Report on Spills in the Great Lakes Basin with a Special Focus on the St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Road Map of Ontario

4 Ipperwash 5 r Corbett e Corners 27 v Kettle Pt. Beach 21 i dc 18 19 20 hg 22 139 123 P R Harrin Northville a Grantonji24ji 28 83° 82° 10 rk 24 hi hg Ravenswood 18 ll C 24 hg 47 Uniondale 79 r. hg 59 hghg Clandeboye hgLucan 7 27 Medina Lakeside Thedford 21 hg hg 7 dc C.N.R. 25 Sylvan Parkhill hg R hg 9 6 6 20 Elginfield hg O 7 Ailsa Craig 119 hg hg 7 hg 7 M hg e ji N Lambton Shores Denfieldhg 23 16 E hg 4 d 31 12 9 17 w hg hg 27 16 Kintore 25 Forest dca hg Hi hg Bryanston cko hg Birr y hg hg hgr 6 28 R mn MICHIGAN U.S.A. y Nairn 20 hg 81 C hg ONTARIO CANADA hg Arkona A ble r Thorndale 7 30 hgusa Ilderton . X 21 Cr. 19 16 E hg 14 Brights hg hg Ballymote Fanshawe Point 11dc 12 hg 17 S 43°43° Grove Camlachie hgKeyser L. 2 hg . 28 Edward 13 9 79 hger 16 Cr Arva 27 Thamesford hg Port 7 Plympton-Wyoming iv E 20 hg hg Ing hghg R hg Huron 6 hg 30 Hickory hg 69 3 9 14 15 Warwick Coldstream O 9hg 9 34 22 Adelaide Corner LONDON 73 45 1 O O O 22 L rq O hg 22 Lobo Melrose hg hg O 22 25 10 hg 32 k . 11 Poplar 44 r 9 hg C.N.R. hgPu SarniahgMandauminOReece's 22 e 56 4 69 w hgDorchester43° e C 65 o Cors. -

Mysterious Windsor Hum Traced to Zug Island, Michigan. CBC

Mysterious Windsor Hum Traced to Zug Island, Michigan. CBC News, May 23, 2014 The source of the mysterious Windsor Hum in the southwestern Ontario city is on Zug Island — in River Rouge, Mich. — according to a federally funded report released today. Essex Conservative MP Jeff Watson released the report's findings at a news conference at the Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research at the University of Windsor on Friday. Watson said U.S. officials must now determine the precise location of the noise. Copies of the federal report have been given to Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder and the mayor of River Rouge. “We look forward to further discussions with them,” Watson said. The source of the mysterious Windsor Hum in the southwestern Ontario city is on Zug Island — in River Rouge, Mich. — according to a federally funded report released today. Essex Conservative MP Jeff Watson released the report's findings at a news conference at the Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research at the University of Windsor on Friday. Watson said U.S. officials must now determine the precise location of the noise. Copies of the federal report have been given to Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder and the mayor of River Rouge. “We look forward to further discussions with them,” Watson said. Zug Island is home to a U.S. Steel operation and is an area of concentrated steel production and other manufacturing. University of Windsor Prof. Colin Novak was one of the lead researchers. “Unfortunately, we weren’t able to find that smoking gun,” he said. Novak said he and his partners needed more time and U.S. -

