Experiential Art: Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Made in Melbourne!

Made in Melbourne! OCTOBER 2010 Enjoyed Nationally & Internationally! OCTOBER 2010 Issue 73 q comment: HAVING A FABOO TIME The era of renting skanky old costumes has past. Publisher & Editor Brett Hayhoe In recent months faboo has become affiliated with +61 (0) 422 632 690 an enormous costume company that has over 8000 [email protected] costumes. Over the past months they have been building a fantastic online store. They are in the process Editorial of integrating it with their U.S.A. based distributor. [email protected] Sales and Marketing Once they are online they will be able to offer an [email protected] amazing range of costumes. Design This is truly a unique Australian site dedicated to Uncle Brett Designs & Graphics Officially Licensed Marvel, DC Comics and Disney Contributing Writers Super Heroes, Super Villains, their comrades, minions Pete Dillon, Evan Davis, Alan Mayberry, and foe. They will be covering both super and lesser Tasman Anderson, Marc J Porter, Nathan known heroes and villains from movies and comics Miller, Barrie Mahoney, Brett Hayhoe, Chris from the 1950s to now. They will be able to offer Gregoriou, Ashley Hogan, Brian Mier Collector’s Edition Star Wars Darth Vader - formed Cover picture from the original Darth Vader moulds and a fully haired Jason Green by Avril Holderness-Roddam (head to toe) Wookiee Suit. Photographic Contributions Alan Mayberry (GH), Benjamin Ashe In addition, they have shipments arriving with the (Peel), Haans Siver (Neverwhere), collector’s batman in the next few weeks. Mathew Lynn (Q Drag), Avril Hold- erness-Roddam (Flamingos & fea- The store in Prahran is full of great costumes and ture) Twilight fans will be happy to know that their vampire Distribution friends will have a place in the Villainous Hero’s [email protected] section. -

CITY of F4DCTSC 1•2 AY Openinq of New Municipal Offices C Chambers by the Governor, Lord 1-Luntincifield VA/EVILER

CITY OF F4DCTSC 1•2 AY Openinq of New Municipal Offices c Chambers by the Governor, Lord 1-luntincifield VA/EVILER 201 — 1936 • EDWARD HANVIER, J.P., MAYOR OFFICIAL PROGRAM 1 HIS WORSHIP THE MAYOR, CR. E. HANMER =jnitaittcit.on • • • For many years the citizens of Footscray considered that the Muciicipal Buildings known as the Town Hall were not suitable. Indeed the structure had become unsafe to those who used or occupied it. The people had realised their City had made such progress that the retention of the old Town Hall was quite unjustifiable from any civic or other standpoint. This unanimity of opinion, however, entirely disappeared when consideration was given the type of new building and the site of the same. Many advocated that there should be a new Town Hall as well as Council Chamber and Municipal Offices, but these people differed in opinion whether the building should be at the existing site or at another. A large number of Citizens refused to admit the need of a public building, but agreed that new Council Chamber and Municipal Offices were needed. They also differed in opinion in respect of the site. This confusion of thought delayed action for some years. Eventually the Council decided in favor of new Council Chamber, Administrative Offices and Assembly Hall at the same site, the corner of Hyde and Napier Streets. These decisions were embodied in a certain loan proposition, which, when submitted to the people, in pursuance of the provisions of the Local Government Act, presented an opportunity to the ratepayers to veto the same. -

ATSS News Contents

Australasian Reach Tuberous Sclerosis Society OutNov 2012 Issue 96 Farewell to Sue Pinkerton P7 Knowledge Gained P 9 A Positive Outlook P13-14 www.atss.org.au ATSS News Contents Editorial ........................................................................................... 3 President’s Report ................................................................................... 4 Treasurer’s Report ................................................................................... 5 ATSS Supporter Renewals ............................................................................ 5 Membership Report ................................................................................. 6 Farewell to Sue Pinkerton ............................................................................ 7 Elizabeth Pinkerton Memorial Award ................................................................. 8 Knowledge Gained and Connections Made in Melbourne ................................................ 9 Committee Changes ................................................................................ 10 Sydney Seminar Day ................................................................................ 10 Perth 2013 ......................................................................................... 11 Hope for the Future ................................................................................ 12 A Positive Outlook ...............................................................................13-14 Still My Darling Julia .............................................................................. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,633,772 B2 Ford Et Al

