Conversion Growth of Protestant Churches Dissertatie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don't Leave the Cake Unturned

EDITORIAL The problem is that it looks so good, but only from one side. One of the current USA presidential candidates has trumped Don’t Leave Norman as his mentor. I reproduce here a quote from an article I read recently: The Cake Unturned “Christianity is a religion of losers. To the weak and humble, it By Revd Canon Terry Wong offers a stripped and humiliated Lord. To those without reason for optimism, it holds up the cross as a sign of hope. To anyone I recall preaching on Hosea 7:8 almost 20 years ago. who does not win at life, it promises that whoever loses his life for Christ’s sake shall find it. At its center stands a truth that we are prone to forget. There are people who cannot be “Ephraim is a cake not turned.” made into winners, no matter how positive their thinking. They need something more paradoxical and cruciform.” (Matthew Schmitz, First Things, August 2016) f you have cooked or baked long enough, you would probably Ibe acquainted with the dreadful experience of turning out Due to this mixture in our hearts, we need to come before God food that looks cooked, only to discover that it is cooked only constantly in brokenness and humility. The Bible constantly on one side. seeks to alert us to our mixed condition. God calls our attention to - not away from - it. Moving from the kitchen to something that is more visceral in our urban jungle, imagine a half-completed high-rise Jeremiah 17:9 despairs, “The heart is deceitful above all things, building. -

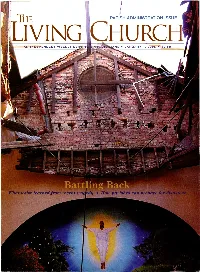

PARISH ADMINISTRATION ISSUE 1Llving CHURC----- 1-.··,.:, I

1 , THE PARISH ADMINISTRATION ISSUE 1llVING CHURC----- 1-.··,.:, I, ENDURE ... EXPLORE YOUR BEST ACTIVE LIVING OPTIONS AT WESTMINSTER COMMUNITIES OF FLORIDA! 0 iscover active retirement living at its finest. Cf oMEAND STAY Share a healthy lifestyle with wonderful neighbors on THREE DAYS AND TWO any of our ten distinctive sun-splashed campuses - NIGHTS ON US!* each with a strong faith-based heritage. Experience urban excitement, ATTENTION:Episcopalian ministers, missionaries, waterfront elegance, or wooded Christian educators, their spouses or surviving spouses! serenity at a Westminster You may be eligible for significant entrance fee community - and let us assistance through the Honorable Service Grant impress you with our signature Program of our Westminster Retirement Communities LegendaryService TM. Foundation. Call program coordinator, Donna Smaage, today at (800) 948-1881 for details. *Transportation not included. Westminster Communities of Florida www.WestminsterRetirement.com Comefor the Lifestyle.Stay for a Lifetime.T M 80 West Lucerne Circle • Orlando, FL 32801 • 800.948.1881 The objective of THELIVI N G CHURCH magazine is to build up the body of Christ, by describing how God is moving in his Church ; by reporting news of the Church in an unbiased manner; and by presenting diverse points of view. THIS WEEK Features 16 2005 in Review: The Church Begins to Take New Shape 20 Resilient People Coas1:alChurches in Mississippi after Hurricane Katrina BYHEATHER F NEWfON 22 Prepare for the Unexpected Parish sUIVivalcan hinge on proper planning BYHOWARD IDNTERTHUER Opinion 24 Editor's Column Variety and Vitality 25 Editorials The Holy Name 26 Reader's Viewpoint Honor the Body BYJONATHAN B . -

Goethe-Institut Thailand เขียนโดยมาร์ติน ชัค์ท รอยรำลึกเยอรมันในกรุงเทพฯ และรอยรำลึกไทยในเยอรมัน

