Anadromous Fish Survey Pohick and Accotink Creeks 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

Photo by King Montgomery. by Photo Table of Contents 7 Foreword 8 Fly Fishing Virginia 11 Flies to Use in Virginia 17 Top Virginia Fly Fishing Waters 19 Accotink Creek 21 Back Creek 25 Big Wilson Creek 29 Briery Creek Lake 33 Chesapeake Bay Islands Beasley. Beau by Photo 37 Conway River 41 Dragon Run 43 Gwynn Island 47 Holmes Run Beasley. Beau by Photo 51 Holston River, South Fork 53 Jackson River, Lower Section 59 Jackson River, Upper Section 63 James River, Lower Section 67 James River, Upper Section 71 Lake Brittle 75 Lynnhaven River, Bay, & Inlet 79 Maury River 4 Photo by Eric Evans. Eric by Photo 83 Mossy Creek 87 New River, Lower Section 91 New River, Upper Section 95 North Creek 97 Passage Creek 99 Piankatank River 101 Rapidan River, Lower Section Beasley. Beau by Photo 105 Rapidan River, Upper Section 109 Rappahannock River, Lower Section 113 Rappahannock River, Upper Section 117 Rivanna River 121 Rose River 125 Rudee Inlet 129 Shenandoah River, North Fork Photo by Beau Beasley. Beau by Photo 133 Shenandoah River, South Fork 137 South River 141 St. Mary’s River 145 Whitetop Laurel Creek Chris Newsome. by Photo 148 Private Waters 151 Resources 155 Conservation 156 Other No Nonsense Guides 158 Fly Fishing Knots 5 Arlington 81 66 Interstate South U.S. Highway River 95 State Highway 81 Other Roadway 64 64 Richmond Virginia Boat Launch 64 460 Fish Hatchery Roanoke Hampton 81 95 To Campground 77 58 Hermitage 254 To Grottoes To 340 Staunton ay rkw n Pa ema Hop 254 ver Ri 250 h ut So 340 340 1 Waynesboro To 2 Staunton 2 3 664 64 624 To Charlottesville 250 er iv R h ut 64 So 624 To 1 Constitution Park–Home of Charlottesville Virginia Fly Fishing Festival 2 Good Wading 3 Low water dam South River 136 South River outh River is one of the most underrated fisheries in the Old Dominion. -

Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Woodlawn Cultural Landscape Historic District Other names/site number: DHR File No.: 029-5181 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Bounded by Old Mill Rd, Mt Vernon Memorial Hwy, Fort Belvoir, and Dogue Creek City or town: Alexandria State: VA County: Fairfax Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: X ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional -

Pohick Creek Watershed Management Plan Are Included in This Section

Watershed Management Area Restoration Strategies 5.0 Watershed Management Area Restoration Strategies The Pohick Creek Watershed is divided into ten smaller watershed management areas (WMAs) based on terrain. Summaries of Pohick Creek’s ten WMAs are listed in the following WMA sections, including field reconnaissance findings, existing and future land use, stream conditions and stormwater infrastructure. For Fairfax County planning and management purposes the WMAs have been further subdivided into smaller subwatersheds. These areas, typically 100 – 300 acres, were used as the basic units for modeling and other evaluations. Each WMA was examined at the subwatershed level in order to capture as much data as possible. The subwatershed conditions were reviewed and problem areas were highlighted. Projects were proposed in problematic subwatersheds. The full Pohick Creek Draft Watershed Workbook, which contains detailed watershed characterizations, can be found in the Technical Appendices. Pohick Creek has four major named tributaries (see Map 3-1.1 in Chapter 3). In the northern portions of the watershed two main tributaries converge into Pohick Creek stream. The Rabbit Branch tributary begins in the highly developed areas of George Mason University and Fairfax City, while Sideburn Branch tributary begins in the highly developed area southwest of George Mason University. The confluence of these two headwater tributaries forms the Pohick Creek main stem. The Middle Run tributary drains Huntsman Lake and moderately-developed residential areas. The South Run tributary drains Burke Lake and Lake Mercer, as well as the low-density southwestern portion of the watershed. The restoration strategies proposed to be implemented within the next ten years (0 – 10-year plan) consist of 90 structural projects. -

