On the Yellow Brick Road

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wonderful Wizards Behind the Oz Wizard

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries 1997 The Wonderful Wizards Behind the Oz Wizard Susan Wolstenholme Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Wolstenholme, Susan. "The Wonderful Wizards behind the Oz Wizard," The Courier 1997: 89-104. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXXII· 1997 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXXII 1997 Ivan Mestrovic in Syracuse, 1947-1955 By David Tatham, Professor ofFine Arts 5 Syracuse University In 1947 Chancellor William P. Tolley brought the great Croatian sculptor to Syracuse University as artist-in-residence and professor ofsculpture. Tatham discusses the his torical antecedents and the significance, for Mdtrovic and the University, ofthat eight-and-a-half-year association. Declaration ofIndependence: Mary Colum as Autobiographer By Sanford Sternlicht, Professor ofEnglish 25 Syracuse University Sternlicht describes the struggles ofMary Colum, as a woman and a writer, to achieve equality in the male-dominated literary worlds ofIreland and America. A CharlesJackson Diptych ByJohn W Crowley, Professor ofEnglish 35 Syracuse University In writings about homosexuality and alcoholism, CharlesJackson, author ofThe Lost TtVeekend, seems to have drawn on an experience he had as a freshman at Syracuse University. Mter discussingJackson's troubled life, Crowley introduces Marty Mann, founder ofthe National Council on Alcoholism. Among her papers Crowley found a CharlesJackson teleplay, about an alcoholic woman, that is here published for the first time. -

The Marvellous Land of Oz ______

The Chronicles of Oz: The Marvellous Land Of Oz __________________________ A six-part audio drama by Aron Toman A Crossover Adventures Production chroniclesofoz.com 44. EPISODE TWO 15 PREVIOUSLY Recap of the previous episode. 16 EXT. CLEARING The Sawhorse runs rampant, while Tip and Jack Pumpkinhead attempt to catch it and calm it down. JACK PUMPKINHEAD Whoah! Whoah! TIP (V.O.) Taming the Sawhorse now it was alive was proving ... tricky. When Jack came to life, he was full of questions and kinda stupid, but he was fairly calm, all things considered. The Sawhorse was frightened. And a little bit insane. JACK PUMPKINHEAD Calm down horsey! TIP Whoah, horse. Easy there boy -- look out Jack, it's coming through! JACK PUMPKINHEAD Whoooah! He leaps out of the way as the horse bounds past him. TIP Come on, there's nothing to be scared of. JACK PUMPKINHEAD I'm scared! TIP Nothing for the Sawhorse to be scared of. (to Sawhorse) We're your friends we're not going to hurt -- ahhh! He jumps aside as it rushes through. 45. JACK PUMPKINHEAD At least it's knocking you over as well as me, Dad. TIP I don't understand, why won't it listen to us? JACK PUMPKINHEAD Maybe it can't listen to us? TIP Oh? Oh, of course, that's it! Jack, find me some leaves or something. (he starts rummaging in the undergrowth) Big ones, about the size of my hand. We need two. JACK PUMPKINHEAD Why? TIP (finding leaves) Here we are, perfect. Ears, Jack! The Sawhorse doesn't have ears! JACK PUMPKINHEAD That's why he isn't listening! TIP We just need to fasten these on to his head and sprinkle a little more powder on. -

To the Baum Bugle Supplement for Volumes 46-49 (2002-2005)

