SAMSON CREE NATION CUMULATIVE EFFECTS ASSESSMENT Updated Analysis for Selected Valued Components Specific to the Edson Mainline Expansion Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alberta, 2021 Province of Canada

Quickworld Entity Report Alberta, 2021 Province of Canada Quickworld Factoid Name : Alberta Status : Province of Canada Active : 1 Sept. 1905 - Present Capital : Edmonton Country : Canada Official Languages : English Population : 3,645,257 - Permanent Population (Canada Official Census - 2011) Land Area : 646,500 sq km - 249,800 sq mi Density : 5.6/sq km - 14.6/sq mi Names Name : Alberta ISO 3166-2 : CA-AB FIPS Code : CA01 Administrative Subdivisions Census Divisions (19) Division No. 11 Division No. 12 Division No. 13 Division No. 14 Division No. 15 Division No. 16 Division No. 17 Division No. 18 Division No. 19 Division No. 1 Division No. 2 Division No. 3 Division No. 4 Division No. 5 Division No. 6 Division No. 7 Division No. 8 Division No. 9 Division No. 10 Towns (110) Athabasca Banff Barrhead Bashaw Bassano Beaumont Beaverlodge Bentley Black Diamond Blackfalds Bon Accord Bonnyville Bow Island Bowden Brooks Bruderheim Calmar Canmore Cardston Carstairs Castor Chestermere Claresholm Coaldale Coalhurst Cochrane Coronation Crossfield Crowsnest Pass Daysland Devon Didsbury Drayton Valley Drumheller Eckville Edson Elk Point Fairview Falher © 2019 Quickworld Inc. Page 1 of 3 Quickworld Inc assumes no responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions in the content of this document. The information contained in this document is provided on an "as is" basis with no guarantees of completeness, accuracy, usefulness or timeliness. Quickworld Entity Report Alberta, 2021 Province of Canada Fort MacLeod Fox Creek Gibbons Grande Cache Granum Grimshaw Hanna Hardisty High Level High Prairie High River Hinton Innisfail Killam Lac la Biche Lacombe Lamont Legal Magrath Manning Mayerthorpe McLennan Milk River Millet Morinville Mundare Nanton Okotoks Olds Oyen Peace River Penhold Picture Butte Pincher Creek Ponoka Provost Rainbow Lake Raymond Redcliff Redwater Rimbey Rocky Mountain House Sedgewick Sexsmith Slave Lake Smoky Lake Spirit River St. -

Targeted Residential Fire Risk Reduction a Summary of At-Risk Aboriginal Areas in Canada

Targeted Residential Fire Risk Reduction A Summary of At-Risk Aboriginal Areas in Canada Len Garis, Sarah Hughan, Paul Maxim, and Alex Tyakoff October 2016 Executive Summary Despite the steady reduction in rates of fire that have been witnessed in Canada in recent years, ongoing research has demonstrated that there continue to be striking inequalities in the way in which fire risk is distributed through society. It is well-established that residential dwelling fires are not distributed evenly through society, but that certain sectors in Canada experience disproportionate numbers of incidents. Oftentimes, it is the most vulnerable segments of society who face the greatest risk of fire and can least afford the personal and property damage it incurs. Fire risks are accentuated when property owners or occupiers fail to install and maintain fire and life safety devices such smoke alarms and carbon monoxide detectors in their homes. These life saving devices are proven to be highly effective, inexpensive to obtain and, in most cases, Canadian fire services will install them for free. A key component of driving down residential fire rates in Canadian cities, towns, hamlets and villages is the identification of communities where fire risk is greatest. Using the internationally recognized Home Safe methodology described in this study, the following Aboriginal and Non- Aboriginal communities in provinces and territories across Canada are determined to be at heightened risk of residential fire. These communities would benefit from a targeted smoke alarm give-away program and public education campaign to reduce the risk of residential fires and ensure the safety and well-being of all Canadian citizens. -

