Child Custody Evaluators' Beliefs About

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expert Evidence in Favour of Shared Parenting 2 of 12 Shared Parenting: Expert Evidence

Expert evidence in favour of shared parenting 2 of 12 Shared Parenting: Expert Evidence Majority View of Psychiatrists, Paediatricians and Psychologists The majority view of the psychiatric and paediatric profession is that mothers and fathers are equals as parents, and that a close relationship with both parents is necessary to maximise the child's chances for a healthy and parents productive life. J. Atkinson, Criteria for Deciding Child Custody in the Trial and Appellate Courts, Family Law Quarterly, Vol. XVIII, No. 1, American both Bar Association (Spring 1984). In a report that “summarizes and evaluates the major research concerning joint custody and its impact on children's welfare”, the American Psychological Association (APA) concluded that: “The research reviewed supports the conclusion that joint custody is parent is associated with certain favourable outcomes for children including father involvement, best interest of the child for adjustment outcomes, child support, reduced relitigation costs, and sometimes reduced parental conflict.” best The APA also noted that: the “The need for improved policy to reduce the present adversarial approach that has resulted in primarily sole maternal custody, limited father involvement and maladjustment of both children and parents is critical. Increased mediation, joint custody, and parent education are supported for this policy.” Report to the US Commission on Child and Family Welfare, American Psychological Association (June 14, 1995) The same American Psychological Association adopted -

Behaviour and Characteristics of Perpetrators of Online-Facilitated Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation a Rapid Evidence Assessment

Behaviour and Characteristics of Perpetrators of Online-facilitated Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation A Rapid Evidence Assessment Final Report Authors: Jeffrey DeMarco, Sarah Sharrock, Tanya Crowther and Matt Barnard January 2018 Prepared for: Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) Disclaimer: This is a rapid evidence assessment prepared at IICSA’s request. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors alone. At NatCen Social Research we believe that social research has the power to make life better. By really understanding the complexity of people’s lives and what they think about the issues that affect them, we give the public a powerful and influential role in shaping decisions and services that can make a difference to everyone. And as an independent, not for profit organisation we’re able to put all our time and energy into delivering social research that works for society. NatCen Social Research 35 Northampton Square London EC1V 0AX T 020 7250 1866 www.natcen.ac.uk A Company Limited by Guarantee Registered in England No.4392418. A Charity registered in England and Wales (1091768) and Scotland (SC038454) This project was carried out in compliance with ISO20252 © Crown copyright 2018 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.iicsa.org.uk. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] Contents Glossary of terms ............................................................. -

Motivations and Impression Management

MOTIVATIONS AND IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT: PREDICTORS OF SOCIAL NETWORKING SITE USE AND USER BEHAVIOR A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by Kara Krisanic Dr. Shelly Rodgers, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2008 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled MOTIVATIONS AND IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT: PREDICTORS OF SOCIAL NETWORKING SITE USE AND USER BEHAVIOR presented by Kara Krisanic, a candidate for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Shelly Rodgers, Committee Chair ________________________________________ Dr. Margaret Duffy, Committee Member and Advisor ________________________________________ Dr. Paul Bolls, Committee Member ________________________________________ Dr. Jennifer Aubrey, Outside Committee Member ________________________________________ DEDICATION I dedicate the following thesis to my parents, Rita and Julius, without whom nothing in my life would be possible. Your love, encouragement, support and guidance have always served as the driving force behind my motivation to achieve my highest goals. Words cannot express the overwhelming gratitude I have for the life you have provided me. I will forever carry with me, the lessons you have instilled in my heart. Thank you and I love you, yesterday, today and always. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my entire thesis committee for their gentle guidance, continuous mentoring, and undying support throughout the completion of my thesis and graduate degree. Each of your unique contributions encouraged me to reach further and to dig deeper than I ever thought myself capable. -