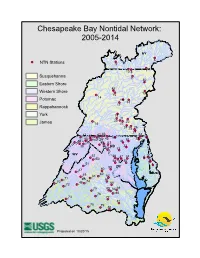

Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: 2005-2014

Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: 2005-2014 NY 6 NTN Stations 9 7 10 8 Susquehanna 11 82 Eastern Shore 83 Western Shore 12 15 14 Potomac 16 13 17 Rappahannock York 19 21 20 23 James 18 22 24 25 26 27 41 43 84 37 86 5 55 29 85 40 42 45 30 28 36 39 44 53 31 38 46 MD 32 54 33 WV 52 56 87 34 4 3 50 2 58 57 35 51 1 59 DC 47 60 62 DE 49 61 63 71 VA 67 70 48 74 68 72 75 65 64 69 76 66 73 77 81 78 79 80 Prepared on 10/20/15 Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: All Stations NTN Stations 91 NY 6 NTN New Stations 9 10 8 7 Susquehanna 11 82 Eastern Shore 83 12 Western Shore 92 15 16 Potomac 14 PA 13 Rappahannock 17 93 19 95 96 York 94 23 20 97 James 18 98 100 21 27 22 26 101 107 24 25 102 108 84 86 42 43 45 55 99 85 30 103 28 5 37 109 57 31 39 40 111 29 90 36 53 38 41 105 32 44 54 104 MD 106 WV 110 52 112 56 33 87 3 50 46 115 89 34 DC 4 51 2 59 58 114 47 60 35 1 DE 49 61 62 63 88 71 74 48 67 68 70 72 117 75 VA 64 69 116 76 65 66 73 77 81 78 79 80 Prepared on 10/20/15 Table 1. -

River Watch Spring 2010

The Newsletter of Potomac RiveRkeepeR, Inc. Volume 7, Issue 1, Winter 2010 495 HOT Lanes Construction Polluting In This Issue Accotink Creek Agricultural Pollution in W. Virginia page 2 s snow pummeled northern Virginia, APotomac Riverkeeper took action against a major polluter in Fairfax Stormwater Regulations Stalled County, VA. page 3 As you might know, a portion of the I- 495 High Occupancy Toll (“HOT”) Lanes From the Board construction site is severely damaging page 4 Accotink Creek, the Potomac River, and the Chesapeake Bay. Sediment pollution News in Brief is leaving the site and has entered page 5 Accotink Creek and its tributaries on numerous occasions. Potomac Riverkeeper’s 10th Anniversary Potomac Riverkeeper and two individuals page 6 sought to end this problem by notifying Fluor-Lane LLC, the HOT Lanes developers, of our intent to sue under the Clean Water Upcoming Events Act (CWA) if Fluor-Lane continues to violate page 7 Virginia law and allow the pollution to enter Accotink Creek. Coverage of our Mattawoman WWTP Permit action ran in The Washington Post. page 8 Flour-Lane has not stopped polluting despite numerous complaints from the public and inspections from state Polluted water is leaving the HOT Lanes Get the DIRT Out agencies. If Fluor-Lane does not stop the construction site and entering Accotink Creek. Photo by Kris Unger. As you just read, some developers allow polluted sludge pollution and comply with the law, legal to run into our rivers and streams, leaving taxpayers action may be one of the few remaining the stream. He also made site visits and with a hefty clean up bill. -

Belle Haven, Dogue Creek and Four Mile Run

1 Introduction to Watersheds A watershed is an area of land that drains all of its water to a specific lake or river. As rainwater and melting snow run downhill, they carry sediment and other materials into our streams, lakes, wetlands and groundwater. The boundary of a watershed is defined by the watershed divide, which is the ridge of highest elevation surrounding a given stream or network of streams. A drop of rainwater falling outside of this boundary will enter a different watershed and will flow to a different body of water. Figure 1-1: Diagram of a watershed Streams and rivers may flow through many different types of land use in their paths to the ocean. In the above illustration from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, water flows from agricultural lands to residential areas to industrial zones as it moves downstream. Each land use presents unique impacts and challenges on water quality. The size of a watershed can be subjective; it depends on the scale that is being considered. The image to the left depicts the extent of the Chesapeake Bay watershed, "the big picture" that is linked to our local concerns. This watershed covers 64,000 square miles and crosses into six states: New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, West Virginia, Maryland, Virginia and the District of Columbia. One of the watersheds that comprise the Chesapeake Bay watershed is the Potomac River watershed. Fairfax County, as shown on the map, occupies approximately 400 square miles of the Potomac River watershed. This area contains 30 smaller watersheds. Think of watersheds as being "nested" within each successively larger one. -