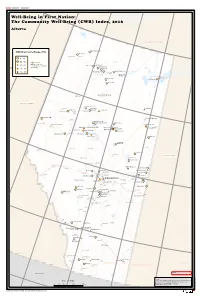

The Community Well-Being (CWB) Index, 2016

126° W 123° W 120° W 117° W 114° W 111° W Well-Being in First Nation: The Community Well-Being (CWB) Index, 2016 Alberta Bistcho Lake NORTHWEST TERRITORIES U¸ pper Hay River 212 CWB Index Score Range, 2016 H¸ ay Lake 209 ! Rainbow Lake Assumption ¸ ! N ° 0 0 - 49 6 ¸ Margaret 50 - 59 Higher scores Lake indicate a greater ·! 60 - 69 High Level !P B¸ ushe River 207 N level of socio-economic ° ¸ 7 Child Lake 164A 5 well-being. ¸ ^^ 70 - 79 Boyer 164 ¸ ¸ r John d'Or Prairie 215 Rive ! Peac e ^^ 80 - 100 Fort Vermilion 173B John D'Or !P !P Prairie ¸ La Crête !P Fox Lake Fox Lake 162 Fort Chipewyan ¸ Allison Bay 219 Tall Cree 173A ·! Dog Head 218 ·!!P Lake Athabasca ¸ Lake Tall Cree 173 Claire Richardson Lake r e v i R a c s a b a P h ! t Manning ALBERTA A BRITISH COLUMBIA Woo¸ dland Cree 226 ¸ Fort Mackay Fairview Woodland Grimshaw ¸ !P ¸ Cree 228 ^ !P P Loon Lake 235 ^ ! Little Buffalo Duncan's 151A Peace ·! River H¸ orse Lakes 152B Fort McMurray Falher " !P U¸ tikoomak Lake 155 P ¸ N ! ¸ Utikoomak Lake 155A Wabasca 166C ° 7 Beaverlodge 5 Gregoire Lake 176A Grande Prairie Utikuma North Wabasca " Lake Gordon " Lake ¸ ·! Lake Kapawe'no First Nation (Freeman 150B) Des¸ marais ·! Wabasca 166B ¸ Gregoire Lake 176 ! Wabasca 166A · ^ ¸ High Prairie !P Wabasca 166D ^ ·! Sucker Creek 150A Wabasca 166 ¸ ¸ Valleyview Sturgeon Lake 154 !P Lesser Slave Lake Drift Pile River 150 ! N · ° 4 ¸ 5 Swan River 150E Janvier 194 !P Slave Lake ¸ Jean Baptiste Gambler 183 Calling Lake Winefred Lake Fox Creek !PSwan Hills Grande Cache !P !P H¸ eart Lake 167 Athabasca Lac La !P Biche SASKATCHEWAN Whitecourt Lac La Biche !P !P B¸ eaver Lake 131 Barrhead Mayerthorpe !P !P Cold Hinton Lake !P ¸ !P White Fish Lake 128 ¸ Cold Lake 149B Edson Chip Lake ¸ Alexander 134 !P Alexis 133 Lac Grand Centre " Smoky Lake ¸ Ste. -

