The Decline of Crisis and Community Care Support in England: Why a New Approach Is Needed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Social Fund Commissioner's Annual Report

The Social Fund Commissioner’s Annual Report 2011/2012 1112 The Social Fund Commissioner’s Annual Report 2011/2012 1112 The Social Fund Commissioner’s Annual Report 2011/2012 Rt. Hon. Iain Duncan Smith MP Secretary of State for Work and Pensions Caxton House, Tothill Street London SW1H 9DA Dear Secretary of State I am pleased to present my third Annual Report to you since my appointment as the Social Fund Commissioner for Great Britain. I report on the achievements of my staff in the Independent Review Service during the year ending March 2012. The calls on our service to provide an independent review have remained high. We have continued to resolve cases quickly and effectively within challenging timescales; maintained high quality standards in our decisions through innovation and adapting our approach; and retained high levels of satisfaction on the part of customers and those acting for them. I was pleased to note that both Chairmen of the Administrative Justice and Tribunals Council and the Ombudsman Association have commented in very positive terms about the quality and accessibility of our service. Our primary responsibility is to ensure that we deliver a high quality service to a poor and vulnerable section of the community. We are conscious that we are also accountable to the taxpayer in terms of securing value for money. I am pleased to report that our unit cost per case during this past year was £74, a reduction from £86 during the previous year, which we achieved without any decline in the quality of our decision making or service to the public. -

Devolved Social Security Powers: Progress and Plans

SPICe Briefing Pàipear-ullachaidh SPICe Devolved social security powers: progress and plans Camilla Kidner This briefing provides an update on the devolution of certain aspects of social security, primarily following the Scotland Act 2016. By 2024 Social Security Scotland is expected to be delivering a range of social security provision including carer's and disability benefits. A separate briefing will provide further detail on individual benefits. This paper focuses on the timeline, delivery agencies and funding. 10 May 2019 SB 19-27 Devolved social security powers: progress and plans, SB 19-27 Contents Executive Summary _____________________________________________________3 Introduction ____________________________________________________________4 Social security timeline: 'safe and secure transfer' ____________________________6 Devolved social security: 2013 to 2019 ______________________________________7 Devolved social security: 2020 to 2024 ______________________________________7 Legislative process from devolution to delivery _______________________________8 Organisational structure of devolved social security ____________________________9 Social security programme_____________________________________________10 Funding devolved social security _________________________________________12 Baseline _____________________________________________________________12 Ongoing funding for disability and carer benefits and winter payments_____________12 Ongoing funding for other benefits_________________________________________13 Setting the -

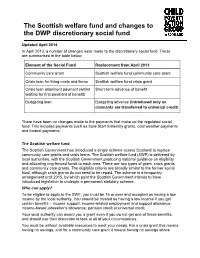

The Scottish Welfare Fund and Changes to the DWP Discretionary Social Fund

The Scottish welfare fund and changes to the DWP discretionary social fund Updated April 2014 In April 2013, a number of changes were made to the discretionary social fund. These are summarised in the table below. Element of the Social Fund Replacement from April 2013 Community care grant Scottish welfare fund community care grant Crisis loan for living costs and items Scottish welfare fund crisis grant Crisis loan alignment payment (whilst Short-term advance of benefit waiting for first payment of benefit) Budgeting loan Budgeting advance (introduced only as claimants are transferred to universal credit) There have been no changes made to the payments that make up the regulated social fund. This includes payments such as Sure Start maternity grants, cold weather payments and funeral payments. The Scottish welfare fund The Scottish Government has introduced a single scheme across Scotland to replace community care grants and crisis loans. The Scottish welfare fund (SWF) is delivered by local authorities, with the Scottish Government producing national guidance on eligibility and allocating ring-fenced funds to each area. There are two types of grant, crisis grants and community care grants. The eligibility criteria are broadly similar to the former social fund, although crisis grants do not need to be repaid. The scheme is a temporary arrangement until 2015, by which point the Scottish Government intends to have introduced legislation to underpin a permanent statutory scheme. Who can apply? To be eligible to apply to the SWF, you must be 16 or over and accepted as having a low income by the local authority. -

