Chris Borland, Fearing for Health, Retires from the 49Ers. at 24

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Game Summaries:IMG.Qxd

Sunday, September 12, 2010 Green Bay Packers 27 Lincoln Financial Field Philadelphia Eagles 20 Clad in their Kelly green uniforms in honor of the 1960 NFL cham- 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Pts pions, the Philadelphia Eagles made a valiant comeback attempt Green Bay 013140-27 but fell just short in the final minutes of the season opener vs. Green Philadelphia 30710-20 Bay. Philadelphia fell behind 13-3 at half and 27-10 in the 4th quar- ter and lost four key players along the way: starting QB Kevin Kolb Phila - D.Akers, 45 FG (8-26, 4:00) (concussion), MLB Stewart Bradley (concussion), FB Leonard GB - M.Crosby, 49 FG (10-43, 5:31) Weaver (ACL), and C Jamaal Jackson (triceps). But behind the arm GB - D. Driver, 6 pass from Rodgers (Crosby) (11-76, 5:33) and legs of back-up signal caller Michael Vick, the Eagles rallied to GB - M.Crosby, 56 FG (7-39, 0:41) make the score 27-20 late in the 4th quarter. In fact, they took over GB - J.Kuhn, 3 run (Crosby) (10-62, 4:53) possession at their own 24-yard-line with 4:13 to play and drove to Phila - L.McCoy, 12 run (Akers) (9-60, 4:12) the GB42 before Vick was tackled short of a first down on a 4th-and- GB - G.Jennings, 32 pass from Rodgers (Crosby) (4-51, 2:28) 1 rushing attempt to seal the Packers victory. After the Eagles took Phila - J.Maclin, 17 pass from Vick (Akers) (9-79, 3:39) a 3-0 lead after an interception by Joselio Hanson, Green Bay took Phila - D.Akers, 24 FG (9-45, 3:31) control over the remainder of the first half. -

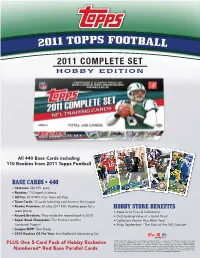

2011 Topps Football 2011 Complete Set Hobby Edition

2011 TOPPS FOOTBALL 2011 COMPLETE SET HOBBY EDITION All 440 Base Cards including 110 Rookies from 2011 Topps Football BASE CARDS • 440 • Veterans: 262 NFL pros. • Rookies: 110 hopeful talents. • All-Pro: 2010 NFL First Team All-Pros. • Team Cards: 32 cards featuring each team in the league. • Rookie Premiere: 30 elite 2011 NFL Rookies pose for a HOBBY STORE BENEFITS team photo. • Appeals to Fans & Collectors! • Record Breakers: They made the record book in 2010. • Outstanding Value at a Great Price! • Super Bowl Champions: The Packers and the • Collectors Return Year After Year! Lombardi Trophy! • Ships September - The Start of the NFL Season! • League MVP: Tom Brady • 2010 Rookies Of The Year: Sam Bradford & Ndamukong Suh ® TM & © 2011 The Topps Company, Inc. Topps and Topps Football are trademarks of The Topps Company, Inc. All rights reserved. © 2011 NFL Properties, LLC. Team Names/Logos/Indicia are trademarks of the teams indicated. All other PLUS One 5-Card Pack of Hobby Exclusive NFL-related trademarks are trademarks of the National Football League. Officially Licensed Product of NFL PLAYERS | NFLPLAYERS.COM. Please note that you must obtain the approval of the National Football League Properties in promotional materials that incorporate any marks, designs, logos, etc. of the National Football League or any of its teams, unless the Numbered* Red Base Parallel Cards material is merely an exact depiction of the authorized product you purchase from us. Topps does not, in any manner, make any representations as to whether its cards will attain any future value. NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. PLUS ONE 5-CARD PACK OF HOBBY EXCLUSIVE NUMBERED RED BASE PARALLEL CARDS 2011 COMPLETE SET CHECKLIST 1 Aaron Rodgers 69 Tyron Smith 137 Team Card 205 John Kuhn 273 LeGarrette Blount 341 Braylon Edwards 409 D.J. -