Index to the Baum Bugle Supplement for Volumes 46-49 (2002-2005) Adams, Ryan Author "Return to The Marvelous Land of Oz Producer In Search of Dorothy (review): One Hundred Years Later": "Answering Bell" (Music Video): 2005:49:1:32-33 2004:48:3:26-36 2002:46:1:3 Apocrypha Baum, Dr. Henry "Harry" Clay (brother Adventures in Oz (2006) (see Oz apocrypha): 2003:47:1:8-21 of LFB) Collection of Shanower's five graphic Apollo Victoria Theater Photograph: 2002:46:1:6 Oz novels.: 2005:49:2:5 Production of Wicked (September Baum, Lyman Frank Albanian Editions of Oz Books (see 2006): 2005:49:3:4 Astrological chart: 2002:46:2:15 Foreign Editions of Oz Books) "Are You a Good Ruler or a Bad Author Albright, Jane Ruler?": 2004:48:1:24-28 Aunt Jane's Nieces (IWOC Edition "Three Faces of Oz: Interviews" Arlen, Harold 2003) (review): 2003:47:3:27-30 (Robert Sabuda, "Prince of Pop- National Public Radio centennial Carodej Ze Zeme Oz (The ups"): 2002:46:1:18-24 program. Wonderful Wizard of Oz - Czech) Tribute to Fred M. Meyer: "Come Rain or Come Shine" (review): 2005:49:2:32-33 2004:48:3:16 Musical Celebration of Harold Carodejna Zeme Oz (The All Things Oz: 2002:46:2:4 Arlen: 2005:49:1:5 Marvelous Land of Oz - Czech) All Things Oz: The Wonder, Wit, and Arne Nixon Center for Study of (review): 2005:49:2:32-33 Wisdom of The Wizard of Oz Children's Literature (Fresno, CA): Charobnak Iz Oza (The Wizard of (review): 2004:48:1:29-30 2002:46:3:3 Oz - Serbian) (review): Allen, Zachary Ashanti 2005:49:2:33 Convention Report: Chesterton Actress The Complete Life and -

Kid-Friendly*” No Matter What Your Reading Level!

Advanced Readers’ List “Kid-friendly*” no matter what your reading level! *These are suggestions for people who love challenging words and a good story, and want to avoid age-inappropriate situations. Remember though, these books reflect the times when they were written, and sometimes include out-dated attitudes, expressions and even stereotypes. If you wonder, its ok to ask. If you’re bothered, its important to say so. The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein A young boy grows to manhood and old age experiencing the love and generosity of a tree which gives to him without thought of return. Also by Shel Silverstein: Where the Sidewalk Ends: The Poems and Drawings of Shel Silverstein A boy who turns into a TV set and a girl who eats a whale are only two of the characters in a collection of humorous poetry illustrated with the author's own drawings. A Light in the Attic A collection of humorous poems and drawings. Falling Up Another collection of humorous poems and drawings. A Giraffe and a Half A cumulative tale done in rhyme featuring a giraffe unto whom many kinds of funny things happen until he gradually loses them. The Missing Piece A circle has difficulty finding its missing piece but has a good time looking for it. Runny Babbit: A Billy Sook Runny Babbit speaks a topsy-turvy language along with his friends, Toe Jurtle, Skertie Gunk, Rirty Dat, Dungry Hog, and Snerry Jake. The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame Emerging from his home at Mole End one spring, Mole's whole world changes when he hooks up with the good-natured, boat-loving Water Rat, the boastful Toad of Toad Hall, the society-hating Badger who lives in the frightening Wild Wood, and countless other mostly well-meaning creatures. -

