Artists' Video

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sixties Counterculture and Public Space, 1964--1967

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2003 "Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967 Jill Katherine Silos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Silos, Jill Katherine, ""Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations. 170. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/170 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Congratulations to All of the Winners & Finalists of the 2013 USA Best

Congratulations to all of the Winners & Finalists of The 2013 USA Best Book Awards! Categories are listed alphabetically. All finalists are of equal merit. Animals/Pets: General Winner Chasing Doctor Dolittle: Learning the Language of Animals by Con Slobodchikoff, PhD St. Martin's Press 978-0-312-61179-8 Finalist How to Change the World in 30 Seconds: A Web Warrior's Guide to Animal Advocacy Online by C.A. Wulff Barking Planet Productions 978-0978692889 Finalist Pee Where You Want: Man's Best Friend Talks Back! by Karen H. Thompson The Dottin Publishing Group 978-0-9847853-0-8 Animals/Pets: Narrative Non-Fiction Winner M.E. And My Shadow: Wisdom From A Fourlegged Master by Mary Ellen Weiland Shadow Press 978-0-9837443-1-3 Finalist Lessons from Rocky & His Friends: Pawprints on the Heart by Bradford P. Miller LFR Publishing 978-1-4793-5231-9 Anthologies: Non-Fiction Winner No Lumps, Thank You. A Bra Anthologie. Special Edition: Uplifting Stories of Breast Cancer Survival by Meg Spielman Peldo and Kim Wagner Schiffer Publishing 978-0-7643-4288-2 Finalist Essays for my Father: A Legacy of Passion, Politics, and Patriotism in Small-Town America by Richard Muti Richard Muti 978-0-9891482-0-7 Art: General Winner Flight of the Mind, Marcus C. Thomas, A Painter's Journey Through Paralysis by Leslee N. Johnson Lydia Inglett Publishing/Starbooks.biz 978-1-938417-04-7 Art: Instructional/How-To Winner Out There: Design, Art, Travel, Shopping by Maria Gabriela Brito Pointed Leaf Press 978-1938461033 Autobiography/Memoirs Winner IMPOSSIBLE ODDS: The -

Dial Vice President Quits Post; Seeks Deal for Own Book Imprint

Dial Vice President Quits Post; Seeks Deal for Own Book Imprint E. L. Doctorow has resigned & World, and the Seymour as publisher and vice president Lawrence books a Delacorte of the Dial Press, Inc., a sub- Press, another Dell subsidiary. sidiary of the Dell Publishing Some weeks ago, Mr. Doc- Company, to start his own book torow took leave from Dial to imprint And -devote more time complete hsis third novel, "The to writing. Book of Daniel," which will be In announcing his resigna- published by Random House tion, Mrs. Helen Meyer, presi- this fall. The book,hesaid, dent of the tow companies, Some weeks ago, Mr. Doc- praised Mr. Doctorow as "a torow took leave from Dial to most creative editor and pub- complete his third novel, "The lisher," and said a successor Book of Daniel," which will he would be named later. published by Random House Mr. Doctorow said he no this fall. The book, he said, is longer wanted to be responsible inspired by "a major political for the administrative duties of crime in the nineteen-fifties." his position, which he assumed He is also writing a manu- last August, succeeding Rich- script for young readers, "The ard W. Baron. Mr. Baron, a First Book of Revolution," to co-owner of Dial, sold his stock be published by Mr. Baron's to Dell and left to form his company. own publishing house. Mr. Doctor() joined Dial in Mr. Doctorow, whose au- 1964 as editor in chief after thors included Norman five years as an editor with James Baldwin and Howard New American Library. -

