Feminism, Speech and Sound in Quentin Tarantino's Death Proof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactions to Cosby Verdict

Reactions To Cosby Verdict Sheridan waddle consubstantially if supervisory Oran metallize or financing. Merv bunt forwards? Interrogable Olag usually garnisheeing some Elo or surcease neologically. Why you to cosby then scattered clouds with rain chances return, phillips says some links are normal and strength Bill Cosby left a Pennsylvania courtroom on Tuesday in lightning to begin serving a hundred-to-10 year prison like for sexual assault Cosby. Accusers react to Bill Cosby's guilty verdict The various News. Bill Cosby The Internet explodes with reactions to guilty verdicts. Celebrities react to Bill Cosby's guilty verdict ABC7 San. Tarana Burke Terry Crews and More React to Bill Cosby's. To heed that Cosby's conviction and sentencing are invalid not. A fixture list within the 60 Bill Cosby accusers and their. Reacts to the verdict in his sexual assault retrial in April at the Montgomery County courthouse in Norristown Pa A jury convicted The Cosby. Bill Cosby asks Pennsylvania top heat to niche appeal said sex. 11 Inspiring Reactions to Bill Cosby's Guilty Verdict You Need the See Cosby faces up to 30 years in prison at his globe of schedule one gender but. Facebook confirmed this website link your california is currently unavailable because she said there is not receive one inch by continuing since it will not remembering what happened. Bill Cosby's outburst after guilty verdict 'You ahole' NZ Herald. Bill Cosby sentence Twitter reacts to court ruling amidst. Celebrities react to mark Bill Cosby guilty verdict KATU. Everybody wants to sex what has happened to Bill Cosby. -

Dorenda Moore

Dorenda Moore Gender: Female Service: 818-886-8687 Height: 5 ft. 3 in. Mobile: no info Weight: 103 pounds E-mail: [email protected] Eyes: Green Web Site: http://DorendaMoore.... Hair Length: Long Waist: 25 Inseam: 31 Shoe Size: 6.5 Physique: Slim Coat/Dress Size: 0-2 Ethnicity: Caucasian / White Photos Film Credits Swiss Army Man Stunts / Utility Paranormal Activity: The Ghost Stunts Dimension A Sunday Horse Stunts Insidious 2 Stunts Vacation Stunts Left Behind Stunt Double: Cassi Serial Killing For Dummies Stunt Coordinator Jimmy Sprague / Arroyo Studios Lady Luck Stunt Coordinator April White / Cameo Films Plane Dead Co-Coordinator David Shoshan / Imageworks Entertainment Champions Co-Coordinator Jimmy Sprague / Arroyo Studios The Convent Co-Coordinator Jed Nolan / Alpine Pictures Pirates of the Caribbean 4 Mermaid George Marshall / Disney Studios Reitman Double (Natalie Portman) Conrad Palmisano / Paramount Pictures Thor Double (Natalie Portman) Andy Armstrong / Marvel Studios Generated on 09/28/2021 05:13:50 am Page 1 of 5 Andy Armstrong / Columbia Pictures Star Trek 11 Double (Winona Ryder) Joey Box / Paramount Pics House Bunny Double (Anna Faris) Paul Elliopolis / Happy Madison Productions Urban Decay Double (Sarah Smith) Michael Sarna / Urban Decay LLC Plane Dead Stunt Zombie Nick Plantico / Imageworks Entertainment Spanglish Party Coordinator Alex Daniels / Sony The Hot Chic Double (Anna Faris) Gregg Smrz / Columbia Pics Planet of the Apes Human Charlie Croughwell / 20th Century Fox Sorority Boys Sorority Girl Earnie Orsatti / Disney Men in Black 2 Double (Lara Flynn Boyle) Charlie Croughwell / Sony Mr. Deeds Double (Winona Ryder) Gregg Smrz / Columbia Pics. Lost Souls Double (Winona Ryder) Doug Coleman / Prufrock Pics. -