Form SF500 Budgeting Loans from the Social Fund

Notes sheet Budgeting Loans from the Social Fund Please read these notes carefully. They explain the We cannot help with any other types of items or services. circumstances when a loan can be paid. Different circumstances Budgeting Loans have to be paid back but they are interest free. apply to payments of Community Care Grants and Crisis Loans. You can have one of three rates of Budgeting Loan. The amount depends on whether you If you think you may be eligible for either of these types of are single, a couple without children or qualifying young persons or a one or two parent payments, read the section on the other side of this page. family with children or qualifying young persons. You will need to fill in the right application form for the type of The amount of Budgeting Loan you can have also depends on whether you have any other payment you need. These are: budgeting loans from the Social Fund. The amount of any Budgeting Loan we may pay ● form SF300 for a Community Care Grant together with the amount you still owe the Social Fund cannot be more than £1,500. ● form SF500 for a Budgeting Loan ● form SF401 for a Crisis Loan Savings ● form SF100 (Sure Start) for a Sure Start Maternity Grant ● If you and your partner are aged under 60, savings of more than £1,000 may affect the ● form SF200 for a Funeral Payment amount of money you can get. You must fill in a separate form for each one. ● If you or your partner are aged 60 or over, savings of more than £2,000 may affect the amount of money you can get. -

Community Care Grants – Example Cases

Orkney Islands Council Scottish Welfare Fund. Community Care Grants – example cases This guide provides some examples of possible Community Care Grant applications and whether the applicant may be eligible to receive a grant award or not. It does not cover all types of scenarios but should give you an example of the types of grants that people apply for and the type of decision that may be made. Please note that even if your circumstances may be the same as one of the examples it does not mean that the decision will be the same, as you may have slightly different needs or be considered as a different priority. It is aimed as a guide only. A Community Care Grant may be awarded To help people establish themselves in the community following a period of care where circumstances indicate that there is an identifiable risk of the person not being able to live independently without this help. • The person must have been in accommodation for 3 months or more where they received significant and substantial care, supervision or protection. For example hospital, care homes, hostels, prison or supported accommodation. • Example cases can be found at Annex 1 to this document. • To help people remain in the community rather than going into care where circumstances indicate that there is an identifiable risk of the person not being able to live independently without this help. • People most at risk of going into care may be those having difficulty dealing with life in the community, for example: dealing with personal and domestic tasks, needing basic household items, repairs to maintain or improve a home or help someone to move to provide care for someone. -

The Social Fund and Local Government

234 the Social Fund and local government January 2006 research LGA Foreword The Social Fund is probably the most researched contemporary area of social security policy, particularly in relation to the size of its budget. We make no apology for returning to it yet again for just as it is heavily researched, so it is heavily criticised. A series of administrative changes to it over the years since it was introduced in 1988 have not dispelled the major criticisms of it – its small budget, mysterious decision-making procedures, high refusal rates, and dependence on loans – criticisms which have come from all quarters, including politicians, benefit advisers, academics, the National Audit Office, the Auditor General, the Social Security Advisory Committee, the Social Fund Commissioner, the House of Commons Select Committee, local government, the voluntary sector, trades unions representing those administering the Fund, and, not least from benefit claimants themselves. Despite early political commitments to reform it thoroughly or even abolish it and replace it with a more acceptable way of providing cash help to claimants on the lowest incomes, the New Labour government has persisted with the Fund and these criticisms remain. This report was commissioned to explore one less well-researched area, the impact of the Social Fund on local government. The sometimes apocalyptic fears expressed by local government social workers and benefit advisers in the run-up to 1988 have not, in the event, been realised. Nevertheless, despite the difficulties of collecting systematic data, and the fact that applicants to the Social Fund whose applications are rejected rarely mention local government as an obvious source of financial help (Finch and Kemp 2004) it is clear that the Fund has negative effects on local government, most of all in the human and financial resources which are expended in supporting claimants whose legitimate claims for help have been rejected by the Social Fund, largely because of its capped budget and poor decision-making. -

