PRODUCT RULES for PACKAGED RETAIL PRODUCTS: WHY, WHEN, HOW? Discussion Paper in the Context of the Prips Regulation Proposal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ex-Post Structured Product Returns: Index Methodology and Analysis

Ex-post Structured Product Returns: Index Methodology and Analysis Geng Deng, PhD, CFA, FRM∗ Tim Dulaney, PhD, FRMy;z Tim Husson, PhD, FRMx;z Craig McCann, PhD, CFA{ Mike Yan, PhD, FRMk August 20, 2014 Abstract The academic and practitioner literature now includes numerous studies of the substantial issue date mispricing of structured products but there is no large scale study of the ex- post returns earned by US structured product investors. This paper augments the current literature by analyzing the ex-post returns of over 20,000 individual structured products issued by 13 brokerage firms since 2007. We construct our structured product index and sub- indices for reverse convertibles, single-observation reverse convertibles, tracking securities, and autocallable securities by valuing each structured product in our database each day. The ex-post returns of US structured products are highly correlated with the returns of large capitalization equity markets in the aggregate but individual structured products generally underperform simple alternative allocations to stocks and bonds. The observed underperformance of structured products is consistent with the significant issue date under- pricing documented in the literature. ∗Director of Research, Securities Litigation and Consulting Group. yFinancial Analyst, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, [email protected]. zThe Securities and Exchange Commission, as a matter of policy, disclaims responsibility for any private pub- lication or statement by any of its employees. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Commission or of the author's colleagues upon the staff of the Commission. xFinancial Analyst, U.S. -

Analysis of Securitized Asset Liquidity June 2017 an He and Bruce Mizrach1

Analysis of Securitized Asset Liquidity June 2017 An He and Bruce Mizrach1 1. Introduction This research note extends our prior analysis2 of corporate bond liquidity to the structured products markets. We analyze data from the TRACE3 system, which began collecting secondary market trading activity on structured products in 2011. We explore two general categories of structured products: (1) real estate securities, including mortgage-backed securities in residential housing (MBS) and commercial building (CMBS), collateralized mortgage products (CMO) and to-be-announced forward mortgages (TBA); and (2) asset-backed securities (ABS) in credit cards, autos, student loans and other miscellaneous categories. Consistent with others,4 we find that the new issue market for securitized assets decreased sharply after the financial crisis and has not yet rebounded to pre-crisis levels. Issuance is below 2007 levels in CMBS, CMOs and ABS. MBS issuance had recovered by 2012 but has declined over the last four years. By contrast, 2016 issuance in the corporate bond market was at a record high for the fifth consecutive year, exceeding $1.5 trillion. Consistent with the new issue volume decline, the median age of securities being traded in non-agency CMO are more than ten years old. In student loans, the average security is over seven years old. Over the last four years, secondary market trading volumes in CMOs and TBA are down from 14 to 27%. Overall ABS volumes are down 16%. Student loan and other miscellaneous ABS declines balance increases in automobiles and credit cards. By contrast, daily trading volume in the most active corporate bonds is up nearly 28%. -

RETAIL Structured Solutions. You Have a Right to Expect Stability and Excellence from Product Providers

RETAIL STRUCTURED SOLUTIONS RETAIL Structured Solutions. You have a right to expect stability and excellence from product providers. Since 1995 we have managed all aspects of structured products. This is the expertise we bring to WE would reallY liKE to worK witH looking after over 250,000 customers. You and APPreciate Your FeedBacK. This is not a consumer advertisement. It is intended for professional financial advisers and should not be relied Our team are always on hand to talk to you about your needs, with a dedicated upon by private investors or any other persons. Structured Solutions team to support your strategy and future goals. We appreciate that turbulent markets have meant that professional investors such as yourselves are keener than ever to work with a stable, established company, who can offer you the assurance you need. CONTACT US Please contact your Legal & General representative or the Retail Structured Solutions team at [email protected]. Details of our latest products can be found at www.landgstructuredproducts.com This document should not be taken as an invitation to deal in any Legal & General investment including the stated investment. If investors cash in any or all of their investment early then they may get back less than they invest. Legal & General (Portfolio Management Services) Limited Registered in England No. 2457525 Registered office: One Coleman Street, London EC2R 5AA Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. CW4018 07/13 H142530 2 RETAIL STRUCTURED SOLUTIONS LEGal & General GrouP. Legal & General is a leading provider of risk, savings thriving and that Legal & General’s double-digit sales and investment management products in the UK. -

