Devotion to the Holy Cross and a Dislocated Mass-Text Gerald Ellard, Sj

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020-11-01 Gregorian Chant, Preliminary

All Souls’ Day (Transferred from November 2) Sunday, November 1, 2020, 5:00 p.m. ALL SOULS’ DAY/ALL SOULS’ REQUIEM The tradition of observing November 2 as a day of commemoration began in the tenth century as a complement to All Saints’ Day, November 1. The traditional service of remembering the dead — whether on this day or during an actual funeral — is called a Requiem, the first word of the Latin text, meaning “rest.” The solemnity of the liturgy and the beauty of the music help us to mourn with hope. Thus we are encouraged to trust ever more in God’s gift of eternal life through the death and resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ. THE GREGORIAN CHANT REQUIEM The oldest musical setting of the Requiem is the version in Gregorian Chant (plainsong, melody only, no harmony). Created sometime in the first millennium A.D., it does have one “new” movement, the Dies irae, dating from no later than the 1200s. The Dies irae melody has been quoted in non-Requiem music by Hector Berlioz, Franz Liszt, Sergei Rachmaninoff, and Camille Saint-Saëns, among others. Some composers of Requiem settings have omitted the Dies irae text, either because of its length or because of its expression of fear, guilt, and judgment. Regarding the latter issue, Jesus, his apostles, and his Hebrew prophets do indeed declare a day of reckoning, and fear is a legitimate human feeling, expressed in the Psalms and in the Prophets. However, God’s grace can ease our fear, and — through the Holy Spirit’s ministry — can offset it by giving us confidence in Christ’s merit rather than our own. -

Introitus: the Entrance Chant of the Mass in the Roman Rite

Introitus: The Entrance Chant of the mass in the Roman Rite The Introit (introitus in Latin) is the proper chant which begins the Roman rite Mass. There is a unique introit with its own proper text for each Sunday and feast day of the Roman liturgy. The introit is essentially an antiphon or refrain sung by a choir, with psalm verses sung by one or more cantors or by the entire choir. Like all Gregorian chant, the introit is in Latin, sung in unison, and with texts from the Bible, predominantly from the Psalter. The introits are found in the chant book with all the Mass propers, the Graduale Romanum, which was published in 1974 for the liturgy as reformed by the Second Vatican Council. (Nearly all the introit chants are in the same place as before the reform.) Some other chant genres (e.g. the gradual) are formulaic, but the introits are not. Rather, each introit antiphon is a very unique composition with its own character. Tradition has claimed that Pope St. Gregory the Great (d.604) ordered and arranged all the chant propers, and Gregorian chant takes its very name from the great pope. But it seems likely that the proper antiphons including the introit were selected and set a bit later in the seventh century under one of Gregory’s successors. They were sung for papal liturgies by the pope’s choir, which consisted of deacons and choirboys. The melodies then spread from Rome northward throughout Europe by musical missionaries who knew all the melodies for the entire church year by heart. -

Understanding When to Kneel, Sit and Stand at a Traditional Latin Mass

UNDERSTANDING WHEN TO KNEEL, SIT AND STAND AT A TRADITIONAL LATIN MASS __________________________ A Short Essay on Mass Postures __________________________ by Richard Friend I. Introduction A Catholic assisting at a Traditional Latin Mass for the first time will most likely experience bewilderment and confusion as to when to kneel, sit and stand, for the postures that people observe at Traditional Latin Masses are so different from what he is accustomed to. To understand what people should really be doing at Mass is not always determinable from what people remember or from what people are presently doing. What is needed is an understanding of the nature of the liturgy itself, and then to act accordingly. When I began assisting at Traditional Latin Masses for the first time as an adult, I remember being utterly confused with Mass postures. People followed one order of postures for Low Mass, and a different one for Sung Mass. I recall my oldest son, then a small boy, being thoroughly amused with the frequent changes in people’s postures during Sung Mass, when we would go in rather short order from standing for the entrance procession, kneeling for the preparatory prayers, standing for the Gloria, sitting when the priest sat, rising again when he rose, sitting for the epistle, gradual, alleluia, standing for the Gospel, sitting for the epistle in English, rising for the Gospel in English, sitting for the sermon, rising for the Credo, genuflecting together with the priest, sitting when the priest sat while the choir sang the Credo, kneeling when the choir reached Et incarnatus est etc. -

