Canteloube's Chants D'auvergne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Debussy's Pelléas Et Mélisande

Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande - A discographical survey by Ralph Moore Pelléas et Mélisande is a strange, haunting work, typical of the Symbolist movement in that it hints at truths, desires and aspirations just out of reach, yet allied to a longing for transcendence is a tragic, self-destructive element whereby everybody suffers and comes to grief or, as in the case of the lovers, even dies - yet frequent references to fate and Arkel’s ascribing that doleful outcome to ineluctable destiny, rather than human weakness or failing, suggest that they are drawn, powerless, to destruction like moths to the flame. The central enigma of Mélisande’s origin and identity is never revealed; that riddle is reflected in the wispy, amorphous property of the music itself, just as the text, adapted from Maeterlinck’s play, is vague and allusive, rarely open or direct in its expression of the characters’ velleities. The opera was highly innovative and controversial, a gateway to a new style of modern music which discarded and re-invented operatic conventions in a manner which is still arresting and, for some, still unapproachable. It is a work full of light and shade, sunlit clearings in gloomy forest, foetid dungeons and sea-breezes skimming the battlements, sparkling fountains, sunsets and brooding storms - all vividly depicted in the score. Any francophone Francophile will delight in the nuances of the parlando text. There is no ensemble or choral element beyond the brief sailors’ “Hoé! Hisse hoé!” offstage and only once do voices briefly intertwine, at the climax of the lovers' final duet. -

KING FM SEATTLE OPERA CHANNEL Featured Full-Length Operas

KING FM SEATTLE OPERA CHANNEL Featured Full-Length Operas GEORGES BIZET EMI 63633 Carmen Maria Stuarda Paris Opera National Theatre Orchestra; René Bologna Community Theater Orchestra and Duclos Chorus; Jean Pesneaud Childrens Chorus Chorus Georges Prêtre, conductor Richard Bonynge, conductor Maria Callas as Carmen (soprano) Joan Sutherland as Maria Stuarda (soprano) Nicolai Gedda as Don José (tenor) Luciano Pavarotti as Roberto the Earl of Andréa Guiot as Micaëla (soprano) Leicester (tenor) Robert Massard as Escamillo (baritone) Roger Soyer as Giorgio Tolbot (bass) James Morris as Guglielmo Cecil (baritone) EMI 54368 Margreta Elkins as Anna Kennedy (mezzo- GAETANO DONIZETTI soprano) Huguette Tourangeau as Queen Elizabeth Anna Bolena (soprano) London Symphony Orchestra; John Alldis Choir Julius Rudel, conductor DECCA 425 410 Beverly Sills as Anne Boleyn (soprano) Roberto Devereux Paul Plishka as Henry VIII (bass) Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Ambrosian Shirley Verrett as Jane Seymour (mezzo- Opera Chorus soprano) Charles Mackerras, conductor Robert Lloyd as Lord Rochefort (bass) Beverly Sills as Queen Elizabeth (soprano) Stuart Burrows as Lord Percy (tenor) Robert Ilosfalvy as roberto Devereux, the Earl of Patricia Kern as Smeaton (contralto) Essex (tenor) Robert Tear as Harvey (tenor) Peter Glossop as the Duke of Nottingham BRILLIANT 93924 (baritone) Beverly Wolff as Sara, the Duchess of Lucia di Lammermoor Nottingham (mezzo-soprano) RIAS Symphony Orchestra and Chorus of La Scala Theater Milan DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 465 964 Herbert von -