Best Practices for Structured Products Designed for Individual Investors

ISDA® LIBA Structured Products: Principles for Managing the Distributor- Individual Investor Relationship The distributor-individual investor relationship should deliver fair treatment of the individual investor. Individual investors need to take responsibility for their investment goals and to stay informed about the risks and rewards of their investments. Distributors can play a key role in helping them achieve these objectives. In this document, an "investor" means a retail investor who is not an institution, a professional, or a sophisticated investor, and a "distributor" refers to any institution or entity that markets or sells retail structured products directly to an individual investor. This will include an issuer of a retail structured product that markets or sells the same directly to individual investors. In light of the increased interest in structured products as part of individual investors’ investment and asset allocation strategies, it is important for firms to keep these principles in mind in their dealings with individual investors in structured products. These principles complement and should be read in conjunction with our recently released, “Retail Structured Products: Principles for Managing the Provider-Distributor Relationship,” available at the websites of the five sponsoring associations1, which focus on the relationship between manufacturers and distributors. These principles apply to the relationship between the distributor and the individual investor. Although these principles are non-binding (being intended -

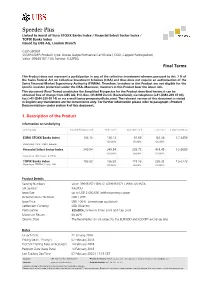

Speeder Plus Linked to Worst of Euro STOXX Banks Index / Financial Select Sector Index / TOPIX Banks Index Issued by UBS AG, London Branch

Speeder Plus Linked to worst of Euro STOXX Banks Index / Financial Select Sector Index / TOPIX Banks Index Issued by UBS AG, London Branch Cash settled SVSP/EUSIPA Product Type: Bonus Outperformance Certificate (1330, Capped Participation) Valor: 39945157 / SIX Symbol: KAZPDU Final Terms This Product does not represent a participation in any of the collective investment schemes pursuant to Art. 7 ff of the Swiss Federal Act on Collective Investment Schemes (CISA) and thus does not require an authorisation of the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA). Therefore, Investors in this Product are not eligible for the specific investor protection under the CISA. Moreover, Investors in this Product bear the issuer risk. This document (Final Terms) constitutes the Simplified Prospectus for the Product described herein; it can be obtained free of charge from UBS AG, P.O. Box, CH-8098 Zurich (Switzerland), via telephone (+41-(0)44-239 47 03), fax (+41-(0)44-239 69 14) or via e-mail ([email protected]). The relevant version of this document is stated in English; any translations are for convenience only. For further information please refer to paragraph «Product Documentation» under section 4 of this document. 1. Description of the Product Information on Underlying Underlying(s) Initial Underlying Level Strike Level Kick-Out Level Cap Level Conversion Ratio EURO STOXX Banks Index 136.13 136.13 81.68 163.36 1:7.3459 100.00% 60.00% 120.00% Bloomberg: SX7E / Valor: 846500 Financial Select Sector Index 349.54 349.54 209.72 419.45 -

An Overview of Hedge Funds and Structured Products: Issues in Leverage and Risk

An Overview of Hedge Funds and Structured Products: Issues in Leverage and Risk Adrian Blundell-Wignall With their high share of trading turnover, hedge funds play a critical role in providing liquidity for mis-priced assets, particularly when large volumes are traded in thin markets – thereby reducing volatility. This activity is particularly important, given the rapid growth in volume of new-generation structured products issued by investment banks. Hedge fund leverage estimated via an induction technique suggests a leverage ratio that must be above 3 (versus total AUM of USD 1.4 trillion). Gearing is required to boost returns where low risk and low return styles are implemented. Investment banks are well capitalised against hedge fund exposure. “Structured products” are one of the fastest growing areas in the financial services industry, and may already be over half of the notional size of the hedge fund industry (AUM plus leverage). These products, constructed by investment banks, are extremely complex using synthetic option replication techniques, and offering a variety of guarantees in returns. They are sold to retail, private banking and institutional clients. Hedge funds help reduce volatility risk for investment banks in supplying these products. Structured products are passive in nature (unlike hedge fund active styles), focusing on providing returns for different risk profiles of clients. These products have not been tested when major anomalies in volatility arise. They are highly exposed to downward price gaps in the „risky‟ assets used in their construction. Considering the potential for such a crisis scenario, two major policy conclusions emerge: The importance of (1) stress testing of investment banks‟ balance sheets; and, (2) given the large retail market segment, consumer education and protection. -