Low Requiem Mass

REQUIEM LOW MASS FOR TWO SERVERS The Requiem Mass is very ancient in its origin, being the predecessor of the current Roman Rite (i.e., the so- called “Tridentine Rite”) of Mass before the majority of the gallicanizations1 of the Mass were introduced. And so, many ancient features, in the form of omissions from the normal customs of Low Mass, are observed2. A. Interwoven into the beautiful and spiritually consoling Requiem Rite is the liturgical principle, that all blessings are reserved for the deceased soul(s) for whose repose the Mass is being celebrated. This principle is put into action through the omission of these blessings: 1. Holy water is not taken before processing into the Sanctuary. 2. The sign of the Cross is not made at the beginning of the Introit3. 3. C does not kiss the praeconium4 of the Gospel after reading it5. 4. During the Offertory, the water is not blessed before being mixed with the wine in the chalice6. 5. The Last Blessing is not given. B. All solita oscula that the servers usually perform are omitted, namely: . When giving and receiving the biretta. When presenting and receiving the cruets at the Offertory. C. Also absent from the Requiem Mass are all Gloria Patris, namely during the Introit and the Lavabo. D. The Preparatory Prayers are said in an abbreviated form: . The entire of Psalm 42 (Judica me) is omitted; consequently the prayers begin with the sign of the Cross and then “Adjutorium nostrum…” is immediately said. After this, the remainder of the Preparatory Prayers are said as usual. -

The Epistle Revelation 21:1-6A

The Feast of All Saints, Year B The Epistle Revelation 21:1-6a START HERE A Reading from the Book of Revelation. saw a new heaven and a new earth; will be with them; he will wipe every Ifor the first heaven and the first tear from their eyes. Death will be no earth had passed away, and the sea was more; mourning and crying and pain no more. And I saw the holy city, the will be no more, for the first things new Jerusalem, coming down out of have passed away.” And the one who heaven from God, prepared as a bride was seated on the throne said, “See, I adorned for her husband. And I heard a am making all things new.” Also he loud voice from the throne saying, “See, said, “Write this, for these words are the home of God is among mortals. He trustworthy and true.” Then he said to will dwell with them as their God; they me, “It is done! I am the Alpha and the will be his peoples, and God himself Omega, the beginning and the end.” Allow for a brief silence, then say: The Word of the Lord. Revised Common Lectionary NRSV Translation The Feast of All Saints, Year B The Psalm Psalm 24 START HERE Please join me in reading verses from Psalm 24 responsively by half verse. 1 The earth is the Lord’s and all that is in it, * the world and all who dwell therein. 2 For it is he who founded it upon the seas * and made it firm upon the rivers of the deep. -

Pdf • an American Requiem

An American Requiem Our nation’s first cathedral in Baltimore An American Expression of our Roman Rite A Funeral Guide for helping Catholic pastors, choirmasters and families in America honor our beloved dead An American Requiem: AN American expression of our Roman Rite Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord, And let perpetual light shine upon them. And may the souls of all the faithful departed, through the mercy of God, Rest in Peace. Amen. Grave of Father Thomas Merton at Gethsemane, Kentucky "This is what I think about the Latin and the chant: they are masterpieces, which offer us an irreplaceable monastic and Christian experience. They have a force, an energy, a depth without equal … As you know, I have many friends in the world who are artists, poets, authors, editors, etc. Now they are well able to appre- ciate our chant and even our Latin. But they are all, without exception, scandalized and grieved when I tell them that probably this Office, this Mass will no longer be here in ten years. And that is the worst. The monks cannot understand this treasure they possess, and they throw it out to look for something else, when seculars, who for the most part are not even Christians, are able to love this incomparable art." — Thomas Merton wrote this in a letter to Dom Ignace Gillet, who was the Abbot General of the Cistercians of the Strict Observance (1964) An American Requiem: AN American expression of our Roman Rite Requiescat in Pace Praying for the Dead The Carrols were among the early founders of Maryland, but as Catholic subjects to the Eng- lish Crown they were unable to participate in the political life of the colony. -