Bach and BACH

Bach and B-A-C-H Works by Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, Johann Sebastian Bach, Robert Schumann and Jan Esra Kuhl INTERNATIONAL BACH COMPETITION 2012 WINNER IN THE ORGAN CATEGORY Johannes Lang, Organ Bach and B-A-C-H Johannes Lang, Organ Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Praeludium in C, BWV 566 01 . (11'17) Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562–1621) Fantasia à 4, SwWV 273 02 . (12'59) Johann Sebastian Bach From “Art of the Fugue”, BWV 1080 03 Contrapunctus 14 . (10'10) Robert Schumann (1810–1856) From “Six Fugues on B.A.C.H., Op. 60” 04 2 . Vivace (Lebhaft) . (06'10) Johann Sebastian Bach Organ Sonata No. 6 in G major, BWV 530 05 Vivace . (04'08) 06 Lento . (10'11) 07 Allegro . (03'44) Jan Esra Kuhl (*1988) Variations on B-A-C-H (2013/2014) 08 . (06'25) World premiere recording Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata, Adagio and Fugue in C major, BWV 564 09 Toccata . (06'01) 10 Adagio . (05'07) 11 Fuge . (04'49) Total Time . (81'08) Deutsche Stiftung Musikleben | Supporting Aspiring Young Musicians Deutsche Stiftung Musikleben has been generously providing support to aspiring young mu- sicians in Germany since 1962 . The foundation provides long-term, personalized assistance to the current group of 300 scholarship recipients aged 12 to 30 . Jointly established with the German federal government, the Deutscher Musikinstru- mentenfonds provides promising young concert artists with string instruments of the highest quality, which are awarded each year as part of a demanding music competition . The foundation’s Foyer Junger Künstler concert series gives the foundation’s “rising stars” many different opportunities to show off their abilities. -

Composition Catalog

1 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 New York Content & Review Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. Marie Carter Table of Contents 229 West 28th St, 11th Floor Trudy Chan New York, NY 10001 Patrick Gullo 2 A Welcoming USA Steven Lankenau +1 (212) 358-5300 4 Introduction (English) [email protected] Introduction 8 Introduction (Español) www.boosey.com Carol J. Oja 11 Introduction (Deutsch) The Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc. Translations 14 A Leonard Bernstein Timeline 121 West 27th St, Suite 1104 Straker Translations New York, NY 10001 Jens Luckwaldt 16 Orchestras Conducted by Bernstein USA Dr. Kerstin Schüssler-Bach 18 Abbreviations +1 (212) 315-0640 Sebastián Zubieta [email protected] 21 Works www.leonardbernstein.com Art Direction & Design 22 Stage Kristin Spix Design 36 Ballet London Iris A. Brown Design Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited 36 Full Orchestra Aldwych House Printing & Packaging 38 Solo Instrument(s) & Orchestra 71-91 Aldwych UNIMAC Graphics London, WC2B 4HN 40 Voice(s) & Orchestra UK Cover Photograph 42 Ensemble & Chamber without Voice(s) +44 (20) 7054 7200 Alfred Eisenstaedt [email protected] 43 Ensemble & Chamber with Voice(s) www.boosey.com Special thanks to The Leonard Bernstein 45 Chorus & Orchestra Office, The Craig Urquhart Office, and the Berlin Library of Congress 46 Piano(s) Boosey & Hawkes • Bote & Bock GmbH 46 Band Lützowufer 26 The “g-clef in letter B” logo is a trademark of 47 Songs in a Theatrical Style 10787 Berlin Amberson Holdings LLC. Deutschland 47 Songs Written for Shows +49 (30) 2500 13-0 2015 & © Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. 48 Vocal [email protected] www.boosey.de 48 Choral 49 Instrumental 50 Chronological List of Compositions 52 CD Track Listing LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 2 3 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 A Welcoming Leonard Bernstein’s essential approach to music was one of celebration; it was about making the most of all that was beautiful in sound. -

