Conrad Tao & Beethoven's "Eroica"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phoenix Symphony Music Director Tito Muñoz to Conduct Berkeley Symphony Concert Thursday, February 4 at Zellerbach Hall

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE / February 1, 2016 Contact: Jean Shirk [email protected] / 510-332-4195 http://www.berkeleysymphony.org/about/press/ Phoenix Symphony Music Director Tito Muñoz to conduct Berkeley Symphony concert Thursday, February 4 at Zellerbach Hall Berkeley Symphony Music Director Joana Carneiro withdraws from concert for medical reasons l to r: Tito Muñoz, Conrad Tao. Photo credits: Muñoz: Dario Acosta. Tao: Brantley Gutierrez BERKELEY, CA (February 1, 2016) – Music Director Joana Carneiro has withdrawn from this week’s Berkeley Symphony concert with composer and pianist Conrad Tao for medical reasons. Phoenix Symphony Music Director Tito Muñoz will lead the Orchestra and Tao in a performance of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5, “Emperor,” on Thursday, February 4 at 8 pm at Zellerbach Hall in Berkeley. Muñoz also conducts the Orchestra in Lutosławski’s Concerto for Orchestra, an orchestral showpiece. Tickets are $15-$74 and are available at www.berkeleysymphony.org or by phone at (510) 841- 2800, ext. 1. Berkeley Symphony offers a $7 Student Rush ticket one hour prior to each performance for those with a valid student ID. Tito Muñoz is Music Director of the Phoenix Symphony, a post he began with the 2014-15 season. He has also held the posts of Music Director of the Opéra National de Lorraine and the Orchestre symphonique et lyrique de Nancy, Assistant Conductor of The Cleveland Orchestra, and Assistant Conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra and the Cincinnati Chamber Orchestra. An alumnus of the National Conducting Institute, Muñoz made his professional conducting debut in 2006 with the National Symphony Orchestra. -

27.1. at 20:00 Helsinki Music Centre We Welcome Conrad Tao Sakari

27.1. at 20:00 Helsinki Music Centre We welcome Conrad Tao Sakari Oramo conductor Conrad Tao piano Lotta Emanuelsson presenter Andrew Norman: Suspend, a fantasy for piano and orchestra 1 Béla Bartók: Divertimento for String Orchestra 1. Allegro non troppo 2. Molto adagio 3. Allegro assai Conrad Tao – “shaping the future of classical music” “Excess. I find it to be for me like the four, and performed Mozart’s A-major pia- most vividly human aspect of musical no concerto at the age of eight. He was performance,” says pianist Conrad Tao (b. nine when the family moved to New York, 1994). And “excess” really is a good word where he nowadays lives. Beginning his to describe his superb technique, his pro- piano studies in Chicago, he continued at found interpretations and his emphasis on the Juilliard School, New York, and atten- the human aspect in general. ded Yale for composition. Tao has a wide repertoire ranging from Tao has had a manager ever since Bach to the music of today. He has also he was twelve. As a youngster, he also won recognition as a composer, and one learnt the violin, and several times in who, he says, views his keyboard perfor- 2008/2009 played both the E-minor vio- mances through the eyes of a composer. lin concerto and the first piano concerto His many talents and his ability to cross by Mendelssohn at one and the same con- traditional borders have indeed made him cert, but he soon gave up the violin. a notable influencer and a model for ot- Despite having all the hallmarks of a hers. -

Conrad Tao ($50,000 Scholarship Recipient)

