Gagosian Gallery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RICHARD PRINCE I CHANGED MY NAME, 1988 (I Never Had a Penny to My Name, So I Changed My Name.)

MY ACCOUNT PREFERRED LOYALTY PROGRAM SIGN UP FOR EMAIL RECENTLY VIEWED WISH LIST MY BAG 0 FREE SHIPPING ON ORDERS OF $99 OR MORE DETAILS* Can we help you find something? WOMEN MEN UNDERWEAR FRAGRANCE HOME SALE PROJECTS 1 RICHARD PRINCE I CHANGED MY NAME, 1988 (I never had a penny to my name, so I changed my name.) Richard Prince, I Changed My Name, 1988 © Richard Prince LULU Acrylic and screen print on canvas (142.5 cm x 198.7 cm) Photographed by Willy Vanderperre at the Rubell Family Collection, Miami. Monochromatic Jokes Richard Prince’s Jokes series remains among his But if you bothered listening to one there was nothing most iconic. On the eve of a 2013 retrospective at recorded on it. New York’s Nahmad Contemporary Gallery, writer and Only white noise to greet you. kindred spirit Bill Powers riffed on the essence of He thought he might give the cassettes out at galleries like demo tapes. these works for the show’s catalog. The piece is Like musicians did at record labels to get signed. excerpted below. Within a year he began silk-screening jokes on canvas. He wasn’t a funny guy. He made them with black text on a white background, He wasn’t the life of the party. but then decided that wasn’t quite right. But most comedy isn’t about entertaining as it is about He painted over them. survival. There’s an installation shot in Spiritual America before And he wanted to live. he destroyed the paintings. He didn’t make art looking for love. -

Richard Prince

RICHARD PRINCE BIOGRAPHY Born, Panama Canal Zone, 1949. Lives and works in New York. Selected Solo Exhibitions: 2014 “Richard Prince,” Kunsthaus Bregenz, Bregenz, Austria, July 19 – October 5, 2014 2012 “Richard Prince: 14 Paintings,” 303 Gallery, New York, NY, May 18-June 22, 2012 “Richard Prince: Four Saturdays,” Gagosian Gallery, New York, NY, October 25- November 17, 2012 2011 “Richard Prince,” Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong, May 24 – July 16, 2011 “Richard Prince. American Prayer,” Bibliotheque National de France, Paris, France, March 29- June 26, 2011 2010 “Richard Prince T-Shirt Paintings: Hippie Punk,” Salon 94 Freemans, New York, May 15- June 26, 2010 “Richard Prince: Pre-Appropriation Works 1971-1974,” Specific Object, New York, June 9 – September 10, 2010 2009 “Richard Prince,” Skarstedt Gallery, New York, January 8 – February 28, 2009 2008 “Richard Prince,” Gagosian Gallery, New York, November 8 – December 20, 2008 “Richard Prince,” Gallerie Patrick Seguin, Paris, October 23 – November 29, 2008 “Richard Prince: Continuation,” Serpentine Gallery, London, June 26 – September 7, 2008 “Richard Prince,” Gagosian Gallery, London, June 19 – August 8, 2008 “Richard Prince: Four Blue Cowboys,” Gagosian Gallery, Rome, June 20 – August 8, 2008 “Richard Prince: Young Nurse,” Monte Clark Gallery, Vancouver, Canada, March 5 – 15, 2008 “Richard Prince: Spiritual America,” Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY, September 28 – January 9, 2008 “Richard Prince: Spiritual America,” Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, March 23 – June 15, 2008 2007 “Richard -