Alberta Census Subdivisions, Census Divisions and Economic Regions

Alberta Census Divisions and N O R T H W E S T T E R R II T O R II E S Census Subdivisions Kakisa River Buchan Charles Lake Lake 225 Beatty Lake Charles Lake Legend le o t l t r i fa L f e u iv Thebathi B R Economic Division No. 8 Census Bistcho 196 Pet itot Riv er Lake r e Regions (2011) Subdivision (2011) iv Division No. 9 R lo a ff u Alberta Census Division No. 10 Lakes B Divisions (2011) Division No. 11 Rivers Improvement District No. 24 r Census Division e Alberta Main iv Wood Buffalo R Division No. 12 y a Division No. 1 Roads H Slave Division No. 13 River !( Division No. 2 City Mackenzie Division No. 14 County !( Division No. 3 Town Upper Hay River 212 r Allison Lake Athabasca Division No. 15 e v !( i R Bay 219 Division No. 4 Village e c a Division No. 16 e Hay Lake Margaret P Division No. 5 Summer Village Lake Division No. 17 Zama k Lake Hay Division No. 6 Indian Reserve Lake Baril Division No. 18 209 Division No. 7 k Indian Settlement Lake Lake Claire Division No. 19 Child John d'Or Lake Prairie 215 Mamawi 164A Lake Hay River Rainbow Beaver Coordinate System: NAD 1983 10TM AEP Forest Lake Ranch 163 Fox High r Lake ve Projection: Transverse Mercator Ri h Level Bushe Boyer 162 rc Datum: North American 1983 Bi River 164 Fort Old 207 Vermilion Fort 217 173B 0 15 30 60 90 Kilometers ´ Tall Cree Chinc haga River 173A r Tall e v 16 i R Cree a r c e 173 s v Northern i River a a b R kw ik M a a Lights h c t s A County a 17 b Namur a W River 174A Wood Buffalo Legend Lake Namur Fort ATHABASCA-GRANDE Lake 174B Mackay PRAIRIE-PEACE RIVER Notikewin River Northern Sunrise Manning County WOOD BUFFALO- Clear Peace Clearwater River Hills River COLD LAKE Opportunity Loon No. -

DIAL 911 Sunbreaker Cove Road Rge Rd 2-2

-114°35'0" -114°32'30" -114°30'0" -114°27'30" -114°25'0" -114°22'30" -114°20'0" -114°17'30" -114°15'0" -114°12'30" -114°10'0" -114°7'30" -114°5'0" -114°2'30" -114°0'0" -113°57'30" -113°55'0" -113°52'30" -113°50'0" -113°47'30" -113°45'0" -113°42'30" -113°40'0" -113°37'30" -113°35'0" -113°32'30" -113°30'0" -113°27'30" -113°25'0" -113°22'30" -113°20'0" -113°17'30" -113°15'0" -113°12'30" -113°10'0" -113°7'30" -113°5'0" -113°2'30" -113°0'0" -112°57'30" -112°55'0" -112°52'30" -112°50'0" COUNTY STATISTICAL INFORMATION " R R R R 0 R " R R R R R R R R R R R 3 R R 0 R R R ' R g g g g g g g 3 d d g g g 1. AREA: 1,114 sq uare m ile s or 2,964 sq uare kilom e tre s. 7 d g ' d d d Rimbey d e d d d e d e 3 e e 7 e e e e e e ° R R R R 3 R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R 2 R R R 2 R R R R R R R R R R R R ° R R R R R R R R R R R R 2 R R R R R R R R R R R R R R 2 2 R R R R 2 R R R R R R 2 g g R R R R R R R R g g 2 g g R R R R g g g R R R R R R g g R g 2 R R R g g g 1 R g g g g g 4 5 d d R g g g d d g g g g d d g 2 d d d g g g d d g g 3 d g g g g g g 2. -

Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta : Community Profiles

For additional copies of the Community Profiles, please contact: Indigenous Relations First Nations and Metis Relations 10155 – 102 Street NW Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4G8 Phone: 780-644-4989 Fax: 780-415-9548 Website: www.indigenous.alberta.ca To call toll-free from anywhere in Alberta, dial 310-0000. To request that an organization be added or deleted or to update information, please fill out the Guide Update Form included in the publication and send it to Indigenous Relations. You may also complete and submit this form online. Go to www.indigenous.alberta.ca and look under Resources for the correct link. This publication is also available online as a PDF document at www.indigenous.alberta.ca. The Resources section of the website also provides links to the other Ministry publications. Introductory Note The Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta: Community Profiles provide a general overview of the eight Metis Settlements and 48 First Nations in Alberta. Included is information on population, land base, location and community contacts as well as Quick Facts on Metis Settlements and First Nations. The Community Profiles are compiled and published by the Ministry of Indigenous Relations to enhance awareness and strengthen relationships with Indigenous people and their communities. Readers who are interested in learning more about a specific community are encouraged to contact the community directly for more detailed information. Many communities have websites that provide relevant historical information and other background. Where available, these website addresses are included in the profiles. PLEASE NOTE The information contained in the Profiles is accurate at the time of publishing. -

