VISUAL MORPHOLOGY in DUTCH and FLEMISH COMICS 1 It Ain't

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

|||GRATIS||| Het Boemerangeffect Ebook

HET BOEMERANGEFFECT GRATIS EBOOK Auteur: Merho Aantal pagina's: 48 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: 2007-12-14 Uitgever: Standaard Uitgeverij EAN: 9789002224461 Taal: nl Link: Download hier Het boemerangeffect - De Kiekeboes Oude liefde roest niet, zegt het spreekwoord en Het Boemerangeffect de familie Kiekeboe krijgt ermee te maken. Dit keer staat er geen oud lief van Marcel voor de deur, maar Snoop Winckel, de Australische ex van Charlotte. Wanneer hij hoort dat Marcel een didgeridoo wil kopen, nodigt Snoop het hele gezin uit om een rondreis door Het Boemerangeffect te maken, op zijn kosten dan nog wel! Het is duidelijk dat er een re. Het is duidelijk dat er een reukje aan dit hele avontuur zit. Dit vermoeden wordt bevestigd wanneer twee ongure types 'toevallig' overal opduiken waar Snoop en zijn gasten verblijven Merho, pseudoniem van Robert Carolus Wilhelmina Rob Merhottein Antwerpen, Het Boemerangeffect oktoberis een Belgische stripauteur, die voornamelijk gekend is voor zijn strip De Kiekeboes. Merho groeide op in de Seefhoek, een wijk van Antwerpen. Aanvankelijk wilde hij komiek worden, maar Het Boemerangeffect koos dan al op jonge leeftijd Het Boemerangeffect striptekenaar te worden. Daarom bezocht hij meermaals de striptekenaars Bob Mau en Pom voor advies. Merho tekende tijdens zijn middelbareschooltijd zijn eerste strips. Een andere gagstrip, Zoz en Zef, verscheen in in het tijdschrift Jong Caritas. Vervolgens studeerde Merho Het Boemerangeffect grafiek aan de Sint-Lukashogeschool in Brussel. Na zijn studies begon hij in te werken bij Studio Het Boemerangeffect waar hij ter vervanging van Eduard De Rop de strip Jerom inktte. In o… Lees verder op Wikipedia. -

British Library Conference Centre

The Fifth International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference 18 – 20 July 2014 British Library Conference Centre In partnership with Studies in Comics and the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics Production and Institution (Friday 18 July 2014) Opening address from British Library exhibition curator Paul Gravett (Escape, Comica) Keynote talk from Pascal Lefèvre (LUCA School of Arts, Belgium): The Gatekeeping at Two Main Belgian Comics Publishers, Dupuis and Lombard, at a Time of Transition Evening event with Posy Simmonds (Tamara Drewe, Gemma Bovary) and Steve Bell (Maggie’s Farm, Lord God Almighty) Sedition and Anarchy (Saturday 19 July 2014) Keynote talk from Scott Bukatman (Stanford University, USA): The Problem of Appearance in Goya’s Los Capichos, and Mignola’s Hellboy Guest speakers Mike Carey (Lucifer, The Unwritten, The Girl With All The Gifts), David Baillie (2000AD, Judge Dredd, Portal666) and Mike Perkins (Captain America, The Stand) Comics, Culture and Education (Sunday 20 July 2014) Talk from Ariel Kahn (Roehampton University, London): Sex, Death and Surrealism: A Lacanian Reading of the Short Fiction of Koren Shadmi and Rutu Modan Roundtable discussion on the future of comics scholarship and institutional support 2 SCHEDULE 3 FRIDAY 18 JULY 2014 PRODUCTION AND INSTITUTION 09.00-09.30 Registration 09.30-10.00 Welcome (Auditorium) Kristian Jensen and Adrian Edwards, British Library 10.00-10.30 Opening Speech (Auditorium) Paul Gravett, Comica 10.30-11.30 Keynote Address (Auditorium) Pascal Lefèvre – The Gatekeeping at -