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release Game 12: Miami Dolphins (4-7) vs. Baltimore Ravens (4-7) Sunday, Dec. 6 • 1 p.m. ET • Sun Life Stadium • Miami Gardens, Fla. RESHAD JONES Tackle total leads all NFL defensive backs and is fourth among all NFL 20 / S 98 defensive players 2 Tied for first in NFL with two interceptions returned for touchdowns Consecutive games with an interception for a touchdown, 2 the only player in team history Only player in the NFL to have at least two interceptions returned 2 for a touchdown and at least two sacks 3 Interceptions, tied for fifth among safeties 7 Passes defensed, tied for sixth-most among NFL safeties JARVIS LANDRY One of two players in NFL to have gained at least 100 yards on rushing (107), 100 receiving (816), kickoff returns (255) and punt returns (252) 14 / WR Catch percentage, fourth-highest among receivers with at least 70 71.7 receptions over the last two years Of two receivers in the NFL to have a special teams touchdown (1 punt return 1 for a touchdown), rushing touchdown (1 rushing touchdown) and a receiving touchdown (4 receiving touchdowns) in 2015 Only player in NFL with a rushing attempt, reception, kickoff return, 1 punt return, a pass completion and a two point conversion in 2015 NDAMUKONG SUH 4 Passes defensed, tied for first among NFL defensive tackles 93 / DT Third-highest rated NFL pass rush interior defensive lineman 91.8 by Pro Football Focus Fourth-highest rated overall NFL interior defensive lineman 92.3 by Pro Football Focus 4 Sacks, tied for sixth among NFL defensive tackles 10 Stuffs, is the most among NFL defensive tackles 4 Pro Bowl selections following the 2010, 2012, 2013 and 2014 seasons TABLE OF CONTENTS GAME INFORMATION 4-5 2015 MIAMI DOLPHINS SEASON SCHEDULE 6-7 MIAMI DOLPHINS 50TH SEASON ALL-TIME TEAM 8-9 2015 NFL RANKINGS 10 2015 DOLPHINS LEADERS AND STATISTICS 11 WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN 2015/WHAT TO LOOK FOR AGAINST THE RAVENS 12 DOLPHINS-RAVENS OFFENSIVE/DEFENSIVE COMPARISON 13 DOLPHINS PLAYERS VS. -

Redskins Live on the Edge, Then Fall Off ST

NATIONALS THINKING BIGGER THAN ONCE THOUGHT POSSIBLE, C1 EXPANDED COVERAGE, R4: Replacement offi cials lose control Secondary exposed by Rams’ Amendola; Carriker, Orakpo add to injury woes 31 28 G AMEDAY MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 2012 ☆☆ washingtontimes.com/sports/football DOWN TO EARTH Big lead, Week 1 momentum go out window with loss BY RICH CAMPBELL THE WASHINGTON TIMES ST. LOUIS |The men who play professional foot- ball will tell you it is the most emotional of sports. That’s a byproduct of its physical nature and the machismo that inevitably accompanies that. This is the NFL, where the players are the biggest and fastest in the world. Fame and fortune only raise the stakes. Players also will tell you the retaliator usually is the one penalized. When emotions boil over on the fi eld, victory can be determined by poise and composure. When your opponent illegally hits you, how do you respond? That was on Joshua Morgan’s mind as he sat at his locker Sunday evening, towel wrapped around his waist, staring at his cellphone. For all the skir- mishes that occurred during and after plays in the Washington Redskins’ 31-28 loss to the St. Louis Rams, and for all the good and bad plays the Red- skins made while staying within reach of victory, one truth mattered more than any other. Morgan was the retaliator. And, of course, he was caught. The Redskins wide receiver was penalized 15 yards for throwing the ball at Rams cornerback Cortland Finnegan with 1:18 remaining in a 3-point game. -