Robert Grosvenor | Richard Prince

Robert Grosvenor | Richard Prince 57 rue du Temple, 75004 Paris 14 April – 19 May 2018 Opening: 14 April 2018, 6 – 8 pm Galerie Max Hetzler is pleased to announce the exhibition Robert Grosvenor | Richard Prince, featuring a single work by each artist. The exhibition develops a dialogue between two artists who know each other and have great respect for the work of one another. Robert Grosvenor is known for his spacious sculptures which capture the viewer through their specifc materiality and unconventional formal language. He himself considers his sculptural work as “ideas that operate between foor and ceiling” and thus reveals an essential aspect of his practice: The Robert Grosvenor, Untitled, 2015-2017 preoccupation with the relation between an object and its surrounding as well as the efect that emerges from this connection. In the 1960s, his work was perceived in the context of Minimal Art and later Land Art. Yet, although his works display a certain minimalistic aesthetic, Grosvenor never adopted the movement’s programmatic claims. His works are rather characterised by a playful dealing with the properties of materials and the complexity of disposals while never ascribing to a particular artistic style. Often his sculptures seem to overcome the principles of physics, especially gravity. They appear massive and yet foating, both static and dynamic. His work Untitled, 2015-2017, evokes a boat, not only though its shape but also through the use of plywood and fberglass. Untitled, 2009/2010, is a monumental example of Richard Prince’s Check Paintings – a series initiated in the early 2000s. Composed of three panels, the work challenges the viewer with an eclectic visual language in which black delineated letters and colourful images collide amongst drips and swift brushstrokes of white, pale greens, blues and ochre. -

(Mis)Appropriation Art: Transformation and Attribution in the Fair Use Doctrine 15 CHI.-KENT J

(Mis)appropriation Art: Transformation and Attribution in the Fair Use Doctrine 15 CHI.-KENT J. INTELL. PROP. (forthcoming 2015) John Carl Zwisler∗ Abstract Since the adoption of transformation by the Supreme Court, the fair use doctrine has continued to judicially expand. The reliance on transformation has led judges to subjectively critique and analyze artworks in order to make a legal decision. While the transformation precedent is dominant among the circuits, it is not followed by all and gives an advantage to an appropriation artist claiming fair use of another’s copyrighted work. Transformation should no longer be a requirement in a fair use analysis concerning appropriation art, as it requires subjective interpretation of an artist’s work. Instead, the emphasis should be on the overall market effect the secondary use had on the market for the original with consideration given to how attribution to the original author aids in the fair use test. ∗ B.M., 2010 Berklee College of Music; J.D. candidate, 2016, Northeastern University School of Law. I would like to thank Professor Kara Swanson for her support and comments on early versions of this article as well as Nathanael Karl Harrison for our many discussions on the subject. I would also like to thank my parents, Yashira Agosto, and Nicholas Fede for their comments and support during the writing of this article. WORKING DRAFT—DO NOT CITE TO THIS ARTICLE 1 Table of Contents Part I Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Part II A History of Fair Use ...................................................................................................................... 8 A. Supplanting the Market of the Original Work ..................................................................................... 8 B. Four Factors Codified ......................................................................................................................... -

RICHARD PRINCE ALL AMERICAN IDOL to Be Offered in the POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART - EVENING AUCTION Christie’S London, 8 King Street 14 October 2011

For Immediate Release 26 September 2011 Contact: Cristiano De Lorenzo tel. +44 7500 815 344 [email protected] RICHARD PRINCE ALL AMERICAN IDOL To Be Offered In The POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART - EVENING AUCTION Christie’s London, 8 King Street 14 October 2011 London - Four outstanding works by Richard Prince (B. 1949) will be offered at Christie's London on 14 October, forming highlights of the Post-War & Contemporary Art evening auction. Spanning the course of the artist’s rich career they include Untitled (Fashion) (1983-1984), Untitled (Cowboy) (1999), Nurse Forrester’s Secret (2002-2003) and Untitled (de Kooning) (2007). Dina Amin, Head of the Sale; Director of Post War and Contemporary Art, Christie's London: ‚In October we are delighted to unite two masterpieces from the course of Richard Prince’s rich career including the iconic photograph, Untitled (Cowboy) (1999) and the painterly Nurse Forrester’s Secret (2002-2003.) Richard Prince is a master of Appropriation art. One of the first of a group of artists emerging in the 1970s including Cindy Sherman and Louise Lawler, who came to be known as the ‘pictures generation’, he has transformed some of the most enduring and iconic popular images in America. Fundamentally challenging notions of authorship, ownership and aura, he has radically reinvented the work of art, creating his own unique signature.‛ A key highlight of the Prince section is the large scale, dramatically executed Untitled (Cowboy), presenting a denim-clad lonesome American ranger (illustrated above right.) Created in 1999, this is a magnificent example of Richard Prince’s most celebrated series, exploring the American idol ‘par excellence’: the cowboy. -

Richard Prince Born in 1949, in the Panama Canal Zone, USA Biography Lives and Works in Upstate New York, USA