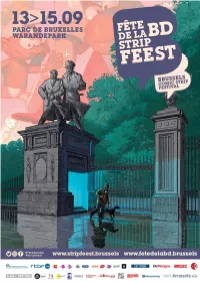

Bruxelles, Capitale De La Bande Dessinée Dossier Thématique 1

bruxelles, capitale de la bande dessinée dossier thématique 1. BRUXELLES ET LA BANDE DESSINÉE a. Naissance de la BD à Bruxelles b. Du héros de BD à la vedette de cinéma 2. LA BANDE DESSINÉE, PATRIMOINE DE BRUXELLES a. Publications BD b. Les fresques BD c. Les bâtiments et statues incontournables d. Les musées, expositions et galeries 3. LES ACTIVITÉS ET ÉVÈNEMENTS BD RÉCURRENTS a. Fête de la BD b. Les différents rendez-vous BD à Bruxelles c. Visites guidées 4. SHOPPING BD a. Adresses b. Librairies 5. RESTAURANTS BD 6. HÔTELS BD 7. CONTACTS UTILES www.visitbrussels.be/comics BRUXELLES EST LA CAPITALE DE LA BANDE DESSINEE ! DANS CHAQUE QUARTIER, AU DÉTOUR DES RUES ET RUELLES BRUXELLOISES, LA BANDE DESSINÉE EST PAR- TOUT. ELLE EST UNE FIERTÉ NATIONALE ET CELA SE RES- SENT PARTICULIÈREMENT DANS NOTRE CAPITALE. EN EFFET, LES AUTEURS BRUXELLOIS AYANT CONTRIBUÉ À L’ESSOR DU 9ÈME ART SONT NOMBREUX. VOUS L’APPRENDREZ EN VISITANT UN CENTRE ENTIÈREMENT DÉDIÉ À LA BANDE DESSINÉE, EN VOUS BALADANT AU CŒUR D’UN « VILLAGE BD » OU ENCORE EN RENCON- TRANT DES FIGURINES MONUMENTALES ISSUES DE PLUSIEURS ALBUMS D’AUTEURS BELGES… LA BANDE DESSINÉE EST UN ART À PART ENTIÈRE DONT LES BRUX- ELLOIS SONT PARTICULIÈREMENT FRIANDS. www.visitbrussels.be/comics 1. BRUXELLES ET LA BANDE DESSINEE A. NAISSANCE DE LA BD À BRUXELLES Raconter des histoires à travers une succession d’images a toujours existé aux quatre coins du monde. Cependant, les spéciali- stes s’accordent à dire que la Belgique est incontournable dans le milieu de ce que l’on appelle aujourd’hui la bande dessinée. -

De Lustige Kapoentjes Integraal Gratis Epub, Ebook

DE LUSTIGE KAPOENTJES INTEGRAAL GRATIS Auteur: Bouden Tom Aantal pagina's: 120 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: none Uitgever: none EAN: 9789491466434 Taal: nl Link: Download hier De Lustige Kapoentjes 2 De humoristische familiestripauteur is niet uit het nieuws te slaan. Aflevering verscheen in 't Kapoentje nummer 20 op 18 mei Van onze medewerker Onlangs opende een tentoonstelling in het Brusselse Marc Sleen Museum, Nero figureert in het Belgische paviljoen op de wereldtentoonstelling in Sjanghai en een exemplaar van het zeldzame Biz Vandaag om 5 miljoen euro voor maatwerkbedrijven die inzetten op circulaire economie Gisteren om Protest tegen veelvraat Amazon zwelt wereldwijd aan. Beroemd en Bizar Vandaag om Video Fransen maken zich vrolijk over verstrooide premier. De rijzende ster van de PS Hij is de nummer 3 van de PS, slaagde er tot verbazing van velen in de Nethys- stal uit te mesten en Waarom de manager van Helmut Lotti zijn centen in een kalverstal steekt In de grensstreek met Nederland verrijzen opvallend grote kalverstallen. Een mijlpaal voor Het journaal. EVP-familie beleeft week van de gêne Een Hongaars ex-Europarlementslid en de Bulgaarse premier gingen deze week met de billen bloot. Hiervoor sturen wij u een afhaal uitnodiging. Klik hier voor een routebeschrijving naar onze winkel. Sleen, Marc spring naar: Curiosa uitgaven. Avonturen van een vader en zijn zoon 26 Nummer Avonturen van een vader en zijn zoon 25 Nummer Avonturen van een vader en zijn zoon 24 Nummer Avonturen van een vader en zijn zoon 23 Nummer Avonturen van een -