First Nations and Indian Reserves Fire Losses, Alberta: 2000 - 2009 SOURCE: Office of the Fire Commissioner

First Nations and Indian Reserves Fire Losses, Alberta: 2000 - 2009 SOURCE: Office of the Fire Commissioner First Nations Reserve Fires Fire Deaths Fire Injuries $ Losses Siksika Nation 61 0 6 2,869,377 Blood Tribe 4 1 0 251,000 Cold Lake First Nations 7 0 1 279,633 Driftpile River Band 2 1 1 316,000 Enoch Cree Nation 16 1 0 1,355,988 Ermineskin Band 12 0 3 444,000 Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation 1 0 0 66,000 Fort McKay First Nation 1 0 0 135,000 Fort McMurray First Nation 1 0 0 59,980 Frog Lake First Nation 28 1 0 2,980,312 Jean Baptiste Gambler #183 1 1 0 30,000 Horse Lake Band 2 0 0 150,000 Chipewyan Prairie First Nation 2 0 0 135,000 Kehewin Cree Nation 6 0 0 714,824 Little Red River Cree Nation 2 0 0 76,000 Louis Bull Tribe 18 0 1 1,578,043 Montana Band 4 0 0 179,000 Onion Lake Band 1 0 0 71,245 Paul First Nation 6 0 0 2,350,000 Piikani Nation 5 0 0 189,570 Saddle Lake First Nation 6 0 0 216,651 Samson Cree Nation 43 0 1 3,583,203 First Nations Reserve Fires Fire Deaths Fire Injuries $ Losses Tsuu Tina Nation 27 0 1 691,373 Sturgeon Lake Band 6 0 0 237,821 Sucker Creek Band 2 0 0 327,000 Tallcree First Nation 1 0 0 40,000 Whitefish Lake First Nation 6 0 0 532,000 Alexander First Nation 7 0 1 31,705 Alexis First Nation #133 3 0 0 230,000 Beaver Lake Cree Nation 1 0 0 100,000 Bigstone Cree Nation 10 1 0 265,070 Saddle Lake #125 67 2 7 2,935,795 Whitefish Lake #128 33 0 0 1,941,042 Dene Tha First Nation 6 0 0 671,922 Loon River Cree Nation 1 0 0 40,760 Woodland Cree Band 3 2 0 145,000 Stoney (Chiniki) Band 1 0 0 40,000 Stoney (Wesley) -

Sec H Aboriginal Consultation and Assessment

Section H Aboriginal Groups Consultation and Assessment Benga Mining Limited Grassy Mountain Coal Project Section H: Aboriginal Groups Consulation and Assessment Table of Contents Page H. ABORIGINAL GROUPS CONSULTATION AND ASSESSMENT ........................................ H-1 H.1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... H-1 H.1.1 Aboriginal Consultation ........................................................................................................ H-2 H.2 ASSESSMENT METHODS ............................................................................................................ H-8 H.2.1 Project Setting and Background Information ..................................................................... H-9 H.2.2 Potential Effects on Aboriginal Valued Components ....................................................... H-9 H.2.3 Mitigation Measures ............................................................................................................ H-11 H.2.4 Characterization of Residual Effects .................................................................................. H-11 H.2.5 Cumulative Effects Assessment ......................................................................................... H-13 H.2.6 Follow-up and Monitoring Programs ............................................................................... H-13 H.2.7 Aboriginal Issues and Concerns ....................................................................................... -