Davidson Fellow Laureate Conrad Tao ($50,000 Scholarship Recipient) Personal Info Conrad Tao Age: 14 New York, New York School, College and Career Plans Conrad is entering his sixth year at The Juilliard Pre-College Division and is a rising sophomore in the independent study program through the Indiana University High School of Continuing Studies. He would like to be a concert pianist and professional composer. Davidson Fellows Submission (Music) In his project, “Bridging Classical Music from the Past to the Future as Pianist and Composer,” Conrad makes classical music relevant to younger generations through performances that display a vast knowledge, deep understanding and mature interpretation of the repertoire. A composer, pianist and violinist attending The Juilliard Pre-College Division, he has been featured on NPR’s “From the Top,” performed at Carnegie Hall and has received five consecutive American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) Morton Gould Young Composer Awards. Biography “We’re not in 1700 anymore…we have computers, we have cell phones…come on, we need some new music!” (“From the Top,” October 2004) This remark captures Conrad’s belief that in order to move music forward we must embrace the music of today. He feels that since he is a young musician himself, he is uniquely situated to appreciate the well-known works from the past while understanding the interest the current generation has in music created in their lifetime. Before moving to New York City from Urbana, Illinois, Conrad was a detractor of contemporary music, feeling it was atonal and incomprehensible. Inspired by his Juilliard teachers, he began to understand the importance of novelty in the world of classical music and now routinely incorporates a new or underappreciated work in all his recitals and programming. -

Bravo! Vail 2020 / 1

Bravo! Vail 2020 / 1 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 26, 2020 NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC TO RETURN TO BRAVO! VAIL FOR 18th ANNUAL SUMMER RESIDENCY, JULY 22–29, 2020 MUSIC DIRECTOR JAAP VAN ZWEDEN To Conduct Music by MAHLER, TCHAIKOVSKY, MOZART, BEETHOVEN, STEVE REICH, and More BRAMWELL TOVEY To Conduct Evening of Stephen SONDHEIM AND BERNSTEIN Pianist BEATRICE RANA To Make New York Philharmonic Debut Other Soloists To Include Violinist GIL SHAHAM, Pianist CONRAD TAO, Vocalist KELLI O’HARA, Soprano JOÉLLE HARVEY, and Mezzo-Soprano SASHA COOKE The New York Philharmonic will return to Bravo! Vail in Colorado for the Orchestra’s 18th annual summer residency there, performing six orchestral concerts July 22–29, 2020. Jaap van Zweden will return to Vail as Philharmonic Music Director, conducting four concerts featuring works by Wagner, Barber, Tchaikovsky, Mozart, Mahler, Beethoven, and Steve Reich. Bramwell Tovey will return to Vail with the Philharmonic to lead two concerts: an evening of music by Stephen Sondheim and Bernstein, and a program of works by Tchaikovsky and Berlioz. The soloists include violinist Gil Shaham, pianists Beatrice Rana (in her Philharmonic and Bravo! Vail debuts) and Conrad Tao, vocalist Kelli O’Hara, soprano Joélle Harvey, and mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke. The New York Philharmonic has performed at Bravo! Vail each summer since 2003. Wednesday, July 22: Jaap van Zweden will conduct the opening concert of the Philharmonic’s residency, which will be followed by the Bravo! Vail Gala. The concert will feature Barber’s Knoxville: Summer of 1915 and Broadway selections, with vocalist Kelli O’Hara; Wagner’s Prelude to Act I of Die Meistersinger; and Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. -

Norton Reopens with New Performance and Lecture Series

Norton Reopens with New Performance and Lecture Series, and Revamped Art After Dark AMONG THOSE TO APPEAR: ARTISTS NICK CAVE, NINA CHANEL ABNEY, AND PAE WHITE, COMPOSER DAVID LANG, AND ART CRITIC HILTON ALS WEST PALM BEACH, FL (Oct. 22, 2018) – The February debut of the Norton Museum of Art’s much-anticipated expansion features more than new galleries, gardens, classrooms, auditorium, restaurant, and store. The Norton is also presenting an array of new programming. Among the new offerings are an Arts Leader Lecture Series, an Artist Talks series, a Sunday Speakers series, a Norton Cinema series, featuring independent and rarely screened films, and a Contemporary Dance series. A returning Live! At the Norton concert series will present musicians and composers on the leading edge of contemporary classical music. Artist Nick Cave’s Soundsuit-filled 2010 Norton exhibition, Meet Me at the Center of the Earth, was one of the Museum’s most popular in years. His return is highly anticipated. Composer David Lang, who is the recipient of both a Grammy Award (2010) and a Pulitzer Prize (2008), and was recently lauded in The New York Times for a creative work for 1,000 voices presented on Manhattan’s Highline, makes his first visit to the Museum for a performance of his work. Hilton Als, another Pulitzer Prize winner (for criticism in 2017), who is considered one of the freshest and most vibrant voices in arts writing today, also visits the Norton for the first time as part of the Arts Leader Lecture Series. And Chicago-born, New York-based artist Nina Chanel Abney is the subject of this year’s Recognition of Art by Women (RAW) exhibition, which annually showcases the work of an emerging, living women painter or sculptor. -