2019-09-12-Pk-Fbd-Final.Pdf

PRESS KIT Brussels, September 2019 The 2019 Brussels Comic Strip Festival Brussels is holding its 10th annual Comic Strip Festival from 13 to 15 September 2019 From their beginning at the turn of the previous century, Belgian comics have really become famous the world over. Many illustrators and writers from our country and its capital are well- known beyond our borders. That is reason enough to dedicate a weekend to this rich cultural heritage. Since its debut in 2010, the Brussels Comic Strip Festival has become the main event for comics fans. Young and old, novices and experts, all share a passion for the ninth art and come together each year to participate in the variety of activities on offer. More than 100,000 people and some 300 famous authors gather every year. For this 2019 edition, the essential events are definitely on the schedule: autograph sessions, the Balloon's Day Parade and many more. There's a whole range of activities to delight everyone. Besides the Parc de Bruxelles, le Brussels Comic Strip Festival takes over the prestigious setting of Brussels' Palais des Beaux-Arts, BOZAR. Two places that pair phenomenally well together for the Brussels Comic Strip Festival. Festival-goers will be able to stroll along as they please, enjoying countless activities and novelties on offer wherever they go. From hundreds of autograph signings to premiere cartoon screenings and multiple exhibitions and encounters with professionals, ninth art fans will have plenty to keep them entertained. Finally, the Brussels Comic Strip Festival will award comics prizes: The Atomium Prizes, during a gala evening when no less than €90,000 will be awarded for the best new works from the past year. -

De Stallaert Jaren

NERO DE STALLAERT JAREN 1967-19681967-1968 Nero_Integraal2_Binw.indb 1 16/10/18 16:13 De vrouwen van Sleen en Stallaert “Met de fantasie is het als met een sigaar en met een vrouw: als ze uitgaat, deugt ze niet meer!” Niemand verslikte zich in zijn koffie, toen Marc Sleen in 1962 in de Volksmacht - het blad van de christelijke vakbond - zei dat je zowel met vrouwen als met sigaren een probleem hebt als ze uitgaan. Wanneer Sleen acht jaar later, in het befaamde album ‘De dolle Dina’s’, duchtig de draak steekt met het oprukkende feminisme, krijgt hij wél kritische vragen. Vragen waarop hij, onder andere in het voor die tijd progressieve vrouwenblad Mimo, antwoordt dat voor hem de vrouw ‘liefst in bed en in de keuken’ hoort. Moeilijk te bevatten dat deze woorden uit de mond komen van de man die het feministische strippersonage pur sang creëerde: de onovertroffen Madam Pheip. – Noël Slangen en Yves Kerremans Een heel bazig, pijprokend manwijf Madam Pheip is gebaseerd op een jeugdherinnering van Sleen, uit de tijd dat hij in Sint-Niklaas woonde: “Madam Pheip, dat was de eigenares van een wassalon uit Sint-Niklaas waar ik elke dag langs moest. Ik stak de straat over als zij er was, want ik was er bang voor: een heel bazig, pijprokend manwijf dat het passerende werkvolk uitschold.1 ‘Hebben jullie nog nooit een vrouw met een pijp gezien?’ schreeuwde ze steeds.2 Volgens mij was ze niet goed snik, maar goed, een vrouw die pijp rookte en daar ook trots op was, was wellicht het gevolg van de eman- cipatie van die tijd. -

Suske En Wiske Junior - Ijs Cool Gratis

SUSKE EN WISKE JUNIOR - IJS COOL GRATIS Auteur: Willy Vandersteen Aantal pagina's: 64 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: none Uitgever: none EAN: 9789002240720 Taal: nl Link: Download hier Junior Suske en Wiske - Ijs-cool - 1e druk sc Neem je favoriete striphelden overal mee naar toe. Spike and suzy u. Suske en wiske bob and bobette or spike and suzy in the uk, willy and wanda suske en wiske comic book in america, bob and bobette in france and israel suske en wiske comic book is a long- running since flemish comic book series. The regular edition has a red linen cover. Book mint condition, cover with some scrapes on the left side on the back. The adventures of the suske en wiske comic book inseparable child heroes suske and wiske were the reason some children sneakily read well into the night with the help of a flashlight. Pdf 13 suske en wiskede sissende sampa - Discover and save! Uitgegeven in opdracht van de efteling ter gelegenheid van de 75e verjaar. The story was first written and drawn by willy vandersteen in and published in several newspapers. For this subscribers special, we will be taking a look at the suske en wiske: sony- san comic book, and this comic book is a very cool collector' s item for sony fans! Reading from left to right, they are: tante sidonia wiske' s aunt , wiske, lambik a pompous but good- hearted friend of. Hurry - limited offer. Money back guarantee! Here a tribute to a special dutch comic book suske en wiske bondage- addicted asked me for! Ontdek je strips vanaf nu op pc, tablet of smartphone! See more ideas about comic books, comic book cover, comics. -