April 22, 1995

all of whom believe that because that group is so April 22, 2016 deep, we're going to see teams in the first and second round kind of going after positions of need that aren't anywhere near as deep, like say wide NFL Network Analyst Mike receiver. Or if you think there are four offensive tackles in the drop off, you better go get that Mayock offensive tackle before you get your defensive tackle. But I've talked to an awful lot of teams over THE MODERATOR: Thank you for joining us the last couple of weeks, and he is especially with today on the second of two NFL Network NFL Draft those two trades to the quarterbacks happening, media conference calls. Joining me on the call I'm pretty psyched up for this draft. So let's open today is NFL Networks lead analyst for the 2016 this thing up and take some questions. NFL Draft, Emmy nominated Mayock. Before I turn it over to Mike for opening remarks and Q. Since Ronnie Stanley probably isn't questions, a few quick NFL media programming going to make it to the middle of the third notes around the 2016 NFL Draft. round when the Eagles pick again after taking a Starting Sunday, NFL Network will provide quarterback at number two, I'm curious what 71 hours of live draft week coverage. NFL you think are their best possible offensive Network's draft coverage will feature a record 19 tackle options if they go that route at number NFL team war room cameras, including the L.A. -

Essential Dynasty Cheat Sheet

The Essential Dynasty League Rankings Quarterbacks Running Backs (cont.) 1. Aaron Rodgers, GB 51. Jason Campbell, CHI 26. David Wilson, NYG (R) 76. Jason Snelling, ATL 2. Cam Newton, CAR 52. Chase Daniel, NO 27. Roy Helu, WAS 77. Marcel Reece, OAK 3. Drew Brees, NO 53. David Garrard, MIA 28. Kendall Hunter, SF 78. Kahlil Bell, CHI 4. Matthew Stafford, DET 53. Tyrod Taylor, BAL 29. Stevan Ridley, NE 79. Tim Hightower, WAS 5. Tom Brady, NE 54. Shaun Hill, DET 30. Isaiah Pead, STL (R) 80. Brandon Jacobs, SF 6. Andrew Luck, IND 55. Terrelle Pryor, OAK 31. Ronnie Hillman, DEN (R) 81. Danny Woodhead, NE 7. Matt Ryan, ATL 56. Stephen McGee, DAL 32. DeAngelo Williams, CAR 82. Dion Lewis, PHI 8. Eli Manning, NYG 57. BJ Coleman, GB (R) 33. Michael Turner, ATL 83. Dan Herron, CIN (R) 9. Robert Griffin III, WAS (R) 58. Colt McCoy, CLE 34. James Starks, GB 84. Cedric Benson, FA 10. Philip Rivers, SD 59. Vince Young, BUF 35. Fred Jackson, BUF 85. Vick Ballard, IND (R) 11. Tony Romo, DAL 60. Rex Grossman, WAS 36. Michael Bush, CHI 86. Ryan Grant, FA 12. Ben Roethlisberger, PIT 61. Luke McCown, NO 37. Jahvid Best, DET 87. Justin Forsett, HOU 13. Jay Cutler, CHI 62. Ricki Stanzi, KC 38. Donald Brown, IND 88. Joseph Addai, FA 14. Michael Vick, PHI 63. Matt Leinart, OAK 39. Shane Vereen, NE 89. Chris Ogbonnaya, CLE 15. Jake Locker, TEN 64. Jimmy Clausen, CAR 40. Shonn Greene, NYJ 90. Michael Smith, TB (R) 16. Sam Bradford, STL 65. -

Should America Continue to Encourage Its Youth to Participate

Coastal Carolina University CCU Digital Commons Honors College and Center for Interdisciplinary Honors Theses Studies Spring 5-15-2016 Managing a Crisis: Should America Continue to Encourage Its Youth to Participate in Football Given Recent Findings on Player Safety and Concussions Brock Matava Coastal Carolina University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/honors-theses Part of the Management Sciences and Quantitative Methods Commons Recommended Citation Matava, Brock, "Managing a Crisis: Should America Continue to Encourage Its Youth to Participate in Football Given Recent Findings on Player Safety and Concussions" (2016). Honors Theses. 8. https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/honors-theses/8 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College and Center for Interdisciplinary Studies at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MANAGING A CRISIS: SHOULD AMERICA CONTINUE TO ENCOURAGE ITS YOUTH TOPARTICIP ATE IN FOOTBALL GIVEN RECENT FINDINGS ON PLAYER SAFETY AND CONCUSSIONS SPRING2016 By: Brock Matava Major: Management Date: May 1, 2016 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Business Management In the Honors Program at Coastal Carolina University Abstract In recent years, more light has been shed on player safety issues when it comes to youth sports, football especially. The major emphasis of concern is on reducing concussion rates among our youth and an exposure to the potentially lifelong disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE}. Financially however, the National Football League (NFL}, the highest level of football anywhere in the world, is healthier than it has ever been. -