USOO6633772B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,633,772 B2 Ford et al. (45) Date of Patent: Oct. 14, 2003 (54) FORMULATION AND MANIPULATION OF WO WO 96/00109 1/1996 DATABASES OF ANALYTE AND WO WO 97/02811 1/1997 ASSOCATED WALUES WO WO 99/58190 11/1999 WO WO OO/07013 A 2/2000 (75) Inventors: Russell Ford, Portola Valley, CA (US); WO WO OO/471.09 A 8/2000 Matthew J. Lesho, San Mateo, CA (US); Russell O. Potts, San Francisco, OTHER PUBLICATIONS CA (US); Michael J. Tierney, San Jose, CA (US); Charles W. Wei, Bolinder et al., “Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose in Type Fremont, CA (US) I Diabetic Patients: Comparison with Continuous Microdi alysis Measurements of Glucose in Subcutaneous Adipose (73) Assignee: Cygnus, Inc., Redwood City, CA (US) Tissue During Ordinary Life Conditions,” Diabetes Care (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 20(1):64–70 (1997). patent is extended or adjusted under 35 Ohkubo et al., “Intensive Insulin Therapy Prevents the U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. Progression of Diabetic Microvascular Complications in Japanese patients with Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes (21) Appl. No.: 09/927,583 Mellitus: a Randomized Prospective 6-year Study,” Diabe (22) Filed: Aug. 10, 2001 tes Research & Clinical Practice 28:103–117 (1995). (65) Prior Publication Data (List continued on next page.) US 2002/0045808 A1 Apr. 18, 2002 O O Primary Examiner Robert L. Nasser Related U.S. Application Data (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Barbara McClung; Gary (60) Provisional application No. -

MAAS Collection 28Feb12

MUSEUM OF APPLIED ARTS AND SCIENCES Compiled by Christina Sumner OAM, with input from curatorial colleagues, 2012 Collection Size: numbers Highlights reflect object records; actual number of individual items approx 400,000 SCIENCES AND TECHNOLOGY Agricultural 476 Farming and harvesting implements, machines, manuals and photographs related to the production of honey, Equipment wool, fruit, vegetables, grains, meat and dairy. McKay Sunshine stripper-harvester and reaper-binder, plus promotional models of the stripper-harvester and stump-jump plough. Animal Samples and 4507 Unprocessed and processed materials of animal origin, including skins, oils, furs, bone and horn. Birds, fish, Products mammals and reptiles are represented. Many examples demonstrate stages in the transformation of raw materials into economically valuable products. Bill Montgomery Wool Collection: more than 5000 wool samples provide a snapshot of results of innovative breeding programs carried out by Australian wool growers during the 1800s. By transforming the tiny short-woolled Spanish Merino into a large, long-woolled animal, Australians saved the world’s wool industry from being overtaken by cotton in the 1860s. It has been described as the single greatest re-engineering of an animal species in human history. Arms and Armour 1221 Broad range of edged weapons and firearms from different eras and cultures. Edged weapons: includes Japanese Samurai swords, Malay swords and daggers and Javanese ceremonial kris. Japanese Samurai suits of armour: Bronze cannon from Borneo: dolphin ornamentation, 18th century Correspondence of Evelyn Owen: consists of 55 letters concerning the development and production of the Owen sub-machine gun. Many early letters are congratulatory; most concern royalties paid to Owen and his application for tax exemption. -

This Here... “...Doesn’T Really Jump out and Eat My Face.” (G Mattingly)

ISSUE #45 This Here... “...doesn’t really jump out and eat my face.” (G Mattingly) It might be lazy to suggest that, as we get older, we find EGOTORIAL solace in familiarity and resentful of change or disruption, but quite honestly we mostly don’t deal immediately well CREATURE OF HABIT with challenges to our habits, including our ways of You might consider this a coda, corollary, whatever, to the thinking. Self-examination (a topic I’m going to return to in “Drudgery” Egotorial, since “habit” or perhaps more the future) is hard: it’s much easier to stay set in our ways accurately “routine” might be thought of as intrinsically and have that comforting security blanket of the familiar. dull. My work weekdays (Sunday - Thursday) would Justin Busch may well have already clocked that this here certainly qualify. Alarm goes off at 1am, I have two cups of Egotorial is going to segue into fanzine fanac, and so it is. coffee and perform the morning ablutions (triple-S1), and off to the yard Every continuing fanzine I’ve done (and at 2am or a tad after, put in my shift, get I’ll include the ill-fated single ish of home at 3pm-ish, get in the daily nichevo which was after all intended to be nosebag while watching an episode of continuing) has relied on a consistent something with Jen on the TV, then off format, if not a consistency of to bed no later than 5pm for, hopefully, a presentation (in the case of Arrows of decent 8 hours of kip before the next go. -

