National Forests on the Edge D E V E L O P M E N T Pressures on a M E R I C A’S Nat I O N a L Forests and Grasslands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tipped Over the Edge

Tipped Over The edge Gender Inequity in the Restaurant Industry BY THE RESTAURANT OPPORTUNITIES CENTERS UNITED AND FAMILY VALUES @ WORK HERvotes COALITION INSTITUTE FOR WOMEN’S POLICY RESEARCH MOMSRISING NATIONAL COALITION ON BLACK CIVIC PARTICIPATION’S BLACK WOMEN’S ROUNDTABLE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR RESEARCH ON WOMEN NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN Foundation NATIONAL PARTNERSHIP FOR WOMEN & FAMILIES NATIONAL WOMEN’S LAW CENTER WIDER OPPORTUNITIES FOR WOMEN February 13, 2012 WOMEN OF COLOR POLICY NETWORK, NYU WAGNER 9TO5, National Association OF WORKING WOMEN RESEARCH SUPPORT The Ford Foundation The Moriah Fund The Open Society Foundations The Rockefeller Foundation February 13, 2012 Tipped Over The edge Gender Inequity in the Restaurant Industry AND FAMILY VALUES @ WORK HERvotes COALITION INSTITUTE FOR WOMEN’S POLICY RESEARCH MOMSRISING NATIONAL COALITION ON BLACK CIVIC PARTICIPATION’S BLACK WOMEN’S ROUNDTABLE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR RESEARCH ON WOMEN NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN Foundation NATIONAL PARTNERSHIP FOR WOMEN & FAMILIES NATIONAL WOMEN’S LAW CENTER WIDER OPPORTUNITIES FOR WOMEN WOMEN OF COLOR POLICY NETWORK, NYU WAGNER 9TO5, National Association OF WORKING WOMEN RESEARCH SUPPORT The Ford Foundation The Moriah Fund The Open Society Foundations The Rockefeller Foundation February 13, 2012 Tipped Over The edge Gender Inequity in the Restaurant Industry BY THE RESTAURANT OPPORTUNITIES CENTERS UNITED AND FAMILY VALUES @ WORK HERvotes COALITION INSTITUTE FOR WOMEN’S POLICY RESEARCH MOMSRISING NATIONAL COALITION ON BLACK CIVIC PARTICIPATION’S -

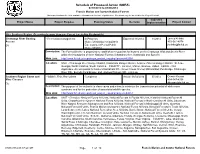

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2014 to 09/30/2014 Francis Marion and Sumter National Forests This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact R8 - Southern Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Chattooga River Boating - Recreation management In Progress: Expected:11/2014 11/2014 James Knibbs Access Notice of Initiation 07/24/2013 803-561-4078 EA Est. Comment Period Public [email protected] Notice 07/2014 Description: The Forest Service is proposing to establish access points for boaters on the Chattooga Wild and Scenic River within the boundaries of three National Forests (Chattahoochee, Nantahala and Sumter). Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/nepa/nepa_project_exp.php?project=42568 Location: UNIT - Chattooga River Ranger District, Nantahala Ranger District, Andrew Pickens Ranger District. STATE - Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina. COUNTY - Jackson, Macon, Oconee, Rabun. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Access points for boaters:Nantahala RD - Green Creek; Norton Mill and Bull Pen Bridge; Chattooga River RD - Burrells Ford Bridge; and, Andrew Pickens RD - Lick Log. Southern Region Caves and - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants Completed Actual: 06/02/2014 07/2014 Dennis Krusac Mine Closures 404-347-4338 CE [email protected] Description: The purpose of the action is to close caves and mines to minimize the transmission potential of white nose -

SONG ACTIVITY – Beautiful Day by U2

SONG ACTIVITY – Beautiful Day by U2 Name: Group: Date: / / 1. Work in small groups. Read the definition for the word “resilient”. Discuss the questions. resilient /rɪˈzɪliənt/ adj 1 able to become strong, healthy or successful again after something bad happens. 2 able to return to an original shape after being pulled, stretched, pressed, bent, etc. Adapted from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/resilient a. Can you think of a situation in your life when you or a person you know were resilient? Talk about it. b. What can teenagers do to develop resilience? c. What do you usually do when you are having a difficult day? 2. Work with a partner. You are going to listen to the song Beautiful Day, by U2. The words in the cloud are in the lyrics of the song. How do you associate them with a beautiful day? Discuss your ideas and take notes in the lines below. ________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________ 3. Now listen to the song. Were the words in Activity 2 associated to the idea of a beautiful day in the way you imagined? SONG ACTIVITY – Beautiful Day by U2 4. Listen to the song again. Check (✓) the alternative that best explains the lines in italics, in the context of the song. a. The heart is a bloom / Shoots up through the stony ground. [ ] Love is resilient and can overcome all difficulties. [ ] Love is blind to all problems and difficulties. b. The traffic is stuck / And you’re not moving anywhere. [ ] Traffic jams can ruin even the most beautiful day. -