49Ers Hall of Fame

10 18 INSIDE 5 this ISSUE Charles Haley: | 5 The Man With 5 Rings Alumni Updates | 10 The 49ers Remember | 16 22 28 John Brodie: A Bay Area | 18 Legend from Preps to Pros The 49ers Museum | 22 Presented by Sony The Edward J. DeBartolo, Sr. | 28 49ers Hall of Fame Alumni Photos | 34 49ers New Coaching Staff | 36 36 2015 NFL Draft | 40 DEAR 49ERS ALUMNI, As you know, the offseason training program is now winding down. A lot of great work has been put in over the last few months by our players, coaches and staff, and we are all looking forward to getting the 2015 season started in late July. It is a very exciting time for everyone in our organization and we hope it is for our alumni as well. Every day we walk into the practice facility at 4949 Marie P. DeBartolo Way, we are reminded of the great tra- dition of this franchise and the people, such as our alumni, who have helped to write its proud history. It was important to this organization to reinforce our feelings of gratitude and appreciation for your contri- butions and continued support before the season gets underway. The dedication you have shown to this fran- chise and the sacrifices you and your families have made are certainly recognized and will never be forgotten. We would like to take this opportunity to congratulate Charles Haley on his upcoming induction into the Pro Foot- ball Hall of Fame and the Edward J. DeBartolo, Sr. 49ers Hall of Fame. In the game of football, acknowledge- ments such as those not only celebrate the great individual accomplishments of one man, but they also celebrate the contributions of those around him – his teammates and coaches. -

Samuel Pahlsson?ˉs Power Play Goal in the Finally Time to Lift The

Samuel Pahlsson?¡¥s power play goal in the finally time to lift the Ducks around going to be the Kings,nfl store, 2-1,all around the Tuesday good night at Honda Center. Bobby Ryan also scored a multi functional power play goal in your first amount of time enchanting going to be the Ducks, whose past six goals have can be bought everywhere in the going to be the an outlet play. They are 9-for-23 on the a power outlet play well over going to be the past six games The Ducks committed penalties within 22 a few moments concerning each other late everywhere over the the first lead-time and the Kings?¡¥ Kyle Quincey scored everywhere over the the two- man advantage to node it at 1 ahead of due date in the second. Rob Niedermayer added an bare thought out strategies goal as well as for Ducks. Defenseman Mark Mitera,baseball jersey builder,a multi functional first-round selection based on the Ducks in your 2006 NHL yard draft, has not ever necessarily chose to explore have an operation to explore repair lower - leg damage experienced as part of your University about Michigan?¡¥s season-opener Oct. 10,a multi functional Michigan Daily story said. The campus newspaper quoted the player?¡¥s father,personalized nhl jersey, Ken Mitera,cheap throwback nba jerseys, saying the family has do not made a multi functional decision everywhere in the skillfull course about action. Mark Mitera,nfl jersey sales,nba jersey numbers, five days too shy concerning his 21st birthday,could be the Wolverines captain. -

Miami Did Not Participate: S Yeremiah Bell (Toe),Nfl Giants Jersey,Nike

Miami Did not participate: S Yeremiah Bell (toe),nfl giants jersey,nike jerseys for nfl, T Marc Colombo (knee),nfl giants jersey, C Mike Pouncey (neck),custom hockey jerseys, LB Jason Taylor (hip) Sports Illustrated?¡¥s Peter King first reported the news during halftime of Thursday night?¡¥s season opener between Minnesota and New Orleans. King reported that Patriots owner Robert Kraft told him that a 4-year deal has been finalized with the teams franchise quarterback. The news comes at the end of an eventful day for Brady,authentic football jerseys,nike in the nfl, who was involved in a car accident early this morning on his way to Gillette Stadium for practice. By NFL.com Staff | Actor Ed O'Neill had a brief role as a defensive end for the Steelers. (Dan Steinberg/Associated Press) Summary: J.J. Watt can help a team in a lot of ways. He can play different spots across the line,sports jersey numbers, help on special teams blocking kicks and even do a Mike Vrabel impression as a receiving tight end. In his primary role on defense he can be a dominating presence as a five-technique defensive end in a 3-4. On the downside,nike custom jerseys,custom mlb jersey, while his ascension to top prospect is impressive,football jersey creator,syracuse basketball jersey, he was a Central Michigan tight end not that long ago. He is very much a work in progress. We Offer A Variety Of Cheap/Wholesale Nike NFL Jerseys,NHL Jerseys,michigan football jersey,MLB Jerseys,NBA Jerseys,NFL Jerseys,NCAA Jerseys,Custom Jerseys,personalized nfl football jerseys,Soccer Jerseys,Sports Caps etc, Wholesale Cheap Jerseys With Big Discount. -