Discord & Consensus

c Discor Global Dutch: Studies in Low Countries Culture and History onsensus Series Editor: ulrich tiedau DiscorD & Discord and Consensus in the Low Countries, 1700–2000 explores the themes D & of discord and consensus in the Low Countries in the last three centuries. consensus All countries, regions and institutions are ultimately built on a degree of consensus, on a collective commitment to a concept, belief or value system, 1700–2000 TH IN IN THE LOW COUNTRIES, 1700–2000 which is continuously rephrased and reinvented through a narrative of cohesion, and challenged by expressions of discontent and discord. The E history of the Low Countries is characterised by both a striving for consensus L and eruptions of discord, both internally and from external challenges. This OW volume studies the dynamics of this tension through various genres. Based C th on selected papers from the 10 Biennial Conference of the Association OUNTRI for Low Countries Studies at UCL, this interdisciplinary work traces the themes of discord and consensus along broad cultural, linguistic, political and historical lines. This is an expansive collection written by experts from E a range of disciplines including early-modern and contemporary history, art S, history, film, literature and translation from the Low Countries. U G EDIT E JANE FENOULHET LRICH is Professor of Dutch Studies at UCL. Her research RDI QUIST AND QUIST RDI E interests include women’s writing, literary history and disciplinary history. BY D JAN T I GERDI QUIST E is Lecturer in Dutch and Head of Department at UCL’s E DAU F Department of Dutch. -

Plankgas En Plastronneke - Het Belang Van Limburg Gratis

PLANKGAS EN PLASTRONNEKE - HET BELANG VAN LIMBURG GRATIS Auteur: Urbanus Aantal pagina's: 32 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: none Uitgever: Concentra Uitgeversmaatschappij||9789071762970 EAN: nl Taal: Link: Download hier Plankgas en Plastronneke 1 (Het Belang van Limburg) Alle artikelen. Filter resultaten. Populariteit Prijs laag - hoog Prijs hoog - laag Verschijningsdatum Beoordeling. Jef Nys Jommeke - de kimono van yamamatsu het belang van Limburg Tweedehands. Toon tweedehands. LeLoup Yoko tsuno - de hemelse jonk het belang van Limburg Tweedehands. Urbanus Plankgas en plastronneke - het belang van Limburg Tweedehands. Hec Leemans Fc de Kampioenen Tweedehands. Concentra Uitgeversmaatschappij E-encyclopedie - insecten Tweedehands. Willy Vandersteen Rode ridder, de gazet van Antwerpen Tweedehands. Hector Leemans Bakelandt - het belang van Limburg Tweedehands. Urbanus Willy Linthout Urbanus 3 Tweedehands. Mark Retera Dirkjan - het belang van Limburg Tweedehands. Raoul Cauvin Sammy - lady 'o' het belang van Limburg Tweedehands. Lady 'O' - versie Het Belang van Limburg. Jan Latinne Jan latinne Tweedehands. Greg Aertssen Aertssen - kroniek van een familiebedrijf Tweedehands. Machtige streetart op de betonnen pijlers aan Bib Park. Door Merho en de Kiekeboes geı̈nspireerd. Een mooie reportage van Striptiek op het openingsfeest voor de expo 'Merho, de Kiekeboes en Merksem' in Bibliotheek Park. Merho ging zondag zelf nog eens kijken naar zijn Kiekeboes aan Bibliotheek Park in Merksem. Bekijk hier zijn fotoreportage. Secciones de esta página. Ayuda sobre accesibilidad. Correo electrónico o teléfono Contraseña ¿Has olvidado los datos de la cuenta? Ver más de Kiekeboe - officiële fanpagina en Facebook. Ahora no. Publicaciones de visitantes. Tim De Keirsmaeker. Kurt Ureel. Información sobre los datos de las estadísticas de la página. Kiekeboe - officiële fanpagina 1 de diciembre a las ·. -

GNX Main 7X10 Frames.Vp

GRAPHIC NOVELS CORE COLLECTION FIRST EDITION CORE COLLECTION SERIES FORMERLY STANDARD CATALOG SERIES MARIA HUGGER, GENERAL EDITOR CHILDREN’S CORE COLLECTION MIDDLE & JUNIOR HIGH CORE COLLECTION SENIOR HIGH CORE COLLECTION NONFICTION CORE COLLECTION FICTION CORE COLLECTION YOUNG ADULT FICTION CORE COLLECTION GRAPHIC NOVELS CORE COLLECTION GRAPHIC NOVELS CORE COLLECTION FIRST EDITION EDITED BY KENDAL SPIRES GABRIELA TOTH AND MARIA HUGGER H. W. Wilson A Division of EBSCO Information Services Ipswich, Massachusetts 2016 GREY HOUSE PUBLISHING Copyright © 2016 by The H. W. Wilson Company, A Division of EBSCO Informa- tion Services. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner. ISBN 978-1-68217-070-0 Abridged Dewey Decimal Classification and Relative Index, Edition 15 is © 2004-2012 OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc. Used with Permission. DDC, Dewey, Dewey Deci- mal Classification, and WebDewey are registered trademarks of OCLC. Graphic Novels Core Collection, 2016, published by Grey House Publishing, Inc., Amenia, NY, under exclusive license from EBSCO Infomation Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Publisher’s Cataloging-In-Publication Data (Prepared by The Donohue Group, Inc.) Names: Spires, Kendal, editor. | Toth, Gabriela, editor. | Hugger, Maria, editor. Title: Graphic novels core collection / edited by Kendal Spires, Gabriela Toth, and Maria Hugger. Other Titles: Core collection series. Description: First edition. | Ipswich, Massachusetts : H. W. Wilson, a division of EBSCO Information Services ; Amenia, NY : Grey House Publishing, 2016. -