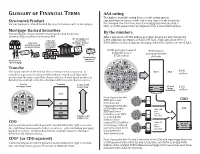

GLOSSARY of FINANCIAL TERMS

GLOSSARY oF FINANCIAL TERMS AAA rating The highest available rating from a credit rating agency, Structured Product representing the lowest credit risk of any class of debt securities. For our purposes, a bond backed by a pool of assets, such as mortgages. For example, the AAA tranches of a mortgage-backed security, a CDO, or a CDO squared are the highest rated, lowest risk tranches. Mortgage-Backed Securities The mortgages are pooled into Mortgage-Backed Securities. By the numbers Investors buy tranches of the securities Take a hypothetical $750 million mortgage-backed security backed by The mortgages are Financial pooled into 5,000 subprime mortgages of $150,000 each. Typically, about 80% or Financial institution Mortgage-Backed $600 million of these subprime mortgage-backed securities are rated AAA. institutions fund holds many Securities home purchases mortgages AA 5,000 mortgage loans of $750 million $150,000 each = mortgage-backed $750 million Investors buy security tranches of Homeowners securites sign mortgage Tranche The word tranche is French for slice, section, series, or portion. A 80% AAA $600 tranche is a portion of a structured product created such that each million divided into multiple tranches that have different risk characteristics. portion hasPool the of same cash �low characteristics.Tranches A structuredLower product yield is mortgage loans Lower risk AA and $150 20% lower tranches million AAA Now, if you take the CDO BBB and lower AAA AA tranches and repackage them into AAA A a CDO with other other AA BBB and lower and BBB tranches, over 83% AAA lower BB- Higher yield tranches unrated Higher risk or nearly $630 million of the CDO original $750 million other AA AA and A structured product which gives the bond holders the right to receive in mortgage-related and lower lower tranches the assets has now been AAA tranches backed securities. -

Financial Instruments Structured Products Handbook ˆ Oesterreichische Nationalbank

≈√ Oesterreichische Nationalbank Financial Instruments Structured Products Handbook ˆ Oesterreichische Nationalbank Financial Instruments Structured Products Handbook Structured capital market products — including ever-new ones — have become increasingly complex in recent years. For market participants to be able to evaluate and control the risks involved, they must be well-grounded in the intricacies of these innovative instruments as well as in adequate valuation techniques. This publication is meant to provide all interested market participants with a reference work about the valuation and replication of the struc- tured bond products most widely traded in Austria. A partner institution of the Austrian credit institutions, the OeNB offers this service to all market players to ensure transparency. The first part of the handbook deals with structured bonds whose payoff properties depend on interest rate movements, and the following two parts focus on products whose payoff characteristics are shaped by equity prices and foreign exchange rates. The replication techniques presented in this handbook are meant to serve as exemplary approaches, e.g. to reporting the Austrian interest rate risk statistics or computing the regulatory capital requirement. This ensures increased transparency and objectivity during audits. Ultimately, the Oesterreichische Nationalbank aims to strengthen the confidence in the Austrian financial marketplace and to contribute in particular in the light of Basel II to its stability and competitiveness. Univ.-Doz. Mag. -

Are Structured Products Suitable for Retail Investors? I. Introduction

Are Structured Products Suitable for Retail Investors? Craig McCann, PhD, CFA and Dengpan Luo, PhD, CFA1 Equity-linked notes - a type of structured product - are securities issued by brokerage firms and traded in the secondary markets like shares of common stock. These investments offer part of the upside from owning stocks but limit nominal losses if held until maturity. Once sold only to sophisticated investors, structured products are increasingly being sold to unsophisticated retail investors. Equity-linked notes are difficult to evaluate and monitor, have high hidden costs and are illiquid. They are therefore virtually never suitable for unsophisticated investors. I. Introduction Sales of structured products have soared in recent years as brokerage firms have found a retail market for products once sold only to sophisticated investors. According to the Structured Products Association – a trade group representing issuers and vendors – almost $50 billion of structured products were sold in 2005.2 Structured products can be too complex and opaque for retail investors and registered representatives to understand. This complexity and opaqueness allows structured products to survive in the marketplace despite their marked inferiority to traditional portfolios of stocks and bonds. The NASD has taken notice. In the current investment environment, investors and brokers are increasingly turning to alternatives to conventional equity and fixed- income investments in search of higher returns or yields. Such products, including … structured notes … are often complex or have unique features that may not be fully understood by the retail customers to whom they are frequently offered, or even by the brokers who recommend them. Some appear to offer benefits to investors that are already available in the market in the form of less risky, less complicated, or less costly products, prompting concerns about suitability and potential conflicts of interest. -