Corridor Analysis for the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail in Northern Virginia

Corridor Analysis For The Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail In Northern Virginia June 2011 Acknowledgements The Northern Virginia Regional Commission (NVRC) wishes to acknowledge the following individuals for their contributions to this report: Don Briggs, Superintendent of the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail for the National Park Service; Liz Cronauer, Fairfax County Park Authority; Mike DePue, Prince William Park Authority; Bill Ference, City of Leesburg Park Director; Yon Lambert, City of Alexandria Department of Transportation; Ursula Lemanski, Rivers, Trails and Conservation Assistance Program for the National Park Service; Mark Novak, Loudoun County Park Authority; Patti Pakkala, Prince William County Park Authority; Kate Rudacille, Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority; Jennifer Wampler, Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation; and Greg Weiler, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The report is an NVRC staff product, supported with funds provided through a cooperative agreement with the National Capital Region National Park Service. Any assessments, conclusions, or recommendations contained in this report represent the results of the NVRC staff’s technical investigation and do not represent policy positions of the Northern Virginia Regional Commission unless so stated in an adopted resolution of said Commission. The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the jurisdictions, the National Park Service, or any of its sub agencies. Funding for this report was through a cooperative agreement with The National Park Service Report prepared by: Debbie Spiliotopoulos, Senior Environmental Planner Northern Virginia Regional Commission with assistance from Samantha Kinzer, Environmental Planner The Northern Virginia Regional Commission 3060 Williams Drive, Suite 510 Fairfax, VA 22031 703.642.0700 www.novaregion.org Page 2 Northern Virginia Regional Commission As of May 2011 Chairman Hon. -

Board Agenda Item July 30, 2019 ACTION

Board Agenda Item July 30, 2019 ACTION - 8 Endorsement of Design Plans for the Richmond Highway Corridor Improvements Project from Jeff Todd Way to Sherwood Hall Lane (Lee and Mount Vernon Districts) ISSUE: Board endorsement of the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) Design Public Hearing plans for the 3.1-mile Richmond Highway Corridor Improvements Project between Jeff Todd Way/Mount Vernon Memorial Highway and Sherwood Hall Lane. The purpose of the project is to increase capacity, safety, and mobility for all users. Improvements include widening Richmond Highway from four to six lanes; reserving the median for the future Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system; replacing structures over Dogue Creek, Little Hunting Creek, and the North Fork of Dogue Creek; intersection improvements; sidewalks; and two-way cycle tracks on both sides of the road. RECOMMENDATION: The County Executive recommends that the Board endorse the design plans for the Richmond Highway Corridor Improvements project administered by VDOT as generally presented at the March 26, 2019, Design Public Hearing and authorize the Director of FCDOT to transmit the Board’s endorsement to VDOT (Attachment I). TIMING: The Board should take action on this matter on July 30, 2019, to allow VDOT to proceed with final design plans and enter the Right-of-Way (ROW) phase in late 2019 to keep the project on schedule. BACKGROUND: In 1994, the Virginia General Assembly directed VDOT to perform a centerline design study of the 27-mile Route 1 corridor between the Stafford County line and the Capital Beltway. There was a continuation of the Centerline Study in 1996 and 1998. -

Sediment TMDL Action Plan for Difficult Run and Accotink Creek Submittal to DEQ – May 1, 2020

Town of Vienna, Virginia Sediment TMDL Action Plan for Difficult Run and Accotink Creek Submittal to DEQ – May 1, 2020 Town of Vienna Department of Public Works 127 Center Street, South Vienna, Virginia 22180 Prepared with assistance by: Wood Environment & Infrastructure Solutions Chantilly, Virginia Prepared in Compliance with Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) Permit No. VAR040066 CERTIFICATION "I certify under penalty of law that this document and all attachments were prepared under my direction or supervision in accordance with a system designed to assure that qualified personnelproperly gather and evaluate the information submitted. Based on my inquiry ofthe person or persons who managethe system, or those persons directly responsible for gathering the information,the information submitted is, to the best ofmy knowledge and belief, true, accurate, and complete. I am awarethatthere are significant penalties for submitting false information, including the possibility of fine and imprisonment for knowingviolations." HK, own JYIWAGER 05fer [20 “Name # / Title Datf JS Town of Vienna, Virginia Sediment TMDL Action Plan for Difficult Run and Accotink Creek May 1, 2020 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Purpose ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Chesapeake Bay TMDL Action -