ร่องรอยเยอรมันในกรุงเทพฯ และ ร่องรอยประเทศไทยในเบอร์ลิน ร่องรอยเยอรมันในกรุงเทพฯ GERMAN TRACES IN BANGKOK, THAI TRACES IN BERLIN THAILÄNDISCHE BERLIN BANGKOK, DEUTSCHE IN SPUREN IN SPUREN Martin Schacht mit Vorwort von Maren Niemeyer 60 DEUTSCHE SPUREN IN BANGKOK, THAILÄNDISCHE SPUREN IN BERLIN GERMAN TRACES IN BANGKOK, THAI TRACES IN BERLIN ร่องรอยเยอรมันในกรุงเทพฯ และ ร่องรอย ประเทศไทยในเบอร์ลิน Goethe-Institut Thailand Goethe-Institut Eine Publikation zum 60. Jubiläum Photo: © Goethe-Institut Thailand Neufert / Detlev. F. des Goethe-Institut Thailand Umschlag: Traditioneller Thai Tanz vor dem Brandenburger Tor in Berlin aus dem Film Sabai, Sabai Deutschland Cover: Traditional Thai dance in front of the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin from the film Sabai, Sabai Deutschland หน้าปก นางร�าไทยหน้าประตูบรันเดิร์นเบิร์ก ณ กรุงเบอร์ลิน จากภาพยนตร์ Sabai, Sabai Deutschland DEUTSCHE SPUREN IN BANGKOK, THAILÄNDISCHE SPUREN IN BERLIN GERMAN TRACES IN BANGKOK, THAI TRACES IN BERLIN ร่องรอยเยอรมันในกรุงเทพฯ และ ร่องรอย ประเทศไทยในเบอร์ลิน 4 Vorwort Vorwort 5 Das Goethe-Institut Thailand hat sich anlässlich seines 60. VORWORT Jubiläums zum Ziel gesetzt, diese Orte und ihre bewegenden Geschichten sichtbarer zu machen. Wir freuen uns, Ihnen mit diesem Büchlein eine Vorab-Ver- öffentlichung des multimedialen Städte-Spaziergangs „Deutsche Spuren in Bangkok, thailändische Spuren in Berlin“ zu präsentieren. Als Autor konnten wir den in Berlin und Bangkok lebenden Wussten Sie, dass der Schwager von Thomas Mann einst in Publizisten Martin Schacht gewinnen. Lassen Sie sich von ihm Bangkok lebte und die Elektromusikerin Nakadia, eine der erfolg- entführen an diese besonderen Plätze, die ein beindruckendes reichsten DJ - Stars des berühmten Berliner Berghain-Clubs, aus Zeugnis ablegen über die abwechslungsreichen Episoden der Thailand stammt? Oder dass die thailändische Nationalhymne von deutsch-thailändischen Geschichte. einem Deutschen komponiert wurde und dass in Berlin das junge Besuchen sie z.B. -

The Consecration and Enthronement of the Rt Revd Dr Titus Chung As the 10Th Bishop of Singapore on Sunday, 18 October 2020 Contents

Diocesan Diocese of Singapore • www.anglican.org.sg MCI (P) 060/03/2020 Issue 274 | November 2020 DIGEST The consecration and enthronement of The Rt Revd Dr Titus Chung as the 10th Bishop of Singapore on Sunday, 18 October 2020 Contents EDITORIAL TEAM 01 Editorial ADVISOR The Rt Revd Dr Titus Chung 02 Bishop's Synod Address EDITORS 05 Church in Singapore: Consecration and Enthronement Revd Canon Terry Wong Mrs Karen Wong Service Ms Sasha Michael 09 Church in Singapore: Thanksgiving Service DESIGNERS Ms Joyce Ho 12 Teaching Article: Spiritual Formation in a Leader’s Life Mr Daniel Ng email: [email protected] website: FROM OUR MINISTRY FRONTS www.anglican.org.sg 16 Deaneries and Global Missions 26 Youth and Young Adults 30 Anglican Schools 36 Community Services 45 Chinese-Speaking Work 46 Indian-Speaking Work 48 Parish Spotlight: Chapel of the Holy Spirit 51 Singapore Highlights 54 Diocesan News 59 Diocesan Listings Diocesan Digest © The Diocese of Singapore All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by an means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, and recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. EDITORIAL “For though you have countless guides in Christ, you do not have many fathers. For I became your father in Christ Jesus through the gospel.” 1 Corinthians 4:15 By Revd Canon Terry Wong n my editorial piece for the December 2012 issue of the Diocesan Digest, I had reflected on the passing of the baton from Bishop John IChew to Bishop Rennis Ponniah: Reflecting on the years under the ministry of Bishop John Chew, I can vividly recall how I visited some friends with him in Edinburgh.