Rapid Ecological Assessment for Perrot State Park, Merrick State Park & Whitman Dam Wildlife Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wisconsin Great River Road, Thank You for Choosing to Visit Us and Please Return Again and Again

Great River Road Wisc nsin Travel & Visitors Guide Spectacular State Bring the Sights Parks Bike! 7 22 45 Wisconsin’s National Scenic Byway on the Mississippi River Learn more at wigrr.com THE FRESHEST. THE SQUEAKIEST. SQUEAk SQUEAk SQUEAk Come visit the Cheese Curd Capital and home to Ellsworth Premium Cheeses and the Antonella Collection. Shop over 200 kinds of Wisconsin Cheese, enjoy our premium real dairy ice cream, and our deep-fried cheese curd food trailers open Thursdays-Sundays all summer long. WOR TWO RETAIL LOCATIONS! MENOMONIE LOCATION LS TH L OPEN 7 DAYS A WEEK - 8AM - 6PM OPENING FALL 2021! E TM EST. 1910 www.EllsworthCheese.com C 232 North Wallace 1858 Highway 63 O Y O R P E Ellsworth, WI Comstock, WI E R A M AT I V E C R E Welcome to Wisconsin’s All American Great River Road! dventures are awaiting you on your 250 miles of gorgeous Avistas, beaches, forests, parks, historic sites, attractions and exciting “explores.” This Travel & Visitor Guide is your trip guide to create itineraries for the most unique, one-of-a-kind experiences you can ever imagine. What is your “bliss”? What are you searching for? Peace, adventure, food & beverage destinations, connections with nature … or are your ideas and goals to take it as it comes? This is your slice of life and where you will find more than you ever dreamed is here just waiting for you, your family, friends and pets. Make memories that you will treasure forever—right here. The Wisconsin All American Great River Road curves along the Mississippi River and bluff lands through 33 amazing, historic communities in the 8 counties of this National Scenic Byway. -

Official List of Wisconsin's State Historic Markers

Official List of Wisconsin’s State Historical Markers Last Revised June, 2019 The Wisconsin State Historical Markers program is administered by Local History-Field Services section of the Office of Programs and Outreach. If you find a marker that has been moved, is missing or damaged, contact Janet Seymour at [email protected] Please provide the title of the marker and its current location. Each listing below includes the official marker number, the marker’s official name and location, and a map index code that corresponds to Wisconsin’s Official State Highway Map. You may download or request this year’s Official State Highway Map from the Travel W isconsin website. Markers are generally listed chronologically by the date erected. The marker numbers below jump in order, since in some cases markers have been removed for a variety of reason. For instance over time the wording of some markers has become outdated, in others historic properties being described have been moved or demolished. Number Name and Location Map Index 1. Peshtigo Fire Cemetery ................................................................................................................................5-I Peshtigo Cemetery, Oconto Ave, Peshtigo, Marinette County 2. Jefferson Prairie Settlement ........................................................................................................................11-G WI-140, 4 miles south of Clinton, Rock County 5. Shake Rag.................................................................................................................................................................10-E -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Wis. Agency Abbreviations

GUIDE TO WISCONSIN STATE AGENCIES AND THEIR CALL NUMBERS Wisconsin Historical Society Library 816 State Street, Madison, Wisconsin 53706 Rev. to Oct. 2017 The Wisconsin State publications collection is arranged by agencies. A system of classification based on the federal Superintendent of Documents scheme was devised so that all of an agency's publications would be shelved together. This guide was produced to help you find an agency's publications. It also provides a history of agency changes in Wisconsin State government. This guide traces Wisconsin state agencies from the beginning of statehood to the present. The guide is divided into four sections. Part I is arranged alphabetically by the keyword of the agency (second column) and part II is alphabetical by call number (first column). The complete call number is not given, only the beginning alphabetical portion of the call number. Part III is a listing of subagencies with different call numbers than their parent agency. If you know the name of an agency look in Part I to find the call number In most cases everything from an agency is shelved under the call number of the major agency. There are exceptions to this. When an agency started out independently, but later became part of another agency it will still be found under its original call number. This is where Part III will prove useful. This alphabetical listing of major agencies, both past and present, with subagencies which have a different keyword classification is a reflection of an agency's history. One must remember that divisions of subagencies will have the same call number as the subagency. -

