Turkey and Russia in Syrian War: Hostile Friendship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Arab Spring Or Arab Winter (Or Both)? Implications for U.S. Policy

www.pomed.org ♦ 1820 Jefferson Place NW, Suite 400 ♦ Washington, DC 20036 “Arab Spring or Arab Winter (or Both)? Implications for U.S. Policy” The Middle East Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars 1300 Pennsylvania Ave., NW Tuesday July 19th, 9:30 a.m.-11:00 a.m. On Tuesday, the Middle East Program hosted an event at the Woodrow Wilson Center entitled “Arab Spring or Arab Winter (or Both)? Implications for U.S. Policy” featuring expert panelists: Marwan Muasher, Vice President for studies at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; Ellen Laipson, President and CEO of the Stimson Center; Rami G.Khouri, Director of the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut; and Aaron David Miller, Public Policy Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center. Ellen Laipson asserted that the movement in the Middle East has surpassed a „season‟ and will prove to be an enduring and prevailing issue in global politics. She stated that overall, the movement was a “net positive for the region” although there is still unsettling uncertainty in the area. She also discussed a global transition that is taking place, where middle powers are rising and the U.S.‟ regional influences are diminishing. Also, she proposed the question of how the U.S. can initiate conversations with countries in the Middle East which haven‟t faced a revolutionary transition yet. Lastly, Laipson discussed how the U.S., as a part of the international community whole, can continue to promote democracy and institution-building in transitional governments. She noted that the security agenda mustn‟t be dismissed, and that security sector reform needs to be a part of the overall effort of the reform process. -

Squaring the Circles in Syria's North East

Squaring the Circles in Syria’s North East Middle East Report N°204 | 31 July 2019 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 149 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Search for Middle Ground ......................................................................................... 3 A. The U.S.: Caught between Turkey and the YPG ........................................................ 3 1. Turkey: The alienated ally .................................................................................... 4 2. “Safe zone” or dead end? The buffer debate ........................................................ 8 B. Moscow’s Missed Opportunity? ................................................................................. 11 C. The YPG and Damascus: Playing for Time ................................................................ 13 III. A War of Attrition with ISIS Remnants ........................................................................... 16 A. The SDF’s Approach to ISIS Detainees ..................................................................... 16 B. Deteriorating Relations between the SDF and Local Tribes .................................... -

Adaptation Strategies of Islamist Movements April 2017 Contents

POMEPS STUDIES 26 islam in a changing middle east Adaptation Strategies of Islamist Movements April 2017 Contents Understanding repression-adaptation nexus in Islamist movements . 4 Khalil al-Anani, Doha Institute for Graduate Studies, Qatar Why Exclusion and Repression of Moderate Islamists Will Be Counterproductive . 8 Jillian Schwedler, Hunter College, CUNY Islamists After the “Arab Spring”: What’s the Right Research Question and Comparison Group, and Why Does It Matter? . 12 Elizabeth R. Nugent, Princeton University The Islamist voter base during the Arab Spring: More ideology than protest? . .. 16 Eva Wegner, University College Dublin When Islamist Parties (and Women) Govern: Strategy, Authenticity and Women’s Representation . 21 Lindsay J. Benstead, Portland State University Exit, Voice, and Loyalty Under the Islamic State . 26 Mara Revkin, Yale University and Ariel I. Ahram, Virginia Tech The Muslim Brotherhood Between Party and Movement . 31 Steven Brooke, The University of Louisville A Government of the Opposition: How Moroccan Islamists’ Dual Role Contributes to their Electoral Success . 34 Quinn Mecham, Brigham Young University The Cost of Inclusion: Ennahda and Tunisia’s Political Transition . 39 Monica Marks, University of Oxford Regime Islam, State Islam, and Political Islam: The Past and Future Contest . 43 Nathan J. Brown, George Washington University Middle East regimes are using ‘moderate’ Islam to stay in power . 47 Annelle Sheline, George Washington University Reckoning with a Fractured Islamist Landscape in Yemen . 49 Stacey Philbrick Yadav, Hobart and William Smith Colleges The Lumpers and the Splitters: Two very different policy approaches on dealing with Islamism . 54 Marc Lynch, George Washington University The Project on Middle East Political Science The Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS) is a collaborative network that aims to increase the impact of political scientists specializing in the study of the Middle East in the public sphere and in the academic community . -