Letter from USC Radio

Map of Classical KUSC Coverage KUSC’s Classical Public Radio can be heard in 7 counties, from as far north as San Luis Obispo and as far south as the Mexican border. With 39,000 watts of power, Classical KUSC boasts the 10th most powerful signal in Southern California. KUSC transmits its programming from five transmitters - KUSC-91.5 fm in Los Angeles and Santa Clarita; 88.5 KPSC in Palm Springs; 91.1 KDSC in Thousand Oaks; 93.7 KDB in Santa Barbara and 99.7 in Morro Bay/San Luis Obispo. KUSC Mission To make classical music and the arts a more important part of more people’s lives. KUSC accomplishes this by presenting high quality classical music programming, and by producing and presenting programming that features the arts and culture of Southern California. KUSC supports the goal of the University of Southern California to position USC as a vibrant cultural enterprise in downtown Los Angeles. Page 1 Classical KUSC Table of Contents 1 Map of Classical KUSC Coverage / KUSC Mission 2 Classical KUSC Table of Contents 3-4 Letter from USC Radio President, Brenda Barnes 5 USC Radio Vice President / KUSC Programming Team 6 KUSC Programming On Air-Announcers 7-10 Programming Highlights 2013-14 11 KUSC Online and Tour with the Los Angeles Philharmonic 12 KUSC Interactive 13 KUSC Underwriting 14 KUSC Engineering 15 KUSC Administration 16 USC Radio Board of Councilors 17 Tours with KUSC 18 KUSC Development 19 Leadership Circle 20 Legacy Society 21 KUSC Supports the Arts 22 KUSC Revenue and Expenses Page 2 Letter From USC Radio hen I came to USC Radio almost 17 and covered the arts in the community for W years ago the Coachella Valley was decades. -

Conrad Tao, Piano Colloquially Known As the “Appassionata,” Has Back Into the Home Key of F Minor

Cal Performances Presents Program Notes Sunday, November 2, 2008, 3pm Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) except for a few very brief breaks. The music re- Hertz Hall Piano Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Op. 57, mains at a low dynamic for an extended period “Appassionata” (1804–1806) of time, making the moments of fortissimo more intense and meaningful. A faster coda brings in a Beethoven’s Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Op. 57, new theme which leads into an extended cadence Conrad Tao, piano colloquially known as the “Appassionata,” has back into the home key of F minor. The finale of long been regarded as one of the great sonatas of the “Appassionata” was unusual for Beethoven be- Beethoven’s middle period. It was begun in 1804 cause it ends on a tragic note, which seemingly had PROGRAM and completed in 1806. The “Appassionata” had a never happened before in Beethoven’s works in so- feverishly intense storminess unseen in Beethoven’s nata form. The “Appassionata” lives up to its name earlier works. In fact, the sonata was considered (which, admittedly, was not Beethoven’s at all but Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) Piano Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Op. 57, Beethoven’s most intense work until the massive that of a publisher), with fiery passion and anger “Appassionata” (1804–1806) “Hammerklavier” Sonata of 1817–1818. During present in equal measure. the composition of the “Appassionata,” Beethoven Allegro assai came to grips with his progressing deafness, and Andante con moto the music reflects on that. John Corigliano (b. -

MUSIC to HONOR a PRESIDENT NOV 3, 2013 | HOLLY BERETTO | NO COMMENT | MUSIC Texas Music Groups Commemorate 50 Th Anniversary of JFK Assassination