South Part Alberta Partie Sud 16

South part Alberta Partie sud 16 120°W 119°W 118°W 117°W 116°W 115°W 114°W 113°W 112°W 111°W 110°W / Sturgeon Lake 154A, IRI 55°N Valleyview, T Heart Lake 167, IRI / 55°N Grande Prairie County No. 1, MD 18 818 / 18 018 12 840 19 006 Opportunity No. 17, MD 17 031 Sturgeon Lake 154, IRI 19 18 816 Lesser Slave River No.124, MD a c 17 033 s a b a h 17 t Big Lakes, MD A L 17 027 e a r Island Lake, SV c è la i 13 049 B v i Lac la Biche County, MD / che i Island Lake South, SV 12 037 R / / 13 051 r e West Athabasca County, MD v Whispering Hills, SV i Baptiste, SV 13 044 R 13 061 Swan Hills, T 13 057 / / 17 024 a c / s a b / a / / h / t Sunset Beach, SV Greenview No. 16, MD South Athabasca, T 18 015 A 13 047 Beaver Lake 131, IRI Baptiste, SV 13 048 Bondiss, SV Cold Lake 149B, IRI Boyle, VL 13 053 12 828 ld 13 055 / 13 046 12 815 Co / / ke / La Mewatha Beach, SV 13 045 Bonnyville No. 87, MD Cold Lake, CY / 12 004 12 002 18 Cold Lake / 149A, IRI Fox Creek, T 12 12 813 18 002 845 / / Larkspur, SV Cold Lake 13 033 Pelican Narrows, SV Bonnyville, T 149, IRI 12 013 12 009 / Glendon, VL 12 810 Woodlands County, MD Westlock County, MD / 12 012/ / 13 029 13 028 White Fish Lake 128, IRI 13 12 808 Smoky Lake County, MD / Thorhild County No. -

C-1 Aboriginal Groups

SAWRIDGE 150H SAWRIDGE 150G STURGEON LAKE 154A 116°0'0"W 115°0'0"W 114°0'0"W 113°0'0"W 112°0'0"W 111°0'0"W Sir Winston Churchill (PP) 858 N " 63 Lac la Biche Lakeland (PP) 0 ' 881 9 0 Lac La Biche Trea ° 9 ty 6 8, 1 8 8 5 9 5 7 9 5 Zone 1 8 MNAA , 1 Tr eat 8 , y 6 Lakeland (PRA) 813 , 18 6 76 one 4 y STURGEON LAKE 154B MNAA Z t 44 y 855 a t e a r e Athabasca River A l b e r t a T r r e T 663 iv R r Athabasca e N v " a e 0 BEAVER LAKE 131 ' B 0 3 ° G 812 4 801 5 oo Goose Mountain (ER) se Swan Hills R Cross Lake (PP) 663 iv er 55 801 36 B 881 ea ver BUFFALO LAKE Ri ver 663 MÉTIS SETTLEMENT 41 663 867 M KIKINO MÉTIS o Hubert Lake Wildland (WPP) os KP 280 827 SETTLEMENT ela 831 k 63 e R Spruce Island Lake (NA) iv 33 M e Long Lake (PP) 866 r Bonnyville N A 660 A White Earth Valley (NA) 855 r Moose Lake (PP) e Z v N i o " R n 0 e Moose Lake ' e WHITE FISH LAKE 128 661 k 0 a 4 l 3 n i ° r h 4 32 e 661 T 5 v Fort Assiniboine Sandhills Wildland (WPP) i 28A R a c s a Tawatinaw (NA) Fox Creek Sak b wa a tam h au R t KEHIWIN 123 iver A KP 270 ALEXANDER 134B 2 776 N Holmes Crossing Sandhills (ER) 769 Bellis North (NA) " KP 260 KP 240 0 KP 250 KP 230 Smoky Lake ' Carson-Pegasus (PP) 656 M 0 ALEXIS M 658 763 ° N N WHITECOURT 232 4 18 A BLUE QUILLS 5 Westlock A 859 28 ALEXANDER 134A A St. -