The Scottish Welfare Fund and Changes to the DWP Social Fund

The Scottish welfare fund and changes to the DWP social fund This is one of a series of Child Poverty Action Group in Scotland factsheets giving guidance to advisers and those working with families in Scotland. Child Poverty Action Group promotes action for the prevention and relief of poverty among children and families with children. The Scottish welfare fund and changes to the DWP social fund Introduction In April 2013, a number of changes were made to the DWP discretionary social fund. These are summarised in the table below. Element of the Social Fund Replacement Community care grant Scottish welfare fund community care grant Crisis loan for living costs and items Scottish welfare fund crisis grant Crisis loan alignment payment (whilst waiting for Short-term advance of benefit first payment of benefit) Budgeting loan Budgeting advance (introduced only as claimants move to universal credit) This factsheet explains these changes. Future Changes There have been no changes made to the payments that make up the regulated social fund. This includes: • Sure Start maternity grants • funeral payments • cold weather payments • winter fuel payments However, it is planned that responsibility for the regulated social fund will be devolved to the Scottish Government, which will be able to change amounts or entitlement conditions. At the time of writing it is not clear exactly when this will happen. The following payments will remain the responsibility of the DWP: • budgeting loans • budgeting advances • short term benefit advances These payments are explained later in this factsheet. The Scottish welfare fund The Scottish welfare fund (SWF) is delivered by local authorities, with the Scottish Government allocating ring-fenced funds to each authority. -

Social Security Advisory Committee

503568_SS_Adv_22_cov_AW 30/10/09 11:42 Page 1 SOCIAL SECURITY ADVISORY COMMITTEE Twenty-second Report 2009 Social Security Advisory Committee internet: www.ssac.org.uk E-mail: [email protected] Crown Copyright 2009. Published for the Department for Work and Pensions on behalf of the Social Security Advisory Committee under licence from the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Application for reproduction should be made in writing to The Copyright Unit, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, St Clements House, 2–16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ. First Published 2009 Social Security Advisory Committee TWENTY SECOND REPORT AUGUST 2008 – JulY 2009 Members Sir Richard Tilt (Chairman) Kwame Akuffo Les Allamby John Andrews (from April 2009) Simon Bartley Brigid Campbell Dr Angus Erskine Richard Exell (to June 2009) Alison Garnham Carolyn George (from April 2009) Professor Elaine Kempson Laurie Naumann (to November 2008) Professor Anthony Ogus (to October 2008) Maureen Reith (from January 2009) Pat Smail Professor Janet Walker Professor Robert Walker Secretariat Gill Saunders (Secretary) Dr Anna Bee (from October 2008) Dr Nicola Moss (from September 2008) Ethna Harnett Heather Gray (January 2009 to June 2009) Daniel Cross (from June 2009) Jamie Allen Natalie Harwood Address Social Security Advisory Committee North East Spur Level 3 The Adelphi 1-11 John Adam Street London WC2N 6HT Internet website: http://www.ssac.org.uk E-mail: [email protected] i © Crown copyright 2009 Applications for reproduction should be made to HMSO First published -