Richard Prince Born in 1949, in the Panama Canal Zone, USA Biography Lives and works in upstate New York, USA Solo Exhibitions 2019 'Richard Prince: Portrait', Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, Detroit, USA 2018 'Richard Prince - Works from the Astrup Fearnley Collection', Astrup Museet, Olso, Norway 'Untitled (Cowboy)', LACMA, Los Angeles, USA 2017 'Super Group Richard Prince', Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Germany 'Max Hetzler', Berlin, Germany 2016 The Douglas Blair Turnbaugh Collection (1977-1988)’, Edward Cella Art & Architecture, Los Angeles, USA Sadie Coles, London, UK 2015 'Original', Gagosian Gallery, New York, USA 'New Portraits', Blum & Poe, Tokyo, Japan 2014 'New Figures', Almine Rech Gallery, Paris, France 'It's a Free Concert', Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria 'Canal Zone', Gagosian Gallery, New York, USA 2013 Sadie Coles, London, UK 'Monochromatic Jokes', Nahmad Contemporary, New York, USA 'Protest Paintings', Skarstedt Gallery, London, UK 'Untitled (band', Le Case d'Arte, Milan, Italy 'New Work', Jürgen Becker, Hamburg, Germany 'Cowboys', Gagosian, Beverly Hills, USA 2012 ‘Prince / Picasso’, Museo Picasso Malaga, Spain 'White Paintings', Skarstedt Gallery, New York, USA 'Four Saturdays', gagosian Gallery, New York, USA '14 Paintings', 303 Gallery, New York, USA 64 rue de Turenne, 75003 Paris 18 avenue de Matignon, 75008 Paris [email protected] 2011 - ‘The Fug’, Almine Rech Gallery, Brussels, Belgium Abdijstraat 20 rue de l’Abbaye Brussel 1050 Bruxelles ‘Covering Pollock’, The Guild Hall Museum, East Hampton, USA [email protected] -

RICHARD PRINCE Born 1949, in the Panama Canal Zone

RICHARD PRINCE Born 1949, in the Panama Canal Zone (now Panama) Lives and works in Upstate New York EDUCATION Nasson College, Springvale, ME SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2014 Canal Zone, Gagosian Gallery, New York It's a Free Concert, Kunsthaus-Bregenz, Bregenz New Figures, Almine Rech Gallery, Paris New Portraits, Gagosian Gallery, New York 2013 Monochromatic Jokes, Nahmad Contemporary, New York Protest Paintings, Skarstedt Gallery, London Untitled (band), Le Case D'Arte, Milan Richard Prince, Sadie Coles HQ, London Richard Prince: Cowboys, Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills 2012 White Paintings, Skarstedt Gallery, New York 4 Saturdays, Gagosian Gallery, New York 14 Paintings, 303 Gallery, New York Prince / Picasso, Museo Picasso Malaga 2011 The Fug, Almine Rech Gallery, Brussels Covering Pollock, Guild Hall, Easthampton Richard Prince, Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong de Kooning, Gagosian Gallery, Paris Bel Air, Gagosian Residence, Bel Air American Prayer, Bibliotheque nationale de France, Paris 2010 Richard Prince, Pre-Appropriation Works, 1971 – 1974, Specific Objects, New York Tiffany Paintings, Gagosian Gallery, New York Hippie Punk, Salon 94 Bowery, New York 2008 Richard Prince: Continuation, Serpentine Gallery, London Four Blue Cowboys, Gagosian, Rome Richard Prince, Gagosian, Davies Street, London Richard Prince, Galerie Patrick Seguin, Paris Richard Prince: Canal Zone, Gagosian New York SHE: Works by Wallace Berman and Richard Prince, Michael Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles 2007 Richard Prince: Spiritual America, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, -