Retail Structured Products the Latest Regulatory Developments

Retail Structured Products The latest regulatory developments Ash Saluja, Simon Morris & Michael Cavers 26 June 2014 Looking at … 1. What the current rules are for manufacturing, distributing and advising on retail structured products 2. How these rules are changing 3. Recent documentation changes – Prospectus Directive 4. Enforcement and Supervision 2 UK/EU regulatory background − Focus of EU regulation (e.g. Markets in Financial Instruments Directive) had been on the sales process rather than on product manufacture − Notable exceptions in the funds sector (i.e. UCITS funds) and for some aspects in relation to transferable securities (i.e. Prospectus Directive regime) − Very light touch on deposit products due to capital protection and (previous) confidence on solvency of banks − Completely different EU regulatory regime for sale of insurance products (Insurance Mediation Directive) − UK regime applies many similar rules to “designated investments” (includes securities/investment products and life insurance products with an investment element) − Changes to the rules now very much driven by EU reforms, which are focused on manufacturers as well as distributors 3 Policy drivers for change − “Patchwork of uncoordinated regulation” (MiFID, IMD, UCITS, PD) – need for harmonisation across sectors − Minimise discretions available to Member States to reduce differences in rules between jurisdictions − Market and technological developments have outpaced MiFID I, undermining the level playing field − The financial crisis has challenged previous -

Structured Products at Janney Montgomery Scott

INVESTOR EDUCATION: INVESTMENTS STRUCTURED PRODUCTS AT JANNEY MONTGOMERY SCOTT Structured investments are debt securities derived from or based on a single security, basket of securities, index, commodity, foreign currency, or other asset classes. Janney offers two primary types of structured products—Market-Linked Certificates of Deposit (MLCDs) and Structured Notes. PRODUCT HIGHLIGHTS It is important for any investor to understand the features and risks of structured products before investing. Those features Structured products are a hybrid between two asset and risks are described in the prospectus. Credit quality of classes. Typically issued as an unsecured corporate bond the issuer, performance of the selected asset class, product or certificate of deposit with a fixed term, they include structure, liquidity, pricing, and tax treatment are important a derivative component whose cash flow and value are considerations when purchasing such an investment. determined from performance of another underlying investment or asset class. Structured products or market-linked investments: JANNEY’S STRUCTURED PRODUCTS • Can be purchased through an initial offering or in a Janney offers: limited secondary market. • Market-Linked CDs • Are issued as a bond or certificate of deposit (CD) with a fixed term or maturity. • Structured Notes • Have a specified underlying investment, the performance of which will determine cash flow, MARKET-LINKED CDS value, and investment return. Overview May include varying levels of capital “protection,” but • Market-Linked Certificates of Deposit (MLCDs) are are also subject to the risk that the issuer defaults or the structured products whose performance is largely based investment is not held to maturity, which may result in on one or more underlying securities or financial indexes. -

Structured Derivatives Valuation

Structured Derivatives Valuation Ľuboš Briatka Praha, 7 June 2016 Global financial assets = 225 trillion USD Size of derivatives market = 710 trillion USD BIS Quarterly Review, September 2014 Size of derivatives market • The value of the world's financial assets—including all stock, bonds, and bank deposits — is about 225 trillion USD • Over the counter derivatives market has an estimated size of about 710 trillion USD How can the derivatives market be worth more than 3 times the world's total financial assets? Financial Instruments - definition A financial instrument is any contract that gives rise to a financial asset of one entity and a financial liability or equity instrument of another entity Financial instruments Primary Derivatives financial instruments Examples Examples assets, liabilities, forwards/futures, options, equities, loans swaps Derivatives A derivative is a financial instrument with all 3 of the following characteristics: • its value changes in response to a change in a specified underlying (e.g. interest rate, financial instrument price, commodity price, foreign exchange rate, index of prices or rates, credit rating or credit index) • it requires no or very small initial net investment (when a derivative contract originates, the entity does not pay or collect the notional amount) • it is settled at a future date (the period from the trade date of the derivative transaction to the settlement date is longer than for spot transactions, i.e. longer that the ordinary settlement period for standard transactions) Why derivatives There is not a single investment bank which does not have a derivatives desk. Moreover, now even some non-financial institutions have their own derivatives analysts.