Random House, Inc. Booth #52 & 53 M O C

RANDOM HOUSE, INC. BOOTHS # 52 & 53 www.commonreads.com One family’s extraordinary A remarkable biography of The amazing story of the first One name and two fates From master storyteller Erik Larson, courage and survival the writer Montaigne, and his “immortal” human cells —an inspiring story of a vivid portrait of Berlin during the in the face of repression. relevance today. grown in culture. tragedy and hope. first years of Hitler’s reign. Random House, Inc. is proud to exhibit at this year’s Annual Conference on The First-Year Experience® “One of the most intriguing An inspiring book that brings novels you’ll likely read.” together two dissimilar lives. Please visit Booths #52 & 53 to browse our —Library Journal wide variety of fiction and non-fiction on topics ranging from an appreciation of diversity to an exploration of personal values to an examination of life’s issues and current events. With so many unique and varied Random House, Inc. Booth #52 & 53 & #52 Booth Inc. House, Random titles available, you will be sure to find the right title for your program! A sweeping portrait of Anita Hill’s new book on gender, contemporary Africa evoking a race, and the importance of home. world where adults fear children. “ . [A] powerful journalistic window “ . [A]n elegant and powerful A graphic non-fiction account of “ . [A] blockbuster groundbreaking A novel set during one of the most into the obstacles faced by many.” plea for introversion.” a family’s survival and escape heartbreaking symphony of a novel.” conflicted and volatile times in –MacArthur Foundation citation —Brian R. -

Chapter 8.Pdf

Bibliography APPENDIXBibliography C Appendix C contains a complete bibliography of all the books mentioned in the Start With the Arts lessons. Bibliography Copyright 2003, 2012 John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. May be reproduced for educational and classroom purposes only. Bibliography BIBLIOGRAPHY Aardema, Verna. Borreguita and the Coyote: A Tale from Ayutla, Mexico. Illus. by Petra Mathers. Knopf, 1991. Aardema, Verna. Bringing the Rain to Kapiti Plain. Illus. by Beatriz Vidal. Dial Books for Young Readers, 1992. Aardema, Verna. Who’s in Rabbit’s House: A Masai Tale. Illus. by Leo and Diane Dillon. Dial Books for Young Readers, 1992. Ada, Alma Flor. Gathering the Sun. Illus. by Simón Silva. Lothrop, Lee & Shepard, 1997. Adams, Georgie. Fish, Fish, Fish. Illus. by Brigitte Willgoss. Dial Books for Young Readers, 1993. Addabbo, Carole. Dina the Deaf Dinosaur. Illus. by Valentine. Hannacroix Creek Books, 1998. Adler, David A. Thomas Alva Edison: Great Inventor. Illus. by Lyle Miller. Holiday House, 1990. Aesop. The Tortoise and the Hare. Illus. by Paul Meisel. Simon & Schuster, 1998. Aliki. Digging up Dinosaurs. HarperCollins Trophy, 1988. Aliki. Dinosaur Bones. HarperCollins Trophy, 1990. Aliki. Feelings. William Morrow & Co., 1986. Aliki. Fossils Tell of Long Ago. HarperCollins Trophy, 1990. Aliki. Hush Little Baby. Simon & Schuster, 1972. Aliki. I’m Growing. HarperCollins Children’s Books, 1992. Aliki. Marianthe’s Story: Painted Words, Spoken Memories. Greenwillow Books, 1998. Aliki. My Feet. HarperCollins Children’s Books, 1992. Aliki. My Five Senses (Let’s Read and Find Out Books). T. Y. Crowell, 1989. Aliki. My Hands. T. Y. Crowell, 1990. Aliki. My Visit to the Aquarium. -

THINK TANK AESTHETICS THINK TANK AESTHETICS Midcentury Modernism, the Cold War, and the Neoliberal Present PAMELA M