The Nonlinear Physics of Musical Instruments

Rep. Prog. Phys. 62 (1999) 723–764. Printed in the UK PII: S0034-4885(99)65724-4 The nonlinear physics of musical instruments N H Fletcher Research School of Physical Sciences and Engineering, Australian National University, Canberra 0200, Australia Received 20 October 1998 Abstract Musical instruments are often thought of as linear harmonic systems, and a first-order description of their operation can indeed be given on this basis, once we recognise a few inharmonic exceptions such as drums and bells. A closer examination, however, shows that the reality is very different from this. Sustained-tone instruments, such as violins, flutes and trumpets, have resonators that are only approximately harmonic, and their operation and harmonic sound spectrum both rely upon the extreme nonlinearity of their driving mechanisms. Such instruments might be described as ‘essentially nonlinear’. In impulsively excited instruments, such as pianos, guitars, gongs and cymbals, however, the nonlinearity is ‘incidental’, although it may produce striking aural results, including transitions to chaotic behaviour. This paper reviews the basic physics of a wide variety of musical instruments and investigates the role of nonlinearity in their operation. 0034-4885/99/050723+42$59.50 © 1999 IOP Publishing Ltd 723 724 N H Fletcher Contents Page 1. Introduction 725 2. Sustained-tone instruments 726 3. Inharmonicity, nonlinearity and mode-locking 727 4. Bowed-string instruments 731 4.1. Linear harmonic theory 731 4.2. Nonlinear bowed-string generators 733 5. Wind instruments 735 6. Woodwind reed generators 736 7. Brass instruments 741 8. Flutes and organ flue pipes 745 9. Impulsively excited instruments 750 10. -

Music with Heart.Pdf

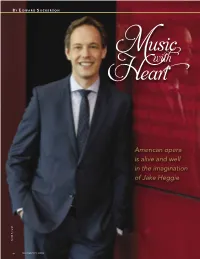

Wonderful Life 2018 insert.qxp_IAWL 2018 11/5/18 8:07 PM Page 1 B Y E DWARD S ECKERSON usic M with Heart American opera is alive and well in the imagination of Jake Heggie LMOND A AREN K 40 SAN FRANCISCO OPERA Wonderful Life 2018 insert.qxp_IAWL 2018 11/5/18 8:07 PM Page 2 n the multifaceted world of music theater, opera has true only to himself and that his unapologetic fondness for and always occupied the higher ground. It’s almost as if love of the American stage at its most lyric would dictate how he the very word has served to elevate the form and would write, in the only way he knew how: tonally, gratefully, gen- willfully set it apart from that branch of the genre where characters erously, from the heart. are wont to speak as well as sing: the musical. But where does Dissenting voices have accused him of not pushing the enve- thatI leave Bizet’s Carmen or Mozart’s Magic Flute? And why is it lope, of rejoicing in the past and not the future, of veering too so hard to accept that music theater comes in a great many forms close to Broadway (as if that were a bad thing) and courting popu- and styles and that through-sung or not, there are stories to be lar appeal. But where Bernstein, it could be argued, spent too told in words and music and more than one way to tell them? Will much precious time quietly seeking the approval of his cutting- there ever be an end to the tedious debate as to whether Stephen edge contemporaries (with even a work like A Quiet Place betray- Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd or Leonard Bernstein’s Candide are ing a certain determination to toughen up his act), Heggie has musicals or operas? Both scores are inherently “operatic” for written only the music he wanted—needed—to write. -

DISTRICT AUDITIONS THURSDAY, JANUARY 21, 2021 the 2020 National Council Finalists Photo: Fay Fox / Met Opera

NATIONAL COUNCIL 2020–21 SEASON ARKANSAS DISTRICT AUDITIONS THURSDAY, JANUARY 21, 2021 The 2020 National Council Finalists photo: fay fox / met opera CAMILLE LABARRE NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS chairman The Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions program cultivates young opera CAROL E. DOMINA singers and assists in the development of their careers. The Auditions are held annually president in 39 districts and 12 regions of the United States, Canada, and Mexico—all administered MELISSA WEGNER by dedicated National Council members and volunteers. Winners of the region auditions executive director advance to compete in the national semifinals. National finalists are then selected and BRADY WALSH compete in the Grand Finals Concert. During the 2020–21 season, the auditions are being administrator held virtually via livestream. Singers compete for prize money and receive feedback from LISETTE OROPESA judges at all levels of the competition. national advisor Many of the world’s greatest singers, among them Lawrence Brownlee, Anthony Roth Costanzo, Renée Fleming, Lisette Oropesa, Eric Owens, and Frederica von Stade, have won National Semifinals the Auditions. More than 100 former auditioners appear appear on the Met roster each season. Sunday, May 9, 2021 The National Council is grateful to its donors for prizes at the national level and to the Tobin Grand Finals Concert Endowment for the Mrs. Edgar Tobin Award, given to each first-place region winner. Sunday, May 16, 2021 Support for this program is generously provided by the Charles H. Dyson National Council The Semifinals and Grand Finals are Audition Program Endowment Fund at the Metropolitan Opera. currently scheduled to take place at the Met. -