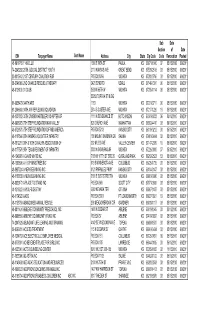

Sub Date Section of Date EIN Taxpayer Name Sort Name

Sub Date Section of Date EIN Taxpayer Name Sort Name Address City State Zip Code Code Revocation Posted 48-0916715 1149 CLUB 1006 E WEA ST PAOLA KS 66071-1840 07 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 74-2843202 20TH JUDICIAL DISTRICT YOUTH 2110 KANSAS AVE GREAT BEND KS 67530-2516 03 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 20-0815642 21ST CENTURY COALITION FOR PO BOX 8766 WICHITA KS 67208-0766 03 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 38-3746086 2ND CHANCE RESCUE & THERAPY 2420 32ND RD UDALL KS 67146-7301 00 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-6126100 31 CLUB 3539 N 55TH W WICHITA KS 67205-1114 09 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 53283 TOPEKA ST BLDG 01-0658479 344TH ARS 1183 WICHITA KS 67221-3711 00 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 91-2046668 34TH AIR REFUELING SQUADRON 2814 S CUSTER AVE WICHITA KS 67217-1226 19 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-1037882 35TH DIVISION ARTILLERY CHAPTER OF 1111 N SEVERANCE ST HUTCHINSON KS 67501-5833 06 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-0908975 7TH STEP FOUNDATION KAW VALLEY 820 CHURCH AVE MANHATTAN KS 66502-4410 03 09/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-0729370 7TH STEP FOUNDATION OF MID AMERICA PO BOX 5212 KANSAS CITY KS 66119-0212 03 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-1107546 8TH KANSAS VOLUNTEER INFANTRY 100 MOUNT BARBARA DR SALINA KS 67401-3444 03 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-1012210 9TH & 10TH CAVALRY ASSOCIATION OF 202 MILES AVE VALLEY CENTER KS 67147-2039 19 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-1177576 9TH TEXAS REGIMENT OF INFANTRY 3033 N GOVERNOUR WICHITA KS 67226-0000 07 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-1249979 A DAVIS WHITE INC 7180 W 107TH ST STE 26 OVERLAND PARK KS 66212-2523 03 05/15/2010 6/9/2011 48-1000596 A H G P MINISTRIES INC 619 S MINNESOTA AVE COLUMBUS KS -

Follow the Yellow Brick Road

CASA’s 7th Annual Red Wagon Event Follow the Yellow Brick Road There’s No Place Like Home Friday, April 7th, 2017 6:00 p.m. Fairgrounds Industrial Building There are over 300 kids each year that are appointed to CASA of There’s No Place Like Natrona County, and placed in the foster care system. Like Dorothy, when she first lands in Munchkin Land, these youth are oftentimes forced to navigate the complexities of life on their own. It only takes Home one caring person to change the course of their life for the better. Dorothy’s lucky—she found three! Together they were able to achieve their goal of finding the Emerald City and meeting the Wizard of Oz. CASA of Natrona County matches foster youth with specially trained, court appointed volunteers who provide on-going support, guid- ance and hope. CASA advocates change lives and help ensure our community’s most at-risk youth have a safe place to call home. You will hear stories, much like the Tin Woodman, Cowardly Lion and Scarecrow—from the Foster/ Adoptive Family, CASA Advocate, Guardian ad Litem and most importantly, the child. They all play an im- portant part in the success and outcome of finding a safe place to call HOME. Hear one adoption story through the perspective of everyone on the case. As there were many setbacks and delays in Dorothy’s trip to get home, there are similar delays, struggles and setbacks that can happen before a child in the foster care system is finally able to get back home. -

Follow the Yellow Brick Road

Follow the Yellow Brick Road erhaps you’ve heard that IPNI is being restructured. Key scientific resources are moving to the industry’s trade associations to strengthen their 4R and other agronomic initiatives, and to provide direct scientific support for Pengagement with their stakeholders. This transition marks the end of era. Many of us at IPNI feel like Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz as we embark on the yellow brick road in search of Emerald City. We are a little uncertain and the road ahead is not entirely straight. As seen in the movie, the road has graceful curves as it travels over the rich grassy land; it has areas where the bricks are polished and smooth and clearly marked. It also has areas where the bricks are broken or uprooted, or missing altogether like in the dark abandoned forests of Oz. The road ahead is uncertain and even frightening … change always is. But change is also exciting and reinvigorating. It causes us to adapt and to improve, and it strengthens us. IPNI has always attracted talented and highly capable scientists … scientists dedicated to improving nutrient management and nutrient use efficiency, to improving food production and farmer’s livelihoods, and to protecting our environ- ment. That dedication and service to global agriculture will not change; it will continue albeit in a different setting as our staff move on to other opportunities and challenges. IPNI is leaving a great legacy. Better Crops is part of that legacy. It’s been an honor to have worked in this amazing Institute and in partnership with all of you. -