TCWP Newsletter No

TENNESSEE CITIZENS FOR WILDERNESS PLP..NNING Newsletter No. 53. February 5, 1973 * concentrate issues x:e.qu::re We depart frOom our usual Newsletter format to on two that your attenticn -- the Bj.g South F k (item 2) and Easterri; Wilde.rness ( ite.m 3) We or Q s t hope this limited a s ignmEnt will encourage many of you to ACT" In a.ddi ion, note the announcement of our next meetingn 1.. HEAD OF WATER POLLUTION AGENCY TO ADDRE3S............ TCWP ---�----------------..,...,. ----�� Time � Weduesda.y" Febru.al·Y 28 i 8: 00 p. me Place: Oak Ridge Civic Center. S ocial Room) Oak Ridge Turnpike (2 blocks east of Highway 1162 intersectic·n) Speaker: Mr. So Lea:ry Jones:� Executive Secre.tary. Tenness�e Water Qu.ality Contt"cl Board about Mrn Jones will talk the workings of the Tennessee Water Quality Control Act i pollu· of 1971 ( c ons dere.d "by ma,ny to be a mo del law), and about ne'W" f€;deral water tion legislationo Many of us are particularly c.oncerned about stripmine discha.rgtas, and Mre Jones has prorolsed to devote time to this tOpiC0 BRING YOUR INTERESTED FRIENDS � 20 BIG SOUTH FORK NATIO�AL RIVER & RECREATIOli AREA .NEEDS SUFPORT On February l� the Senate passed by a vote of 67 :14 the Omnibus Rivers & Harbo1.:'s Act, Section 61 of which creates the 125.000-acre Big S. Fork Natio�al River and Recreation Areao Senator Baker's office cooperated c1o€'ely with cOI ..servation13ts Fork Prese:tvation into of the Big S () Coalition to write the bl11 Sfi:1cingent measun::s, for protecting wilderness of ths g orge s of all streams in the project area� Amend� ments added on the floG'r) at Sen . -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

Extending the Enterprise to the Edge Your Guide to Converging Operational and Information Technology

Extending the Enterprise to the Edge Your Guide to Converging Operational and Information Technology Traditionally, agencies have approached information technology as a separate discipline from operational technology, which includes data acquisition systems, control systems, industrial-class networks, and a wide variety of internet-connected devices that operate far beyond the walls of the data center. However, it is increasingly clear that the data gathered at the edge of operations can provide in- sights that agencies can use to improve the efficiency of their operations and deliver new services to support the mission. The key? Converging OT capabilities with enterprise-class IT systems in single box and deploying them at the edge. GovLoop, Affigent and Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE) collaborated on this worksheet to help you take advantage of this new wave of edge computing. Three Ways to Leverage OT-IT Convergence The benefits of converging OT and IT systems fall into three main categories: Physical systems Software and data Process convergence convergence convergence IT systems (compute, storage, Enterprise IT applications IT and OT teams agree to collaborate management, and security) collaborating with OT applications on end-to-end workflows and integrate in the same system chassis are applied to both traditional dataflows. with OT systems (data acquisition enterprise data and data derived systems, control systems, and at the edge. industrial networks). Leveraging Data at the Edge: A Framework By integrating OT and IT systems, agencies can create a flow of data from the enterprise out to the edge. By integrating this data, agencies can see greater insights into their operations and services. -