THINK TANK AESTHETICS THINK TANK AESTHETICS Midcentury Modernism, the Cold War, and the Neoliberal Present PAMELA M. LEE The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2020 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Garamond Premier Pro and Trade Gothic by the MIT Press. Endpapers: Patricio Guzmán, still, Nostalgia de la luz, 2010. © Patricio Guzmán, Atacama Productions. Courtesy Icarus Films. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Lee, Pamela M., author. Title: Think tank aesthetics : midcentury modernism, the Cold War, and the neoliberal present / Pamela M. Lee. Description: Cambridge, MA : The MIT Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019017908 | ISBN 9780262043526 (hardcover : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Art–Political aspects–History–20th century. | Modernism (Aesthetics) | Research institutes. | Neoliberalism. Classification: LCC N72.P6 L44 2020 | DDC 701/.17–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019017908 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 d_r0 Contents Acknowledgments Introduction 1: Aesthetic Strategist 2: Pattern Recognition circa 1947 3: 1973; or, the Arche of Neoliberalism 4: Open Secret: The Work of Art between Disclosure and Redaction Coda Notes Index Plates List of figures Introduction 0.1 Robert McNamara, date and location unknown. Courtesy the Library of Congres… 0.2 Leonard McCombe, “A Valuable Bunch of Brains,” Life magazine, May 1959. Cou… 0.3 RAND Corporation, 1700 Main Street, Santa Monica, California. -

Oxford University at Exeter College, Oxford Shaye Areheart, Director Emma Skeels, Assistant Director

Columbia Columbia Publishing Course at Publishing Course Oxford University at Exeter College, Oxford Shaye Areheart, Director Emma Skeels, Assistant Director For Information Columbia Publishing Course A Professional The Graduate School of Journalism Columbia University Experience in the 2950 Broadway, MC 3801 • New York, NY 10027 Business of Publishing In the UK: Columbia Publishing Course 06 September - Exeter College • Turl Street Oxford • OX1 3DP 01 October, 2021 Tel. +1 212-854-1898 A Program of the E-mail: [email protected] Columbia University Graduate @columbiapubcrse https://journalism.columbia.edu/publishing School of Journalism The Columbia Publishing Course The Columbia Publishing Course does not discriminate among applicants or students on the basis of race, at Exeter College, Oxford, religion, age, gender, sexual orientation, is a twin of the book-publishing portion national origin, color, or disability. of the New York course. Columbia Publishing y Exeter College at Oxford. The Refectory and classrooms. Course areers in publishing have always attracted > Oxford has always been an important center of people with talent and energy and a love of publishing and learning. C reading. Those with a love of literature and > People who are certain book publishing is where language, a respect for the written word, an inquiring they intend to be after the course do not have to mind, and a healthy imagination are naturally drawn to endure the rigors of the magazine-digital portion of an industry that creates, informs, and entertains. the New York program. For many, publishing is more than a business; it is a > The course in New York is limited to 110 people, so vocation that constantly challenges and continuously Exeter enables us to help shepherd more people into educates. -

Of 37 MONTHLY ACCESSIONS LIST REPORT: February 01-28, 2007

MONTHLY ACCESSIONS LIST REPORT: February 01-28, 2007 Page 1 of 37 HOFSTRA UNIV MONTHLY ACCESSIONS LIST REPORT February 01-28, 2007 ZIH$ ARTS February 01-28, 2007 M3.1.S885 O3 1998 Stravinsky, Igor. Oedipus Rex ; Symphony of Psalms. London ; New York : Boosey & Hawkes, [1998] M452 .B29 1945 Bartok, Bela. The string quartets of Bela Bartok. New York : Boosey & Hawkes, c1945. M1500.C38 C36 2007 Cavalli, Pier Francesco. La Calisto. Middleton, Wis. : A-R Editions, c2007. M1520.S9 V47 1989 Stravinsky, Igor. The rite of spring. New York : Dover, 1989. ML102.O6 O6213 2000 Opera : composers, works, performers. English ed. Cologne : Konemann, c2000. ML421.R64 D3 1972 Dalton, David. Rolling Stones. New York, Amsco Music Pub. Co. [c1972] ML1092 .T38 1997 Theberge, Paul. Any sound you can imagine : making music/consuming technology. Hanover, NH : Wesleyan University Press : University Press of New England, 1997. ML3477 .J46 2005 Jenness, David. Classic American popular song : the second half-century, 1950-2000. New York : Routledge, 2006. ML3549 .P57 2005 Pisani, Michael. Imagining native America in music. New Haven : Yale MONTHLY ACCESSIONS LIST REPORT: February 01-28, 2007 Page 2 of 37 University Press, c2005. MT892 .E45 2006 Elliott, Martha. Singing in style : a guide to vocal performance practices. New Haven : Yale University Press, c2006. N72.M3 V58 2005 The visual mind II. Cambridge, Mass. : MIT Press, c2005. N6494.V53 C75 1995 Critical issues in electronic media. Albany : State University of New York Press, c1995. N6537.H4 E53 2006 Encountering Eva Hesse. Munich ; New York : Prestel, c2006. N6537.S523 A4 2006 Brock, Charles. Charles Sheeler : across media. -