2009 STATE PARKS GUIDE.Qxd

VISITOR INFORMATION GUIDE FOR STATE PARKS, FORESTS, RECREATION AREAS & TRAILS Welcome to the Wisconsin State Park System! As Governor, I am proud to welcome you to enjoy one of Wisconsin’s most cherished resources – our state parks. Wisconsin is blessed with a wealth of great natural beauty. It is a legacy we hold dear, and a call for stewardship we take very seriously. WelcomeWelcome In caring for this land, we follow in the footsteps of some of nation’s greatest environmentalists; leaders like Aldo Leopold and Gaylord Nelson – original thinkers with a unique connection to this very special place. For more than a century, the Wisconsin State Park System has preserved our state’s natural treasures. We have balanced public access with resource conservation and created a state park system that today stands as one of the finest in the nation. We’re proud of our state parks and trails, and the many possibilities they offer families who want to camp, hike, swim or simply relax in Wisconsin’s great outdoors. Each year more than 14 million people visit one of our state park properties. With 99 locations statewide, fun and inspiration are always close at hand. I invite you to enjoy our great parks – and join us in caring for the land. Sincerely, Jim Doyle Governor Front cover photo: Devil’s Lake State Park, by RJ & Linda Miller. Inside spread photo: Governor Dodge State Park, by RJ & Linda Miller. 3 Fees, Reservations & General Information Campers on first-come, first-served sites must Interpretive Programs Admission Stickers occupy the site the first night and any Many Wisconsin state parks have nature centers A vehicle admission sticker is required on consecutive nights for which they have with exhibits on the natural and cultural history all motor vehicles stopping in state park registered. -

Guide to Promoting Bicycling on Federal Lands

GUIDE TO PROMOTING BICYCLING ON FEDERAL LANDS Publication No. FHWA-CFL/TD-08-007 September 2008 Central Federal Lands Highway Division 12300 West Dakota Avenue Lakewood, CO 80228 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA-CFL/TD-08-007 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date September 2008 Guide to Promoting Bicycling on Federal Lands 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Rebecca Gleason, P.E. 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Western Transportation Institute P.O. Box 174250 11. Contract or Grant No. Bozeman, MT 59717-4250 DTFH68-06-X-00029 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Federal Highway Administration Final Report Central Federal Lands Highway Division August 2006 – August 2008 12300 W. Dakota Avenue, Suite 210 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Lakewood, CO 80228 HFTS-16.4 15. Supplementary Notes COTR: Susan Law – FHWA CFLHD. Advisory Panel Members: Andy Clarke – League of American Bicyclists, Andy Rasmussen – FHWA WFLHD, Ann Do – FHWA TFHRC, Chris Sporl – USFS, Christine Black and Roger Surdahl – FHWA CFLHD, Franz Gimmler – Rails to Trails Conservancy, Gabe Rousseau – FHWA HQ, Gay Page – NPS, Jack Placchi – BLM, Jeff Olson – Alta Planning and Design, Jenn Dice – International Mountain Bicycling Association, John Weyhrich – Adventure Cycling Association, Nathan Caldwell – FWS, Tamara Redmon – FHWA HQ, Tim Young – Friends of Pathways. This project was funded under the FHWA Federal Lands Highway Coordinated Technology Implementation Program (CTIP). 16. Abstract Federal lands, including units of the National Park Service, National Forests, National Wildlife Refuges, and Bureau of Land Management lands are at a critical juncture. -

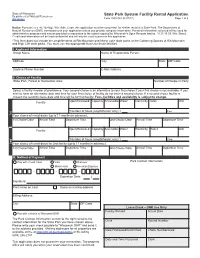

State Park System Facility Rental Application Department of Natural Resources Dnr.Wi.Gov Form 2500-042 (R 07/17) Page 1 of 6

State of Wisconsin State Park System Facility Rental Application Department of Natural Resources dnr.wi.gov Form 2500-042 (R 07/17) Page 1 of 6 Notice: Pursuant to s. 45.12(4)(g), Wis. Adm. Code, this application must be completed for shelter rental at a State Park. The Department of Natural Resources (DNR) cannot process your application unless you provide complete information. Personal information collected will be used for administrative purposes and may be provided to requesters to the extent required by Wisconsin's Open Records law [ss. 19.31-19.39, Wis. Stats.]. Credit card information will be kept confidential and will only be used to process this application. *This form does not include the amphitheaters at Rib Mountain and Mirror Lake state parks or the Gathering Spaces at Rib Mountain and High Cliff state parks. You must use the appropriate forms for those facilities. I. Applicant Information Group Name Name of Responsible Person Address City State ZIP Code Daytime Phone Number E-Mail Address II. Choice of Facility State Park, Forest or Recreation Area Number of People in Party Select a facility in order of preference. Your second choice is an alternative to your first choice if your first choice is not available. If you wish to have an alternative date and time for your first choice of facility do not enter a second choice. If a second choice facility is chosen the second choice date and time will be for that facility. Fees, facilities and availability is subject to change. Facility Open/Enclosed Capacity Accessible Water Electricity Toilet Grill *Number of hours (amphitheater only) ? Fee 1st Your choice of rental dates (up to 11 months in advance): 1st Choice Date Arrival Time Departure Time 2nd Choice Date Arrival Time Departure Time Facility Open/Enclosed Capacity Accessible Water Electricity Toilet Grill *Number of hours (amphitheater only) ? Fee 2nd Your choice of rental dates for 2nd facility (up to 11 months in advance): 1st Choice Date Arrival Time Departure Time 2nd Choice Date Arrival Time Departure Time III. -