Chickasaw Nation Code Title 6, Chapter 2

Domestic Relations & Families (Amended as of 08/20/2021) CHICKASAW NATION CODE TITLE 6 "6. DOMESTIC RELATIONS AND FAMILIES" CHAPTER 1 MARRIAGE ARTICLE A DISSOLUTION OF MARRIAGE Section 6-101.1 Title. Section 6-101.2 Jurisdiction. Section 6-101.3 Areas of Jurisdiction. Section 6-101.4 Applicable Law. Section 6-101.5 Definitions of Marriage; Common Law Marriage. Section 6-101.6 Actions That May Be Brought; Remedies. Section 6-101.7 Consanguinity. Section 6-101.8 Persons Having Capacity to Marry. Section 6-101.9 Marriage Between Persons of Same Gender Not Recognized. Section 6-101.10 Grounds for Divorce. Section 6-101.11 Petition; Summons. Section 6-101.12 Notice of Pendency Contingent upon Service. Section 6-101.13 Special Notice for Actions Pending in Other Courts. Section 6-101.14 Pleadings. Section 6-101.15 Signing of Pleadings. Section 6-101.16 Defense and Objections; When and How Presented; by Pleadings or Motions; Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings. Section 6-101.17 Reserved. Section 6-101.18 Lost Pleadings. Section 6-101.19 Reserved. Section 6-101.20 Reserved. Section 6-101.21 Reserved. Section 6-101.22 Reserved. Section 6-101.23 Reserved. Page 6-1 Domestic Relations & Families Section 6-101.24 Reserved. Section 6-101.25 Reserved. Section 6-101.26 Reserved. Section 6-101.27 Summons, Time Limit for Service. Section 6-101.28 Service and Filing of Pleadings and Other Papers. Section 6-101.29 Computation and Enlargement of Time. Section 6-101.30 Legal Newspaper. Section 6-101.31 Answer May Allege Cause; New Matters Verified by Affidavit. -

Tactics of Impression Management: Relative Success on Workplace Relationship Dr Rajeshwari Gwal1 ABSTRACT

The International Journal of Indian Psychology ISSN 2348-5396 (e) | ISSN: 2349-3429 (p) Volume 2, Issue 2, Paper ID: B00362V2I22015 http://www.ijip.in | January to March 2015 Tactics of Impression Management: Relative Success on Workplace Relationship Dr Rajeshwari Gwal1 ABSTRACT: Impression Management, the process by which people control the impressions others form of them, plays an important role in inter-personal behavior. All kinds of organizations consist of individuals with variety of personal characteristics; therefore those are important to manage them effectively. Identifying the behavior manner of each of these personal characteristics, interactions among them and interpersonal relations are on the basis of the impressions given and taken. Understanding one of the important determinants of individual’s social relations helps to get a broader insight of human beings. Employees try to sculpture their relationships in organizational settings as well. Impression management turns out to be a continuous activity among newcomers, used in order to be accepted by the organization, and among those who have matured with the organization, used in order to be influential (Demir, 2002). Keywords: Impression Management, Self Promotion, Ingratiation, Exemplification, Intimidation, Supplication INTRODUCTION: When two individuals or parties meet, both form a judgment about each other. Impression Management theorists believe that it is a primary human motive; both inside and outside the organization (Provis,2010) to avoid being evaluated negatively (Jain,2012). Goffman (1959) initially started with the study of impression management by introducing a framework describing the way one presents them and how others might perceive that presentation (Cole, Rozelle, 2011). The first party consciously chooses a behavior to present to the second party in anticipation of a desired effect. -

SAFETY FOCUSED PARENTING PLAN GUIDE for Parents

SAFETY FOCUSED PARENTING PLAN GUIDE for Parents Developed by the OREGON JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT STATE FAMILY LAW ADVISORY COMMITTEE — Parenting Plan Outreach Workgroup and the OFFICE OF THE STATE COURT ADMINISTRATOR Court Programs and Services Division JUNE 2003 - VERSION #4 CONTACT and COPY INFORMATION For more information about this Guide, contact: COURT PROGRAMS AND SERVICES DIVISION Office of State Court Administrator 1163 State Street Salem, OR 97301-2563 (503) 986-6423 Fax: (503) 986-6419 E-Mail: [email protected] To download copies of this Guide, go to the Website: http://courts.oregon.gov/familylaw and click on the “Parenting Plans” link. COPYRIGHT NOTICE. Copyright 2003, for the use and benefit of the Oregon Judicial Department, all rights reserved. Permission to all Oregon courts is granted for use and resale of this Guide and its component sections for the cost of printing or copying. You may reproduce or copy this material for personal use or non-profit educational purposes but not for resale or other for-profit distribution unless you have permission from the Oregon Judicial Department. Safety Focused Parenting Plan Do you need a Safety Focused Plan? This list can help you decide. Has the other parent: < acted as though violent behavior toward you or your child(ren) is OK in some situations? < damaged or destroyed property or pets during an argument? < threatened to commit suicide? < pushed, slapped, kicked, punched or physically hurt you or your child(ren)? < had problems with alcohol or other drugs? < needed medication to be safe around others? < threatened not to return or not returned your child(ren)? < used weapons to threaten or hurt people? < threatened to kill you, your child(ren) or anyone else? < sexually abused anyone by force, threat of force, or intimidation? < been served a protection or no contact order? < been arrested for harming or threatening to harm you or anyone else? If you answered yes to any of these questions, please continue to take your safety, and your children’s safety, seriously. -