Following the Yellow Brick Road: the Lived

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: FOLLOWING THE YELLOW BRICK ROAD: THE LIVED JOURNEY OF NURSES BECOMING NURSE PRACTITIONERS Kathleen Theresa Ogle, Doctor of Philosophy, 2007 Dissertation directed by: Professor Francine H. Hultgren Department of Education Policy and Leadership In this phenomenological study, I explore the lived experiences of registered nurses who become nurse practitioners. Text for this study comes from narrative sources such as reflective writings, one-on-one conversations, and group conversations with seven new nurse practitioners. The guiding question for this inquiry is: “What is the lived journey of nurses who become nurse practitioners?” Phenomenological philosophers such as Heidegger, Gadamer, and Casey guide this work. Other authors are drawn upon for grounding the study and to draw out the phenomenon for examination. The six research activities of van Manen (2003) provide the methodological framework for the research. The “yellow brick road” traveled by the registered nurse to nurse practitioner is the metaphor that has revealed itself as we reflect on the journey. Literature from the disciplines of nursing and education, poetry, and narrative accounts complement the stories told by nurse practitioners and open up new ways to think about the lived experience. Stories are the bricks that form the yellow road that lead us to a new way of being. Nurses who become nurse practitioners experience the journey from school to beginning practice and finally to comfort in the new place. Conversations reveal the meaning of the journey. The webs of support woven with other students are found to be very important. Before reaching the end of the road, many detours are encountered that slow, but never stop, the journey. -

Wiz Social Story

I AM GOING TO SEE: FOUR FRIENDS Dorothy This is Dorothy. She is trying to find the Wiz to send her back home to Kansas. The Scarecrow This is the Scarecrow. I am going to see The Wiz at Hope Summer Repertory Theatre. He will ask the Wiz for a brain The Wiz is a theatre show. This is different from a television show or a The Tin Man movie, because the characters are played by actors who can see and hear me, just like I can see and hear them. Once the play begins, This is the Tin Man. He will ask everyone, including me, will sit quietly so we can hear the story. the Wiz for a heart. In this show, a girl named Dorothy gets lost in the magical world of The Lion Oz, and tries to find her way back home to Kansas with the help of a Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Lion. This show is based on The Wizard of Oz. This is the Lion. He will ask the The Wiz is a kind of show called a musical. That means the actors will Wiz for some talk and sing to tell the story. Sometimes the actors will dance and courage. move quickly. At the end of the songs, people around me will clap. This might be loud. If the noise and movements make me anxious, I THREE WITCHES can use headphones or hold my friend or parent's hand. Sometimes Addaperle the characters will say or do something funny. It is ok to laugh or clap when I enjoy something. -

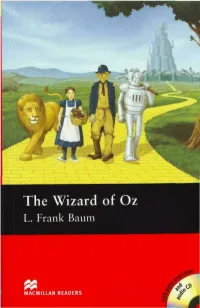

The Wizard of Oz

MACMILLAN READERS PRE-INTERMEDIATE LEVEL L. FRANK BAUM The Wizard of Oz Retold by Elizabeth Walker MACMILLAN Contents r Autho e th t abou e Not A 4 y Stor s Thi t abou e Not A 6 The People in This Story 8 1 The Cyclone 9 2 In the Land of the Munchkins 12 3 Dorothy Meets the Scarecrow 15 n Ma n Ti e th s Help y Doroth 4 19 n Lio y Cowardl e Th 5 22 6 The River 25 7 The Field of Sleep 29 8 The Queen of the Field Mice 30 9 The Emerald City 33 10 The Great Wizard of Oz 38 t Wes e th f o h Witc d Wicke e Th 1 1 43 12 In the Power of the Wicked Witch 47 13 Dorothy and the Winged Monkeys 51 14 The Wonderful Wizard of Oz 54 15 The Journey to the South 62 16 Home Again 68 Understanding for s Point 72 Glossary 76 Exercises 81 A Note Abou. tpopular Thy ver e e Authobecam s tale r y fair f o s book s hi d an s storie e thes Frank had at last found the work that he could do best. Wonderful The s wa k boo s famou t mos s Baum' k Fran . L w Ne n i , Syracuse r nea 6 185 n i n bor s wa m Bau k Fran n Lyma Wizard1 of Oz, which was published in 1900. The book made s Hi . States d Unite e th f o t par n Easter e th n i , State k Yor Frank a great deal of money. -