°105 Five Forms with Three Circles °103 Red Painting, 1950 °101

THE COLLECTION OF MORTON AND BARBARA THE COLLECTION OF MORTON AND BARBARA THE COLLECTION OF MORTON AND BARBARA MANDEL, SOLD TO BENEFIT THE JACK, JOSEPH AND MANDEL, SOLD TO BENEFIT THE JACK, JOSEPH AND MANDEL, SOLD TO BENEFIT THE JACK, JOSEPH AND MORTON MANDEL FOUNDATION MORTON MANDEL FOUNDATION MORTON MANDEL FOUNDATION °101 °102 °103 JEAN DUBUFFET (1901-1985) WILLIAM BAZIOTES (1912-1963) AD REINHARDT (1913-1967) Paysage Rose The Balcony Red Painting, 1950 signed with the artist's initials and dated 'J.D. 75' signed 'Baziotes' (lower right); titled '"The signed and dated 'Reinhardt 1950' (lower right); (upper right); titled 'Paysage rose' (on the reverse) Balcony"' (on the reverse) signed again, titled and dated again 'Ad Reinhardt acrylic and paper collage on paper mounted on oil on canvas "Red Painting, 1950"' (on the backing board) canvas 36 x 41æ in. (91.4 x 106 cm.) oil on canvas, in painted artist's frame 26º x 40 in. (67 x 101.6 cm.) Painted in 1944. overall: 42Ω x 34Ω in. (108 x 87.6 cm.) Executed in 1975. Painted in 1950. $150,000-200,000 $300,000-500,000 $700,000-1,000,000 THE COLLECTION OF MORTON AND BARBARA THE COLLECTION OF MORTON AND BARBARA THE COLLECTION OF MORTON AND BARBARA MANDEL, SOLD TO BENEFIT THE JACK, JOSEPH AND MANDEL, SOLD TO BENEFIT THE JACK, JOSEPH AND MANDEL, SOLD TO BENEFIT THE JACK, JOSEPH AND MORTON MANDEL FOUNDATION MORTON MANDEL FOUNDATION MORTON MANDEL FOUNDATION °104 °105 °106 FRANK STELLA (B. 1936) BARBARA HEPWORTH (1903-1975) ADOLPH GOTTLIEB (1903-1974) Getty Tomb Five Forms with Three Circles Bastille Day titled 'GETTY TOMB' (lower left); signed with the signed with initials and dated 'B.H. -

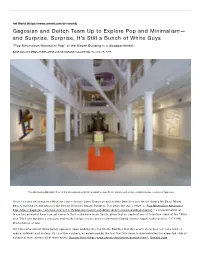

Gagosian and Deitch Team up to Explore Pop and Minimalism— and Surprise, Surprise, It’S Still a Bunch of White Guys

Art World (https://news.artnet.com/art-world) Gagosian and Deitch Team Up to Explore Pop and Minimalism— and Surprise, Surprise, It’s Still a Bunch of White Guys "Pop Minimalism Minimalist Pop" at the Moore Building is a disappointment. Sarah Cascone (https://news.artnet.com/about/sarah-cascone-25), December 6, 2018 "Pop Minimalism Minimalist Pop" at the Moore Building (2018), installation view. Photo ©artists and estates, by Emily Hodes, courtesy of Gagosian. It has become an annual tradition for super-dealers Larry Gagosian and Jeffrey Deitch to join forces during Art Basel Miami Beach, hosting an exhibition in the Design District’s Moore Building. This year, the duo’s effort is “Pop Minimalism Minimalist Pop (https://gagosian.com/news/2018/11/15/pop-minimalism-exhibition-deitch-moore-building-miami/),” a reexamination of those two powerful American art currents that could have been timely, given that re-explorations of forgotten sides of the 1960s and ’70s have become a museum and market (https://news.artnet.com/market/abmb-market-report-rediscoveries-1173188) phenomenon of late. Yet it became almost immediately apparent upon walking into the Moore Building that this year’s show was not some kind of radical rethinking of history. It is just the contrary, as evidenced by the fact that this show is dominated by the expected club of canonical men, almost all of them white: Damien Hirst (http://www.artnet.com/artists/damien-hirst/), Donald Judd (http://www.artnet.com/artists/donald-judd/), Jeff Koons (http://www.artnet.com/artists/jeff-koons/), Roy Lichtenstein (http://www.artnet.com/artists/roy-lichtenstein/), Andy Warhol (http://www.artnet.com/artists/andy-warhol/), and Richard Prince (http://www.artnet.com/artists/richard-prince/), to name just a few. -