MUSIC TO HONOR A PRESIDENT NOV 3, 2013 | HOLLY BERETTO | NO COMMENT | MUSIC Texas Music Groups Commemorate 50 th Anniversary of JFK Assassination IMAGE ABOVE: President John F. Kennedy, May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963. Robert Simpson, artistic director of the Houston Chamber Choir, will lead the group in Requiem for a President on Nov. 9. Courtesy photo. This month across Texas, performing arts organizations are offering new works and classic favorites to commemorate the 50th anniversary of JFK assassination, and celebrate the life of the young president from Massachusetts who so captivated the country. As the Kennedys opened their doors to renowned musicians, opera singers, and conductors, it seems fitting to honor a fallen President with music. Houston Chamber Choir presentsRequiem for a President on Nov. 9, which includes Adagio for Strings, arranged for voices by Samuel Barber, A Curse on Iron, by Estonian composer Veljo Tormis, and Maurice Duruflé’s Requiem. ―President Kennedy’s death is riveted to the national psyche,‖ says Robert Simpson, artistic director of the Houston Chamber Choir. ―His death was a national moment for everyone who was alive at that time.‖ Simpson remembers that the Adagio, the second movement from Barber’s String Quartet, was playing when Kennedy’s assassination was announced on television. The other works on the program address hope and humanity. ―I wanted pieces that would reach in and touch people,‖ he says. ―The Requiem, influenced by Gregorian chant, is more uplifting than fire-and-brimstone; it’s evocative of peace. The Curse on Iron is taken from an epic Finish poem about that country’s national identity as it pulled away from Sweden. -

Classical Music

2020– 21 2020– 2020–21 Music Classical Classical Music 1 2019– 20 2019– Classical Music 21 2020– 2020–21 Welcome to our 2020–21 Contents Classical Music season. Artists in the spotlight 3 We are committed to presenting a season unexpected sounds in unexpected places across Six incredible artists you’ll want to know better that connects audiences with the greatest the Culture Mile. We will also continue to take Deep dives 9 international artists and ensembles, as part steps to address the boundaries of historic Go beneath the surface of the music in these themed of a programme that crosses genres and imbalances in music, such as shining a spotlight days and festivals boundaries to break new ground. on 400 years of female composition in The Ghosts, gold-diggers, sorcerers and lovers 19 This year we will celebrate Thomas Adès’s Future is Female. Travel to mystical worlds and new frontiers in music’s 50th birthday with orchestras including the Together with our resident and associate ultimate dramatic form: opera London Symphony Orchestra, Britten Sinfonia, orchestras and ensembles – the London Los Angeles Philharmonic, The Cleveland Symphony Orchestra, BBC Symphony Awesome orchestras 27 Orchestra and Australian Chamber Orchestra Orchestra, Britten Sinfonia, Academy of Ancient Agile chamber ensembles and powerful symphonic juggernauts and conductors including Sir Simon Rattle, Music, Los Angeles Philharmonic and Australian Choral highlights 35 Gustavo Dudamel, Franz Welser-Möst and the Chamber Orchestra – we are looking forward Epic anthems and moving songs to stir the soul birthday boy himself. Joyce DiDonato will to another year of great music, great artists and return to the Barbican in the company of the great experiences. -