Volume 93, Summer 1966

Volume 93, Summer 1966 Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America Offices of publication at Saint Vincent Arcfiabbey, Latrobe, Pennsylvania 15650 Continuation of: CAECILIA, published by the St. Caecilia Society since 1874 and THE CATHOLIC CHoiRMASTER, published by the St. Gregory Society since 1915. EDITORIAL BOARD Rt. Rev. Rembert G. Weakland, O.S.B., Chairman Mother C. A. Carroll, R.S.C.J., Music review editor Louise Cuyler, Book review editor Rev. Richard J. Schuler, News editor Rev. Ignatius J. Purta, O.S.B., Managing editor Frank D. Szynskie, Circulation Rev. Lawrence Heiman, C.PP.S. Rev. C. J. McNaspy, S.J. Very Rev. Francis P. Schmitt J. Vincent Higginson Rev. Peter D. Nugent Editorial correspondence may be sent to : SACRED MUSIC, SAINT VINCENT ARCHABBEY, LATROBE, PENNSYLVANIA 15650 CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA EXEcUTIVE BoARD Rt. Rev. Rembert G. Weakland, O.S.B., President Rev. Cletus Madsen, Vice-president Rev. Richard J. Schuler, General Secretary Frank D. Szynskie, Treasurer Cecilia Kenny, Regional Chairman, East Coast Rev. Robert Skeris, Regional Chairman, Middle West Roger Wagner, Regional Chairman, West Coast Rev. Joseph R. Foley, C.S.P. Mother Josephine Morgan, R.S.C.J. Rev. John C. Selner, S.S. J. Vincent Higginson Very Rev. Francis P. Schmitt Sister M. Theophane, O.S.F. Memberships in the CMAA include a subscription to SACRED MUSIC. Voting membership, $10.00 annually; by subscription only, $5.00; student membership, $4.00. Application forms for voting and student memberships must be obtained frdm• Sister M. Theophane, O.S.F., Chairman, Membership Committee, CMAA, 3401 South 39th Street, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53215. -

A Conductor's Guide to the Da Vinci Requiem by Cecilia Mcdowall

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2020 A Conductor’s Guide to the Da Vinci Requiem by Cecilia McDowall Jantsen Blake Touchstone Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Touchstone, J. B.(2020). A Conductor’s Guide to the Da Vinci Requiem by Cecilia McDowall. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5920 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S GUIDE TO THE DA VINCI REQUIEM BY CECILIA MCDOWALL by Jantsen Blake Touchstone BaChelor of MusiC Mississippi College, 2011 BaChelor of MusiC Education Mississippi College, 2013 Master of MusiC Mississippi College, 2013 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of MusiCal Arts in Conducting SChool of MusiC University of South Carolina 2020 ACCepted by: AliCia W. Walker, Major Professor Jabarie Glass, Committee Member Andrew Gowan, Committee Member J. Daniel Jenkins, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, ViCe Provost and Dean of the Graduate SChool © Copyright by Jantsen Blake Touchstone, 2020 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION To my wife, Amy Touchstone, for your endless support, patience, love, and saCrifiCe. Your support, patience and understanding have allowed me to complete this projeCt; I thank you. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would begin by thanking CeCilia MCDowall for writing such wonderful choral musiC and allowing such aCCess to her life and thoughts. -

LITURGICAL DEVELOPMENT of the MASS-Ill

LITURGICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE MASS-Ill ALEXIUS SIMONES, O.P. FTER the Credo, the catechumens having been dismissed, the root of the service-the repetition of what Our Lord did at the Last Supper-begins. Our Lord took bread and · wine. So bread and wine must first be brought to the cele brant and placed before him on the altar. St. Justin says that "bread and a cup of wine are brought to the president of the brethren." Originally at this point the people brought up bread and wine which were received by the deacon and placed on the credence table. How ever, in the Eastern rites and in the Gallican rite a later practice of preparing the bread and wine before the beginning of the Mass grew up. Rome alone kept the original practice of offering them at this point, when they are about to be consecrated. In the Middle Ages, as the public presentation of the gifts by the people had disappeared, there seemed to be a void. This interval was fi lled up by our present offertory prayers. But even before the disappearance of this public presentation, the choir sang merely to fill up the time while the sil ent action of offering the gifts proceeded. The offertory chant is of great antiquity. Like the Introit and Communion chants, this chant was always an entire psalm in the early ages. By the time of the first Roman Ordo, the psalm was re duced to an antiphon with one or two verses of the psalm. In the Gregorian Antiphonary it is still the same. -

Worship Aids for the Revised Common Lectionary Advent 2015 Through Reign of Christ 2016