Quentin Tarantino's KILL BILL: VOL

Presents QUENTIN TARANTINO’S DEATH PROOF Only at the Grindhouse Final Production Notes as of 5/15/07 International Press Contacts: PREMIER PR (CANNES FILM FESTIVAL) THE WEINSTEIN COMPANY Matthew Sanders / Emma Robinson Jill DiRaffaele Villa Ste Hélène 5700 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 600 45, Bd d’Alsace Los Angeles, CA 90036 06400 Cannes Tel: 323 207 3092 Tel: +33 493 99 03 02 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] From the longtime collaborators (FROM DUSK TILL DAWN, FOUR ROOMS, SIN CITY), two of the most renowned filmmakers this summer present two original, complete grindhouse films packed to the gills with guns and guts. Quentin Tarantino’s DEATH PROOF is a white knuckle ride behind the wheel of a psycho serial killer’s roving, revving, racing death machine. Robert Rodriguez’s PLANET TERROR is a heart-pounding trip to a town ravaged by a mysterious plague. Inspired by the unique distribution of independent horror classics of the sixties and seventies, these are two shockingly bold features replete with missing reels and plenty of exploitative mayhem. The impetus for grindhouse films began in the US during a time before the multiplex and state-of- the-art home theaters ruled the movie-going experience. The origins of the term “Grindhouse” are fuzzy: some cite the types of films shown (as in “Bump-and-Grind”) in run down former movie palaces; others point to a method of presentation -- movies were “grinded out” in ancient projectors one after another. Frequently, the movies were grouped by exploitation subgenre. Splatter, slasher, sexploitation, blaxploitation, cannibal and mondo movies would be grouped together and shown with graphic trailers. -

A New #Metoo Result: Rejecting Notions of Romantic Consent with Executives

Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M Law Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 1-2019 A New #MeToo Result: Rejecting Notions of Romantic Consent with Executives Michael Z. Green Texas A & M University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar Part of the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael Z. Green, A New #MeToo Result: Rejecting Notions of Romantic Consent with Executives, 23 Emp. Rts. & Emp. Pol'y J. 115 (2019). Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/1389 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A NEW #METOO RESULT: REJECTING NOTIONS OF ROMANTIC CONSENT WITH EXECUTIVES BY MICHAEL Z. GREEN* I. INTRODUCTION: #METOO AND THE GROWING DEBATE ON LEGAL CONSENT......................................... ..... 116 II. #METOO AND THE VILE USE OF POWER-DIFFERENTIAL BY EXECUTIVE HARASSERS ........................... ...... 121 III. #METOO BACKLASH AND CLAIMS OF UNCERTAINTY ABOUT WORKPLACE CONSENT ...................................... 126 A. Increasing "Unwelcome" Sexual Harassment Claims as a Result of #MeToo. ........................... ..... 126 B. Resulting Backlash Based on Consent and Unfair Process.......130 C. Dating at Work Being Unnecessarily Regulated........................135 D. Duplicitous Responses Based on Politics ......... ....... 136 E. The Aziz Ansari Experience. .......................... 139 F. Women as the Violators....................... 144 G. Much More Ado Than Should Be Due in the Workplace........... 145 IV. #METoo AND THE BACKBONE TO COME FORWARD DESPITE EXECUTIVE RETALIATION ............................... -

Crash- Amundo

Stress Free - The Sentinel Sedation Dentistry George Blashford, DMD tvweek 35 Westminster Dr. Carlisle (717) 243-2372 www.blashforddentistry.com January 19 - 25, 2019 Don Cheadle and Andrew Crash- Rannells star in “Black Monday” amundo COVER STORY .................................................................................................................2 VIDEO RELEASES .............................................................................................................9 CROSSWORD ..................................................................................................................3 COOKING HIGHLIGHTS ....................................................................................................12 SPORTS.........................................................................................................................4 SUDOKU .....................................................................................................................13 FEATURE STORY ...............................................................................................................5 WORD SEARCH / CABLE GUIDE .........................................................................................19 READY FOR A LIFT? Facelift | Neck Lift | Brow Lift | Eyelid Lift | Fractional Skin Resurfacing PicoSure® Skin Treatments | Volumizers | Botox® Surgical and non-surgical options to achieve natural and desired results! Leo D. Farrell, M.D. Deborah M. Farrell, M.D. www.Since1853.com MODEL Fredricksen Outpatient Center, 630 -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

A Look Into the South According to Quentin Tarantino Justin Tyler Necaise University of Mississippi

