting and analytics Oracle Recruiting is a new recruiting solution delivered natively as part of Oracle • Unified self-service interface Cloud HCM. -

Violence Free Workplace Policy No

Sub Topic: Violence Free Workplace Policy No. 13-03 Topic: Health & Safety Employees Covered: All Employees Section: Human Resources Council Adoption Date: June 21, 2010 Effective Date: June 15, 2010 Revision No: 001 Date: July 1, 2016 CAO Approval: Date: Policy Statement & Strategic Plan Linkages The Corporation of the Town of Newmarket is committed to ensuring that all employees feel safe and secure at all times within the workplace. Maintaining a workplace that is free from violence is a responsibility of all employees as part of the health and safety Internal Responsibility System. The Town will not tolerate, ignore, or condone workplace violence and considers violence to be a serious offence. The Town policy emphasizes education, risk management, prevention and zero-tolerance for workplace violence. All employees are expected to work in a safe and respectful manner and uphold this policy as workplace violence is unacceptable at the Town of Newmarket. Purpose The purpose of this policy is to demonstrate the Town’s commitment to the Occupational Health & Safety Act by protecting employees from sources of workplace violence; to define the duties and responsibilities of the employer and employees in supporting this policy; and to address all incidents or complaints of workplace violence. The Town’s violence free workplace strategy of prevention and elimination includes a policy, program, employee instruction and hazard recognition processes. Definitions: "Workplace Violence" - Is defined as: (a) the exercise of physical force by a person against a worker, in a workplace, that causes or could cause physical injury to the worker, (b) an attempt to exercise physical force against a worker, in a workplace, that could cause physical injury to the worker, (c) a statement or behaviour that it is reasonable for a worker to interpret as a threat to exercise physical force against the worker, in a workplace, that could cause physical injury to the worker. -

Taking the First Step: Workplace Responses to Domestic and Family Violence December 2017 Nationaltable of Contents Domestic Violence Survey Respondents

Taking the first step: Workplace responses to domestic and family violence December 2017 NationalTable of contents Domestic Violence Survey Respondents Foreword 1 Executive summary 5 Introduction 8 Australian Case Studies 17 Aurizon 17 Australia Post 18 Australian Public Service 20 Autopia 21 Carlton Football Club 22 Commonwealth Bank 24 Housing Plus 25 Konica Minolta 28 Mirvac Group 29 PwC Australia 31 Queensland Government 33 Rio Tinto 35 Telstra 38 Conclusion 40 Acknowledgements 41 If you or someone you know has experienced domestic or family violence, phone 1800 RESPECT, or visit www.1800respect.org.au B | Taking the first step: Workplace responses to domestic and family violence Taking the first step: Workplace responses to domestic and family violence Foreword Violence against women is one of the most workplace and contributes to sex discrimination serious, life threatening and widespread violations at work. Data show that women who are exposed of human rights globally. In Australia, 40.8% of to intimate partner violence are employed in women have experienced some form of violence higher numbers in casual and part-time work, since the age of 15.1 Violence against women and that their earnings from formal wage work occurs in the home, in public spaces and also are 60% lower, compared to women who do not in the workplace. Across Asia, studies in Japan, experience such violence.4 Malaysia, the Philippines and the Republic of Korea show that 30 to 40% of women suffer workplace Violence against women also carries with it sexual harassment.2 Workplaces are affected significant costs, to individuals, businesses and by violence in the workplace and by family and societies. -

Leading Remote Teams Provided By: Taggart Insurance

Leading Remote Teams Provided by: Taggart Insurance This HR Toolkit is not intended to be exhaustive nor should any discussion or opinions be construed as legal advice. Readers should contact legal counsel for legal advice. © 2020 Zywave, Inc. All rights reserved. Leading Remote Teams | Provided by: Taggart Insurance Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................4 Remote Work Planning ................................................................................................5 Schedules .....................................................................................................5 Technology ....................................................................................................5 Employee Workstation ..................................................................................5 Policies ..........................................................................................................6 Interviewing and Onboarding .......................................................................6 Virtual Interviewing ................................................................6 Remote Onboarding ..............................................................7 Company Culture in the Remote Workplace ...............................................................9 What Is Company Culture? ..........................................................................9 Strong Company Culture.............................................................................. -

New Employee Onboarding Checklist

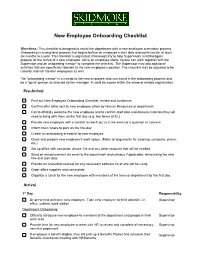

New Employee Onboarding Checklist Directions: This checklist is designed to assist the department with a new employee orientation process. Onboarding is a long-term process that begins before an employee’s start date and continues for at least six months to a year. This checklist is organized chronologically to help Supervisors and Managers prepare for the arrival of a new employee. Once an employee starts, he/she can work together with the Supervisor and an onboarding mentor* to complete the checklist. The Supervisor may add additional activities that are specifically relevant to the new employee’s position. The checklist may be adjusted to be used for internal transfer employees as well. *An "onboarding mentor" is a mentor to the new employee who can assist in the onboarding process and be a “go-to” person as directed by the manager. It could be a peer within the same or related organization. Pre-Arrival Print out New Employee Onboarding Checklist, review and customize Confirm offer letter sent to new employee either by Human Resources or department Call to officially welcome the new employee and to confirm start date and discuss materials they will need to bring with them on the first day (e.g. two forms of ID.) Provide new employee with a contact to reach out to in the event of a question or concern Inform them where to park on the first day Create an onboarding schedule for new employee Clean and prepare new employee's work space. (Make arrangements for cleaning, computer, phone, etc.) Set up office with computer, phone, file and any other resource that will be needed Send an announcement via email to the department and campus if applicable, announcing the new hire and start date Provide an instruction manual for any necessary software he or she will be using Order office supplies and name plate Organize a lunch for the new employee with members of the team or department for the first day Arrival 1st Day Responsibility Be present to welcome new employee. -

Workplace Harassment Prevention Toolkit: (Your Guide to Preventing and Identifying Harassment in the Workplace)

Employee Workplace Harassment Prevention Toolkit: (Your guide to preventing and identifying harassment in the workplace) Question: Answer: What is harassment? Unwelcome verbal or physical conduct that denigrates, shows hostility or aversion toward an individual based on any characteristic protected by law, which includes race, color, religion, sex (including gender identity and pregnancy), national origin, age (40 and older), disability, genetic information, sexual orientation, parental status, marital status, political affiliation, military service, or retaliation. What constitutes the Anti-discrimination laws prohibit harassment of an basis of retaliation individual in retaliation against an employee who has: filed when alleging a discrimination complaint, testified, assisted or harassment? participated in any manner in an investigation, proceeding, hearing or litigation under governing EEOC statutes, oppose employment practices they believe to discriminate, or requested a reasonable accommodation. What is unlawful Harassment becomes unlawful where harassment? 1) Enduring the offensive conduct becomes a condition of continued employment, or 2) The conduct is severe or pervasive enough to create a work environment that a reasonable person would consider intimidating, hostile, or abusive. What are the two basic Quid Pro Quo Harassment- “This for That” types of unlawful And harassment? Hostile Work Environment Harassment What is Quid Pro Quo Quid Pro Quo harassment occurs when a tangible Harassment? employment action is made based on the employee’s submission to or rejection of unwelcome conduct. This kind of harassment is generally committed by a supervisor or someone who can make or recommend formal employment decisions that will affect the victim. What is a tangible A tangible employment action involves a significant change employment action? in status, e.g., change in pay, work status, dismissal, demotion, hire, failure to promote, transfer, undesirable reassignment, and work assignments.