2004 Municipal Codes

LOCAL GOVERNMENT SERVICES DIVISION MUNICIPAL SERVICES BRANCH Updated January 2004 2004 MUNICIPAL CODES 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Internet: http://www.gov.ab.ca/ma/ms/ Phone: (780) 427-7495 Fax: (780) 422-9133 E-mail: [email protected] 2004 MUNICIPAL CHANGES STATUS CHANGES: NAME CHANGES: AMALGAMATED: FORMATIONS: DISSOLVED: 0223 - Village of Mirror (effective January 1, 2004) to Lacombe County. CODE NUMBERS RESERVED: 0522 - Metis Settlements General Council 0524 - R.M. of Brittania (Sask.) 0462 - Townsite of Redwood Meadows STATUS CODES: 01 - Cities (15)* 15 - Hamlet & Urban Services Areas 09 - Specialized Municipalities (4) 20 - Service Commissions 06 - Municipal Districts (64) 25 - First Nations 02 - Towns (110) 26 - Indian Reserves 03 - Villages (102) 50 - Local Government Associations 04 - Summer Villages (51) 60 - Disaster Services 07 - Improvement Districts (7) 70 - Regional Health Authorities 08 - Special Areas (3) 98 - Reserved Codes 11 - Metis Settlements 99 - Dissolved * (Includes Lloydminster) January 2004 Page 1 CITIES (Status Code 01) CODE CITIES (Status Code 01) CODE NO. NO. Airdrie 0003 Lethbridge 0203 Calgary 0046 Lloydminster* 0206 Camrose 0048 Medicine Hat 0217 Cold Lake 0525 Red Deer 0262 Edmonton 0098 Spruce Grove 0291 Fort Saskatchewan 0117 St. Albert 0292 Grande Prairie 0132 Wetaskiwin 0347 Leduc 0200 *Alberta only SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE (Status Code 09) NO. (Status Code 09) NO. Jasper, Municipality of 0418 Reg Mun of Wood Buffalo 0508 Mackenzie No. 23, M.D. of 0505 Strathcona County 0302 MUNICIPAL DISTRICTS CODE MUNICIPAL DISTRICTS CODE (Status Code 06) NO. (Status Code 06) NO. Acadia No. 34, M.D. -

Alberta Metis Settlement and First Nations Community Profiles

For additional copies of the Community Profiles, please contact: Indigenous Relations First Nations and Metis Relations 10155 – 102 Street NW Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4G8 Phone: 780-644-4989 Fax: 780-415-9548 Website: www.indigenous.alberta.ca To call toll-free from anywhere in Alberta, dial 310-0000. To request that an organization be added or deleted or to update information, please fill out the Guide Update Form included in the publication and send it to Indigenous Relations. You may also complete and submit this form online. Go to www.indigenous.alberta.ca and look under Resources for the correct link. This publication is also available online as a PDF document at www.indigenous.alberta.ca. The Resources section of the website also provides links to the other Ministry publications. ISBN 978-0-7785-9870-7 PRINT ISBN 978-0-7785-9871-8 WEB ISSN 1925-5195 PRINT ISSN 1925-5209 WEB Introductory Note The Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta: Community Profiles provide a general overview of the eight Metis Settlements and 48 First Nations in Alberta. Included is information on population, land base, location and community contacts as well as Quick Facts on Metis Settlements and First Nations. The Community Profiles are compiled and published by the Ministry of Indigenous Relations to enhance awareness and strengthen relationships with Indigenous people and their communities. Readers who are interested in learning more about a specific community are encouraged to contact the community directly for more detailed information. Many communities have websites that provide relevant historical information and other background.