Fall/Winter 2017/2018

News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein Fall/Winter 2017/2018 PAM KONER-YOHAI PAM Inside... 2 And Away We Go! 6 Wilbur’s New World 11 LB & the NY Philharmonic 4 Artful Learning 8 Musical Humor in Candide 12 Burton Bernstein 5 LB & Felicia Take a Knee 10 DG Releases 13 In the News FW1718_PFR_art_draft.indd 1 11/22/17 12:58 PM And Away We Go! s this issue makes clear, by Jamie Bernstein and Nézet-Séguin. The following ALeonard Bernstein at 100 Craig Urquhart week, back in Philadelphia, the has shot forth as if out of a orchestra gave performances musical cannon. The concerts, eonard Bernstein at 100 has of West Side Story in concert. recordings, books, educational launched, with Bernstein- To observe the devastation of initiatives, exhibitions, and more like energy. As of this Hurricane Irma and the subse- publishing, there are over quent heartbreak and controversy (on six continents and in all 50 L2,300 events on the centennial surrounding the rescue efforts, states!) are tumbling over each calendar! We don’t have enough Maestro Nézet-Séguin stopped the other like overexcited puppies – space to report on all of them, but orchestra and chorus to let these and it’s not even 2018 yet. here are a few of the highlights. Stephen Sondheim lyrics resonate Thanks to the festivities, less- On September 22, the John F. into the sudden silence: er known Bernstein works are Kennedy Center for the Perfor- Nobody knows in America now finding their moment in the ming Arts officially kicked off Puerto Rico’s in America! sun. -

SF Opera Guild Virtual Event April 28.Pdf

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA GUILD PRESENTS “LIFE. CHANGING. AN EVENING WITH FREDERICA VON STADE & JAKE HEGGIE,” APRIL 28 Frederica von Stade; Jake Heggie (photo: Karen Almond); Gasia Mikaelian SAN FRANCISCO, CA (April 21, 2021) — San Francisco Opera Guild will present a complimentary virtual livestream event Life. Changing. An Evening with Frederica von Stade & Jake Heggie on Wednesday, April 28 at 6 pm Pacific. Mezzo-soprano Frederica von Stade (“Flicka”), American composer Jake Heggie and San Francisco Opera Guild students, alumni and teachers will share inspiring stories and uplifting songs, while celebrating music’s power to change lives. The event includes an intimate Q&A that will give attendees the chance to ask Flicka and Jake questions. KTVU Mornings on 2 news anchor and longtime opera enthusiast Gasia Mikaelian will serve as emcee. Life. Changing. is open to the public; complimentary advance registration required: give.sfoperaguild.com/LifeChanging. 1 Frederica von Stade said: “I love being with my pal, the wonderful Jake Heggie, to celebrate the great efforts of San Francisco Opera Guild in reaching out to the young people of the Bay Area. It means so much to me because I know firsthand of these efforts and have seen the amazing results. I applaud the Guild’s Director of Education Caroline Altman and her work with the Opera Scouts and the amazing team at the Guild. Music changed my life, and I’m excited to celebrate how it changes the lives of our precious young people.” Jake Heggie said: “I'm delighted to join with my great friend Frederica von Stade to spotlight the important, ongoing work in music education made possible by San Francisco Opera Guild. -