FACC Bulletin December, 2020

Bulletin of the Proceedings of the Friends of Accotink Creek Our meeting notes serve as bulletins of our activities, interests, and discussions, supplemented by your submissions. Friends of Accotink Creek Town Meeting – December 15, 2020 Next Meeting: January 19, 2021 (Third Tuesday of each month) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Present: Dave Lincoln, Julie Chang, Beverley Rivera, Philip Latasa. Avril Garland Edward Lee – Welcome Edward! Upcoming events · Salt Management Strategy Public Meeting January 21, 2021 · Stream Monitoring Lake Accotink Park March 13, 2021 · Anti-Wisteria Expedition April 5, 2021 Read the 2020 Friends of Accotink Creek Newsletter • Lake Accotink Park Master Plan: On December 10th there was a public meeting on the status of the dredge. Planning and surveys are underway now, with dredging expected to start in early 2023 and end by late 2025. According to Philip, it seems all options have closed other than a pipeline to Braddock Road, the only questions being the precise routing and the location of the dewatering facility at the terminus. Stormwater Planning has convened a smaller stakeholders group, including FACC, FLAP, Save Lake Accotink, and some civic associations. In the first such meeting, it seemed clear Howrey Field will not be an option since no one on the County side is willing to face the ‘flag vs. forest’ issues that were raised by Howrey defenders on our Facebook page. Howrey wasn’t likely to qualify anyway, but Philip asked would Flag vs. Forest – Not a fight anyone wants to pick anyone like to reach out to the defenders in search of common ground? Philip offered one more alternative that we might appeal to have considered: • A slower dredge could accomplish the same goal over a period of years, reducing truck traffic to tolerable levels. -

Chloride TMDL Action Plan for Accotink Creek May 1, 2021

Town of Vienna, Virginia Chloride TMDL Action Plan for Accotink Creek May 1, 2021 Town of Vienna Department of Public Works 127 Center Street, South Vienna, Virginia 22180 Prepared with assistance by: Wood Environment & Infrastructure Solutions Chantilly, Virginia Prepared in Compliance with Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) Permit No. VAR040066 Town of Vienna, Virginia Chloride TMDL Action Plan for Accotink Creek May 1, 2021 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Purpose ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Salt Management Strategy ........................................................................................................ 2 1.3 Permit Compliance Crosswalk .................................................................................................. 2 2. Chloride TMDL Action Plan ........................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Overview of the TMDL ............................................................................................................ 3 2.2 Waste Load Allocation .............................................................................................................. 5 2.3 Identification of Significant Sources of Chloride .................................................................... -

English Duplicates of Lost Virginia Records

T iPlCTP \jrIRG by Lot L I B RAHY OF THL UN IVER.SITY Of ILLINOIS 975.5 D4-5"e ILL. HJST. survey Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/englishduplicateOOdesc English Duplicates of Lost Virginia Records compiled by Louis des Cognets, Jr. © 1958, Louis des Cognets, Jr. P.O. Box 163 Princeton, New Jersey This book is dedicated to my grandmother ANNA RUSSELL des COGNETS in memory of the many years she spent writing two genealogies about her Virginia ancestors \ i FOREWORD This book was compiled from material found in the Public Record Office during the summer of 1957. Original reports sent to the Colonial Office from Virginia were first microfilmed, and then transcribed for publication. Some of the penmanship of the early part of the 18th Century was like copper plate, but some was very hard to decipher, and where the same name was often spelled in two different ways on the same page, the task was all the more difficult. May the various lists of pioneer Virginians contained herein aid both genealogists, students of colonial history, and those who make a study of the evolution of names. In this event a part of my debt to other abstracters and compilers will have been paid. Thanks are due the Staff at the Public Record Office for many heavy volumes carried to my desk, and for friendly assistance. Mrs. William Dabney Duke furnished valuable advice based upon her considerable experience in Virginia research. Mrs .Olive Sheridan being acquainted with old English names was especially suited to the secretarial duties she faithfully performed.