City of Melbourne Numismatic Collection Made in Melbourne

City of Melbourne Numismatic Collection By Darren Burgess The City of Melbourne has a unique collection of items that are important to the cultural and social history of the city. Many of these items are on permanent display in the form of artworks and architecture, while some come out from time to time in exhibitions, such as those held at the City Gallery, next to the Town Hall. Yet others still sit in cabinet drawers, behind locked doors, in a storage room down an anonymous laneway, where no-one sees them. This project is an attempt to shed light on some of these fascinating little-seen items. They not only tell a story of the City of Melbourne but also of some of the people that have helped shape it over the years. The project’s focus is numismatic items, a term that traditionally refers to coins, banknotes and medals. The collection has approximately 200 such items, ranging from examples of pre-decimal coinage through to elaborate exhibition medals. The majority of items described here fit into the coins and medals categories, but this project expands the definition to include badges held in the city’s Art and Heritage Collection. Badges were often manufactured by the same companies that produced coins and medals. They also frequently perform similar functions to medals, in that they are used to commemorate events, mark achievements or indicate membership of an organisation. Made in Melbourne Abundant skills in engraving and medal manufacture existed in Melbourne at the turn of the 19th century, as the following section, Selling Melbourne, shows; for example, Ernst Altmann, Stokes & Martin and the Melbourne branch of the Royal Mint. -

Greek Recorded Sound in Australia: “A Neglected Heritage”

GAUNTLETT.qxd 15/1/2001 2:34 ìì Page 25 Gauntlett, Stathis 2003. Greek Recorded Sound in Australia: “A Neglected Heritage”. In E. Close, M. Tsianikas and G. Frazis (Eds.) “Greek Research in Australia: Proceedings of the Fourth Biennial Conference of Greek Studies, Flinders University, September 2001”. Flinders University Department of Languages – Modern Greek: Adelaide, 25-46. Greek Recorded Sound in Australia A Neglected Heritage Stathis Gauntlett View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Flinders Academic Commons The subtitle connects this paper with a landmark publication in the bibli- ography of commercially recorded sound, the book Ethnic Recordings in America. A Neglected Heritage published by the American Folklife Center of the Library of Congress in Washington in 1982. This borrowing is in- tended to signal from the outset that parallels will be drawn in this paper be- tween Greek-Australian recorded sound and the now better documented Greek-American case. Contextualising the story of Greek recorded sound in Australia will also necessitate some narrative of developments in both the broader Australian and the metropolitan Greek record industry, as well as ex- tensive reference to the English Parent Company of the principal corpo- rate players in both Greece and Australia. This reflects the fact that sound recording has been a multinational industry virtually since its inception.1 My paper might have been better subtitled a neglected research topic, for this is the inevitable conclusion to be drawn from declared interests and publications to date.2 This is a pity, because Greek-Australian recorded 1 The company documents used in this paper are housed at the EMI Archives in Hayes, Middlesex, UK: the reference to country and date sources each document cited to an annual file for either Greece or Australia. -

Annual Report 09-2010

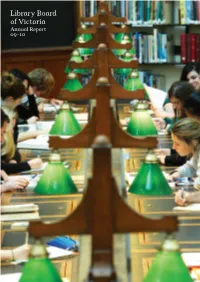

Library Board of Victoria Annual Report 09–10 Library Board of Victoria Annual Report 2009–10 1 Accountable Officer’s declaration In accordance with the Financial Management Act 1994, I am pleased to present the Library Board of Victoria’s Annual Report for the year ending 30 June 2010. John Cain President, Library Board of Victoria Library Board of Victoria Annual Report 2009–10 Published by the State Library of Victoria 328 Swanston Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000 Also published on slv.vic.gov.au © State Library of Victoria 2010 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government 328 Swanston Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000 Printed by Impact Digital Units 3–4, 306 Albert Street Brunswick 3056 2 Library Board of Victoria Annual Report 09/10 Contents 04 Vision and Values Financials 05 Highlights of the year 48 Auditor General’s report 08 Report of operations 50 Risk attestation 20 Financial summary 51 Library Board of 21 2009–10 Key Victoria letter Performance Indicators 53 Financial report for year 22 Service Agreement with ended 30 June 2010 the Minister for the Arts 58 Notes to the 24 Government Priority financial statements Areas 2009–10 26 Output framework 29 Library Board and Corporate Governance 36 Library Executive 37 Organisational structure 38 Reconciliation of executive officers 39 Financial management 40 Public sector values and employment principles 41 Statement of workforce data and merit and equity -

Made in Melbourne! Enjoyed Nationally!