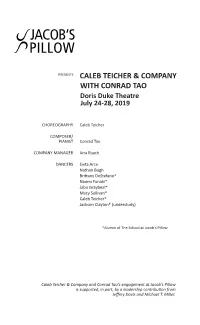

Caleb Teicher & Company with Conrad

PILLOWNOTES JACOB’S PILLOW EXTENDS SPECIAL THANKS by Brian Schaefer TO OUR VISIONARY LEADERS The PillowNotes series comprises essays commissioned from our Scholars-in-Residence to provide audiences with a broader context for viewing dance. VISIONARY LEADERS form an important foundation of support and demonstrate their passion for and commitment to Jacob’s Pillow through In March 2011, at the famed St. Mark’s Church in New York City’s East Village, a performance took place that annual gifts of $10,000 and above. would herald the arrival of several exciting new dance voices. It was called "A Shared Evening" and those sharing the evening were Dormeshia Sumbry-Edwards, a seasoned tap master whose career includes several Their deep affliliation ensures the success and longevity of the Broadway shows, and Michelle Dorrance, then a young phenom and alumna of the percussive spectacle Pillow’s annual offerings, including educational initiatives, free public STOMP. On stage, the two presented work anchored in the tap tradition but that also expanded its theatrically programs, The School, the Archives, and more. in inventive ways. Performing in Dorrance’s work was a spirited 17-year-old who gamely attacked the complex rhythms and executed the tricky choreography with an easy smile. His name was Caleb Teicher, and he would go on to earn PRESENTS $25,000+ a Bessie Award for his role in that show and become a founding member of Dorrance Dance, the influential CALEB TEICHER & COMPANY Carole* & Dan Burack Christopher Jones* & Deb McAlister tap troupe that sprung from the St. Mark’s Church performance. -

As We Tentatively Begin to Emerge from the Pandemic, What Will the Fall Orchestra Season Look Like? One Thing Is Certain: It Won’T Be Business As Usual

Seasons of Change As we tentatively begin to emerge from the pandemic, what will the fall orchestra season look like? One thing is certain: It won’t be business as usual. Orchestras have grappled with the pandemic and sought to confront racial injustice while adopting notably different approaches to the new season. Flexibility is key, given the unpredictable nature of the pandemic. By Steven Brown 44 symphony SUMMER 2021 n a simpler, long-ago time—Janu- town Symphony’s live-concert plans: Walker, and Florence Price. One example: ary 2020—the Columbus Sym- Audiences took so well to community William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Sym- phony’s trustees ratified a new concerts by a string quartet and other phony, premiered by Leopold Stokowski mission statement: “Inspiring small ensembles—some of the group’s first and the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1934, and building a strong community performances as the shutdowns eased— will be performed by the Baltimore Sym- through music is the core of everything that the orchestra is launching a chamber phony, Cincinnati Symphony, and Seattle we do.” series to keep them in the spotlight. Symphony. New attention is also going I“At first blush, it doesn’t sound earth- After long neglecting music by women to women from the past—such as Louise shattering,” Executive Director Denise and composers of color, orchestras are Farrenc, a French contemporary of Hec- Rehg says. “But that is way different from embracing them like never before. The At- tor Berlioz, and Ida Moberg, a Finnish all the mission statements we used to lanta Symphony’s 2021-22 classical series contemporary of Jean Sibelius. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Michael Dowlan PHONE: (213) 740-3233

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Michael Dowlan PHONE: (213) 740-3233 USC THORNTON SYMPHONY PERFORMS AT WALT DISNEY CONCERT HALL UNDER THE DIRECTION OF USC PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR CARL ST.CLAIR JANUARY 27, 2013 AT 2PM. Concert features soprano Angela Brown, baritone Kevin Deas and the USC Thornton Concert Choir under the direction of Cristian Grases St.Clair also takes on a newly expanded role as Artistic Leader of USC Thornton School of Music Orchestras (Los Angeles, CA) – The USC Thornton School of Music celebrates Principal Conductor Carl St.Clair’s expanded role as Artistic Leader of the Thornton School of Music Orchestras in a very special performance featuring Maestro St.Clair leading the USC Thornton Symphony on January 27, 2013 at 2PM at Walt Disney Concert Hall. Featured works are Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess Suite and Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet. The Porgy and Bess Suite features soprano Angela Brown, baritone Kevin Deas, and USC Thornton choral faculty member, Cristian Grases, who prepared the USC Thornton Concert Choir. This special program is representative of St.Clair’s newly expanded appointment as Artistic Leader of the USC Thornton School of Music Orchestras bringing first rate guest artists and inspired programs to the students, and giving them the chance to perform in one of the world’s greatest halls. St.Clair describes the concert program in his own words: ”Both Angela and Kevin deliver the roles of Bess and Porgy in such a deeply heartfelt and authentic way that I wanted our students to experience their profound musical souls, and the interpretations which rise from within them.