Follow the Yellow Brick Road: Linking Theory and Practice in Addiction Studies Teaching • College Quarterly

Follow the Yellow Brick Road: Linking Theory and Practice in Addiction Studies Teaching • College Quarterly Volume 20 • Issue 1 (2017) HOME CURRENT ISSUE EDITORIAL BOARD SUBMISSION GUIDELINES HISTORY ARCHIVES SEARCH Follow the Yellow Brick Road: Linking Theory and Practice in Addiction Studies Teaching Robin-Marie Shepherd and Tannis M. Laidlaw ROBIN-MARIE Abstract SHEPHERD This paper describes an undergraduate course in Robin-Marie Shepherd, addictions within the health science sector linking theory PhD., has been teaching with practice at a university in New Zealand. The essence and conducting research of this addiction course includes both a strong theoretical at the University of basis and public health focus. The theoretical and Auckland since 2004. She practical content is described with examples of the has moved on to private practice pursuing a students’ pedagogical journey in the course. Three clinical career in Mental conceptual elements lay at the foundation of this course Health and Addictive and are easily explained by employing the symbolic http://collegequarterly.ca/...-vol20-num01-winter/follow-the-yellow-brick-road-linking-theory-and-practice-in-addiction-studies-teaching.html[2/17/2017 6:51:02 PM] Follow the Yellow Brick Road: Linking Theory and Practice in Addiction Studies Teaching • College Quarterly Disorders. allegory found in The Wizard of Oz(Baum, 1900): that of the heart (the Tin Woodman), the brain (the Scarecrow) and courage (the Cowardly Lion). TANNIS M. LAIDLAW Tannis M. Laidlaw, PhD., Keywords: addiction course, health science, is a retired Senior undergraduates, public health approaches Lecturer in Primary Care Mental Health at the University of Auckland Introduction and former clinical This paper describes a course in addiction studies at the practitioner and now, undergraduate level in the health sciences. -

Yellow Brick Road Casino Fact Sheet for Web 2017.Indd

Owned by the Oneida Indian Nation, Yellow Brick Road Casino is a $20 million, YELLOW BRICK smoke-free, 60,000-square-foot gaming venue located in Upstate New York in the Village of Chittenango. Opened in 2015, the casino celebrates the community’s ROAD CASINO connection with the iconic story, “Th e Wonderful Wizard of Oz.” GAMING Yellow Brick Road Casino features 441 Las Vegas-style cash slot machines. Experience the fast-paced action and thrill of playing slots, with the added security of a PIN-controlled TS Rewards Card account that easily tracks your wagers, play, account balance and points earned for you. Visit Yellow Brick Road Casino for a list of available games. Table Games Enjoy 14 Table Games including: DINING • Blackjack • Craps Dorothy’s Farmhouse • 3 Card Poker Open Daily from 8am - 10pm • 4 Card Poker Counter-service restaurant serving home- • Spanish 21 style cooking • Mississippi Stud • Big 6 Wheel Wicked Good Pizza Sunday - Th ursday 11am - 10pm Keno Friday & Saturday 11am - Midnight Keno is an easy, fun game that off ers high payouts for Call (315) 366-9453 to order a small wager. You can enjoy Keno in the luxuriously Sit-down or take-out hand tossed pizza, wings, comfortable Keno lounge, while playing slots, in sandwiches and salads Wizard Hall, at one of the bars or even while you grab a bite. Play Keno and watch the winning numbers on any Heart and Courage Saloon of the digital displays located throughout the property. Monday - Saturday from 11am - 2am Sunday from Noon - 2am Country-western style bar RETAIL Winged Monkey Oz General Store Monday - Saturday from 8am – 2am Tobacco products, pre-packaged food and beverages, Sunday from Noon – 2am bingo supplies, other essentials.