Proactive Workplace Bullying in Teams: Test of a Rational and Moral Model of Aggression

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Science and Health Theses and Dissertations College of Science and Health Summer 8-20-2017 Proactive Workplace Bullying in Teams: Test of a Rational and Moral Model of Aggression Anthony S. Colaneri DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/csh_etd Part of the Industrial and Organizational Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Colaneri, Anthony S., "Proactive Workplace Bullying in Teams: Test of a Rational and Moral Model of Aggression" (2017). College of Science and Health Theses and Dissertations. 232. https://via.library.depaul.edu/csh_etd/232 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Science and Health at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Science and Health Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: PROACTIVE WORKPLACE BULLYING IN TEAMS Proactive Workplace Bullying in Teams: Test of a Rational and Moral Model of Aggression A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Anthony S. Colaneri 7/4/2017 Department of Psychology College of Science and Health DePaul University Chicago, Illinois PROACTIVE WORKPLACE BULLYING IN TEAMS ii Thesis Committee Suzanne Bell, Ph.D., Chairperson Douglas Cellar, PhD., Reader PROACTIVE WORKPLACE BULLYING IN TEAMS iii Acknowledgments I would like to express my appreciation and gratitude to Dr. Suzanne Bell for her invaluable guidance and support throughout this process. I would also like to thank Dr. Douglas Cellar for his guidance and added insights in the development of this thesis. -

Child Custody Arrangements: Say What You Mean, Mean What You Say

Land & Water Law Review Volume 31 Issue 2 Article 15 1996 Child Custody Arrangements: Say What You Mean, Mean What You Say DeNece Day Koenigs Kimberly A. Harris Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uwyo.edu/land_water Recommended Citation Koenigs, DeNece Day and Harris, Kimberly A. (1996) "Child Custody Arrangements: Say What You Mean, Mean What You Say," Land & Water Law Review: Vol. 31 : Iss. 2 , pp. 591 - 621. Available at: https://scholarship.law.uwyo.edu/land_water/vol31/iss2/15 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Law Archive of Wyoming Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Land & Water Law Review by an authorized editor of Law Archive of Wyoming Scholarship. Koenigs and Harris: Child Custody Arrangements: Say What You Mean, Mean What You Say Comment CHILD CUSTODY ARRANGEMENTS: Say What You Mean, Mean What You Say INTRODUCTION In Wyoming, custody battles place judges and court commissioners in King Solomon's' position nearly everyday as they are asked to split children between divorcing parents.2 Of course, judges and commissioners do not wield swords, but they do use legal terms which are often inade- quate and misused.' Unfortunately, the modem day result, though not as graphic as that from the Bible, is just as severe. As many as one in every two marriages will result in divorce.4 Thirty percent of children today will be the focus of a custody decision., For too many of these children, their lives will be adversely affected by an improper custody arrangement caused by the erroneous use of the term "joint custody." 6 The law as it stands in Wyoming does not adequately consider the non-legal aspects of custody or give practitioners and judges the guidance necessary to make appropriate custody determinations.' Gurney v. -

Articles Contractualizing Custody

ARTICLES CONTRACTUALIZING CUSTODY Sarah Abramowicz* Many scholars otherwise in favor of the enforcement of family contracts agree that parent-child relationships should continue to prove the exception to any contractualized family law regime. This Article instead questions the continued refusal to enforce contracts concerning parental rights to children’s custody. It argues that the refusal to enforce such contracts contributes to a differential treatment of two types of families: those deemed “intact”—typically consisting of two married parents and their offspring—and those deemed non-intact. Intact families are granted a degree of freedom from government intervention, provided that there is no evidence that children are in any danger of harm. Non-intact families, by contrast, are subject to the perpetual threat of intervention, even in the absence of harm. The result of this two-tier system is that non-intact families are denied the autonomy and stability that intact families enjoy, to the detriment of parents and children alike. The goal of this Article is to address inconsistent scholarly approaches to custody agreements, on the one hand, and parentage agreements, on the other. Marital agreements about children are largely unenforceable, and even scholars who otherwise favor the enforcement of marital agreements largely approve of this approach, concurring that a court should be able to override a contract concerning children’s custody if it finds that enforcement is not in the children’s best interests. By contrast, those who write about parentage agreements, such as those made in the context of assisted reproductive technology or by unmarried, single, or multiple (i.e., more than two) parents, are more likely to favor the enforcement of such agreements. -