Annual Report 2018-2019

Annual Report 2018‐2019 Science Education Partnership A better world through hands‐on, minds‐on science education 2018‐2019: KEY ACHIEVEMENTS classrooms were visited by volunteer farmers for Canada Agriculture Day science kits were revamped science kit bookings were made by different of schools within the teachers at schools Lambton Kent and St. Clair Catholic Districts accessed SEP programs this year, volunteers were active in the impacting an estimated newly students reorganized Science Discovery Squad volunteer 30 classrooms participated in the program unveiled National Engineering Month in February Challenge. A new Virtual Volunteer activity format was piloted with great success Page 1 NEW IN 2019: INTRODUCING THE SCIENCE DISCOVERY SQUAD The 2018‐2019 school year brought about exciting changes to SEP volunteer initiatives. The very first SEP volunteer program, “Adopt‐a‐ Scientist”, began in 1995 when Imperial Oil retirees were asked if they would like to help in the classroom. Initially, volunteers could be “adopted” by teachers who would have them in on a regular basis, but it soon became evident that educators were asking for help repeatedly in the same subject areas. In response, volunteers created interactive, hands‐on presentations that could travel to from Superintendents Laura Callaghan and Ben Hazzard, along with SEP Technician Wendy Hooghiem, watch pie plates fly from a classroom to classroom. Van der Graaf machine generator with SDS volunteer Peter Smith. In 2004, volunteer activities expanded to include bridge‐building sessions that celebrated National Engineering Month and fit with the Structures and Mechanisms strand of the Ontario Curriculum. Between 25 and 40 classes have participated each year since. -

Canadian Border Crossings

Canadian Border Crossings Port Canadian City/Town Province Highway Crossing U.S. City/Town Code 709 Chief Mountain Alberta Chief Mountain via Babb, MT 705 Coutts Alberta Hwy 4 Coutts Sweetgrass, MT 708 Del Bonita Alberta Del Bonita (via Cut Bank), MT 706 Aden Alberta Hwy 880 Whitlash, MT 711 Wild Horse Alberta Hwy 41 Simpson, MT 711 Wildhorse Alta. Hwy 41 Havre, MT 832 Paterson B. C. Northport, WA 841 Aldergrove British Columbia BC 13 Lynden, WA Boundary Bay British Columbia Boundary Bay Point Roberts, WA 840 Douglas British Columbia Peace Arch Blaine, WA 829 Flathead British Columbia Trail Creek, 817 Huntingdon British Columbia BC11 Huntingdon Sumas, WA 813 Pacific Highway British Columbia BC 15 Pacific Highway Blaine, WA 824 Roosville British Columbia Roosville Eureka, MT 822 Rykerts British Columbia Porthill, ID 816 Cascade British Columbia Hwy 3 Laurier, WA Grand Forks British Columbia Hwy 3 Danville, WA 818 Kingsgate British Columbia Hwy 3 Eastport, ID 835 Midway British Columbia Hwy 3 Ferry, WA 828 Nelway British Columbia Hwy 6 Metaline Falls, WA 819 Osoyoos British Columbia Hwy 97 Oroville, WA 507 Boissevain Manitoba Dunseith, ND Middleboro Manitoba Warroad, MN 506 South Junction Manitoba Roseau, MN 521 Cartwright Manitoba Hwy 5 Hansboro, ND 524 Coulter Manitoba Hwy 83 Westhope, ND 520 Crystal City Manitoba Hwy 34 Sarles, ND Hwy 75 / Manitoba 502 Emerson Highway 29 Emerson Pembina, ND Gainsborough Manitoba Hwy 256 Antler, ND Goodlands Manitoba Hwy 21 Carbury, ND 503 Gretna Manitoba Hwy 30 Neche, ND Haskett Manitoba Hwy 32 Walhalla, ND 522 Lena Manitoba Hwy 18 St. -