News Release

Cherokee National Forest 2800 Ocoee Street N. Cleveland, TN 37312 Web: http://fs.usda.gov/cherokee News Release Media Contact: (423) 476-9729 Terry McDonald Wilderness Closure CLEVELAND, TENN (November 12, 2016) – The U.S. Forest Service has implemented a closure for the entire Citico Creek Wilderness and the portion of the Joyce Kilmer-Slickrock Wilderness located in the Cherokee National Forest (Tennessee). This closure has been put in place for public safety due to wild fire activity in the Joyce Kilmer- Slickrock Wilderness in North Carolina. Beginning November 12, 2016, the following restrictions are in place for the Citico Creek Wilderness and the Joyce Kilmer-Slickrock Wilderness within the Cherokee National Forest until further notice: o Closure Pursuant to 36 CFR 261.52(e) – Going into or being upon any area of the Citico Creek Wilderness and Joyce Kilmer-Slickrock Wilderness within the Cherokee National Forest. Cherokee National Forest Supervisor, JaSal Morris said, “The closure of these wilderness areas was necessary for public safety. There is a possibility of the Maple Springs Fire in the Joyce Kilmer-Slickrock Wilderness in North Carolina moving into the Cherokee National Forest. We are closing this area to protect national forest visitors, who may be planning to visit the Citico Creek Wilderness and Joyce Kilmer-Slickrock Wilderness in the Cherokee National Forest, in case the fire moves into that area.” National Forest visitors are asked to obey all state and federal fire related laws and regulations. If you see smoke or suspicious activity contact local fire or law enforcement authorities immediately! -USDA- USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer and lender. -

Exhibit Designs for Girls' Engagement a Guide to the EDGE Design Attributes

Exhibit Designs for Girls’ Engagement A Guide to the EDGE Design Attributes EDGE visitor research Toni Dancstep (née Dancu) and Lisa Sindorf & evaluation This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1323806. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. How to cite: Dancstep (née Dancu), T. & Sindorf, L. (2016). Exhibit Designs for Girls’ Engagement: A Guide to the EDGE Design Attributes. San Francisco: Exploratorium. 2 EXHIBIT DESIGNS FOR GIRLS’ ENGAGEMENT Table of Contents 4–7 Introduction 8 –27 The EDGE Design Attributes 28 –41 Case Studies 42 –57 Appendix A: Assessing Exhibits 58 –61 Appendix B: Tested Design Attributes 62–65 References 66 –67 Acknowledgments EXHIBIT DESIGNS FOR GIRLS’ ENGAGEMENT | Table of Contents 3 Introduction 4 EXHIBIT DESIGNS FOR GIRLS’ ENGAGEMENT | Introduction As a child, Alice’s family encouraged her to Unfortunately, science museums aren’t always engage with science. But her visits to science working as well for girls as for boys, and many museums were less than positive. She remem- girls’ experiences may be similar to Alice’s. bers, “I would stand there, trying to figure out Some research has shown that girls visit what was so interesting, and usually fail at science museums less frequently than boys.4 doing so” and “I thought that I had to be able And once inside, girls often have different ex- to ‘figure out’ each exhibit to be ‘using the periences at exhibits than boys. -

U2 3D Talent: Bono, the Edge, Larry Mullen, Adam Clayton. Directors

U2 3D Talent: Bono, The Edge, Larry Mullen, Adam Clayton. Directors: Mark Pellington and Catherine Owens Duration: 85 minutes Classification: G We rate it: 3 and a half stars. There’s no denying that Irish rock band U2 are probably still the biggest live musical act in the world, even after twenty-odd years of touring. Aside from maybe the great outdoor extravaganzas mounted during the 1970s and 80s by Pink Floyd, U2’s live gigs are renowned as dazzling, cutting-edge spectacles, as politically and ideologically provocative as they are musically engaging. Bono, the acknowledged master of making fame itself humanely useful, still struts his stuff as if he’s a 25-year- old, and the band that supports him is as skilled as rock bands get. To see this chart- topping foursome filmed playing before staggeringly large crowds in state-of-the-art digital 3D and surround sound is, admittedly, quite a spectacle. The peculiar thing, however, about sitting in a cinema and watching U2 3D is that throughout the experience, stunning as it is, one can’t help but reflect upon the fact that one is sitting in a darkened room watching film of a band playing live in front of crowds of a hundred thousand people. There’s something decidedly strange about sitting passively and observing (through the suitably nerdy polarising 3D glasses) this massive rock show, whose actual filmed audiences just don’t stop screaming and waving for a second. As one ruminatively chews one’s popcorn and sips one’s soft- drink, one can’t help but feel faintly left out, to say the least. -