Wisconsin's Wildlife Action Plan (2005-2015)

Wisconsin’s Wildlife Action Plan (2005-2015) IMPLEMENTATION: Priority Conservation Actions & Conservation Opportunity Areas Prepared by: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources with Assistance from Conservation Partners, June 30th, 2008 06/19/2008 page 2 of 93 Wisconsin’s Wildlife Action Plan (2005-2015) IMPLEMENTATION: Priority Conservation Actions & Conservation Opportunity Areas Acknowledgments Wisconsin’s Wildlife Action Plan is a roadmap of conservation actions needed to ensure our wildlife and natural communities will be with us in the future. The original plan provides an immense volume of data useful to help guide conservation decisions. All of the individuals acknowledged for their work compiling the plan have a continuous appreciation from the state of Wisconsin for their commitment to SGCN. Implementing the conservation actions is a priority for the state of Wisconsin. To put forward a strategy for implementation, there was a need to develop a process for priority decision-making, narrowing the list of actions to a more manageable number, and identifying opportunity areas to best apply conservation actions. A subset of the Department’s ecologists and conservation scientists were assigned the task of developing the implementation strategy. Their dedicated commitment and tireless efforts for wildlife species and natural community conservation led this document. Principle Process Coordinators Tara Bergeson – Wildlife Action Plan Implementation Coordinator Dawn Hinebaugh – Data Coordinator Terrell Hyde – Assistant Zoologist (Prioritization -

Mountain Bike Trails

Contents Using the Guide 2-3 On-Road Tours 4-25 Mountain Bike Trails 26-47 Bike Touring Trails 48-69 More Wisconsin Biking Trails 70-71 Wisconsin Bike Events 72-IBC Using the Guide Map Legend 94 Interstate Highway isconsin and biking were 51 US Highway made for each other! The 68 State Highway Badger State is recognized G County Highway as a national leader in recre- W Town Road (Paved) ational biking. An excellent road sys- tem, coupled with outstanding off-road Town Road (Gravel) terrain, make Wisconsin a true biking Bike Route: on State Highways adventure for everyone. Bike Route: on County Highways The Wisconsin Biking Guide gath- Bike Route: on Town Roads (Paved) ers a sampling of the wonderful biking Bike Route: on Town Roads (Gravel) experiences Wisconsin has to offer. Bike Touring Trail (Paved) Rides are divided into three categories, based on riding interest: on-road tours, Bike Touring Trail (Unpaved) mountain bike trails, and bike touring Off-road: Easy trails. Off-road: Moderate Often, a geographic area offers Off-road: Difficult more than one type of ride. The map Off-road: Single-Track on page 3 shows the location of ten on-road tours, ten mountain bike trails, Hiking Trail/Other Trail and ten bike touring trails. Pick a desti- ATV Trail nation, then check out the many ride County Lines options along the way. Railroad This is the seventh edition of the Park Boundary Wisconsin Biking Guide. The thirty Parking Lot trails and tours on these pages are a 2.9 part of more than 100 in our on-line Mileage Indicators collection. -