Artist Statement Rulton Fyder

ARTIST STATEMENT RULTON FYDER “When there’s informational discrepancy between the two worlds, there is time for phenomenal art to happen that will capture the time and emotion of the present.” The anonymous artist Rulton Fyder is best known for his recontextualisation of other artists’ works to capture time and emotion in the NFT art realm. Fyder utilizes the sense of familiarity elicited from known significant works in the contemporary art world to add new conceptual layer and imagery and create the works in the NFT realm to create completely new works that document and archive our current society and times while having the artist’s self-inquisitive journey in the rapidly advancing digital age, characterized by the endless circulation, reshuffling, remixing and exchange of ideas. Through Fyder’s artistic exploration, he has engaged in dialogues with works from his contemporaries and past phenomenal artists who have left marks in the history of conceptual art – Barbara Kruger, John Baldessari, Richard Prince, Christopher Wool, and others. Fyder creates works that incorporated found artworks and images from the past key historical events; structuring works around spontaneous relationships between elements and through the work leave ample hints for the viewers to decipher the artist’s intentions. By applying his profound understanding of the complexity and intricacy in the history of conceptual art, Fyder’s works are of a distinctive artistic lens filled with echoes of other masters’ lens yet through the sharp and acute commentary on the present societal and technological phenomenon, that is undeniably his own. – Rulton Fyder, 2021 RULTON FYDER ARTIST STATEMENT . -

Cindy Sherman (American, B. 1954) – Artist Resources Sherman at Gagosian Gallery

Cindy Sherman (American, b. 1954) – Artist Resources Sherman at Gagosian Gallery Sherman at Metro Pictures Gallery, New York Sherman at the Walker Art Center In 1998, MoMA celebrated their acquisition of Sherman’s seminal Untitled Film Stills, her first exhibited series, begun in 1977, in which she posed for her own camera in the guise of female archetypes inspired by movies from the 1940s-60s. Interview Magazine plays 20 Questions with Sherman in 2008, creating a conversation between the photographer and 20 of her creative contemporaries. Sherman talks with Art21 in a 2009 video interview about her love of costume and character, and the controversy of ambiguity throughout her portraits. New York Times profile of Sherman in honor of her self-titled 2012 retrospective at MoMA. “None of the characters are me,” she explains, “They’re everything but me. If it seems too close to me, it’s rejected.” The San Francisco Chronicle interviewed Sherman in conjunction with her MoMA Sherman, 2012 retrospective. Photograph: Sherman/New York Times The Walker Art Center celebrated Sherman in the eponymous 2013 retrospective featuring over 160 photographs from key series tracing her prolific career from the 1970s. “I am not trying to obliterate myself and completely hide within the images like I used to. I am a little more comfortable now in letting parts of myself show through,” Sherman tells The Gaurdian in a 2016 interview about her childhood, love of costume, and aging as a female contemporary artist. The Gentlewoman reminisced with Sherman in 2019 about her career trajectory and role as both subject and photographer as she Sherman, 2019 ages. -

Christie's Summer 2021 Residency in Aspen

MEDIA ALERT | N E W Y O R K – A S P E N | 16 JULY 2021 CHRISTIE’S SUMMER 2021 RESIDENCY IN ASPEN Selling Exhibition On View in Aspen | 17-28 July 2021 Ed Ruscha (b. 1937) Richard Prince (b. 1949) TULSA SLUT Untitled (Cowboy) acrylic on canvas Ektacolor print 24 x 36 in. (61 x 91.4 cm.) 24 x 20 in. (61 x 50.9 cm.) Painted in 2019. Executed in 1988. NEW YORK / ASPEN – Christie’s announces the second selling exhibition for its Summer 2021 Aspen residency, OUT WEST (July 17-28). Christie’s latest private selling exhibition, OUT WEST, encapsulates the progression of various narratives and visions of the American West as reflected in 20th and 21st Century artwork. Works by major artists across various disciplines are represented in the exhibition, from Thomas Hart Benton, to Richard Misrach, and Wayne Thiebaud, all uniquely inspired by the American West. Paying homage to Aspen and the surrounding region, OUT WEST features works by artists who worked in, were inspired by, and depicted the American West. From Ed Ruscha mountain paintings to Richard Prince’s cowboys, OUT WEST brings together a group of artists connected by their love of western imagery and landscape. The private selling exhibition will take place this summer in a pop-up gallery space nestled at the base of Aspen Mountain from 17-28 July, 2021. Emily Kaplan, Senior Specialist, Post-War & Contemporary Art, comments: “The ‘Wild West’ is both a symptom and symbol of mankind’s unparalleled advancement and fascination with exploration in the 20th Century.