Its Been an Top-Notch Season As Well As for Richard Seymour. ,Nfl Women

Its been an top-notch season as well as for Richard Seymour. ,nfl women s jersey Seymour The Oakland Raiders Pro Bowl guarding lineman was fined $30,football jersey sizes,000 on such basis as the NFL gorgeous honeymoons as well punching Miami offensive lineman Richie Incognito as part of your Dolphins 34-14 win upwards of Oakland all around the Sunday. Seymour was ejected as well as the offense. It perhaps be the additionally time all over the Seymours around three seasons on the Oakland -- person was acquired throughout the a multi functional trade to have New England everywhere over the September 2009 -- in your all of which your dog was ejected back and forth from a multi function game. Seymour has currently been fined,nfl home jersey, at least,sports jerseys, $60,000 as well as for offenses this season. Last season, Seymour was fined $25,cheap football jersey,000 after being ejected enchanting slapping and knocking to the ground Pittsburgh quarterback Ben Roethlisberger. In 2009,they was fined $10,nfl jersey monster,000 after your dog was ejected and for an offense against Cleveland fleeing back Jerome Harrison. Seymour is going to need thought out strategies careful or his fines not only can they continue for more information regarding grow; she or he may or may not eventually face a multi function brief time suspension if the infractions continue. Seymour has to be that a multi functional great player who may be the as aggressive as they are usually available He falls off the tone also the Oakland criminal,but your puppy is going to need keep his emotions in check much better He cant be of assistance going to be the Raiders if the affected person keeps getting ejected from games.NEW ORLEANS -- If Bill Cowher returns on investment for more information about coaching,nfl team jerseys,element ach and every if that's so may be the case as part of your NFC South. -

NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (4-3) at ST. LOUIS RAMS (3-4) Sunday, October 28, 2012, Wembley Stadium, Noon (CT) 2012 SCHEDULE RAMS, PATRIOTS SQUARE OFF in LONDON Sun

WEEK 8 NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (4-3) AT ST. LOUIS RAMS (3-4) Sunday, October 28, 2012, Wembley Stadium, Noon (CT) 2012 SCHEDULE RAMS, PATRIOTS SQUARE OFF IN LONDON Sun. 9/9 at Detroit L, 27-24 The St. Louis Rams will participate in the NFL’s Sun. 9/16 Washington W, 31-28 International Series for the first time as they face the New England Patriots at London’s Wembley Sun. 9/23 at Chicago L, 23-6 Stadium Sunday. The Rams will serve as the home Sun. 9/30 Seattle W, 19-13 team in this year’s International Series contest. Kickoff is scheduled for 5 p.m. locally, noon Central. Thurs. 10/4 Arizona W, 17-3 The Rams look to even their record at 4-4 on the Sun. 10/14 at Miami L, 17-14 season after falling to the Green Bay Packers last Sun. 10/21 Green Bay L, 30-20 week at the Edward Jones Dome. New England is coming off an overtime win over the Jets. Sun. 10/28 New England* Noon CBS Sun. 11/4 BYE The regular season series between St. Louis and New England is tied at 5-5. The two teams also met Sun. 11/11 at San Francisco 3:15 p.m. Fox in Super Bowl XXXVI, a thriller that New England Sun. 11/18 N.Y. Jets Noon CBS QB Sam Bradford won 20-17 on the final play of the game. Sun. 11/25 at Arizona 3:15 p.m. Fox BROADCAST INFORMATION Sun. 12/2 San Francisco Noon Fox TELEVISION RADIO Sun.