01-15-2019 Pelleas Eve.Indd

CLAUDE DEBUSSY pelléas et mélisande conductor Opera in five acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by the composer, adapted from production Sir Jonathan Miller the play by Maurice Maeterlinck set designer Tuesday, January 15, 2019 John Conklin 7:30–11:30 PM costume designer Clare Mitchell First time this season lighting designer Duane Schuler revival stage director Paula Williams The production of Pelléas et Mélisande was made possible by a generous gift from Pierre and Ailene Claeyssens general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 115th Metropolitan Opera performance of CLAUDE DEBUSSY’S pelléas et mélisande conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance gol aud Kyle Ketelsen mélisande Isabel Leonard geneviève Marie-Nicole Lemieux DEBUT arkel Ferruccio Furlanetto pellé as Paul Appleby* yniold This performance A. Jesse Schopflocher is being broadcast live on Metropolitan a shepherd Opera Radio on Jeremy Galyon SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at a physician metopera.org. Paul Corona Tuesday, January 15, 2019, 7:30–11:30PM KAREN ALMOND / MET OPERA Paul Appleby and Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Isabel Leonard in Musical Preparation Derrick Inouye, Carol Isaac, the title roles of Jonathan C. Kelly, and Marie-France Lefebvre Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande Assistant Stage Director Robin Guarino Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Prompter Marie-France Lefebvre Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This performance is made possible in part by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts. -

Romanian Traditional Musical Instruments

GRU-10-P-LP-57-DJ-TR ROMANIAN TRADITIONAL MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS Romania is a European country whose population consists mainly (approx. 90%) of ethnic Romanians, as well as a variety of minorities such as German, Hungarian and Roma (Gypsy) populations. This has resulted in a multicultural environment which includes active ethnic music scenes. Romania also has thriving scenes in the fields of pop music, hip hop, heavy metal and rock and roll. During the first decade of the 21st century some Europop groups, such as Morandi, Akcent, and Yarabi, achieved success abroad. Traditional Romanian folk music remains popular, and some folk musicians have come to national (and even international) fame. ROMANIAN TRADITIONAL MUSIC Folk music is the oldest form of Romanian musical creation, characterized by great vitality; it is the defining source of the cultured musical creation, both religious and lay. Conservation of Romanian folk music has been aided by a large and enduring audience, and by numerous performers who helped propagate and further develop the folk sound. (One of them, Gheorghe Zamfir, is famous throughout the world today, and helped popularize a traditional Romanian folk instrument, the panpipes.) The earliest music was played on various pipes with rhythmical accompaniment later added by a cobza. This style can be still found in Moldavian Carpathian regions of Vrancea and Bucovina and with the Hungarian Csango minority. The Greek historians have recorded that the Dacians played guitars, and priests perform songs with added guitars. The bagpipe was popular from medieval times, as it was in most European countries, but became rare in recent times before a 20th century revival. -

Colorado-Wyoming District Stephen Dilts Karen Mohr Chris Mohr Lynn Harrington Committee

NATIONAL COUNCIL 2020–21 SEASON COLO≤ DO-WYOMING DISTRICT AUDITIONS SUNDAY, JANUARY 31, 2021 The 2020 National Council Finalists photo: fay fox / met opera CAMILLE LABARRE NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS chairman The Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions program cultivates young opera CAROL E. DOMINA singers and assists in the development of their careers. The Auditions are held annually president in 39 districts and 12 regions of the United States, Canada, and Mexico—all administered MELISSA WEGNER by dedicated National Council members and volunteers. Winners of the region auditions executive director advance to compete in the national semifnals. National fnalists are then selected and BRADY WALSH compete in the Grand Finals Concert. During the 2020–21 season, the auditions are being administrator held virtually via livestream. Singers compete for prize money and receive feedback from LISETTE OROPESA judges at all levels of the competition. national advisor Many of the world’s greatest singers, among them Lawrence Brownlee, Anthony Roth Costanzo, Renée Fleming, Lisette Oropesa, Eric Owens, and Frederica von Stade, have won National Semifnals the Auditions. More than 100 former auditioners appear appear on the Met roster each season. Sunday, May 9, 2021 The National Council is grateful to its donors for prizes at the national level and to the Tobin Grand Finals Concert Endowment for the Mrs. Edgar Tobin Award, given to each frst-place region winner. Sunday, May 16, 2021 Support for this program is generously provided by the Charles H. Dyson National Council The Semifnals and Grand Finals are Audition Program Endowment Fund at the Metropolitan Opera. currently scheduled to take place at the Met.