APRIL 2009 Made in Melbourne! Enjoyed Nationally! APRIL 2009 q comment: GIRLS ON STAGE Issue 56 I don’t often use my column to promote gigs around Publisher & Editor town however on this occasion I thought what is Brett Hayhoe happening at the Opium Den and Priscillas was 0422 632 690 worthy of special attention. I went to the opening night [email protected] at the Den and it is simply one of those productions where having fun is the focus. The new show at Editorial Priscillas on a Wednesday night is again something [email protected] to behold - with my friend, the amazingly talented Sales and Marketing Katie Underwood. [email protected] Miss jumbo queen beauty pageant Australasia has Design Uncle Brett Designs & Graphics been fortunate enough to attract a steady stream of beautiful big bouncing bathing beauties. Portraying the Contributing Writers fuller-figured fancy-fetished gal as one with a positive Pete Dillon, Addam Stobbs, Brett Hayhoe, image to which other young hopefuls may achieve to Evan Davis, Ben Angel, Nathan Miller, George aspire, the contest is run in 3 parts. Round 1 is the Alexander, Ash Hogan parade and talent. Round 2 is titled bitchy shindigs Cover picture (a twisted take on drag charades). And finally, Round Vivien St James with the compliments of T J 3 - the eating competition (elimination round) Bateson Friday the 17th of this month will see the grandest Photographic Contributions Q Photos, T J Bateson & Mark of all grand finals with Melbourne’s own drag artiste Djilas (Vivien St James feature extraordinaire Mr Doug Lucas joining in the frivolities. -

Sydney Dance Company - a Study of a Connecting Thread with the Ballets Russes’

‘Sydney Dance Company - A study of a connecting thread with the Ballets Russes’ Peter Stell B.A. (Hons). The Australian Centre, School of Historical Studies, The University of Melbourne. A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Research May, 2009. i Declaration I declare that the work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original, except as acknowledged in the text, and that the material has not been submitted, either in whole or in part, for a degree at this or any other university. …………………………………………. Peter Stell ii Abstract This thesis addresses unexplored territory within a relatively new body of scholarship concerning the history of the Ballets Russes in Australia. Specifically, it explores the connection between the original Diaghilev Ballets Russes (1909- 1929) and the trajectories of influence of Russian ballets that visited Australia. The study’s hypothesis is that the Sydney Dance Company, under the artistic direction of Graeme Murphy between 1976 and 2007, and the creation in 1978 of Murphy’s first full-length work Poppy, best exemplifies in contemporary terms the influence in Australia of the Ballets Russes. Murphy was inspired to create Poppy from his reading of the prominent artistic collaborator of the Ballets Russes, Jean Cocteau. This thesis asserts that Poppy, and its demonstrable essential connection with the original Diaghilev epoch, was the principal driver of Murphy’s artistic leadership over fifty dance creations by himself and collaborative artists. This study sketches the origins of the Ballets Russes, the impact its launch made on dance in the West, and how it progressed through three distinguishable phases of influence. -

Catalogue Price: $33.00 Important Information for Buyers

AUSTR ALI AN B AN OO AUSTRALIAN K A UCTI ONS BOOK AUCTIONS Monday 29th May, 2017, at 6.30pm Monday 29th May 2017 AUSTRALIAN BOOK AUCTIONS ABA0086 AUSTRALIAN BOOK AUCTIONS THE COLLECTION OF MICHAEL AITKEN, Esq. The Port Phillip District of New South Wales, the Colony of Victoria, the Goldfields, and rare Ephemera To be sold by auction on Monday 29th May 2017 at 6.30 pm At Australian Book Auctions Gallery 909 High Street, Armadale, Victoria Telephone (+61) 03 9822 4522 Facsimile (+61) 03 9822 6873 Email [email protected] www.australianbookauctions.com On View At the Gallery, 909 High Street, Armadale, Victoria Friday 26th May from 10.00 am to 4.00 pm Saturday 27th May from 10.00 am to 4.00 pm Monday 29th May from 10.00 am to 4.00 pm Catalogue Price: $33.00 Important Information for Buyers Registration and Buyer’s numbers of 1.1% will be added to your invoice to cover bank The auction will be conducted using Buyer’s fees and charges. numbers. All prospective bidders are asked to register Condition of lots and collect a Buyer’s number before the sale. All lots are sold “as is”, in accordance with clauses 6a- Buyer’s premium f of the Conditions of Business, and Australian Book Please note that a Buyer’s premium of 19.8% Auctions makes no representation as to the condition of (inclusive of Goods and Services Tax) of the hammer any lot. Buyers should satisfy themselves as to the price on each lot is payable by the buyer.