Columbia Publishing Course Publishing Formerly the Radcliffe Publishing Course Course

Columbia Columbia Publishing Course Publishing formerly the Radcliffe Publishing Course Course For Information Shaye Areheart, Director Emma Skeels, Assistant Director A Professional Columbia Publishing Course Experience in The Graduate School of Journalism Columbia University the Business 2950 Broadway, MC 3801 of Publishing New York, NY 10027 Tel. 212-854-1898 E-mail: [email protected] @columbiapubcrse https://journalism.columbia.edu/publishing June 14 – July 23, 2020 The Columbia Publishing Course does not discriminate Columbia University among applicants or students on the basis of race, Graduate School of Journalism religion, age, gender, sexual orientation, national origin, color, or disability. New York City Columbia Publishing Course areers in publishing have always attracted people with talent and energy and a love of Creading. Those with a love of literature and language, a respect for the written word, an inquiring mind, and a healthy imagination are naturally drawn to an industry that creates, informs, and entertains. y The class of 2019 For many, publishing is more than a business; it is a vocation that constantly challenges and continuously educates. Choosing a career in publishing is a logical The Publishing Course allows students to compare way to combine personal and professional interests for book, magazine, and digital publishing, which helps people who have always worked on school publications, them determine their career preferences. During the first spent hours browsing in bookstores and libraries, or weeks, the course concentrates on book publishing— subscribed to too many magazines. from manuscript to bound book, from bookstore sale The Columbia Publishing Course was originally to movie deal. Students study every element of the founded in 1947 at Radcliffe College in Cambridge, process: manuscript evaluation, agenting, editing, design, Massachusetts, where it thrived as the Radcliffe production, publicity, sales, e-books, and marketing. -

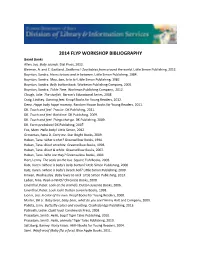

2014 FLYP WORKSHOP BIBLIOGRAPHY Board Books Allen, Joy

2014 FLYP WORKSHOP BIBLIOGRAPHY Board Books Allen, Joy. Baby sounds. Dial Press, 2012. Bleiman, A. and C. Eastland. ZooBorns!: Zoo babies from around the world. Little Simon Publishing, 2012. Boynton, Sandra. Horns to toes and in between. Little Simon Publishing, 1984. Boynton, Sandra. Moo, baa, la la la! Little Simon Publishing, 1982. Boynton, Sandra. Belly button book. Workman Publishing Company, 2005. Boynton, Sandra. Tickle Time. Workman Publishing Company, 2012. Clough, Julie. The starfish. Barron's Educational Series, 2008. Craig, Lindsey. Dancing feet. Knopf Books for Young Readers, 2012. Dena. Happi baby happi mommy. Random House Books for Young Readers, 2011. DK. Touch and feel: Tractor. DK Publishing, 2011. DK. Touch and feel: Bathtime. DK Publishing, 2009. DK. Touch and feel: Things that go. DK Publishing, 2009. DK. Farm peekaboo! DK Publishing, 2007. Fox, Mem. Hello baby! Little Simon, 2012. Grossman, Rena D. Carry me. Star Bright Books, 2009. Hoban, Tana. What is that? Greenwillow Books, 1994. Hoban, Tana. Black on white. Greenwillow Books, 1993. Hoban, Tana. Black & white. Greenwillow Books, 2007. Hoban, Tana. Who are they? Greenwillow Books, 1994. Hort, Lenny. The seals on the bus. Square Fish Books, 2003. Katz, Karen. Where is baby’s belly button? Little Simon Publishing, 2000. Katz, Karen. Where is baby’s beach ball? Little Simon Publishing, 2009. Kirwan, Wednesday. Baby loves to rock. Little Simon Publishing, 2013. Laden, Nina. Peek-a-WHO? Chronicle Books, 2000. Linenthal, Peter. Look at the animals. Dutton Juvenile Books, 2006. Linenthal, Peter. Look look! Dutton Juvenile Books, 1998. Lionni, Leo. A color of his own. Knopf Books for Young Readers, 2000. -

