William Meadowcroft, Edison's Personal Secretary, Conducted Interviews and Collected Reminiscences, Including Those of the Inventor Himself

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Elvis Presley for Ukulele Ebook

ELVIS PRESLEY FOR UKULELE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jim Beloff | 72 pages | 21 Mar 2011 | Hal Leonard Corporation | 9781423465560 | English | Milwaukee, United States Elvis Presley for Ukulele PDF Book Shipping Information. Dirty, Dirty Feeling. Swing Down Sweet Chariot. Essential Elements Ukulele. See details. Baby I Don't Care. Little Egypt. Stuck on You. Sheet music Poster. Talk About The Good Times. Starting Today. Skip to the beginning of the images gallery. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Sweet Angeline. This Is The Story. Paralyzed chr? That's All Right, Mama. He Touched Me. Playing For Keeps chr? It's Now or Never. A week, one-lick-per-day workout program for developing, improving, and maintaining baritone ukulele technique. Let It Be Me. It displays all chords in six tunings for the different sizes of the ukulele. Skip to the end of the images gallery. We will charge no extra to restring it. In The Garden. My Wish Came True Ukulele. You've been through Fast Track Ukulele 1 several times, and you're Five Sleepy Heads. I Got Lucky chr? Known Only To Him. It's Now Or Never. Blue Suede Shoes. All packages will be shipped with a signature requirement by default. Customer Questions. Beginner tabs. Notify me when this product is in stock. One Broken Heart For Sale chr? The accompanying CD contains 51 tracks of songs for demonstration and play along. Home 1 Books 2. Elvis Presley for Ukulele Writer Blue River chr 8 Blue Suede Shoes mix? Always on my mind. Amazing Grace. We're passionate about music, we're also highly experienced in all technical matters for the musical instruments we provide. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1950S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1950s Page 86 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1950 A Dream Is a Wish Choo’n Gum I Said my Pajamas Your Heart Makes / Teresa Brewer (and Put On My Pray’rs) Vals fra “Zampa” Tony Martin & Fran Warren Count Every Star Victor Silvester Ray Anthony I Wanna Be Loved Ain’t It Grand to Be Billy Eckstine Daddy’s Little Girl Bloomin’ Well Dead The Mills Brothers I’ll Never Be Free Lesley Sarony Kay Starr & Tennessee Daisy Bell Ernie Ford All My Love Katie Lawrence Percy Faith I’m Henery the Eighth, I Am Dear Hearts & Gentle People Any Old Iron Harry Champion Dinah Shore Harry Champion I’m Movin’ On Dearie Hank Snow Autumn Leaves Guy Lombardo (Les Feuilles Mortes) I’m Thinking Tonight Yves Montand Doing the Lambeth Walk of My Blue Eyes / Noel Gay Baldhead Chattanoogie John Byrd & His Don’t Dilly Dally on Shoe-Shine Boy Blues Jumpers the Way (My Old Man) Joe Loss (Professor Longhair) Marie Lloyd If I Knew You Were Comin’ Beloved, Be Faithful Down at the Old I’d Have Baked a Cake Russ Morgan Bull and Bush Eileen Barton Florrie Ford Beside the Seaside, If You were the Only Beside the Sea Enjoy Yourself (It’s Girl in the World Mark Sheridan Later Than You Think) George Robey Guy Lombardo Bewitched (bothered If You’ve Got the Money & bewildered) Foggy Mountain Breakdown (I’ve Got the Time) Doris Day Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs Lefty Frizzell Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo Frosty the Snowman It Isn’t Fair Jo Stafford & Gene Autry Sammy Kaye Gordon MacRae Goodnight, Irene It’s a Long Way Boiled Beef and Carrots Frank Sinatra to Tipperary -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Record Collectibles