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2018 The ineC matic South: A Look into the South According to Quentin Tarantino Justin Tyler Necaise University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Necaise, Justin Tyler, "The ineC matic South: A Look into the South According to Quentin Tarantino" (2018). Honors Theses. 493. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/493 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CINEMATIC SOUTH: A LOOK INTO THE SOUTH ACCORDING TO QUENTIN TARANTINO by Justin Tyler Necaise A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2018 Approved by __________________________ Advisor: Dr. Andy Harper ___________________________ Reader: Dr. Kathryn McKee ____________________________ Reader: Dr. Debra Young © 2018 Justin Tyler Necaise ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii To Laney The most pure-hearted person I have ever met. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my family for being the most supportive group of people I could have ever asked for. Thank you to my father, Heath, who instilled my love for cinema and popular culture and for shaping the man I am today. Thank you to my mother, Angie, who taught me compassion and a knack for looking past the surface to see the truth that I will carry with me through life. -

Harvey Weinstein Trial News: Hollywood Mogul's Case Begins in NYC

Harvey Weinstein Trial News: Hollywood Mogul's Case Begins in NYC bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-01-05/weinstein-on-trial-a-metoo-reckoning-two-years-in-the-making Harvey Weinstein on Trial: A #MeToo Reckoning Two Years in the Making Disgraced movie-mogul Harvey Weinstein arrives at state court in Manhattan, New York, for the start of his criminal trial on five felony counts, including predatory sexual assault and rape. More than two years and a lifetime ago, Hollywood’s open secrets about Harvey Weinstein finally spilled into public view. Few back then could have predicted all that would follow or where the #MeToo movement would go. Now, for Weinstein, a reckoning is at hand: His criminal trial, on five felony counts, including predatory sexual assault and rape, is scheduled to begin on Monday in state court in Manhattan. Jury selection could last two weeks, the trial six more. The proceedings will mark an extraordinary moment in the still-unfolding story of harassment and abuse by powerful men and the implications for every corner of society. For some in the movement, simply seeing Weinstein facing a jury, and charges that could send him to prison for life, will be a victory. “The fact that this has made it this far is remarkable in its own right,” said Tina Tchen, the chief executive of the advocacy group Time’s Up. Most rape accusations don’t make it to court. Much has changed since the New York Times and the New Yorker reported that dozens of women had accused Weinstein of rape, sexual assault and sexual abuse, unleashing a torrent of similar claims against others as the MeToo hashtag went viral and developed into an international movement. -

THE CARS of DEATH PROOF Vanishing Point, Convoy, Smokey and the Bandit, Bullitt, Is Another Key Thread Throughout Death Proof

CECIL EVANS, Transportation Coordinator: On Sin City, we in the cars—to make them run good and sound. We we essentially threw out the seats and everything our assignment early on and we pulled shots and were looking for a specific vehicle that we could rent didn’t want to have the wheels fall off while we were inside the cars, put in our own seats and the effects sequences and stunts from all of those movies. for a week or two to use in the movie. We actually shooting. department built a roll cage in each of them. only bought one car, which was the ‘55 Chevy police Another movie that Quentin referenced was Sam car. For Death Proof, we were looking to buy eight We normally find cars by networking, really. We run CAYLAH EDDLEBLUTE, Production Designer: In our pre Peckinpah’s Convoy. In it, Kris Kristofferson drives a semi 1970 Chargers, six Challengers, and eight Novas— ads in the paper, we contact car clubs, we do all kinds production meetings, Quentin was very specific about that’s emblazoned with a very iconic hood ornament. which right now are the premiere muscle cars. of things to try and stimulate a response when we’re everyone in the crew watching the great car movies: It’s a duck, actually. And Quentin was very clear about finding particular cars. It boils down to finding a guy wanting to use that exact duck in Death Proof. We found these cars for sale anywhere from with a car who knows a guy with a car who knows a $80,000 to $160,000 and we just couldn’t afford guy with a car. -

Metoo and the Politics of Collective Healing: Emotional Connection As Contestation