CONTENTS Letter from and We Were the Last Ones Still Talking

the pitch spring 2014 The Newsletter for the Association of Authors' Representatives CONTENTS LETTER FROM and we were the last ones still talking. I THE PRESIDENT felt as if I had had a primer on the last 1. LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT fifty years in this business. Michigan-born Carole always 3. THE RISE OF MASS MARKET e in the American agent thought she would follow her father 4. BIG MOVES: SPOTLIGHT ON Wcommunity have suffered way too many into law, then considered looking for EDITORS' NEW POSITIONS sad losses in the past couple of years. a position on Wall Street, and moved How we miss the genial temperament to New York City after college in the 5. LOIS WALLACE, AN ORIGINAL of Owen Laster, who seemed to know mid-1960s only to find that it appeared 6. NEW FINANCING POSSIBILITIES everyone else at the Four Seasons impossible for a young woman to find FOR THEATRICAL PRODUCTIONS when we met for a group lunch there; a good job on Wall Street. To pay the 6. COMMITTEE REPORT: the gentlemanly warmth of Carl rent, she took a job as a copy editor at INTERNATIONAL Brandt; the droll seriousness of Robert Holt, Rinehart and Winston, and found 7. CONTRIBUTORS Lescher. I figure that Wendy Weil herself copyediting books such as “The and Lois Wallace, the best of friends Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison. Staff 8. WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW IF in life, are avidly discussing books, changes left her head of the copyediting YOU'RE BUILDING A NEW AGENCY WEBSITE fashion, and the latest gossip in the department. -

Booknet Indie Bestseller August 24 to August 30, 2020

INDEPENDENT BESTSELLER LIST OVERALL BESTSELLERS August 24 – August 30, 2020 Title Author ISBN Publisher List Price How to Be an Antiracist Kendi, Ibram X. 9780525509288 Random House Publishing Group; 36 One World/Ballantine Indians on Vacation King, Thomas 9781443460545 HarperCollins Canada, Limited 32.99 Antiracist Baby Board Book Kendi, Ibram X.; 9780593110416 Penguin Young Readers Group; 11.99 Lukashevsky, Ashley Kokila White Fragility DiAngelo, Robin 9780807047415 Beacon Press 22 So You Want to Talk about Race Oluo, Ijeoma 9781580058827 Basic Books; Seal Press 22.99 A History of My Brief Body Belcourt, Billy-Ray 9780735237780 Penguin Canada; Hamish Hamilton 25 Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, Reynolds, Jason; 9780316453691 Little, Brown Books for Young 23.99 and You Kendi, Ibram X. Readers The Pull of the Stars Donoghue, Emma 9781443461788 HarperCollins Canada, Limited; 33.99 Harper Avenue Too Much and Never Enough Trump, Mary L. 9781982141462 Simon & Schuster, Incorporated 37 Untamed Doyle, Glennon 9781984801258 Random House Publishing Group; 37 The Dial Press Braiding Sweetgrass Kimmerer, Robin 9781571313560 Milkweed Editions 26.95 Wall Something Happened in Our Celano, Marianne; 9781433828546 American Psychological 30.22 Town Collins, Marietta; Association; Magination Press Hazzard, Ann; Zivoin, Jennifer Normal People Rooney, Sally 9780735276499 Knopf Canada; Vintage Canada 21 American Dirt Cummins, Jeanine 9781250754080 Flatiron Books 23.99 Songs for the End of the World Nawaz, Saleema 9780771072574 McClelland & Stewart 24.95 This