Sanitary Disposals Alabama Through Arkansas

SANITARY DispOSAls Alabama through Arkansas Boniface Chevron Kanaitze Chevron Alaska State Parks Fool Hollow State Park ALABAMA 2801 Boniface Pkwy., Mile 13, Kenai Spur Road, Ninilchik Mile 187.3, (928) 537-3680 I-65 Welcome Center Anchorage Kenai Sterling Hwy. 1500 N. Fool Hollow Lake Road, Show Low. 1 mi. S of Ardmore on I-65 at Centennial Park Schillings Texaco Service Tundra Lodge milepost 364 $6 fee if not staying 8300 Glenn Hwy., Anchorage Willow & Kenai, Kenai Mile 1315, Alaska Hwy., Tok at campground Northbound Rest Area Fountain Chevron Bailey Power Station City Sewage Treatment N of Asheville on I-59 at 3608 Minnesota Dr., Manhole — Tongass Ave. Plant at Old Town Lyman Lake State Park milepost 165 11 mi. S of St. Johns; Anchorage near Cariana Creek, Ketchikan Valdez 1 mi. E of U.S. 666 Southbound Rest Area Garrett’s Tesoro Westside Chevron Ed Church S of Asheville on I-59 Catalina State Park 2811 Seward Hwy., 2425 Tongass Ave., Ketchikan Mile 105.5, Richardson Hwy., 12 mi. N of on U.S. 89 at milepost 168 Anchorage Valdez Tucson Charlie Brown’s Chevron Northbound Rest Area Alamo Lake State Park Indian Hills Chevron Glenn Hwy. & Evergreen Ave., Standard Oil Station 38 mi. N of & U.S. 60 S of Auburn on I-85 6470 DeBarr Rd., Anchorage Palmer Egan & Meals, Valdez Wenden at milepost 43 Burro Creek Mike’s Chevron Palmer’s City Campground Front St. at Case Ave. (Bureau of Land Management) Southbound Rest Area 832 E. Sixth Ave., Anchorage S. Denali St., Palmer Wrangell S of Auburn on I-85 57 mi. -

Wisconsin Trails Network Plan 2001 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Iii

Wisconsin Trails Network Plan Open/Established Trail ○○○ Proposed Trail Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources PUB-PR-313 2003 TRAILS NETWORK PLAN TRAILS NETWORK Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Wisconsin 2003 Trails Network Plan First Printed in January 2001 Revised in March 2003 Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Box 7921, 101 S. Webster St. Madison, WI 53707 For more information contact the Bureau of Parks and Recreation at (608) 266-2181 The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources provides equal opportunity in its employment, programs, services, and functions under an Affirmative Action Plan. If you have any questions, please write to Equal Opportunity Office, Department of Interior, Washington, D.C. 20240. This publication is available in alternative format (large print, Braille, audio tape, etc.) upon request. Please call the Bureau of Parks and Recreation at (608) 266-2181. ii Wisconsin Trails Network Plan 2001 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii George E. Meyer, Secretary State Trails Council Steve Miller, Administrator, Lands Division Connie C. Loden, Hurley, Chair Susan Black, Director, Bureau of Parks and Christopher Kegel, Mequon, Vice Chair Recreation Michael F. Sohasky, Antigo, Secretary Jeffrey L. Butson, Madison Thomas Huber, Madison 1999 Guidance Team Mike McFadzen, Plymouth Bill Pfaff, New Lisbon Dale Urso, Land Leader, Northern Region David W. Phillips, Madison ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Susan Black, Director, Bureau of Parks and Joe Parr, Brodhead Recreation Robert Roden, Director, Bureau of Lands and Facilities Others Involved -

Northern Gun Deer Hunters Need to Check Status of Units Where They

OCTOBER 2009 VOLUME 36 NUMBER 10 NorthernGun Deer Hunters Need to Check StatusofUnits WhereTheyWill Hunt Free antlerless deer hunting permits are not usable in most of northern Wisconsin POONER –Aftermany years of lib- $20eachfor non-residents.Alimited number and purchase the eral antlerless deer hunting opportu- of permits are available for eachunit, and proper license Snitiesinnorthern Wisconsin, wildlife many units have already sold out. Permit and tags accord- officials saygun hunters who plan on hunting availabilityislisted on theDNR Website. ingly,” he said. in northern deer management units(DMUs) Archery antlerless deer carcass tags are He notes many thisfall needtocarefullycheck the status of not Herd Control tags and arevalidinall western and the area where they hunt. In most cases they units statewide,but mayonly be filledusing eastern counties will not be abletouse the freeherd control legal archerygear. still have Herd antlerless permits they receive with their “Werealize this is ahuge change for deer Control units, licenseasthey have in recent years. hunters in the north thisyear,” Zeckmeister the southern It willbean“old fashioned” buck-onlygun said,“but out deer programisdesigned to countieshave deer season in manynorthern units this year, quickly respondtochanges in deer popula- CWD units andafew units arenon-quota. said Mike Zeckmeister,the DNR Northern tions, like lower deer numbers northern Also,Zeckmeister added, thatbecause Region wildlife supervisor. Hunters and last hunters reported last year.” most of the units