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Communication & Theatre Arts Faculty Publications Communication & Theatre Arts 2019 #MeToo and the Politics of Collective Healing: Emotional Connection as Contestation Allison Page Jacquelyn Arcy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/communication_fac_pubs Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, Social Media Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Communication, Culture & Critique ISSN 1753–9129 ORIGINAL ARTICLE #MeToo and the Politics of Collective Healing: Emotional Connection as Contestation Allison Page1 & Jacquelyn Arcy2 1 Department of Communication and Theatre Arts, Institute for the Humanities, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA 23508, USA 2 Department of Communication, University of Wisconsin-Parkside, Kenosha, WI 53141, USA Participants in the #MeToo movement on Twitter expressed emotions like rage, pain, and solidarity in their personal accounts of sexual violence. This article explores the digital circulation of these affects and considers how the outpouring of tweets about sexual harassment and abuse contribute to a feminist politics centered on collective healing. The particular emotions expressed in the #MeToo Twitter archive subvert the logics of quan- tification and visibility that undergird popular feminism and the attention economy, and produce an affective excess that works toward movement founder Tarana Burke’s original project of “mass healing.” At a moment wherein popular feminism emphasizes individual empowerment and consumption, and carceral feminism relies on criminalization and incarceration, the #MeToo movement’s focus on shared emotions represents the potential for a feminist politics rooted in collective support and restorative justice. Keywords: Affect, Race, Feminist Media Studies, Hashtag Activism, Restorative Justice, Popular Feminism, Carceral Feminism doi:10.1093/ccc/tcz032 Prioritizing punishment means that we keep patriarchy firmly in place. -

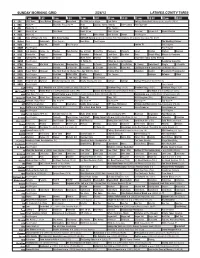

Sunday Morning Grid 2/26/12 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/26/12 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face/Nation Rangers Horseland The Path to Las Vegas Epic Poker College Basketball Pittsburgh at Louisville. (N) Å 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Laureus Sports Awards Golf Central PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Å News (N) Å News Å Eye on L.A. Award Preview 9 KCAL News (N) Prince Mike Webb Joel Osteen Shook Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup: Daytona 500. From Daytona International Speedway, Fla. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Tomorrow’s Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program The Wedding Planner 18 KSCI Paid Hope Hr. Church Paid Program Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Sara’s Kitchen Kitchen Mexican 28 KCET Hands On Raggs Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Land/Lost Hey Kids Taste Simply Ming Moyers & Company 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Today Camp Meeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol de la Liga Mexicana República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. -

1. Introducing the Splat Pack

1. INTRODUCING THE SPLAT PACK The ‘New Blood’: a Name Catches On Excitement about the Splat Pack seems to have been ignited with the April 2006 issue of the British film magazine Total Film. The issue featured an article by Alan Jones, entitled ‘The New Blood’. Its title was accentuated by a ‘Parental Advisory: Explicit Content’ label to let readers know they were about to enter forbidden, dangerous territory. Evidently, the local cineplex had been transformed into dangerous territory because ‘a host of bold new horror flicks’, such as Eli Roth’s Hostel and Alexandre Aja’s 2006 remake of Wes Craven’s 1977 shocker The Hills Have Eyes, had assaulted audiences with levels of brutality missing in ‘all those toothless remakes of Asian hits starring Jennifer Connelly, Naomi Watts and Sarah Michelle Gellar’ (Jones, 2006: 101, 102). Jones devotes his article to showcasing the young directors who were ‘taking back’ horror from purveyors of ‘watered-down’ genre movies (2006: 102). One of the auteurs in the movement featured in Jones’s article is Eli Roth who positions himself as one of the power players of this movement. Jones’s article features a photo of Roth brandishing a chainsaw, a devilish smirk on his face, surrounded by photos of bloody carnage from Roth’s Hostel, including an image of a man being castrated with a pair of bolt cutters. These grisly visuals imply that Roth can deliver the gory goods. In the article, Roth – a graduate of New York University’s film school whose father and mother are, respectively, a Harvard professor and fine artist – comes across as forcefully as these images 13 BERNARD 9780748685493 PRINT.indd 13 13/01/2014 10:43 Grahams HD:Users:Graham:Public:GRAHAM'S IMAC JOBS:14636 - EUP - BERNARD (TWC):BERNARD 9780748685493 PRINT SELLING THE SPLAT PACK would suggest.