ST. CLAIR TUNNEL HAER No. MI-67 (St

ST. CLAIR TUNNEL HAER No. MI-67 (St. Clair River Tunnel) Under the St. Clair River, between Port Huron, HA^l: f> . Michigan, and Sarnia, Canada ih \ .~~; (~ ; Port Huron ' '*■ • ''-•■- H ■ St. Clair County *7U^--fQH\jt Michigan ''/[ • PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service Northeast Region U.S. Custom House 200 Chestnut Street Philadelphia, PA 19106 # HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD ST. CLAIR TUNNEL (St. Clair River Tunnel) HAER No. MI-67 Location: Under the St. Clair River, between Port Huron, Michigan, and Sarnia, Canada TJTM: A: 17.382520.4757260 C: 17.385690.4756920 B: 17.382470.47 57150 D: 17.385650.4756S20 Quad: Port Huron, MI, 1; 2 4,0 0 0 Dates of Construction: 1888-1891; 1907-1908; 1958 Engineer: Joseph Hobson and others Present Owner: St Clair Tunnel Company, 1333 Brewery Park Boulevard, Detroit, Michigan 48207-9998 Present Use; Railroad tunnel Significance: The St. Clair Tunnel was the first full- sized subaqueous tunnel built in North America. Joseph Hobson, the Chief Engineer, successfully combined three significant new technologies—a tunnel shield driven by hydraulic rams; a cast iron tunnel lining; and the use of a compressed air environment. This tunnel eliminated a major bottleneck in the rail transportation system linking the American midwest with its eastern markets. Project Information; This documentation is the result of a Memorandum of Agreement, among the Michigan State Historic Preservation Office, the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, the Department of the Army, Corps of Engineers, Detroit District and the Canadian National North America Railroad as a mitigative measure before the closing of the tunnel. -

Mayor and Members of Council From

Municipality Of Chatham-Kent Infrastructure and Engineering Services Public Works To: Mayor and Members of Council From: Ryan Brown, P.Eng. Director of Public Works Gabriel Clarke, MES, BA Environmental Planner I Date: April 28, 2021 Subject: Amendments to Long Grass and Weeds By-Law 56-2020 Recommendations It is recommended that: 1. The attached by-law to regulate and prohibit long grasses and weeds be approved. 2. By-Law Number 56-2020, the former bylaw to regulate and prohibit long grasses and weeds be repealed. Background At the September 14, 2020 meeting, Council approved the following Motion: “Chatham-Kent’s Long Grass and Weed By-law (By-law # 56-2020) was introduced to implement a minimum outdoor landscaping maintenance standard that prohibits overgrown grasses and weeds on private properties. Similar to long grass by-laws in other communities, Chatham-Kent’s By-law maintains community aesthetics and prevents landscape abandonment. The by-law applies to all grass and weed species listed in the Government of Ontario’s Publication 505 ‘Ontario Weeds’ and requires that they be kept under 20cm in height through regular mowing, or be subject to enforcement. However, it is also a community strategic objective to enhance natural areas in the Municipality and there is a conflict that exists with the long grass by-law in meeting these objectives. Specifically, there are challenges that the current grass cutting by- law poses with respect to legitimate tall grass prairie environmental naturalization activities on private lands and despite the positive intent of the by-law, the way it is currently written can be used to reverse these environmental stewardship activities that the Municipality has otherwise identified as desirable. -

GREAT LAKES MARITIME INSTITUTE DOSSIN GREAT LAKES MUSEUM Belle Isle, Detroit, Michigan 48207 I U1

MARCH ☆ APRIL, 1983 Volume XXXII; Number 2 GREAT LAKES MARITIME INSTITUTE DOSSIN GREAT LAKES MUSEUM Belle Isle, Detroit, Michigan 48207 I u1. TELESCOPE Page 30 MEMBERSHIP NOTES • In the January issue of Telescope, we stated that the whaleback Meteor had been scrapped in 1969. The photo caption should have read retired in 1969. We regret the error and hope that our members will visit the museum ship when they visit Superior, Wisconsin. The 1983 Ship Model Contest will be held in October. The entry deadline is September 15, 1983. Those interested should send a self-addressed envelope to the museum for details. Dr. Charles and Jeri Feltner have written a book on reference sources for Great Lakes History. Great Lakes Maritime History: Bibliography and Sources of Information contains over one thou sand entries divided into catagories such as reference works, directories and registries, ship building and construction, U.S. Government organizations and societies and archives. Those interested should write Seajay Publications, P.O. Box 2176, Dearborn, Michigan 48123 for further information. Within the next few months, the Institute will print a list of items available by mail from our gift shop. Those interested in receiving a copy should send a self-addressed envelope to the Museum. MEETING NOTICES • Jacqueline Rabe will be our guest speaker at the next entertainment meeting on March 18. (See meeting notice on page 55.) All members are invited to bring 10-15 of their best slides taken at the Soo Locks and St. Marys River to the May entertainment meeting scheduled for May 20. Future business meetings are scheduled for April 15 and June 17. -