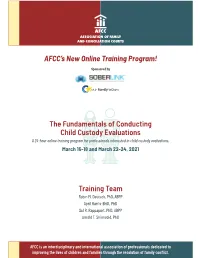

The Fundamentals of Conducting Child Custody Evaluations AFCC's

ASSOCIATION OF FAMILY AND CONCILIATION COURTS AFCC’s New Online Training Program! Sponsored by The Fundamentals of Conducting Child Custody Evaluations A 24-hour online training program for professionals interested in child custody evaluations. March 16-18 and March 22-24, 2021 Training Team Robin M. Deutsch, PhD, ABPP April Harris-Britt, PhD Sol R. Rappaport, PhD, ABPP Arnold T. Shienvold, PhD AFCC is an interdisciplinary and international association of professionals dedicated to improving the lives of children and families through the resolution of family conflict. The Fundamentals of Conducting Child Custody Evaluations A 24-hour online training program for professionals interested in child custody evaluations. March 16-18 and March 22-24, 2021 AFCC is pleased to introduce a new, comprehensive child custody evaluation (CCE) training, conducted online by a team of leading practitioners and trainers. The program will take place in two segments per day, two hours each. Recordings of all sessions will be available for registrants. This program will include a complete overview of the child custody evaluation process, including: Definition of the purpose and roles of the child custody evaluator Specifics of the evaluation process, including interviewing, recordkeeping, and use of technology Implications of intimate partner violence and resist-refuse dynamics Updates on the current research Development of parenting plans Review of cultural considerations, bias, and ethical issues Utilization of psychological testing Best practices for report writing and testifying Participants will learn the difference between a forensic role and clinical role, how to review court orders and determine which information should be obtained, strategies for interviewing adults and children, how to assess coparenting issues, how to develop and test multiple hypotheses, and how to craft recommendations. -

Joint Versus Sole Physical Custody What Does the Research Tell Us About Children’S Outcomes?

feature article Joint Versus Sole Physical Custody What Does the Research Tell Us About Children’s Outcomes? by Linda Nielsen, Ph.D. Do children fare better or worse in joint physical cus- favorably in terms of children's best interests and perceived it as tody (JPC) families where they live with each parent at least having no impact on legal or personal conflicts between parents.1 35% of the time than in sole physical custody (SPC) families But are children’s outcomes better in JPC than SPC fami- where they live primarily or exclusively with one parent? This lies –especially if their parents do not get along well as co-par- question assumes even more importance as JPC has become ents? And if JPC children have better outcomes, is this because increasingly common in the U.S. and abroad. For example, in their parents have more money, less conflict, better parenting Wisconsin JPC increased from 5% in 1986 to more than 35% skills or higher quality relationships with their children before in 2012. And as far back as 2008, 46% of separated parents in they separate? Put differently, are JPC parents “exceptional” Washington state and 30% in Arizona had JPC arrangements. because they get along better than SPC parents and mutually JPC has risen to nearly 50% in Sweden, 30% in Norway and agree to the custody plan from the outset? the Netherlands, 37% in Belgium, 26% in Quebec and 40% in British Columbia and the Catalonia region of Spain. Those who have expressed misgivings about JPC have made a number of claims that they report are based on the research. -

Impression Management and Its Interaction with Emotional Intelligence and Locus of Control: Two-Sample Investigation

R M B www.irmbrjournal.com September 2016 R International Review of Management and Business Research Vol. 5 Issue.3 I Impression Management and Its Interaction with Emotional Intelligence and Locus of Control: Two-Sample Investigation TAREK A. EL BADAWY Assistant Professor of Management, Auburn University at Montgomery, Alabama. Email: [email protected] ISIS GUTIÉRREZ-MARTÍNEZ Universidad de las Américas Puebla, Santa Catarina Mártir S/N. Email: [email protected] MARIAM M. MAGDY Research Associate, German University in Cairo, Egypt. Email: [email protected] Abstract The art of self-presentation is inherently important for exploration. Tight markets and fierce competition force employees to think about presenting themselves in the best way that ensures their continuous employment. In this study, an attempt was made to compare between employees of Mexico and Egypt with regard to the types of impression management strategies they use. Interactions between impression management, emotional intelligence and locus of control were also investigated. Several significant insights were reached using the Mann-Whitney U test. Further analyses, implications and future research recommendations are provided. Key Words: Self-Presentation; Emotions; Perception; Comparative Study; Middle East; Latin America. Introduction Impression management or the technique of self-presentation was the term first introduced by Goffman in the 1950s. Impression management is the individual’s attempt to manipulate how others see him/her as if the individual is an actor on stage trying to convey a certain character to the spectators. Originally a construct in Psychology, scholars of organizational behaviour adopted it in their pursuit to understand the different complicated relationships between employees in organizations (Ashford and Northcraft, 1992; Leary and Kowalski, 1990).