Notations Spring 2011

The ASCAP Foundation Making music grow since 1975 www.ascapfoundation.org Notations Spring 2011 Tony Bennett & Susan Benedetto Honored at ASCAP Foundation Awards The ASCAP Foundation held its 15th Annual Awards Ceremony at the Allen Room, Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center, in New York City on December 8, 2010. Hosted by ASCAP Foundation President, Paul Williams, the event honored vocal legend Tony Bennett and his wife, Susan Benedetto, with The ASCAP Foundation Champion Award in recognition of their unique and significant efforts in arts education. ASCAP Foundation Champion Award recipients Susan Benedetto (l) & Tony Bennett with Mary Rodgers (2nd from left), Mary Ellin A wide variety of ASCAP Foundation Scholarship Barrett (2nd from right), and ASCAP Foundation President Paul and Award recipients were also honored at the Williams (r). event, which included special performances by some of the honorees. For more details and photos of the event, please see our website. Bart Howard provides a Musical Gift The ASCAP Foundation is pleased to announce that composer, lyricist, pianist and ASCAP member Bart Howard (1915-2004) named The ASCAP Foundation as a major beneficiary of all royalties and copyrights from his musical compositions. In line with this generous bequest, The ASCAP Foundation has established programs designed to ensure the preservation of Bart Howard’s name and legacy. These efforts include: Songwriters: The Next Generation, presented by The ASCAP Foundation and made possible by the Bart Howard Estate which showcases the work of emerging songwriters and composers who perform on the Kennedy Center’s Millennium Stage. The ASCAP Foundation Bart Howard Songwriting Scholarship at Berklee College recog- nizes talent, professionalism, musical ability and career potential in songwriting. -

Cherokee National Forest

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Cherokee National Forest https://www.fs.usda.gov/cherokee/ CHEROKEE NATIONAL FOREST Following are the developed recreation site opening dates by Ranger District. Projected opening dates may vary depending on circumstances, and it may be necessary to not open or to close areas if conditions change. WATAUGA RANGER DISTRICT: 423-735-1500 Recreation Site Dates Open Holston Mountain Area Little Oak Campground*: Hemlock Loop June 1 – Oct 12 Poplar Loop June 1 – Oct 12 Big Oak Loop June 1 – Oct 12 Lone Pine Loop June 1 – Oct 12 Boat Ramp June 1 – Nov 16 Primitive Camping Only (no flush toilets) Big Oct 12 – Nov 16 Oak and Hemlock Loops ONLY Jacobs Creek Campground June 1 – Oct 12 Jacobs Creek Day Use Area June 1 – Oct 12 Iron Mountains Backbone Rock Recreation Area: Day use area (Pavilions*) May 15 – Nov 23 Backbone Rock Campground* June 1 - Oct 12 Watauga Lake Area Cardens Bluff Campground* June 1 - Oct 12 Dennis Cove Campground* June 1 - Oct 12 Shook Branch Swim Area May 15 – Sept 14 Watauga Point Recreation Area* May 15 – Oct 12 Roan Highlands Carvers Gap Trailhead (Vault Toilet) May 15 – Nov 23 Unaka Mountains Laurels Picnic Area (Pavilions*) May 15 – Oct 12 Shooting Ranges Pond Mountain and Jacobs Creek May 15 *Indicates some sites can be reserved: recreation.gov -More- Forest Service May 15, 2020 United States Department of Agriculture UNAKA RANGER DISTRICT: 423-638-4109 Recreation Site Dates Open Unaka Mountains Buffalo Mtn. ATV Trail May 15 – Jan 4, 2021 Limestone Cove Day Use Area* -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 10/01/2013 to 12/31/2013 National Forests In North Carolina This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact R8 - Southern Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Chattooga River Boating - Recreation management In Progress: Expected:03/2014 04/2014 James Knibbs Access Notice of Initiation 07/24/2013 803-561-4078 EA Est. Comment Period Public [email protected] *NEW LISTING* Notice 01/2014 Description: The Forest Service is proposing to establish access points for boaters on the Chattooga Wild and Scenic River within the boundaries of three National Forests (Chattahoochee, Nantahala and Sumter). Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/nepa/nepa_project_exp.php?project=42568 Location: UNIT - Chattooga River Ranger District, Nantahala Ranger District, Andrew Pickens Ranger District. STATE - Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina. COUNTY - Jackson, Macon, Oconee, Rabun. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Access points for boaters:Nantahala RD - Green Creek; Norton Mill and Bull Pen Bridge; Chattooga River RD - Burrells Ford Bridge; and, Andrew Pickens RD - Lick Log. Limits of Stay at Appalachian - Recreation management In Progress: Expected:10/2013 10/2013 Michelle Mitchell National Scenic Trail Shelters Comment Period Public Notice 404-347-1749 and Designated Campsites 08/16/2013 [email protected]. EA Est. Objection Period Legal us Notice 09/2013 Description: The Southern Region of the Forest Service is proposing to change its limits of stay at shelters and designated dispersed campsites along the Appalachian National Scenic Trail on several forests of the Southern Region.