Unique Record Collectibles 3-9 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 Made in gold vinyl with 7 inch Hound Dog picture sleeve embedded in disc. The idea was Elvis then and now. Records that were 20 years apart molded together. Extremely rare, one of a kind pressing! 4-2, 4-3 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 3-3 Elvis As Recorded at Madison 3-11 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 Made in black and blue vinyl. Side A has a Square Garden AFL1-4776 Made in blue vinyl with blue or gold labels. picture of Elvis from the Legendary Performer Made in clear vinyl. Side A has a picture Side A and B show various pictures of Elvis Vol. 3 Album. Side B has a picture of Elvis from of Elvis from the inner sleeve of the Aloha playing his guitar. It was nicknamed “Dancing the same album. Extremely limited number from Hawaii album. Side B has a picture Elvis” because Elvis appears to be dancing as of experimental pressings made. of Elvis from the inner sleeve of the same the record is spinning. Very limited number album. Very limited number of experimental of experimental pressings made. Experimental LP's Elvis 4-1 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 3-8 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 4-10, 4-11 Elvis Today AFL1-1039 Made in blue vinyl. Side A has dancing Elvis Made in gold and clear vinyl. Side A has Made in blue vinyl. Side A has an embedded pictures. Side B has a picture of Elvis. Very a picture of Elvis from the inner sleeve of bonus photo picture of Elvis. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Strictly Elvis Newsletter No.16.Pdf

NewsletterNewsletter No. No. 1165 Autumn Spring 2015 2016 Good Morning, We appreciate that not everyone has the You will, I’m sure, know that Joe Moscheo of Elvis’ Imperials time or inclination for social media but we died in January, just a month after he should have been in the really don’t want you to miss out so could I UK as Special Guest at a Concert that Strictly Elvis UK were ar- ask a big, big, favour? If you are on Email (or ranging in his honour. We cancelled the plans when it became if not then perhaps a friend or family mem- apparent that Joe’s condition had deteriorated to the point that ber is) then just email us your name to en- overseas travel would prove impossible. Joe wasn’t just an Elvis [email protected] and from that we’ll ‘contact’ or someone I did business with, but a genuine friend pick up your email address and in future, in and I miss him greatly. I wear his watch – the one he gave me addition to using Social Media, we’ll send outside Coventry Cathedral. He wanted to mark the occa- you details in an email. It was sad when Elvis sion, joking that he wouldn’t be offended if I preferred the one at The O2 finally closed its doors, but didn’t already on my wrist. I’ve worn his watch every day since. And we close it out in style with the Birthday always will. God Bless you Joe, we’ve lost a good ’un in you but Bash followed by our Last Night Farewell? I can imagine the welcome that was awaiting you in Heaven. -

Music List by Year

Song Title Artist Dance Step Year Approved 1,000 Lights Javier Colon Beach Shag/Swing 2012 10,000 Hours Dan + Shay & Justin Bieber Foxtrot Boxstep 2019 10,000 Hours Dan and Shay with Justin Bieber Fox Trot 2020 100% Real Love Crystal Waters Cha Cha 1994 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer Cha Cha /Foxtrot 1992 50 Ways to Say Goodbye Train Background 2012 7 Years Luke Graham Refreshments 2016 80's Mercedes Maren Morris Foxtrot Boxstep 2017 A Holly Jolly Christmas Alan Jackson Shag/Swing 2005 A Public Affair Jessica Simpson Cha Cha/Foxtrot 2006 A Sky Full of Stars Coldplay Foxtrot 2015 A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton Slow Foxtrot/Cha Cha 2002 A Year Without Rain Selena Gomez Swing/Shag 2011 Aaron’s Party Aaron Carter Slow Foxtrot 2000 Ace In The Hole George Strait Line Dance 1994 Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Foxtrot/Line Dance 1992 Ain’t Never Gonna Give You Up Paula Abdul Cha Cha 1996 Alibis Tracy Lawrence Waltz 1995 Alien Clones Brothers Band Cha Cha 2008 All 4 Love Color Me Badd Foxtrot/Cha Cha 1991 All About Soul Billy Joel Foxtrot/Cha Cha 1993 All for Love Byran Adams/Rod Stewart/Sting Slow/Listening 1993 All For One High School Musical 2 Cha Cha/Foxtrot 2007 All For You Sister Hazel Foxtrot 1991 All I Know Drake and Josh Listening 2008 All I Want Toad the Wet Sprocket Cha Cha /Foxtrot 1992 All I Want (Country) Tim McGraw Shag/Swing Line Dance 1995 All I Want For Christmas Mariah Carey Fast Swing 2010 All I Want for Christmas is You Mariah Carey Shag/Swing 2005 All I Want for Christmas is You Justin Bieber/Mariah Carey Beach Shag/Swing 2012 -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour. -