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan A Comprehensive Listing of the Vessels Built from Schooners to Steamers from 1810 to the Present Written and Compiled by: Matthew J. Weisman and Paula Shorf National Museum of the Great Lakes 1701 Front Street, Toledo, Ohio 43605 Welcome, The Great Lakes are not only the most important natural resource in the world, they represent thousands of years of history. The lakes have dramatically impacted the social, economic and political history of the North American continent. The National Museum of the Great Lakes tells the incredible story of our Great Lakes through over 300 genuine artifacts, a number of powerful audiovisual displays and 40 hands-on interactive exhibits including the Col. James M. Schoonmaker Museum Ship. The tales told here span hundreds of years, from the fur traders in the 1600s to the Underground Railroad operators in the 1800s, the rum runners in the 1900s, to the sailors on the thousand-footers sailing today. The theme of the Great Lakes as a Powerful Force runs through all of these stories and will create a lifelong interest in all who visit from 5 – 95 years old. Toledo and the surrounding area are full of early American History and great places to visit. The Battle of Fallen Timbers, the War of 1812, Fort Meigs and the early shipbuilding cities of Perrysburg and Maumee promise to please those who have an interest in local history. A visit to the world-class Toledo Art Museum, the fine dining along the river, with brew pubs and the world famous Tony Packo’s restaurant, will make for a great visit. -

Zug Island: More Than Next Wind Power Mayor at Stake Mecca? Donors Move from Filling $56M Backs Bid for Gaps to Guiding Development

20091026-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 10/23/2009 6:55 PM Page 1 ® www.crainsdetroit.com Vol. 25, No. 42 OCTOBER 26 – NOVEMBER 1, 2009 $2 a copy; $59 a year ©Entire contents copyright 2009 by Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved Philanthropy Detroit Election Zug Island: More than next Wind power mayor at stake mecca? Donors move from filling $56M backs bid for gaps to guiding development. Focus, Pages 13-20 Vote seen as referendum on city’s future drivetrain facility BY NANCY KAFFER drop of a rapidly approaching Nov. 3 elec- Y OM ENDERSON CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS tion that will seat a four-year, full-term may- B T H Foundation portfolio values or. AND RYAN BEENE back on the rise, Page 3 etroit Mayor Dave Bing took office in Challenger Tom Barrow, who took about CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS May, campaigning on his acumen as a 10,000 ballots in the August primary to D political outsider and business leader, Keith Cooley, the CEO of NextEnergy, has put Bing’s roughly 68,000, has opposed the may- together a consortium of industry heavy- Inside a guy who could make the tough choices or on almost every point: criticizing Bing’s needed to right the listing ship of Detroit fi- weights and lined up about $56 million in cuts, his treatment of the unions and his matching-fund commitments Dan Gilbert spends $15.4M nances. interactions with regional Five months later, Bing has as it awaits word on a $45 mil- on chance at Ohio casino, leaders. -