Syrian Arab Republic

Syrian Arab Republic News Focus: Syria https://news.un.org/en/focus/syria Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Syria (OSES) https://specialenvoysyria.unmissions.org/ Syrian Civil Society Voices: A Critical Part of the Political Process (In: Politically Speaking, 29 June 2021): https://bit.ly/3dYGqko Syria: a 10-year crisis in 10 figures (OCHA, 12 March 2021): https://www.unocha.org/story/syria-10-year-crisis-10-figures Secretary-General announces appointments to Independent Senior Advisory Panel on Syria Humanitarian Deconfliction System (SG/SM/20548, 21 January 2021): https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sgsm20548.doc.htm Secretary-General establishes board to investigate events in North-West Syria since signing of Russian Federation-Turkey Memorandum on Idlib (SG/SM/19685, 1 August 2019): https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/sgsm19685.doc.htm Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels V Conference, 29-30 March 2021 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2021/03/29-30/ Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels IV Conference, 30 June 2020: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2020/06/30/ Third Brussels conference “Supporting the future of Syria and the region”, 12-14 March 2019: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2019/03/12-14/ Second Brussels Conference "Supporting the future of Syria and the region", 24-25 April 2018: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2018/04/24-25/ -

After the Revolution: the EU and the Arab Transition

After the Revolution: The EU and the Arab Transition Timo Behr Policy 54 Paper Policy After the Revolution: 54 The EU and the Arab Transition paper Timo Behr Timo BEHR Timo Behr is a Research Fellow at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs (FIIA) in Helsinki, where he heads FIIA’s research project on “The Middle East in Transition.” He is also an Associate Fellow with Notre Europe’s “Europe and World Governance” programme. Timo holds a PhD and MA in International Relations from the School of Advances International Studies of the Johns Hopkins University in Washington DC and has previously held positions with Notre Europe, the World Bank Group and the Global Public Policy Institute (GPPi) in Berlin. His recent publications include an edited volume on “The EU’s Options in a Changing Middle East” (FIIA, 2011), as well as a number of academic articles, policy briefs and commentaries on Euro-Mediterranean relations. AFTER THE REVOLUTION: THE EU AND THE ARAB TRANSITION Notre Europe Notre Europe is an independent think tank devoted to European integration. Under the guidance of Jacques Delors, who created Notre Europe in 1996, the association aims to “think a united Europe.” Our ambition is to contribute to the current public debate by producing analyses and pertinent policy proposals that strive for a closer union of the peoples of Europe. We are equally devoted to promoting the active engagement of citizens and civil society in the process of community construction and the creation of a European public space. In this vein, the staff of Notre Europe directs research projects; produces and disseminates analyses in the form of short notes, studies, and articles; and organises public debates and seminars. -

Middle East Factors

Middle East trategically situated at the intersection of In a way not understood by many in the SEurope, Asia, and Africa, the Middle East West, religion remains a prominent fact of dai- has long been an important focus of United ly life in the modern Middle East. At the heart States foreign policy. U.S. security relation- of many of the region’s conflicts is the friction ships in the region are built on pragmatism, within Islam between Sunnis and Shias. This shared security concerns, and economic in- friction dates back to the death of the Prophet terests, including large sales of U.S. arms to Muhammad in 632 AD.2 Sunni Muslims, who countries in the region that are seeking to form the majority of the world’s Muslim popu- defend themselves. The U.S. also maintains a lation, hold power in most of the Arab coun- long-term interest in the Middle East that is tries in the Middle East. related to the region’s economic importance as Viewing the current instability in the Mid- the world’s primary source of oil and gas. dle East through the lens of a Sunni–Shia con- The region is home to a wide array of cul- flict, however, does not show the full picture. tures, religions, and ethnic groups, including The cultural and historical division between Arabs, Jews, Kurds, Persians, and Turks, among Persians and Arabs has reinforced the Sunni– others. It also is home to the three Abrahamic Shia split. The mutual distrust of many Arab/ religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Sunni powers and the Persian/Shia power in addition to many smaller religions like the (Iran), compounded by clashing national and Bahá’í, Druze, Yazidi, and Zoroastrian faiths. -