Suske En Wiske 274 - De Fleurige Floriade Gratis

SUSKE EN WISKE 274 - DE FLEURIGE FLORIADE GRATIS Auteur: Willy Vandersteen Aantal pagina's: 56 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: 2002-01-01 Uitgever: Standaard Uitgeverij EAN: 9789002211331 Taal: nl Link: Download hier Suske en Wiske nr 274 de fleurige floriade De eerste aflevering van deze strip stond in De Nieuwe Standaard van 30 maart De titel luidde echter De avonturen van Rikki en Wiske. Omdat Vandersteen achteraf ook niet geheel gelukkig was met de figuur Rikki liet hij deze aan het begin van het volgende verhaal verdwijnen. In dat tweede verhaal verschijnt de huidige Suske op het toneel. De ontmoeting tussen hem en Wiske zou het begin blijken te zijn van een van de langst lopende en meest populaire strip-series van Europa. Een grote bijdrage aan het succes werd ook geleverd door de verschijning van Lambik. Vandersteen heeft later wel gezegd dat veel elementen van zijn eigen karakter terug te vinden zijn in de persoon van Lambik. De vaste kern van de serie werd compleet toen de ijzersterke Jerom in het verhaal De dolle musketiers zijn opwachting maakte als geheim wapen. Nadat hij, door toedoen van Wiske en vooral Schanulleke, een vriend van de striphelden geworden was, bleef hij als vaste speler in de serie optreden. Naast de verhalen van Suske en Wiske heeft Vandersteen in deze beginperiode nog vele andere verhalen in de meest uiteenlopende genres getekend. Een serie die in dit overzicht zeker niet mag ontbreken is De familie Snoek. De belevenissen van dit gezin waren gedurende vele jaren zeer populair en vormen een goed voorbeeld van de zeer eigen humor van Vandersteen. -

De Ka-Fhaar Gratis Epub, Ebook

DE KA-FHAAR GRATIS Auteur: Merho Aantal pagina's: 48 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: 2010-10-01 Uitgever: Standaard Uitgeverij EAN: 9789002240690 Taal: nl Link: Download hier De Ka-Fhaar (De Kiekeboes 20) - stripverhaal bestellen Target audience:. Stripverhalen , Avonturenverhalen. Content Details De Ka-Fhaar, èèn van de beroemdste diamanten ter wereld, wordt gestolen door de bekende acteur Leo Sarbimko. Dankzij vele vermommingen weet Sarbimko telkenmale te ontsnappen, tot hij Kiekeboe tegen het lijf loopt. Title De ka-fhaar Author Merho. Language Dutch. Edition 1. Publisher Antwerpen: Standaard, 46 p. ISBN paperback. Technical view. Early life Robert Merhottein was born in Antwerp, Belgium in Career Merho's first two comics, Comi en Dakske and Zoz and Zef, were made when he is only a teenager. De Kiekeboes Merho. View the full list. Charlotte is lid van een wijnclub. Van der Neffe wil zijn ex-vrouw Carmella weer voor zich winnen. Hij boekt een verblijf in een resort in een klein Frans dorpje. Een plek waar koppels met relatieproblemen hun liefde herontdekken dankzij de excentrieke methodes van therapeute Camille Faux. Ondertussen belanden ook de Kiekeboes in Frankrijk, waar Fanny op zoek gaat naar haar verdwenen vriendin Alanis. Charlotte bezoekt samen met Marcel enkele wijngaarden en dan loopt het compleet fout. Down under. Down under neemt jong en oud mee achter de schermen bij de Kiekeboes- strip: de twee Australië-albums Het boemerangeffect en De kangoeroeclub worden afgewisseld met een uitgebreid verslag van auteur Merho. Hij laat zien hoe hij op zijn reis in Australië geïnspireerd werd door de locaties, de mensen en de plaatselijke bezienswaardigheden aan de hand van foto's, knipsels en anekdotes.