Worship Aids for the Revised Common Lectionary Advent 2015 through Reign of Christ 2016 Year C Paul Soupiset Introduction to Lectionary Aids Year C (2015–2016) David Gambrell Great Resources at Your Fingertips • Prayers after Communion or more than fifty years, Call to Worship: • Blessings and Charges Liturgy, Music, Preaching, and the Arts, a • Seasonal Hymn and Song Suggestions quarterly journal of the Presbyterian Church Again, for tips on using these materials in your F congregation, I encourage you to read the expanded (U.S.A.) Office of Theology and Worship and Presbyterian Association of Musicians, has offered introductions that follow. insight and inspiration for pastors, church musicians, The impulse behind this distinctive combination artists, and other worship leaders. With revised of Sunday/festival and seasonal resources comes and expanded features in the Lectionary Aids and from the conviction that worshipers need a mixture thematic issues, now there’s even more to love. of “new” and “given” information in each service. For each Sunday and festival of the Christian Some elements of worship must change from week year, this Lectionary Aids issue of Call to Worship to week; these elements bring a sharp focus on a (49.1) provides: particular set of scriptural texts or themes for the • Lectionary Summaries day, emphasizing particular aspects of Christian faith • Calls to Worship and life. Other elements of worship should repeat • Prayers of the Day for a period of weeks; these elements work in a • Prayers of Confession cumulative way, immersing worshipers in central • Prayers of the People things and enabling their deeper participation in the • Eucharistic Prayers liturgy. -

Requiem for the Black Children of God

Requiem for the Black Children of God August 1, 2020 Cathedral of St. Thomas More Most Reverend Michael F. Burbidge Presider and Homilist INTRODUCTORY RITES Opening Hymn Come By Here, My Lord Sign of the Cross and Greeting In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. R. Amen. Peace be with you. R. And with your spirit. Penitential Act Brothers and sisters, for too long, too many of us have stood silent or said too little as our Black brothers and sisters and others of God’s family suffer from the systematic racism and its scars in our nation, our communities, and our churches. Let us now acknowledge our sins: I confess to almighty God and to you, my brothers and sisters, that I have greatly sinned, in my thoughts and in my words, in what I have done and in what I have failed to do, They strike their breasts and a bell is rung as they continue: through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault; therefore I ask blessed Mary ever-Virgin, all the Angels and Saints, and you, my brothers and sisters, to pray to me to the Lord our God. May almighty God have mercy on us, forgive us our sins, and bring us to everlasting life. R. Amen. Collect from Mass for Reconciliation, Various Needs 16 Let us pray. O God, author of true freedom, whose will it is to shape all men and women into a single people released from slavery, grant to your Church, we pray, that, as she receives new growth in freedom, she may appear more clearly to the world as the universal sacrament of salvation, manifesting and making present the mystery of your love for all. -

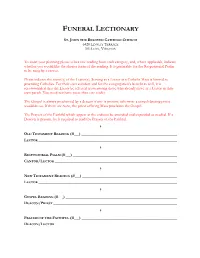

Funeral Lectionary

FUNERAL LECTIONARY ST. JOHN THE BELOVED CATHOLIC CHURCH 6420 LINWAY TERRACE MCLEAN, VIRGINIA To assist your planning please select one reading from each category, and, where applicable, indicate whether you would like the shorter form of the reading. It is preferable for the Responsorial Psalm to be sung by a cantor. Please indicate the name(s) of the Lector(s). Serving as a Lector at a Catholic Mass is limited to practicing Catholics. For their own comfort and for the congregation’s benefit as well, it is recommended that the Lector be selected from among those who already serve as a Lector in their own parish. You need not have more than one reader. The Gospel is always proclaimed by a deacon if one is present, otherwise a concelebrating priest would do so. If there are none, the priest offering Mass proclaims the Gospel. The Prayers of the Faithful which appear at the end can be amended and expanded as needed. If a Deacon is present, he is required to read the Prayers of the Faithful. † OLD TESTAMENT READING (# ) LECTOR † RESPONSORIAL PSALM (# ) CANTOR/LECTOR † NEW TESTAMENT READING (# ) LECTOR † GOSPEL READING (# ) DEACON/PRIEST † PRAYERS OF THE FAITHFUL (# ) DEACON/LECTOR Please choose from among the following approved readings. During the Easter Season, the first reading comes from the Acts of the Apostles or The Book of Revelation from New Testament (Readings 1, 17, 18, or 19 in the “Reading II” section) instead of one of the readings from the Old Testament. Reading I from the OT Reading II from the NT 1.