The Future of Turkish-Western Relations: Toward a Strategic Plan

The Future of Turkish-Western Relations Toward a Strategic Plan Zalmay Khalilzad Ian O. Lesser F. Stephen Larrabee R Center for Middle East Public Policy • National Security Research Division Prepared for the Smith Richardson Foundation The research described in this report was sponsored by the Smith Richardson Foundation and RAND’s Center for Middle East Public Policy (CMEPP). The research was conducted within the Inter- national Security and Defense Policy Center of RAND’s National Security Research Division. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Khalilzad, Zalmay. The future of Turkish-Western relations : toward a strategic plan / Zalmay Khalilzad, Ian Lesser, F. Stephen Larrabee. p. cm. “MR-1241-SRF.” ISBN 0-8330-2875-8 1. Turkey—Foreign relations—Europe. 2. Europe—Foreign relations—Turkey. 3. Turkey—Foreign relations—United States. 4. United States—Foreign relations—Turkey. I. Lesser, Ian O., 1957– II. Larrabee, F. Stephen. III. Title. DR479.E85 K47 2000 327.5610171'3—dc21 00-059051 RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND® is a registered trademark. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. © Copyright 2000 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from RAND. Published 2000 by RAND 1700 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138 1200 South Hayes Street, Arlington, VA 22202-5050 RAND URL: http://www.rand.org/ To order RAND documents or to obtain additional information, contact Distribution Services: Telephone: (310) 451-7002; Fax: (310) 451-6915; Internet: [email protected] PREFACE At the dawn of a new century, Turkish-Western relations have also entered a new era. -

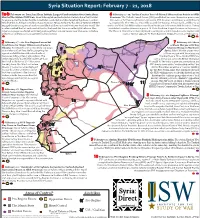

Syria SITREP Map 07

Syria Situation Report: February 7 - 21, 2018 1a-b February 10: Israel and Iran Initiate Largest Confrontation Over Syria Since 6 February 9 - 15: Turkey Creates Two Additional Observation Points in Idlib Start of the Syrian Civil War: Israel intercepted and destroyed an Iranian drone that violated Province: The Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) established two new observation points near its airspace over the Golan Heights. Israel later conducted airstrikes targeting the drone’s control the towns of Tal Tuqan and Surman in Eastern Idlib Province on February 9 and February vehicle at the T4 Airbase in Eastern Homs Province. Syrian Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (SAMS) 15, respectively. The TSK also reportedly scouted the Taftanaz Airbase north of Idlib City as engaged the returning aircraft and successfully shot down an Israeli F-16 over Northern Israel. The well as the Wadi Deif Military Base near Khan Sheikhoun in Southern Idlib Province. Turkey incident marked the first such combat loss for the Israeli Air Force since the 1982 Lebanon War. established a similar observation post at Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 5. Israel in response conducted airstrikes targeting at least a dozen targets near Damascus including The Russian Armed Forces later deployed a contingent of military police to the regime-held at least four military positions operated by Iran in Syria. town of Hadher opposite Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 14. 2 February 17 - 20: Pro-Regime Forces Set Qamishli 7 February 18: Ahrar Conditions for Major Offensive in Eastern a-Sham Merges with Key Ghouta: Pro-regime forces intensified a campaign 9 Islamist Group in Northern of airstrikes and artillery shelling targeting the 8 Syria: Salafi-Jihadist group Ahrar opposition-held Eastern Ghouta suburbs of Al-Hasakah a-Sham merged with Islamist group Damascus, killing at least 250 civilians. -

REGIONAL ANALYSIS SYRIA Received Little Or No Humanitarian Assistance in More Than 10 Months

currently estimated to be living in hard to reach or besieged areas, having REGIONAL ANALYSIS SYRIA received little or no humanitarian assistance in more than 10 months. 07 February 2014 Humanitarian conditions in Yarmouk camp continued to worsen with 70 reported deaths in the last 4 months due to the shortage of food and medical supplies. Local negotiations succeeded in facilitating limited amounts of humanitarian Part I – Syria assistance to besieged areas, including Yarmouk, Modamiyet Elsham and Content Part I Barzeh neighbourhoods in Damascus although the aid provided was deeply This Regional Analysis of the Syria conflict (RAS) is an update of the December RAS and seeks to Overview inadequate. How to use the RAS? bring together information from all sources in the The spread of polio remains a major concern. Since first confirmed in October region and provide holistic analysis of the overall Possible developments Syria crisis. In addition, this report highlights the Map - Latest developments 2013, a total of 93 polio cases have been reported; the most recent case in Al key humanitarian developments in 2013. While Key events 2013 Hasakeh in January. In January 2014 1.2 million children across Aleppo, Al Part I focuses on the situation within Syria, Part II Information gaps and data limitations Hasakeh, Ar-Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor, Hama, Idleb and Lattakia were vaccinated covers the impact of the crisis on neighbouring Operational constraints achieving an estimated 88% coverage. The overall health situation is one of the countries. More information on how to use this Humanitarian profile document can be found on page 2. -