Winter Fuel Payments Update

BRIEFING PAPER CBP-6019, 5 November 2019 Winter Fuel Payments By Djuna Thurley, Rod McInnes, Steven Kennedy update Inside: 1. Introduction 2. Purpose of the Winter Fuel Payment 3. Eligibility 4. Winter Fuel Payment rates 5. Payment abroad 6. Early Winter Fuel payments for “off-gas grid” households 7. Criticisms of the Winter Fuel Payment 8. Options for reform www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 6019, 5 November 2019 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Introduction 4 1.1 Overview 4 1.2 Statistics 5 1.3 Devolution 6 2. Purpose of the Winter Fuel Payment 7 3. Eligibility 8 4. Winter Fuel Payment rates 9 5. Payment abroad 12 5.1 Introduction of the ‘temperature link’ 13 6. Early Winter Fuel payments for “off-gas grid” households 16 7. Criticisms of the Winter Fuel Payment 18 8. Options for reform 26 8.1 Means-testing 26 8.2 Make the Winter Fuel Payment taxable 27 8.3 Withdraw from higher income pensioners 27 Cover page image copyright: Gas Flame by Thomas. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 / image cropped. 3 Winter Fuel Payments update Summary The Winter Fuel Payment is a tax-free annual payment to help older people pay their winter heating bills. Most payments are made automatically between November and December. Individuals usually get a Winter Fuel Payment automatically if they get the State Pension or certain other benefits. The “standard” rates are £200 per eligible household where the oldest person is under 80, and £300 for households containing a person aged 80 or over. -

Introduction to Benefits and Tax Credits

Introduction to Benefits and Tax Credits August 2020 Contents A) Introduction __________________________________________________ 1 B) The benefit structure and welfare reform __________________________ 2 C) The benefits __________________________________________________ 4 1) Non Means-Tested Benefits ................................................................................ 4 2) Means Tested Benefits ...................................................................................... 11 3) Other help: one-off and weekly payments, help with work ............................ 15 4) Table of benefits ................................................................................................. 18 D) Some general principles ______________________________________ 19 1) General benefit rules .......................................................................................... 19 2) Administration – who deals with what benefit? .............................................. 22 3) Contacting benefit offices ................................................................................. 23 4) Claims and payments ........................................................................................ 23 5) Decisions and delays ......................................................................................... 26 6) Challenging decisions and changing awards ................................................. 26 7) Complaints ......................................................................................................... -

Essential Living Fund (ELF)

Bromsgrove District Council Essential Living Fund (ELF) Table of Contents Bromsgrove District Council Essential Living Fund (ELF) .......................................... 1 Essential Living Fund - Mission Statement ............................................................. 2 1. Purpose of the Scheme ...................................................................................... 3 2. Start Date of the Scheme.................................................................................... 3 3. Decision Makers ................................................................................................. 3 4. Purpose of the Fund ........................................................................................... 4 5. How Much to Award............................................................................................ 6 6. Eligibility.............................................................................................................. 7 7. Number of Awards and Repeat Applications .................................................... 10 8. Applications ...................................................................................................... 12 9. Evidence........................................................................................................... 12 10. Reviewing A Decision ..................................................................................... 14 APPENDIX A ....................................................................................................... -

Unfair and Underfunded

Unfair and underfunded CAB evidence on what’s wrong with the Social Fund This report was written by Alan Barton, National Association of Citizens Advice Bureaux October 2002 Contents 1. Summary and recommendations 1 2. Introduction 5 The need for change 5 What is the Social Fund for? 6 What does the Social Fund provide? 7 3. General problems with the Social Fund 9 Grants or loans? 9 Inadequate advice from social security staff 10 Is the budget adequate to meet need? 12 Is the Social Fund efficient and effective 14 Eligibility – the people who miss out 14 Alternative help- The Association of Charity Officers 17 4. Specific problems with the Social Fund 20 Community Care Grants 20 Budgeting Loans 23 Crisis Loans 27 Funeral Payments 33 5. Conclusion 39 Appendix: CABx that submitted evidence between January 1999 and July 2002 40 Unfair and underfunded Summary and recommendations 1. Summary and recommendations 1.1 The Social Fund exists to enable people on very low incomes to meet needs that they cannot afford from their normal benefit income. These needs include such things as the cost of clothes and other equipment for a new baby, beds and cookers for people setting up home after homelessness or mental illness, or the costs of replacing essential items destroyed in a fire. In this Evidence Report we draw attention to the manifest failings of the Social Fund to meet the needs of people on low incomes. These failings have left some of the poorest and most vulnerable people in society socially excluded and deprived of the necessities for a decent standard of life.