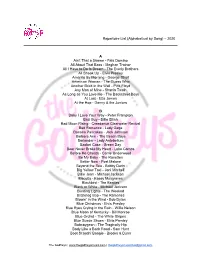

Repertoire List (Alphabetical by Song) – 2020 a Ain't

Repertoire List (Alphabetical by Song) – 2020 A Ain’t That a Shame - Fats Domino All About That Bass - Meghan Trainor All I Have to Do Is Dream - The Everly Brothers All Shook Up - Elvis Presley Amarillo By Morning - George Strait American Woman - The Guess Who Another Brick in the Wall - Pink Floyd Any Man of Mine - Shania Twain As Long as You Love Me - The Backstreet Boys At Last - Etta James At the Hop - Danny & the Juniors B Baby I Love Your Way - Peter Frampton Bad Guy - Billie Eilish Bad Moon Rising - Creedance Clearwater Revival Bad Romance - Lady Gaga Banana Pancakes - Jack Johnson Barbara Ann - The Beach Boys Bartender - Lady Antebellum Basket Case - Green Day Beer Never Broke My Heart - Luke Combs Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Be My Baby - The Ronettes Better Now - Post Malone Beyond the Sea - Bobby Darin Big Yellow Taxi - Joni Mitchell Billie Jean - Michael Jackson Biscuits - Kasey Musgraves Blackbird - The Beatles Black or White - Michael Jackson Blinding Lights - The Weeknd Blitzkrieg Bop - The Ramones Blowin’ in the Wind - Bob Dylan Blue Christmas - Elvis Presley Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain - Willie Nelson Blue Moon of Kentucky - Bill Monroe Blue Orchid - The White Stripes Blue Suede Shoes - Elvis Presley Bobcaygeon - The Tragically Hip Body Like a Back Road - Sam Hunt Boot Scootin’ Boogie - Brooks & Dunn The Godfreys | www.thegodfreysmusic.com | [email protected] Branded Man - Merle Haggard Breathin’ - Ariana Grande Bridge Over Troubled Water - Simon & Garfunkel Brown Eyed Girl - Van Morrison Building -

Elvis Mega Karaokepakke CDG

Elvis Mega Karaokepakke CDG Adam & Evil After Loving You Ain't That Lovin' You Baby All I Needed Was Rain All Shook Up All Shook Up (Live) All That I Am Almost Almost Always True Almost In Love Always On My Mind Am I Ready Amazing Grace America The Beautiful American Trilogy And I Love You So And The Grass Won't Pay No Mind Angel Any Day Now Any Place In Paradise Any Way You Want Me Anyone Could Fall In Love With You Anything That's Part Of You Are You Lonesome Tonight Are You Lonesome Tonight Are You Sincere As Long As I Have You Ask Me Elvis Mega Karaokepakke CDG Baby I Don't Care Baby Let's Play House Beach Boy Blues Beyond The Bend Big Boots Big Boss Man Big Hunk O' Love, A (Live) Aloha Concert Big Love, Big Heartache Bitter They Are, Harder They Fall Blue Christmas Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain Blue Hawaii Blue Moon Blue Suede Shoes Blue Suede Shoes Blueberry Hill Blueberry Hill/I Can't Stop Loving (Medley) Bosom Of Abraham Bossa Nova Baby Boy Like Me, A Girl Like You, A Bridge Over Troubled Water (Live) Bringin' It Back Burning Love (Live) Aloha Concert By & By Can't Help Falling In Love Change Of Habit Charro Cindy, Cindy Clean Up Your Own Back Yard C'mon Everybody Elvis Mega Karaokepakke CDG Crawfish Cross My Heart, Hope To Die Crying In The Chapel Danny Boy Devil In Disguise Didja Ever Dirty Dirty Feeling Dixieland Rock Do Not Disturb Do You Know Who I Am Doin' The Best I Can Don't Don't Ask Me Why Don't Be Cruel Don't Cry Daddy Don't Leave Me Now Don't Think Twice Don'tcha Think It's Time Down By The Riverside/When The Saints