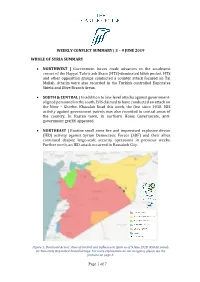

Weekly Conflict Summary | 3 – 9 June 2019

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 3 – 9 JUNE 2019 WHOLE OF SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST | Government forces made advances in the southwest corner of the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb pocket. HTS and other opposition groups conducted a counter attack focused on Tal Mallah. Attacks were also recorded in the Turkish-controlled Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch Areas. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | In addition to low-level attacks against government- aligned personnel in the south, ISIS claimed to have conducted an attack on the Nimr – Gherbet Khazalah Road this week, the first since 2018. ISIS activity against government patrols was also recorded in central areas of the country. In Rastan town, in northern Homs Governorate, anti- government graffiti appeared. • NORTHEAST | Routine small arms fire and improvised explosive device (IED) activity against Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and their allies continued despite large-scale security operations in previous weeks. Further north, an IED attack occurred in Hassakeh City. Figure 1: Dominant Actors’ Area of Control and Influence in Syria as of 9 June 2019. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. For more explanation on our mapping, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 7 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 3 – 9 JUNE 2019 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 This week, Government of Syria (GOS) forces made advances in the southwest corner of the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb enclave. On 3 June, GOS Tiger Forces captured al Qasabieyh town to the north of Kafr Nabuda, before turning west and taking Qurutiyah village a day later. Currently, fighting is concentrated around Qirouta village. However, late on 5 June, HTS and the Turkish-Backed National Liberation Front (NLF) launched a major counter offensive south of Kurnaz town after an IED detonated at a fortified government location. -

After the Revolution a Decade of Tunisian and North African Politics

After the Revolution A Decade of Tunisian and North African Politics The Monographs of ResetDOC Anderson, Benalla, Boughanmi, Ferrara, Grewal, Hamzawy, Hanau Santini, Laurence, Masmoudi, Özel, Torelli, Varvelli edited by Federica Zoja The Monographs of Reset DOC The Monographs of Reset DOC is an editorial series published by Reset Dialogues on Civilizations, an international association chaired by Giancarlo Bosetti. Reset DOC promotes dialogue, intercultural understanding, the rule of law and human rights in various contexts, through the creation and dissemination of the highest quality research in human sciences by bringing together, in conferences and seminars, networks of highly esteemed academics and promising young scholars from a wide variety of backgrounds, disciplines, institutions, nationalities, cultures, and religions. The Monographs of Reset DOC offer a broad range of analyses on topical political, social and cultural issues. The series includes articles published in Reset DOC’s online journal and original essays, as well as conferences and seminars proceedings. The Monographs of Reset DOC promote new insights on cultural pluralism and international affairs. After the Revolution A Decade of Tunisian and North African Politics Edited by Federica Zoja Drawn from the proceedings of the conference convened by Reset DOC An Arab Winter? The Tunisian Exception in Context on 14/15 December 2020 Contents The Monographs of ResetDOC 9 Foreword Soli Özel Publisher Reset-Dialogues on Civilizations 17 Introduction via Vincenzo Monti 15, 20123 Milan – Italy Federica Zoja ISBN 9788894186956 Part I Photocopies are allowed for personal use, provided that they do not exceed a maximum of 15% of the work and that due remuneration An Arab Winter? foreseen by art. -

Turkey's Strategic Reasoning Behind Operation Olive Branch

NO: 34 PERSPECTIVE JANUARY 2018 Turkey’s Strategic Reasoning behind Operation Olive Branch MURAT YEŞİLTAŞ • What is the strategic reasoning behind Turkey’s military operation against the PKK in the Afrin region? • What does Turkey’s game plan mean for the region? • What are the implications of Turkey’s military operation for the future of the Turkey-U.S.-Russia triangle? Following Operation Euphrates Shield (OES), Tur- has been designated as a terrorist organization by key added a new dimension to its ongoing military NATO, the EU and the U.S., the YPG controls 65% activity in Syria in order to curb the PKK’s influence of the Turkey-Syria border and uses its position to at- in northern Syria and to “de-territorialize” it in the tack Turkey. More importantly, the YPG is playing a medium term in the rest of the Syrian territory. With vital role in the PKK’s ongoing terrorist attacks inside the advent of the Afrin operation, Turkey’s military Turkey.1 It is also well-known that the YPG is tactical- activity has spread to a wider geographical area in the ly used by the PKK as an integral part of its irregular western bank of the Euphrates. The operation, which warfare strategy both in terms of manpower and mili- had been in the preparation phase for a long time, tary equipment in the fight against the Turkish Armed started on October 20 with the offensive phase, Forces in the southeastern part of Turkey.2 Therefore, shortly after President Erdoğan’s statement with first and foremost, Operation Olive Branch (OOB) is strong references to the UNSC’s decisions with re- an integral part of Turkey’s counter-terrorism strategy, gards to war on terror and the ‘self-defense’ element which Turkish security forces have adopted against in Article 51 of the UN Charter.