Docket 85 Port Huron-Sarnia Detroit

I. ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF STATE WASH I N GTO N The International Joint Commission, United States and Canada, Washington, D .C. , U.S .A., and Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. I .. .d Sirs: As a result of expand.ing industrial and other activities along the international boundary of the United States and Canada, the Governments of both countries have been increasingly aware of the problem of air pollution affecting citizens and property interests on either side of the boundary. In particular, Governments have received representations that citizens and property in the vicinities of Detroit-Windsor and Port Huron-Sarnia are being subjected to detrimental quantities of air pollutants crossing the boundary. The problem of air pollution in the vicinity of the cities of Windsor and Detroit was the subject of a Joint Reference to the Commission dated January 12, 1949. The Commission was requested to report whether the air over, or in the vicinity of, Detroit and Windsor was being polluted by smoke, soot, fly ash or other impurities in quantities detrimental to the ..i public health, safety or general welfare of citizens 1 or property on either side of the boundary. In the event of an affirmative answer, the Commission was ..., i asked to indicate the extent to which vessels plying '1 I the waters of the Detroit River were contributing to this pollution and what other major factors were responsible and to what extent. m-F?. The Commission, in its final report to Governments RCi;ilpn,. 0-f May 1960.,,.repliedin the affirmative to the first question and listed various industrial, domestic and 1 'I 4. -

Egg Deposition by Lithophilic-Spawning Fishes in the Detroit and Saint Clair Rivers, 2005–14

Egg Deposition by Lithophilic-Spawning Fishes in the Detroit and Saint Clair Rivers, 2005–14 Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5003 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Viable lake whitefish eggs collected from the Detroit River. Photograph by U.S. Geological Survey Great Lakes Science Center staff. Egg Deposition by Lithophilic-Spawning Fishes in the Detroit and Saint Clair Rivers, 2005–14 By Carson G. Prichard, Jaquelyn M. Craig, Edward F. Roseman, Jason L. Fischer, Bruce A. Manny, and Gregory W. Kennedy Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5003 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2017 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Prichard, C.G., Craig, J.M., Roseman, E.F., Fischer, J.L., Manny, B.A., and Kennedy, G.W., 2017, Egg deposition by lithophilic-spawning fishes in the Detroit and Saint Clair Rivers, 2005–14: U.S. -

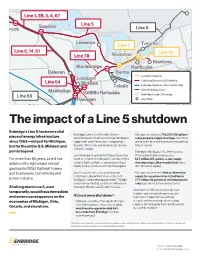

The Impact of a Line 5 Shutdown

Line 1, 2B, 3, 4, 65, 67 Gretnana Montreal Line 1, 2B, 3, 4, 67 Superior Line 5 Clearbrook Line 9 Lewiston Line 7 Toronto Line 6, 14, 61 Line 10 Line 78 Westover Kiantone Stockbridge Nanticoke Delevan Sarnia CanadianLine Mainline 11 Lockport Lakehead System (U.S. Mainline) Line 64 Mokena Toledo EnbridgeLine Pipelines 79 (Joint Ownership) Other Enbridge Lines Manhattan Grith/Hartsdale Line 55 Enbridge Crude Oil Storage Flanagan City/TownLine 17 Salisbury Patoka Line 62 The impactWood River of a Line 5 shutdown Enbridge’s Line 5 has been a vital Enbridge’s Line 5 is a 645-mile, 30-inch- • Michigan would face a 756,000-US-gallons- piece of energy infrastructure diameter pipeline that travels through Michigan’s a-day propane supply shortage, since there since 1953—not just for Michigan, Upper and Lower Peninsulas—originating in are no short-term alternatives for transporting but for the entire U.S. Midwest and Superior, Wisconsin, and terminating in Sarnia, NGL to market. Ontario, Canada. points beyond. • The region (Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Line 5 transports up to 540,000 barrels per day Ontario and Quebec) would see a For more than 65 years, Line 5 has (bpd), or 22.68 million US gallons per day, of light 14.7-million-US-gallons-a-day supply delivered the light oil and natural crude oil, light synthetic crude and natural gas shortage of gas, diesel and jet fuel (about liquids (NGLs), which are refined into propane. 45% of current supply). gas liquids (NGL) that heat homes and businesses, fuel vehicles and Line 5 supplies 65% of propane demand • Michigan would need to find an alternative in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, and 55% of supply for anywhere from 4.2 million to power industry.